January 2026 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

From Roc Marciano to Ari Lennox to DJ Harrison, January’s best records asked the same question in different ways. How long can you chase something before it starts chasing you?

When it comes to setting the tone for the year, January has a reputation for being a dumping ground—the month labels burn off contractual obligations before the real release calendar kicks in. This year broke the patternm long silences ended, and label departures paid off. Veterans who’d been doing this for decades delivered work that justified every year of patience, while newcomers showed up sounding like they’d already put in the time. The month’s best records shared a restlessness, a refusal to settle into comfortable shapes. Some ran less than thirty-five minutes and left you wanting more, while others stretched past the hour mark and earned the runtime. Not every swing connected, and at least one album arrived under a cloud its gorgeous arrangements couldn’t quite dispel. But January 2026 made its case early: this year has no interest in easing you in.

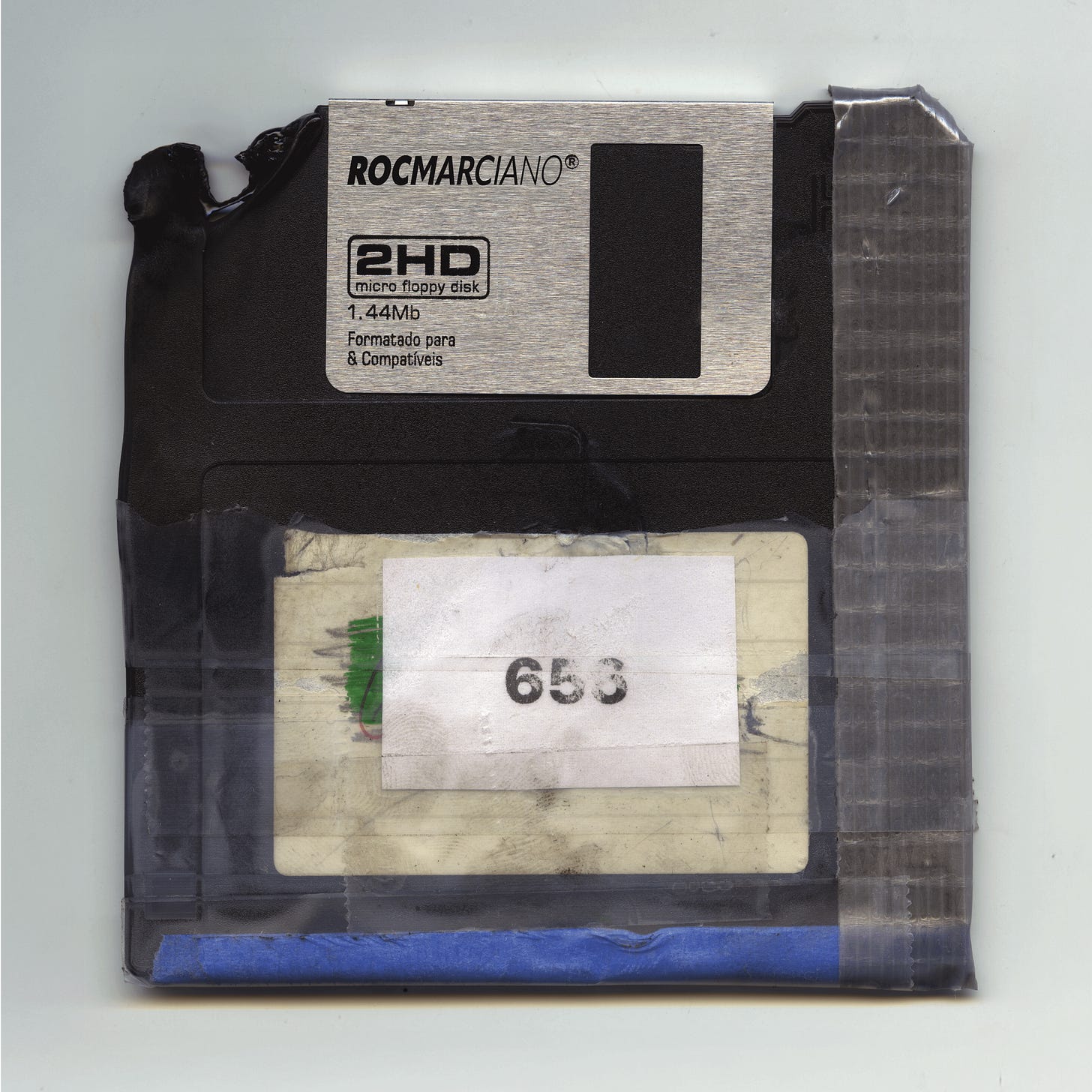

Roc Marciano, 656

656, “neighbor of the beast,” situates Roc Marciano one digit from damnation, which is exactly where he’s been operating for fifteen years now. His new album runs thirty-two minutes, all self-produced under his Quiet Luxury alias, and the brevity feels less like restraint than efficiency. Why procrastinate when the work is this precise? Marciano spent the early 2010s stripping mafioso rap of its major-label sheen, leaving only frayed loops and distant, skeletal drums that sounded like they’d been salvaged from RZA’s flooded basement. Marcberg rewrote the possibilities for underground street rap. Everything that followed (Griselda’s sprawling empire, Mach-Hommy’s cryptic dispatches, the entire luxury grime microgenre) descends from that initial blueprint. With 656, arriving just weeks after the Alchemist-produced Skeleton Key, Marci isn’t expanding his territory. He’s tightening the perimeter.

You know what you’re going to get production-wise, that it’s just as cinematic as the rhymes. “Trick Bag” opens with a slow camera pan, establishing mood before Marci even clears his throat. When he does, the delivery stays that trademark dead-eyed murmur, a man narrating heists and home invasions with the dispassion of someone ordering lunch. His internal rhymes stack and tumble with a density that rewards close listening, but the real pleasure is the temperature. Ice-cold, even when the subject matter should be heated. The album’s central limitation is also its source of power. 656 doesn’t attempt the weight of Reloaded or Rosebudd’s Revenge. It plays like a tightly edited reel rather than a sprawling crime saga. You can run through the whole thing twice in an hour and still want more. For devotees, that’s the point. For newcomers, it’s a concentrated dose of why this 47-year-old from Hempstead remains the reference point for this corner of hip-hop, and why so many imitators, despite flooding the zone, still can’t touch him. — Harry Brown

