Jesse Jackson Made “I Am Somebody” a Daily Saying

Jesse handed dignity to kids and workers in these words. Say it once, and you can hear the crowd answer back.

Somebody opens the call. The room is tight, shoulders touching, the air thick with breath and floorboard heat. A voice pitches high and deliberate from the front, each syllable spaced so a child can follow it: I am—somebody! And the room returns it. Not a whisper. Not a murmur. A holler, chests up, spines pulling straight as the sentence fills the space between bodies. People who walked in with their eyes on the carpet now fix them forward. The phrase does physical work on them. It stiffens a jaw, lifts a chin, pushes a pair of lungs wider open. In church basements across Chicago’s South Side, in school gymnasiums where the bleachers had been folded against the wall, in union halls that stank of old coffee and radiator dust, this five-word sentence traveled through rooms and rearranged the people standing in them.

The man behind that sentence was born in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1941, to a sixteen-year-old mother who raised him under Jim Crow. Jesse Louis Jackson spent his childhood walking past the whites-only school on his route to an inferior one, absorbing the daily mechanics of exclusion. Tall and loud and restless, he earned a football scholarship, transferred to North Carolina A&T, and by 1965 had left Chicago Theological Seminary unfinished because Selma, Alabama, needed bodies on the ground. Within months he had joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and driven himself into Martin Luther King Jr.’s orbit by sheer persistence. Andrew Young, who knew both men well, explained why King tolerated Jackson’s relentless petitioning for attention. King recognized that Jackson “compulsively needs attention” the way a fatherless child would, and so he held space for that hunger rather than banishing it.

King was pivoting the SCLC’s attention toward economic life when Jackson proved most useful. The program was called Operation Breadbasket, and its premise was blunt. If a company collected money from Black neighborhoods but refused to hire Black workers, Black customers would stop buying. Jackson helmed the Chicago franchise of Breadbasket starting in 1966, and his first target was a dairy that distributed to more than a hundred stores in Black areas. When the company refused to open its employment records, Jackson enlisted pastors, and their congregations emptied the dairy’s shelves within days. The company pledged to reserve twenty percent of its positions for Black inner-city residents. Next came the High-Low Foods grocery chain, which buckled after ten days of picketers outside its storefronts and committed to hiring 183 Black employees across every level from delivery to management. Jackson treated each capitulation as a tutorial. Gratitude from these corporations did not interest him. He wanted them to understand a transaction: respect the dollar, respect the person spending it.

This was Chicago in the late 1960s, a sprawling, bitter-cold city where six million Black southerners had migrated only to discover that discrimination in the North wore suits instead of hoods but operated with identical purpose. Richard J. Daley operated the tightest political machine in postwar America, and his control of Black wards depended on their compliance. Jackson threatened that arrangement simply by existing. Without an appointment, he showed up at Daley’s office on a regular schedule. When the mayor agreed to meet, Jackson walked out and told reporters what they discussed. When Daley refused, Jackson held a press conference outside the glass doors and told reporters what he would have said. The mayor had never absorbed that kind of pressure from a single individual, and his response was to plant an undercover officer in Jackson’s entourage disguised as a bodyguard, charged with feeding intelligence back to City Hall.

