How Sacha Jenkins Rewrote the Culture

Sacha Jenkins left rap journalism bigger than he found it—not by blowing it up, but by handing it back to the crowd and saying, simply, “Your turn.”

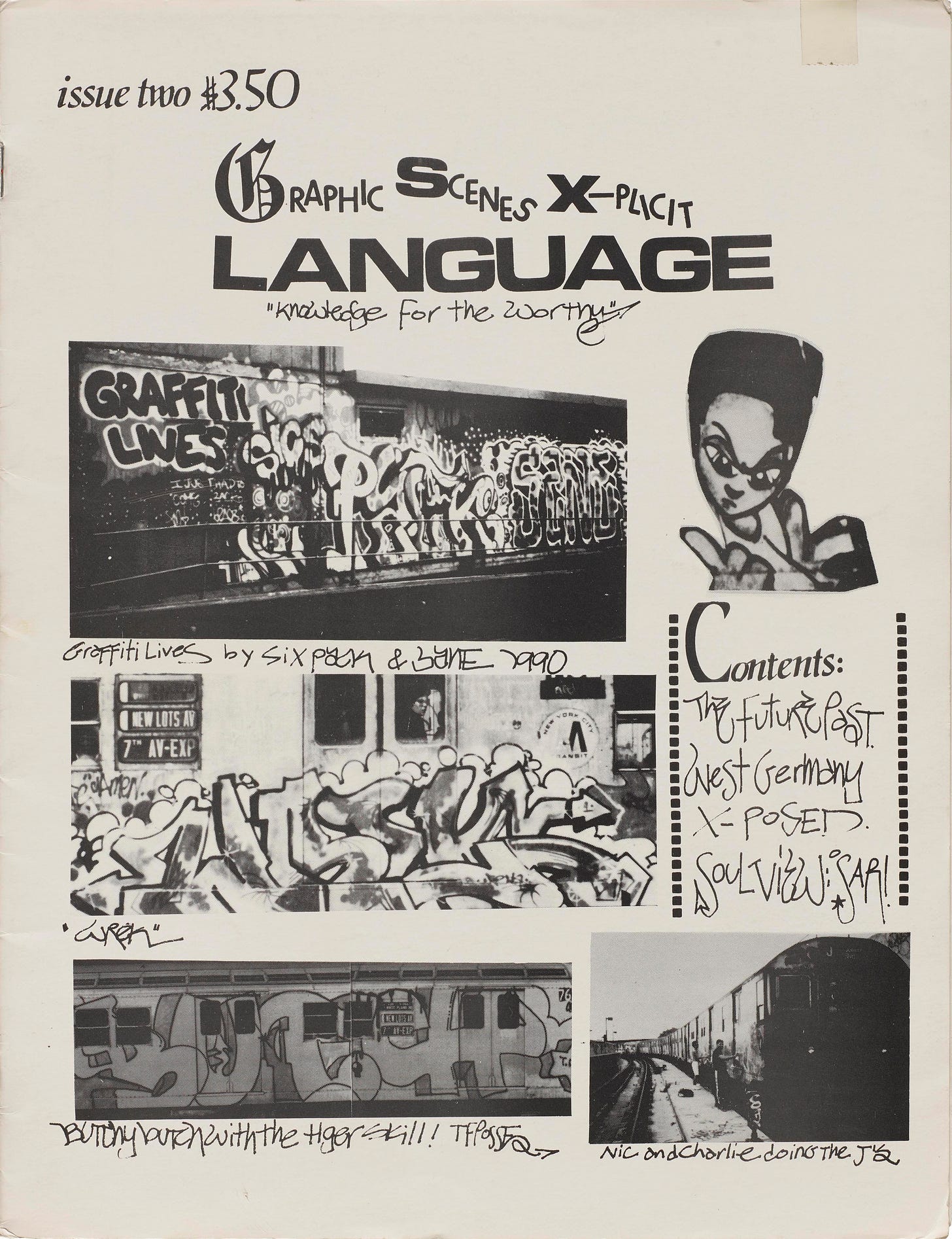

Sacha Jenkins never stopped treating hip-hop as a living, breathing neighborhood. From the moment he Xeroxed the first issue of Graphic Scenes & Xplicit Language in 1988, one of the earliest magazines devoted entirely to graffiti, he insisted that the people who create the culture should also be the ones who write, film, stage dive, and argue about it. Over the next three decades, he channeled that conviction into print, television, film, and music, leaving a latticework of work that feels less like a résumé than a block party flyer: zines and newspapers, a famously fearless magazine, reality-TV experiments, era-defining documentaries, and even a rap-rock concept album. His death on May 23, 2025, at 53, from complications of multiple-system atrophy, closed a chapter, but it did not silence the echo of his mantra: tell our own stories before someone else does.