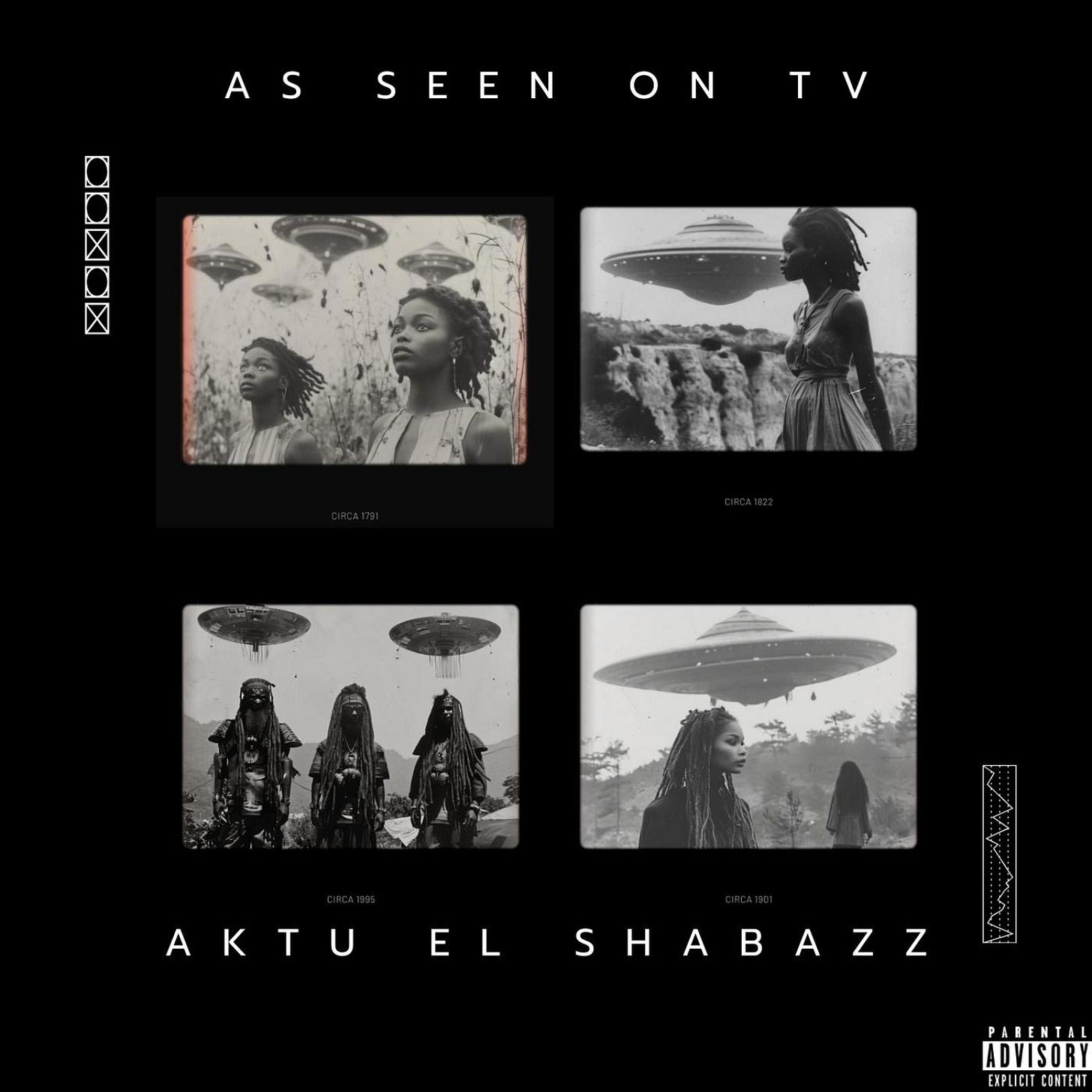

Aktu El Shabazz, As Seen on TV

Brooklyn shaped him; Vancouver kept him. Aktu El Shabazz left New York years ago but never adjusted his internal clock, still rapping in that dense, syllable-packed cadence that East Coast heads perfected in the mid-‘90s. As Seen on TV is his first album since 2022’s K.K.F.W.B., and the title winks at how invisible underground boom-bap has become in the algorithmic age. You won't catch this on a Spotify editorial playlist. You’d have to dig for it the old way, which is exactly why you’re here. Keysha Freshh, a consistent collaborator since his early mixtapes, co-pilots “Storytellin,” the album’s standout. Aktu narrates a neighborhood character study—the bodega owner who knows everyone's vices, the cousin who almost went pro before the knee injury, the corner where deals and friendships both go sideways. He sketches these figures without judgment, just detailed observation, his voice carrying the weariness of who’s watched the same cycles for twenty years. If you miss the era when rappers competed to out-technical each other over dusty loops, As Seen on TV will scratch that itch. If you want evolution, look elsewhere. Aktu made his choice a long time ago. — Koda Lin