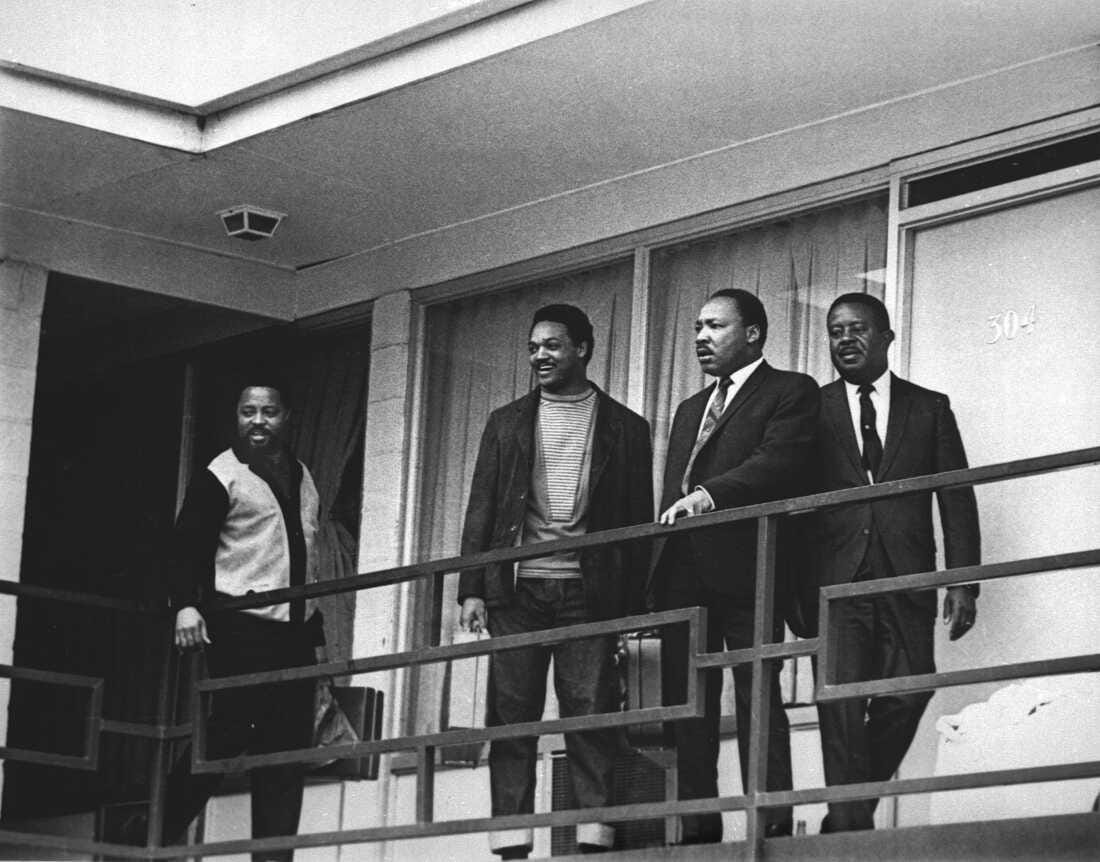

After King was murdered at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis on April 4, 1968, Jackson spent three years grinding against the SCLC’s remaining leadership, who distrusted his ambition and suspected him of co-opting King’s name. They suspended him in 1971 after discovering he had incorporated the lucrative Black Expo festival under his own name rather than the SCLC’s. Jackson resigned, gathered five thousand followers at the Metropolitan Theatre on the South Side, and declared that “a new movement is about to be born.” People United to Serve Humanity had the same DNA as Breadbasket: economic empowerment through organized pressure. But PUSH also had a board stacked with the country’s Black elite, including Quincy Jones, Berry Gordy, and Manhattan borough president Percy Sutton. Jackson could pack a Saturday morning meeting hall with thousands of ordinary citizens and then have dinner with the most recognized names in Black America. He operated as preacher, negotiator, and celebrity at once, and that combination rattled everyone who assumed those roles belonged in separate rooms.

PUSH’s Saturday broadcasts on Chicago radio turned “I am somebody” into a weekly ritual. Listeners across the city chanted along as Jackson intoned the verses. I may be poor, but I am—somebody! I may be young, but I am—somebody! I may be on welfare, but I am—somebody! Each line attached the declaration to a specific condition. Poverty was named. Youth was named. Welfare dependence was named. And each condition was overruled by the same verdict. The chant did not ask anyone to pretend their circumstances away. It demanded they refuse to let those circumstances define their worth. Surrounded by a mixed group of children, Jackson recited the same words on Sesame Street, planting them in the mouths of kids who were still learning to tie their shoes.

And the chant carried economic teeth. In 1972, General Foods and Schlitz Breweries signed what PUSH called “covenants” with Black communities. The General Foods agreement alone required the company to create 360 jobs for Black workers and other minorities across every department, direct twenty million dollars of its insurance volume to Black-owned insurance companies, retain Black law firms, employ Black physicians and their paramedical staff, use Black-authorized automobile dealers, deposit an additional five hundred thousand dollars in Black-owned banks, hire Black contractors for all plant construction and renovation, and increase its advertising in Black print media while strengthening its relationship with Black-owned advertising agencies. That single covenant funneled approximately sixty-five million dollars into Black communities. When Coca-Cola balked at a similar arrangement, Jackson reminded its executives that their spokesman, Bill Cosby, was a PUSH supporter. Coca-Cola signed. Quaker Oats, 7UP, and Avon followed. The Wall Street Journal reported that white corporate leaders privately regarded Jackson as “a superb negotiator” who knew “exactly when to get tough, when to pull back, and when to bring God into the discussion.” Others called him and his team “the moral Mafia.” Jackson accepted both descriptions.