Born in Philadelphia and raised in Queens, Jenkins sharpened both his eye and pen on subway cars and notebook margins, using graffiti as his first newsroom. Graphic Scenes & Xplicit Language married hand-lettered wildstyle with incisive reporting on the city’s aerosol underground and announced that a teenager could be both critic and participant. By 1992, he and Haji Akhigbade expanded the lens with Beat Down, an all-hip-hop newspaper whose masthead included future XXL editor Elliott Wilson. Their DIY swagger foreshadowed the next leap.

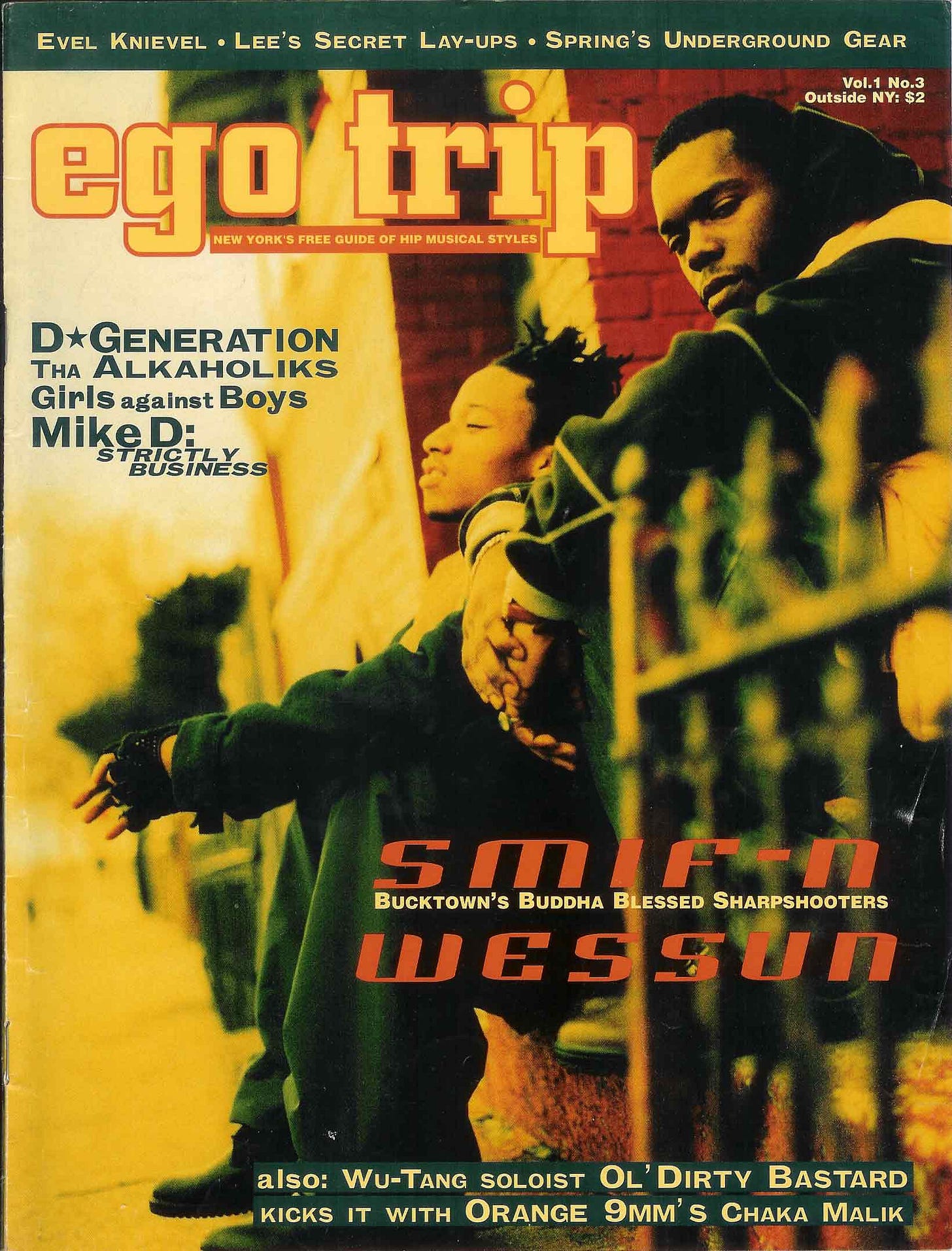

In 1994, Jenkins, Wilson, Chairman Mao, and Brent Rollins launched ego trip, the self-described “arrogant voice of musical truth” that mixed skate-punk, cereal mascots, and rap arcana with razor-sharp cultural commentary. Only thirteen issues hit newsstands, but its influence bled into two cult-classic books—ego trip’s Book of Rap Lists (1999) and Big Book of Racism! (2002)—whose trivia-as-people’s-history approach became standard reference material for a generation of writers and DJs. Even its mischief migrated to television: VH1’s Race-O-Rama, The (White) Rapper Show, and Miss Rap Supreme all bore Jenkins’s imprint, turning hip-hop literacy tests into prime-time theater.

After a stint as Vibe music editor and a writer’s room detour on The Boondocks, Jenkins became chief creative officer at Mass Appeal in 2012, steering the once-dormant magazine into a multimedia studio that treated film, branded content, and long-form journalism as the same beat. His directorial debut, Fresh Dressed (Sundance 2015), chronicled the evolution of hip-hop fashion from sharecropper cotton to Paris runways, while giving tailor-philosophers like Dapper Dan center stage. The film’s success confirmed that Jenkins’s signature—archival deep-cuts, street-corner humor, and unvarnished testimony—could scale to the big screen.

Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men (Showtime, 2019) transformed the traditional behind-the-scenes template into a four-hour oral history, allowing nine founding members to debate destiny, debt, and Shaolin mythology over their own score. Two years later, he pivoted to funk with Bitchin’: The Sound and Fury of Rick James, a raw portrait that juxtaposed punk-funk ecstasy with uncomfortable self-reckonings. In 2022, Jenkins delivered a double-feature: Everything’s Gonna Be All