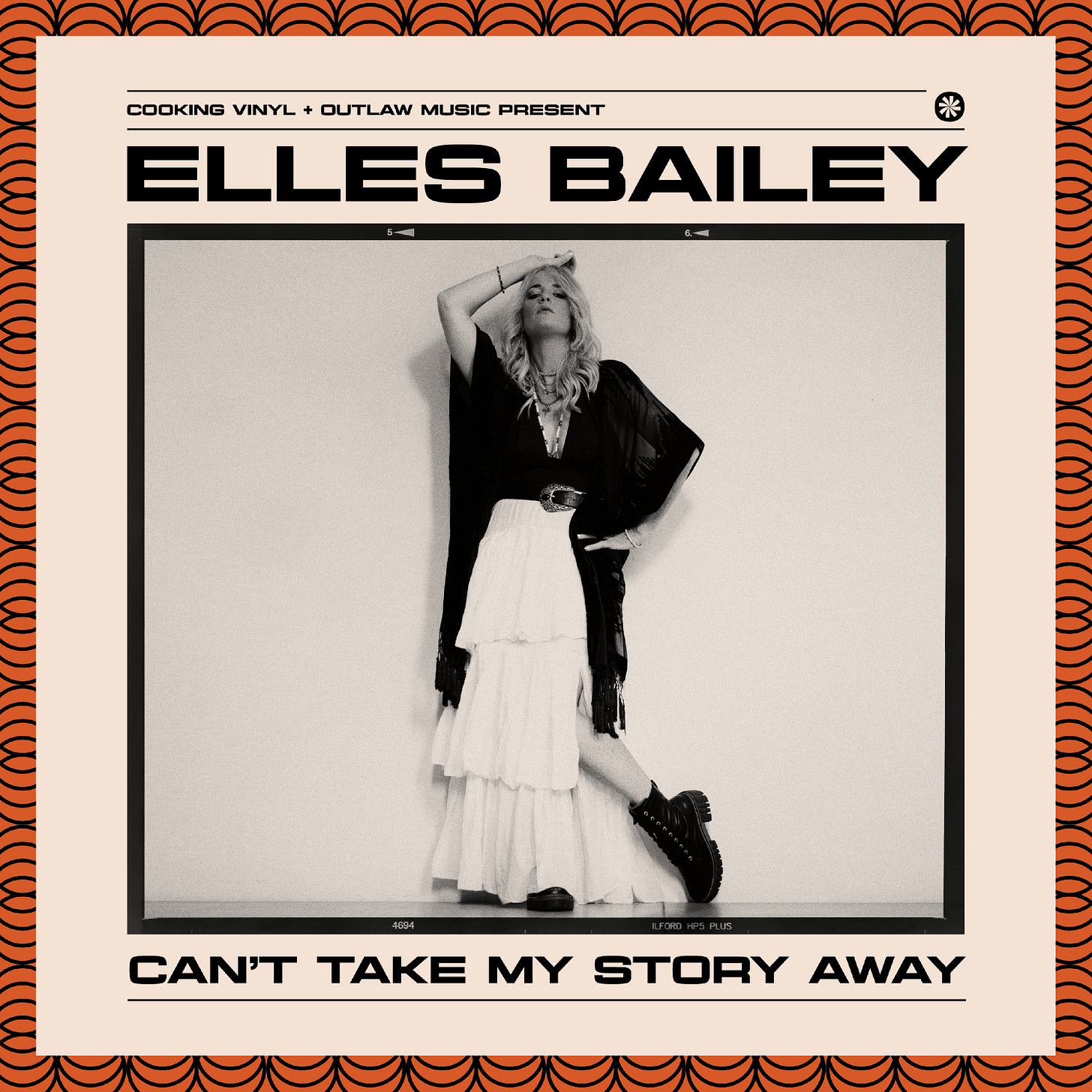

Elles Bailey, Can’t Take My Story Away

British blues-rock has never lacked for practitioners, but Elles Bailey stands apart through sheer vocal force. Her fourth album launches with her whiskey-soaked rasp riding waves of organ and slide guitar, establishing a sound that owes debts to Bonnie Raitt and Beth Hart without simply imitating either. The title track serves as a mission statement. After years of industry nonsense and personal setbacks, no one can strip away the experiences that shaped her.

Helmed by longtime collaborator Dan Mayfield, the sound captures her band’s raw live energy while leaving room for dynamic shifts. “Sunshine City” swaggers with horn-section support. “Crooked Man” strips down to acoustic guitar and vocal harmonies, revealing the folk bones beneath the blues grit. Bailey’s songwriting has sharpened across her discography, and here the lyrics cut without overselling the pain. The album occasionally drifts toward repetition, mid-tempo shuffles dominating the second half. But Bailey’s voice papers over the structural sameness. She has the range to whisper or wail depending on what the song requires, and she makes those choices deliberately rather than defaulting to histrionics. — Charlotte Rochel

SAULT, Chapter 1

The mystery surrounding SAULT has long since evaporated. We know producer Inflo helms the collective, that his wife Cleo Sol provides many of the vocals, that their prolific run since 2019 has produced some of the decade’s most gorgeous soul music. What’s still opaque is the intention. Why release another album now, particularly after the messy public fallout with Little Simz over an unpaid £1.7 million loan? Chapter 1 arrives shadowed by that controversy, its title suggesting fresh starts while the circumstances suggest anything but. Set that aside, if you can, and the music holds up. Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Janet Jackson’s architects, contribute to several tracks, and you can hear their influence in the slick, machine-tooled grooves beneath the funk and blues textures. “God, Protect Me From My Enemies” surges with orchestral grandeur, 27 musicians credited on a single song. Cleo Sol glides between the string arrangements on “Lord Have Mercy” with the effortlessness that’s defined her work, her voice adding depth even when the lyrics veer toward motivational-poster territory. Consistently gorgeous, reliably surprising in their stylistic pivots, and delivered without warning. Whether Inflo’s offstage behavior complicates that pleasure is a question each one has to answer for themselves. The music won’t help you decide. It simply exists, pristine and unbothered, regardless of the context that created it. — Phil