This was what “I am somebody” sounded like when it left the call-and-response circle and walked into a boardroom. The chant was not mood. It was a set of demands backed by organized purchasing power, picket lines, and the threat of Sunday sermons aimed directly at a corporation’s quarterly revenue.

Jackson’s collision course with the Daley machine taught him a second curriculum: attention converts into concessions if you spend it correctly. PUSH conducted voter registration drives, hosted seminars on local candidates, and backed its own slate of aldermanic hopefuls to weaken Daley’s grip on Black wards. Jackson endorsed both Democrats and Republicans when it served his purposes, a flexibility that infuriated party loyalists and kept his adversaries guessing. His record at the polls was uneven. Many of his preferred candidates lost, and critics noted that Jackson frequently declined to grind out the door-knocking and vote-pulling that would have saved them. His strength was pressure applied through visibility, not precinct-level organization. He needed the camera and the microphone to produce his best results, and he knew it.

Around the time he announced his first presidential campaign in 1983, Jackson had spent two decades testing every lever available to a Black leader without elected office. He had boycotted grocery chains, negotiated corporate covenants, confronted a city boss, registered voters in the rural South county by county, and brokered the release of a captured Navy pilot from Syria in a trip so audacious that his own Secret Service detail was secretly swapped for a fresh group of agents once he landed in Damascus. The presidency felt to him like the natural extension of this work, not a wild leap. His critics, including many in the Black political establishment who referred to themselves privately as “the Family,” begged him not to run. They feared he would embarrass the race, split the Democratic vote, and provoke a white backlash that would re-elect Ronald Reagan.

Jackson ran anyway. The 1984 campaign was chaotic, underfunded, understaffed, and burdened by the “Hymietown” crisis, a derogatory remark about New York’s Jewish community that Jackson initially denied and then agonizingly apologized for over the course of weeks. His association with Louis Farrakhan compounded the damage. Mondale’s campaign worked to block Jackson at every turn, deploying its superior organization to prevent Black political organizations from endorsing him. The delegate rules, Jackson argued, were rigged to punish outsider candidates. He was right, and multiple rivals eventually agreed with him.

But the campaign also registered more than a million new voters, won 3.5 million primary votes, and cracked open a door that every progressive candidate would eventually walk through. In Georgia, exit polls revealed that twenty percent of Black voters who supported Jackson were casting ballots for the first time. Young people, Arab Americans, Latino organizers, Asian American housing activists, and Native rights groups poured into his coalition. Each brought their own cause, and Jackson stitched them together under a single argument. The word he used for this was “rainbow,” borrowed from Fred Hampton, the Black Panther leader assassinated by Chicago police in 1969, who had coined the concept of a “rainbow coalition” long before Jackson made it famous.

His 1984 convention address landed on a sweltering July evening in San Francisco. Thirty-three million Americans watched as he spoke for more than an hour. His voice opened even and measured, building by degrees the way a preacher’s voice ascends through a Sunday sermon. The crowd in the hall pushed him forward with shouts that grew louder as each passage crested. “If, in my low moments, in word, deed or attitude, through some error of temper, taste or tone, I have caused anyone discomfort, created pain or revived someone’s fears, that was not my truest self,” he said, and the arena swelled around the admission. Without repeating the slur, he was addressing the Hymietown fallout directly, and the audience grasped both what he confessed and what he asked for. The speech closed with him stripping himself down to the facts of his origin: a boy born out of wedlock in Greenville, South Carolina, who had no right to be on this stage by any measure the country normally applied. “God is not finished with me yet,” he said, and the hall erupted.

Four years later, Jackson returned with a professional campaign operation, a Jewish campaign manager named Jerry Austin from the Bronx, and a strategy built around Iowa, New Hampshire, and the Super Tuesday primaries in the South. Austin discovered immediately that Jackson was useless in a recording studio. Scripted lines died in his mouth. But in front of a live crowd, the man transformed. Austin cut a thirty-second television spot from rally footage of Jackson speaking to farmers and aired it across Iowa’s agricultural communities.