White, a three-part essay on race, rhetoric, and resistance in America, and Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues for Apple TV+, which wove unheard reel-to-reel confessions into a story that complicated the trumpet legend’s public grin. Each project stretched hip-hop’s scope—one day it was Street Etiquette 101, the next it was jazz diplomacy—without abandoning the B-boy’s instinct for first-person truth.

Jenkins never claimed neutrality; he plugged his guitar in. With rapper Murs and Bad Brains bassist Darryl Jenifer he formed the White Mandingos, a rap-rock trio whose 2013 concept album, The Ghetto Is Tryna Kill Me, skewered industry tokenism with hardcore riffage and satirical skits. Interviews found him riffing on Tommy by The Who one minute and Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet the next, underscoring a lifelong refusal to silo Black expression.

Though cameras followed him into boardrooms, Jenkins remained a cipher in corner barbershops, giving young writers résumé tips or poking holes in their arguments before they hit “publish.” Alumni of ego trip remember emailed reading lists and late-night calls that doubled as graduate seminars in subculture theory. Exhibitions like “Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious” at Fotografiska bore his curatorial stamp, proving his eye for photography was as sharp as his ear for 16-bar confession. Even his co-authorship of Eminem’s memoir The Way I Am hinted at a larger impulse: let the artist narrate, you just keep the tape rolling.

Jenkins’s passing triggered a mosaic of eulogies, from graffiti pioneers who first mailed him Polaroids, to documentarians who copied his collage pacing, to fans who learned the difference between breakbeats and breakbeat narratives because of his work. The common thread is agency. He treated culture as a communal turntable that anyone could drop the next record, but you had to know the lineage etched in the dead wax. That ethic lives on in the books students still dog-ear, in documentaries future historians will mine, and in the stubborn idea that journalism is most alive when it sounds like the block it covers. Sacha Jenkins left rap journalism bigger than he found it—not by blowing it up, but by handing it back to the crowd and saying, simply, “Your turn.”

Thank you for what you have given us for decades. We will sincerely miss you.