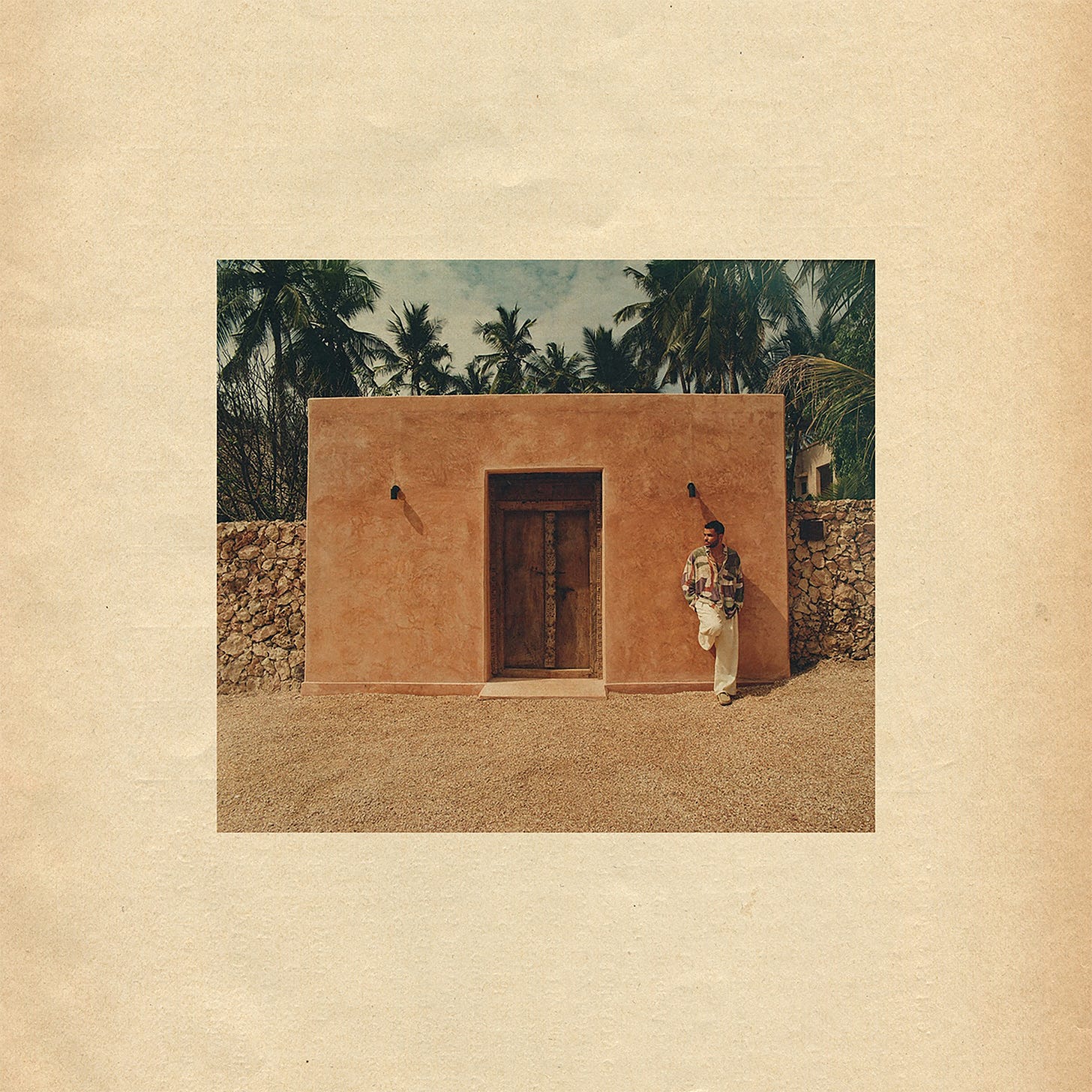

Ady Suleiman, Chasing

After a major-label stint that produced one album and considerable frustration, Ady Suleiman returned to independence and found his footing. Chasing is his third overall solo project (counting the Thoughts & Moments Vol. 1 Mixtape) and his most cohesive. British soul that bridges Sam Cooke and contemporary London club culture. “Better Days” kicks off with a bass-heavy groove and Suleiman’s voice floating above it, promising hope without ignoring present difficulty. “Waiting” slows the tempo to ballad territory, showcasing the range that’s drawn comparisons to Michael Kiwanuka and James Blake. The production throughout radiates warmth. Live instrumentation, minimal auto-tune, room ambience that suggests intimacy rather than sterility. He writes about specific relationships and recognizable emotions rather than retreating into abstraction. “Chasing” itself examines the exhaustion of pursuing something that keeps receding, and the sentiment lands. For an artist who once seemed poised for crossover success, this independent path suits him better. Less polished, more personal. — Alexandria Elise

Stu Bangas & Wordsworth, Chemistry

Wordsworth wrote his college papers in rhyme. That biographical detail, frequently cited in profiles from the late ‘90s, still governs his approach. The Brooklyn MC thinks in verse, building sentences that double back on themselves, internal rhymes tucked into corners where casual listeners might miss them. On Chemistry, his second album with Boston producer Stu Bangas, that technical obsession meets a perfect foil. Bangas builds beats that hit like a fist through drywall—raw, direct, unconcerned with subtlety. The duo connected in 2024 on 2 Kings, a solid collaborative debut that proved they belonged in the same room. Chemistry tightens what worked before. “The Realtor” opens with Wordsworth parsing the predatory economics of gentrification, his realtor narrator both villain and victim, moving families out of neighborhoods they built while the commission checks keep cashing. “Strangers” follows, Bangas dialing back the drums to let a mournful loop breathe while Wordsworth catalogues relationships gone cold—old friends who became acquaintances, lovers who became cautionary tales. Ruste Juxx trades verses on "The Only Sin," both MCs grappling with the cost of staying principled in an industry that rewards compromise. Masta Ace reunites with Wordsworth on "People in the Neighborhood," their chemistry forged through eMC, the supergroup they share with Punchline and Stricklin. Apathy and Punchline mob through "I Was Raised," a posse cut that briefly summons the Lyricist Lounge energy where Wordsworth first made his name. — Quinn Baptiste