The farm crisis of the 1980s had gutted rural America. Interest rates had climbed to levels unseen since the nineteenth century. Farm debt doubled between 1978 and 1984. Net farm income collapsed from $22.8 billion in 1980 to $8.2 billion three years later. Thousands of families defaulted, banks shuttered, Main Street businesses boarded their windows. No major candidate in either party was speaking directly to these communities. Jackson arrived in Adair County, Iowa, on a bone-chilling day and drew a crowd that outnumbered the town’s entire population. Dairy farmers told journalists he “really touched a nerve.” At a town square rally in Iowa Falls, where Farmland Foods had just shut down a packing plant, Jackson proclaimed, “We must change the equation. There’s no sense of corporate justice, of fairness.” In a Wisconsin barn packed with white farm families who came out of curiosity rather than allegiance, Jackson delivered a speech so consuming that by the time he finished, skeptics were chanting “Win, Jesse, win!” Parents lifted children to see him. Teenage girls giggled over his looks. Former Klansmen from Beaumont, Texas, approached him to say they had changed.

Jackson placed fourth in Iowa with eight percent, an improvement over 1984 and a small but measurable crack in the all-white electorate. He took second in Maine with twenty-eight percent, won the Vermont caucus outright, and then tore through Super Tuesday, winning five states and finishing a strong second in the delegate count behind Dukakis. Bernie Sanders, who had watched Jackson speak to Iowa farmers from afar, endorsed him during Vermont’s nominating convention. “He was there when we needed him,” Sanders told the crowd. “He has stood with the farmers being thrown off the land. He has stood with the workers being thrown off the picket lines.” One woman in the hall slapped Sanders across the face for the endorsement. Others turned their backs. Sanders campaigned for Jackson anyway.

Jackson finished the 1988 primary in second place, winning seven million votes, carrying thirteen states and the District of Columbia, and assembling the most racially diverse coalition the Democratic Party had ever seen. He pushed the party to adopt proportional delegate allocation, replacing the winner-take-all system that locked out insurgent candidates. Barack Obama’s path to the White House cut directly through the breach Jackson forced open. Donna Brazile, Minyon Moore, Yolanda Caraway, Leah Daughtry, Ron Brown, Alexis Herman, Maxine Waters, Barbara Lee—each of these people entered the machinery of Democratic politics through Jackson’s campaigns and spent the next three decades shaping the party from within.

Jackson fathered a child with a former staff member, which became public in 2001. His association with Farrakhan dogged him for decades. His organizational finances were perpetually chaotic, his temper toward staff members often brutal, his ego as enormous as his talent. One staffer described “constant unwarranted abuse.” Another recalled Jackson screaming at his team after they forgot to book a plane, leaving the entire campaign stranded at an Iowa airport in the cold. “I’ve had enough of this ‘Well, I tried, but he lied, so we died,’ excuses,” he fumed. Total control was his default. He disclosed tomorrow’s schedule to reporters by phone from his hotel room before his own staff knew the plan, and he exhausted every person who worked for him. These were real costs extracted from real people, and they coexisted with the generosity, vision, and stubbornness that powered everything else.

Jesse Jackson died this morning, February 17, 2026, at the age of eighty-four. His family announced it in a statement from the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, the organization he led for more than fifty years.

Now the question moves to the rooms where the phrase was born. “I am somebody” was never meant to hang on a wall or sit under a yearbook photo. It was designed to be repeated, out loud, in a room with other people, until the sentence stopped being words and started being attitudinize. Jackson understood that dignity without economic consequence was decoration. His chant always traveled alongside a specific demand: hire these workers, deposit money in these banks, contract with these businesses, register these voters, change these rules. Strip the demand from the chant and you have a greeting card. Keep them together and you have a discipline.

That discipline survives a man only if people keep repeating it where decisions happen. A union organizer in Memphis quotes the sanitation workers’ sign—I AM A MAN—before walking into a contract negotiation. Voter protection volunteers in Georgia make sure every provisional ballot gets counted. A community group in Chicago demands that a grocery chain stock fresh produce in a neighborhood it neglected for a decade. Tenant organizers in Newark pressure a developer to include affordable units. A twenty-three-year-old precinct captain knocks on a door in Milwaukee and explains to somebody who has never voted that their name belongs on a roll.

A first-grader stands in front of a class, feet planted apart, and says the five words because a teacher asked her to. She does not know yet what they will cost or what they can buy. She only knows that when she says them, the other children say them back, and the room fills with a sound that belongs to all of them at once.