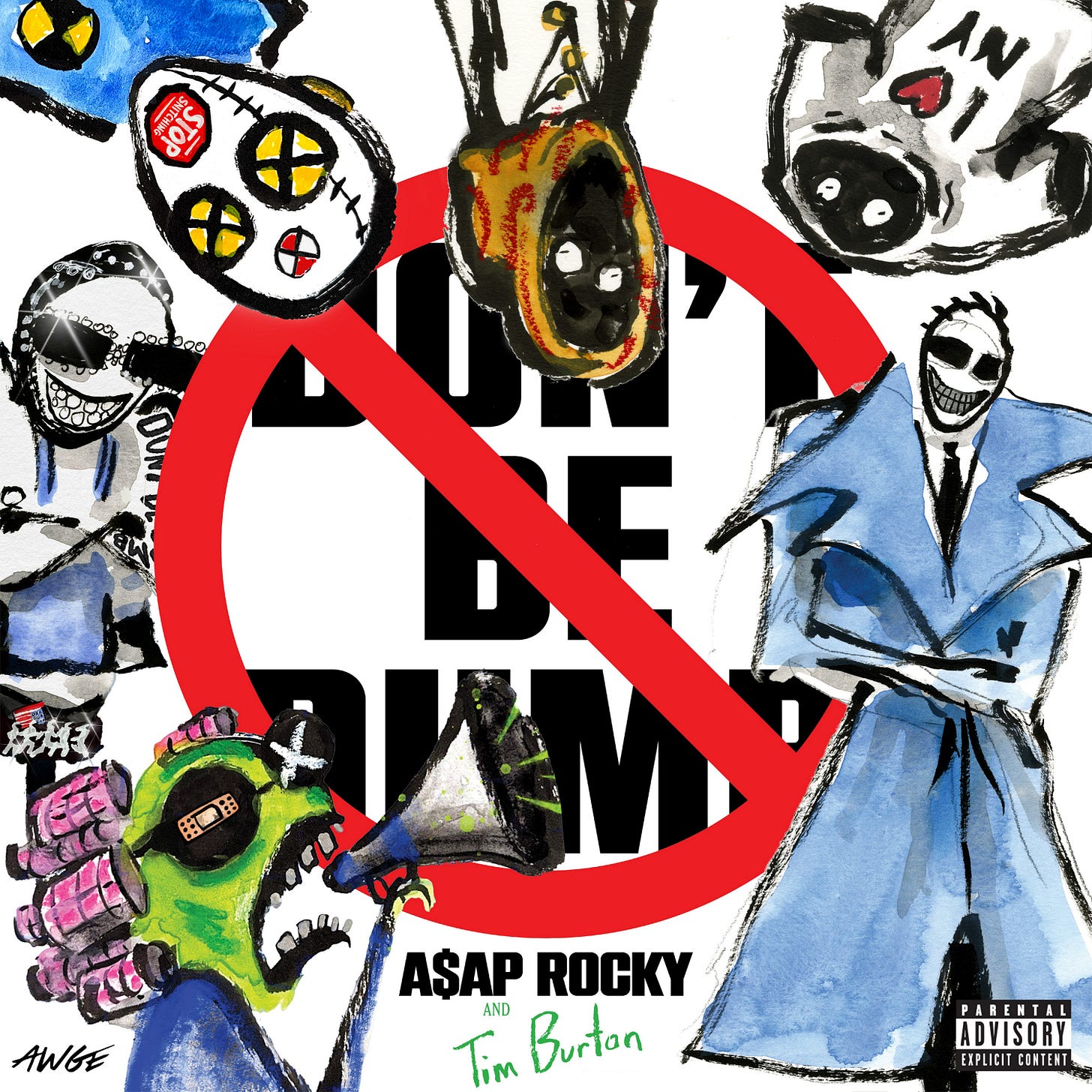

A$AP Rocky, Don’t Be Dumb

Eight years. That’s how long A$AP Rocky waited to follow Testing, a divisive experiment that alienated casual fans and fascinated obsessives. In that gap, he acted in A24 films, co-chaired the Met Gala, started a family with Rihanna, and watched the rap landscape shift beneath him multiple times. The question hovering over Don’t Be Dumb wasn’t whether Rocky could still rap. It was whether he still wanted to, and if so, what he’d have to say about the world he’d semi-abandoned. It’s a wildly ambitious creative swing, and Rocky mostly connects. Where else would you find Westside Gunn ad-libbing gun sounds over Damon Albarn harmonies, as on “Whiskey (Release Me)”? Or Jessica Pratt’s bewitching psych-pop colliding with apocalypse bars from will.i.am on “The End”? Rocky told The New York Times this record represents “what 2011 Rocky would be making in 2026,” and that paradox, nostalgia projected forward, defines the listening experience. The Jordan Patrick and Loukeman beats on “Don’t Be Dumb / Trip Baby” recall Live.Love.A$AP, but the execution sounds contemporary, the mix wider and stranger. After so long away, Don’t Be Dumb isn’t the cultural reset Rocky might have hoped for. But it proves he hasn’t lost the thread. The pretty MFer still knows how to throw a party. — Zachary Penn

IDK, e.t.d.s. A Mixtape by .idk.

The producer credits alone could carry a review. KAYTRANADA, No I.D., Madlib, Conductor Williams. Add features from Pusha T, RZA, Black Thought, and a posthumous DMX verse (the first officially approved by the estate since his death), and e.t.d.s. looks like a hall-of-fame compilation for hip-hop elitists. IDK (born Jason Mills) has spent years orbiting the mainstream, acclaimed but never quite breaking through, and this project represents his most direct attempt to consolidate that respect into something undeniable. The conceit is 90s/2000s mixtape culture. Urgent, raw, built for street circulation rather than streaming algorithms. IDK draws from his personal experience with incarceration to fuel the narrative, and the urgency alights. “SCARY MERRi,” produced by Conductor Williams, hits with dizzy, sinister energy, the kind of song you brace yourself for rather than simply enjoy. “S.T.F.” pairs KAYTRANADA’s bounce with DMX’s gravelly snarl, and hearing X’s voice on new production carries genuine emotional weight. IDK persists as a strange figure in contemporary rap. Too cerebral for street playlists, too street for backpack purists, too ambitious to settle for cult-favorite status. e.t.d.s. won’t change that positioning, but it might be the definitive statement of what makes him singular. — Nehemiah

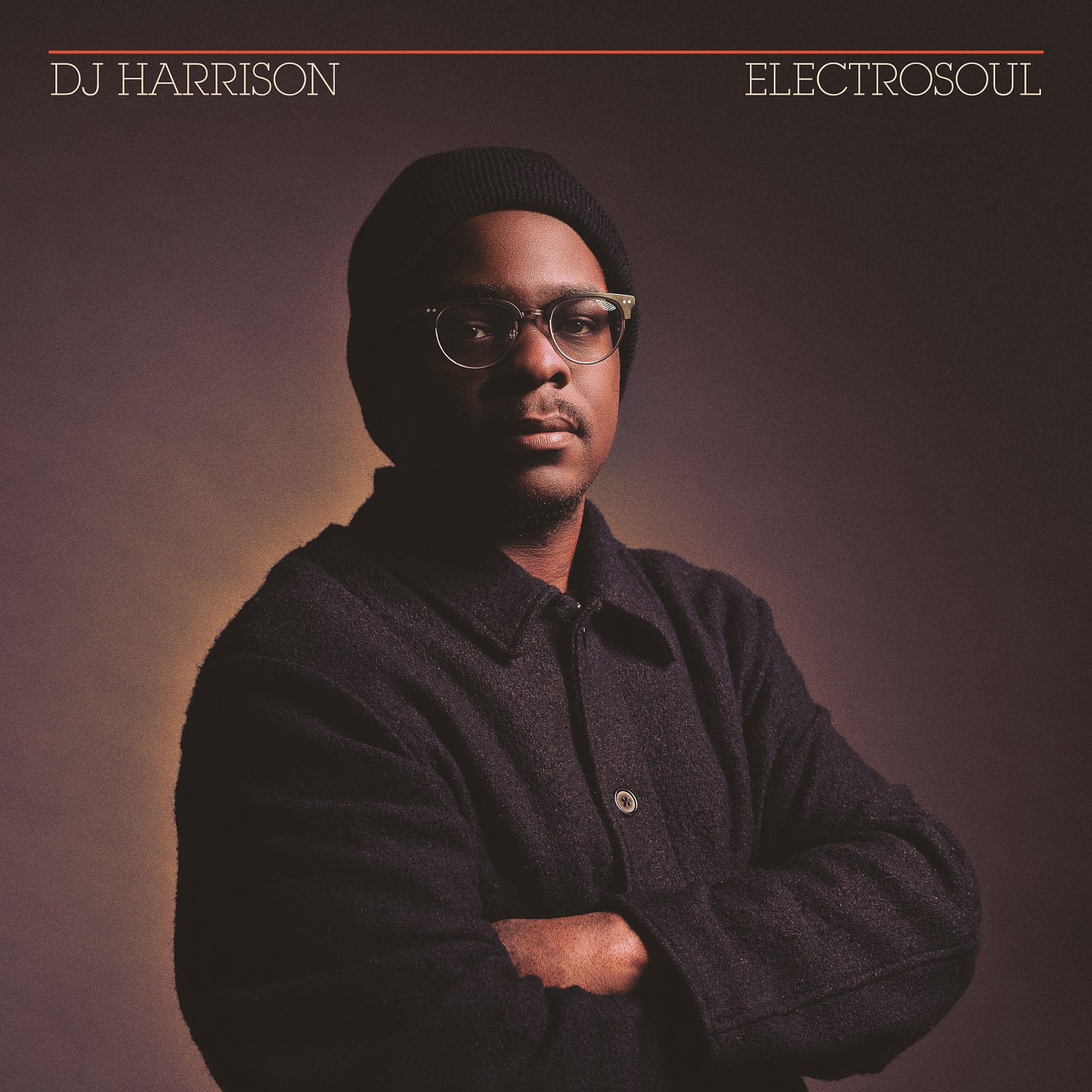

DJ Harrison, ElectroSoul

A health scare changed everything. When Devonne Harris, the multi-instrumentalist behind DJ Harrison, was hospitalized in 2024, a reaction to medication kept him there far longer than expected. All he could think about was the music he’d make when he got home. The product is ElectroSoul, his most collaborative record yet, featuring Yazmin Lacey, Yaya Bey, Fly Anakin, Pink Siifu, Kiefer, Angélica Garcia, and multiple members of his band Butcher Brown. Harrison’s previous Stones Throw albums, Tales from the Old Dominion and Shades of Yesterday, established his dusty, analog approach to funk and jazz. ElectroSoul expands the palette without abandoning the foundation. “Stay Ready” pairs Yaya Bey’s honeyed vocals with caramel-smooth production that nods toward future soul without losing the warmth of Harrison’s live instrumentation. “It’s All Love” finds Yazmin Lacey gliding over a groove that could have fit on a Roy Ayers session. Pink Siifu shows up on “Y’all Good?” to add his signature croak, and the combination of his roughness with Harrison’s polish works better than it should. Richmond, Virginia doesn’t often get positioned as a soul-music capital, but Harrison has been quietly building that case for years. ElectroSoul is his strongest argument yet. — Brandon O’Sullivan

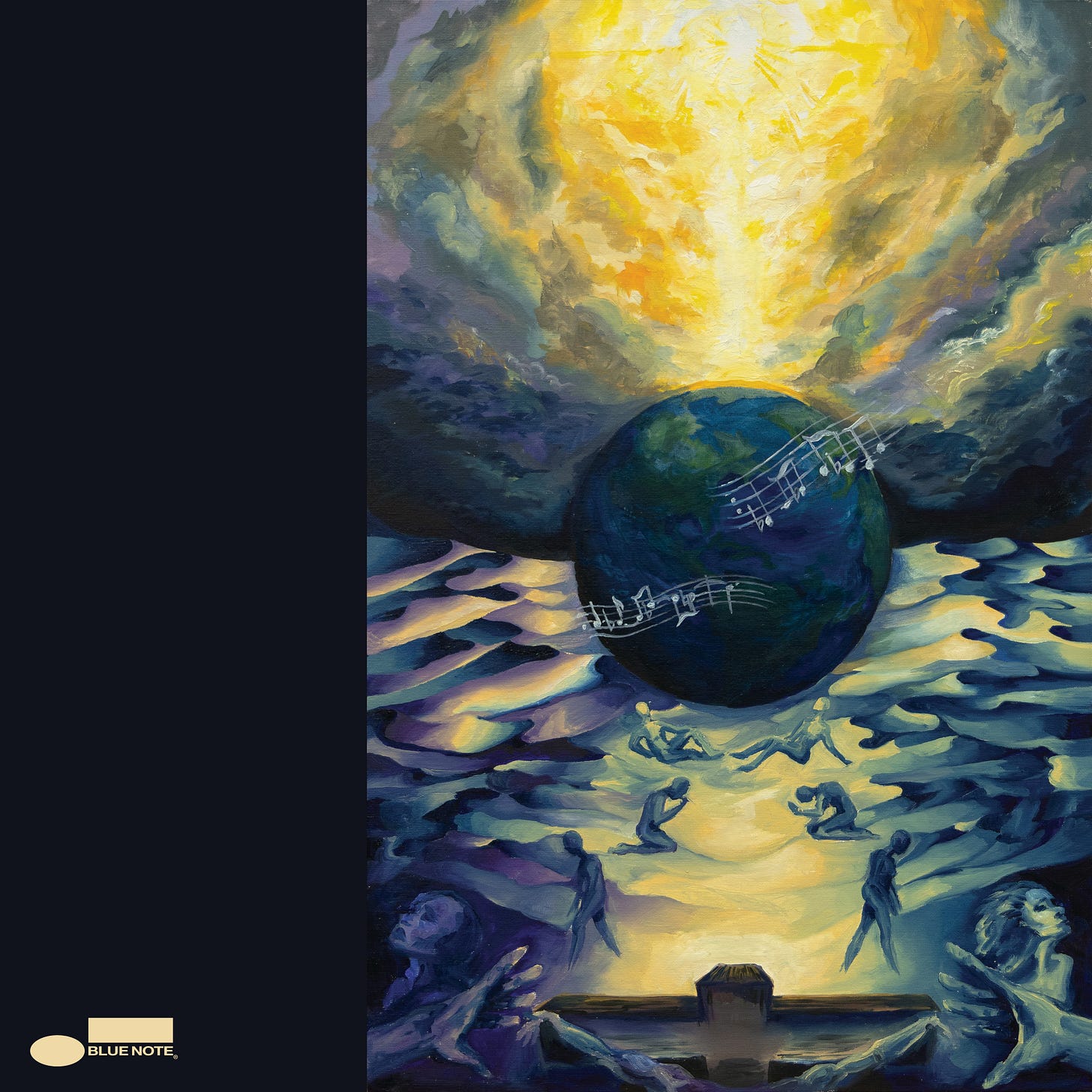

Joel Ross, Gospel Music

Joel Ross plays vibraphone with two mallets instead of four, a choice he’s described as a deliberate handicap. Most contemporary vibraphonists use four to dictate harmony; Ross prefers the constraint, approaching the instrument’s cold metal bars as a challenge, not a canvas. That stubbornness defines Gospel Music, his fifth Blue Note album and his most personal statement yet. The record follows the arc of biblical narrative. Creation, fall, salvation. Each composition corresponds to a specific text Ross includes in the liner notes, though you don’t need the scripture to feel the weight. “Wisdom Is Eternal (For Barry Harris)” memorializes the late bebop pianist who taught Ross to hear harmony as emotion. “Trinity (Father, Son and Holy Spirit)” stretches past seven minutes, the expanded sextet (Josh Johnson on alto, María Grand on tenor, Jeremy Corren on piano, Kanoa Mendenhall on bass, Jeremy Dutton on drums) moving through zones of tension and release without ever settling into groove for its own sake. Ross grew up in Chicago absorbing gospel through osmosis. Black church music seeped into his ears whether he sought it out or not. But he gravitated toward jazz pedagogy, studying under Stefon Harris at the Brubeck Institute before joining Blue Note’s roster of young lions. Gospel Music reconciles those two inheritances. — LeMarcus

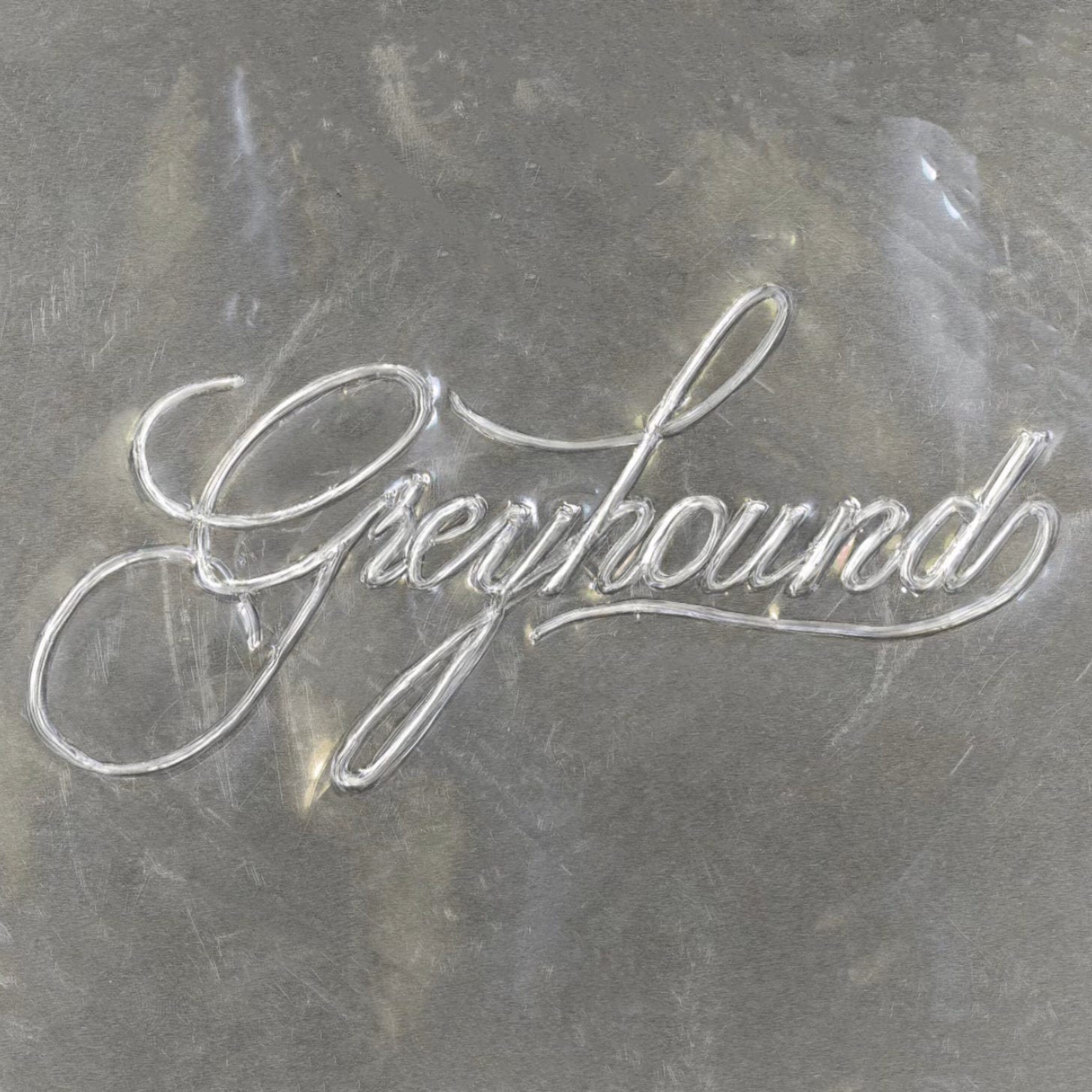

Katie Tupper, Greyhound

The title demands explanation, and Tupper supplies one. Racing greyhounds chase mechanical rabbits that are designed to stay just out of reach. Speed up, and the decoy speeds up too. The dogs think they’re pursuing something attainable, but the game is rigged. “I am often both the Greyhound and the decoy,” she’s said of her relationships, “Chasing something unreachable and being the thing that cannot be caught.” That duality shapes her debut, a collection of folksy soul from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Producers Justice Der and Felix Fox, both members of her touring band, craft a sound that straddles British neo-soul and after-midnight intimacy. Tupper’s smoky alto carries the songs, but the arrangements inject life into the songs. Strings swell without overwhelming, drums and bass offer gentle propulsion, and the occasional electronic flourish adds texture without cluttering the mix. “Disappear” unfurls with layered vocals and slow piano chords, Tupper singing about a relationship she couldn’t escape quickly enough. “I can’t be your woman, I can’t even be your friend.” Jordan Rakei and Rachel Bobbitt add harmonies to the album version, but the song’s power comes from its stillness, the way Tupper lets the sentiment sit rather than overselling it. “Sick to My Stomach” twists its title into something more complicated. “Sick to my stomach/But in a good way.” She knows what she’s doing with language, bending clichés until they reveal new meanings. — Imani Raven

By Storm, My Ghosts Go Ghost

Jordan Groggs died in June 2020, three months into a pandemic that made grief feel universal and impossibly private. He was 32. His bandmates in Injury Reserve, rapper RiTchie with a T and producer Parker Corey, finished the album they’d been making together and released it as By the Time I Get to Phoenix, naming it after an Isaac Hayes cover Groggs had championed. Then they went quiet. When they resurfaced in 2023, they’d renamed themselves By Storm, a nod to that album’s final track and a signal that continuation would require reinvention. My Ghosts Go Ghost is their first full-length under the new name, and it refuses the easy narrative of healing. billy woods appears on “Best Interest,” lending his gnarled presence to a track that sounds like industrial machinery breaking down in slow motion. “Dead Weight” and “Grapefruit” careen through tempos and textures that recall the glitchy, abrasive production Corey pioneered on Phoenix but pushed further into abstraction. RiTchie’s delivery has always run cooler than Groggs’s loose-limbed charisma; here, that coolness reads as self-protection, a man circling the perimeter of his own loss rather than diving straight in. The duo developed this material through a process that mirrors how Phoenix came together. RiTchie moving through the wreckage without pretending he’s reached the other side. Groggs’s absence is the album's gravitational center, bending everything around it. — Brandon O’Sullivan

BBE Music, Naive Melodies

Talking Heads tribute compilations risk embarrassment more than most. The originals are so strange and perfect that covers can only illuminate the distance between intent and execution. Naive Melodies (named after the subtitle of “This Must Be the Place”) assembles an eclectic roster of producers and vocalists to reimagine the catalog, and the material is a new surprise. BBE recruited artists who understand the source material’s tension between nervous energy and transcendent joy. Nosaj Thing’s take on “Once in a Lifetime” retains the existential unease while adding skittering electronics. Yazmin Lacey brings warmth to “Naïve Melody” without defanging its restless pulse. Other contributions vary in success. As a label exercise, Naive Melodies reveals BBE’s curatorial strengths. Knowing which artists to match with which material, understanding that tribute albums succeed through interpretation. — Priya Okafor

Grupo Um, Nineteen Seventy Seven

Nearly fifty years sat between recording and release. In 1977, brothers Lelo and Zé Eduardo Nazario gathered with bassist Zeca Assumpção, saxophonist Roberto Sion, and percussionist Carlinhos Gonçalves at Rogério Duprat’s Vice-Versa Studios in São Paulo. Brazil’s military dictatorship had reached its most repressive phase; censors controlled radio and television, and many artists had fled the country. Grupo Um stayed, making music that fused avant-garde jazz with Afro-Brazilian rhythm in a small studio with a four-channel tape machine and no overdubs. Everything went straight to tape. The band had grown out of Hermeto Pascoal’s legendary mid-70s collective, and you can hear that lineage in the way they handle rhythm as a living organism. Far Out unearthed the tapes for the band’s 50th anniversary, two years after finally releasing Starting Point, recorded in 1975 and similarly shelved for half a century. Where that debut caught a trio finding its footing, Nineteen Seventy Seven documents an expanded quintet confident enough to push into riskier territory. The Parasound electronic reverb units audible on the soprano sax and percussion give the recording an underwater shimmer, as if the music were reaching through time to find us. The music kept waiting. Now it’s here, this is what freedom sounded like when freedom was dangerous. — Yara Blake

The James Hunter Six, Off the Fence

Forty years since his recording debut, James Hunter endures as the United Kingdom’s best-kept soul secret. After thirteen albums with Daptone Records, he’s moved to Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound, though the transition is less a break than a continuation. Daptone co-founder Gabriel Roth produced the record, and the sound (mono-adjacent, horn-driven, indebted equally to 60s R&B and British pub-rock resilience) picks up exactly where With Love left off. The headline attraction is Van Morrison, singing words Hunter wrote for the first time. “Ain’t That a Trip” is a jump-blues blaster where Morrison sounds almost like Benny Spellman, trading verses with Hunter’s leather-throated growl. The two have collaborated since the early 90s, when Hunter appeared on Morrison’s A Night in San Francisco, but this registers as a full-circle moment. The student getting the master to finally sing one of his songs. Beyond that cameo, at 66, Hunter has nothing left to prove. His band (Myles Weeks on upright bass, Rudy Albin Petschauer on drums, Andrew Kingslow on keys, Michael Buckley and Drew Vanderwinckel on horns) plays with the locked-in ease of musicians who’ve been doing this together for decades. Not nostalgic, just uninterested in proving it belongs to any particular era. — Kendra Vale

Ari Lennox, Vacancy

Six months after leaving Dreamville amid public frustration over the label’s handling of her career, Ari Lennox arrives with her most confident album yet. Vacancy took three years and multiple cities (Atlanta, Los Angeles, Miami) to complete. Executive producer Elite shaped the final sessions, and Lennox co-wrote every track, a detail worth explaining given how rarely R&B singers of her profile maintain that level of authorial control. The opener “Mobbin’ in DC” announces her DMV roots immediately, Elite’s production warm and unhurried beneath Lennox’s sighing alto. But the album’s anchor is the title track, reuniting her with Jermaine Dupri and Bryan-Michael Cox, the duo behind her platinum single “Pressure.” Their chemistry holds. The interpolation of the Flamingos’ “I Only Have Eyes for You” on “Under the Moon,” that iconic “sha bop sha bop,” cruises on a smoky bassline while Lennox howls about a lover who might be a literal werewolf. It’s charming rather than campy, which is harder to pull off than it sounds. Lennox excels at balancing classy and freaky without tipping into either extreme. “Pretzel” (as in, she wants to be twisted up like one) makes the case. So does “Highkey,” where she staccato-chants “let me be your freaky lullaby” over fluttering vocal runs. She’s reaching backward, but the references don’t overwhelm her own personality. Lennox seems to be finally having fun, as you can tell from her vocals. And she’s using every inch of it. — Jamila W.

cropscropscrops & Vaygrnt, We’ve Been After Each Other

Isolation stops feeling useful eventually. It starts changing the shape of your surroundings. We’ve Been After Each Other, the second full-length collaboration between Ohio-born, Montreal-based rapper cropscropscrops and producer Vaygrnt, lives in that transition. Abstract hip-hop rarely sounds this domestic. ELUCID guests on “Anatomy Angels,” bringing his own damaged eloquence to a track about bodies and their betrayals. His verse slots perfectly into the album’s architecture; he’s been making records about precarity and survival for over a decade with Armand Hammer, and cropscropscrops operates in adjacent territory. Jaythehomie and Edaya contribute to “English Ivy” and “Silent Auction,” respectively, each voice adding texture without disrupting the album’s central loneliness. “We Used to Dance” is the emotional center, cropscropscrops recounting a relationship through physical motion on how they used to move together, how they stopped, how the absence of that movement left a shape he stumbles into still. A man documenting his own erosion, hoping the document itself counts for something. — Nehemiah

The Sha La Das, Your Picture

The Dunham brothers (Billy, Thomas, Max, and Liam) grew up with parents who worked at Daptone, absorbing the label’s reverence for vintage soul from childhood. Their debut single arrived when the eldest was barely out of high school. Your Picture is their second album, and the generational transmission has clearly succeeded. These songs sound lifted from a 1965 jukebox, complete with doo-wop harmonies, upright bass, and recording techniques that predate most of the band members’ births. “Your Picture” (the title track) illustrates their approach with their lyrics about longing that could have been written for Frankie Lymon. “Counting Stars” slows to a waltz tempo, the brothers’ voices blending with sibling precision. The production, handled in-house at Daptone’s Brooklyn studio, preserves the label’s signature analog warmth without tipping into parody. These are young musicians genuinely excited by forms that were old before their grandparents met. The sincerity sells it. Retro-soul can curdle into nostalgia tourism. The Sha La Das avoid that trap through commitment and vocal chemistry that no amount of technical proficiency can fake. — Tori Hammond

Guys I just discovered you and your amazing work. If you might need some help, I'm here!