July 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from Clipse to Raekwon, here are notable releases in July that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

July, the month that usually gets written off as a musical afterthought, has quietly become a listening party for anyone willing to look past the marquee. While the spotlight settles on the thunderous homecoming everyone’s been waiting for, the real story is in the quieter corners: a brass ensemble turning city heat into slow-motion fireworks, a singer from Oakland handing out unfiltered love lessons, one rapper mapping divinity onto cracked sidewalks, three strangers in a Los Angeles room proving that silence can be the loudest solo of all, and plenty others. No headlines necessary—just press play on our best releases, and let July speak for itself.

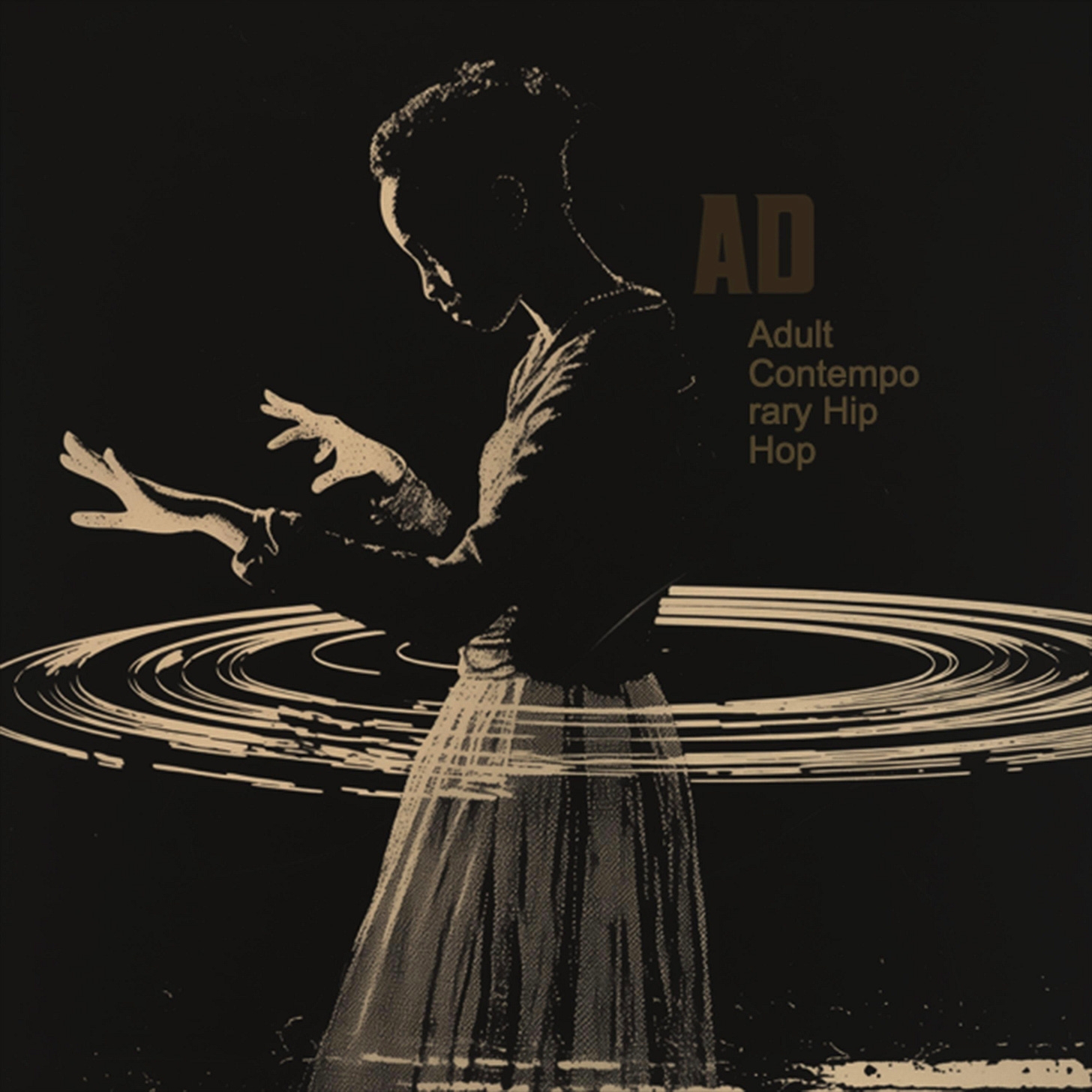

Arrested Development, Adult Contemporary Hip Hop

The Atlanta collective leans into middle-age wisdom with unabashed confidence, with Configa crafting beats that breathe with jazz-inflected patience, where the rapping on this project navigates themes of melanin pride and mortality. They abandon any pretense toward youth appeal—this music belongs to grown folks who've survived decades in hip-hop's margins. Speech remains the anchor, his delivery weathered but purposeful, as he addresses a generation that grew up on “Tennessee” but now grapples with mortgages and Medicare. The album’s boldest gambit lies in its title—openly courting the demographic that radio programmers target with smooth jazz and coffee playlists. Yet beneath the self-aware branding lurks genuine artistic ambition, with compositions that reward close listening and political messages that cut deeper than surface-level consciousness. Over the course of an hour, the record occasionally meanders, but when it connects, it proves that hip-hop’s elder statesmen still possess vital perspectives worth documenting. — Randy

Freddie Gibbs & The Alchemist, Alfredo 2

Back in May 2020, when a rented Hollywood condo doubled as a photo set, Freddie Gibbs and The Alchemist shot the Alfredo cover—silver spoon dripping over fettuccine—and forged a rapper-producer pairing that re-centred gangster rap around cinematic understatemen. Five years, two solo detours, and a globe-spanning tour later, they resurface with a sequel, timed for the Summer of Spittas era drop so fans could blast it at cookouts before campaign ads drown out the block speaker. Gibbs bends flows to every contour—baritone croon here, double-time sprint there—keeping the tension taut with the help of Anderson .Paak’s Oxnard rasp marinates “Ensalada,” Larry June glides Bay-area affirmations through “Feeling,” and JID’s Atlanta syllable-storms torch “Gold Feet,” each cameo upping the heat without stealing the plate. The Alchemist rows deep-fried guitar through dusty strings on “Mar-a-Lago,” chops Peruvian surf rock for “Empanadas,” then lets flute and sub-bass circle like vultures on “A Thousand Mountains,” all tracked to two-inch tape with engineer Eddie Sancho punching edits by hand. The new set weighs appetite against fallout; verses flip between five-star indulgence and the anxiety of someone eyeballing the exit while counting plates. We out here slammin’! — Brandon O’Sullivan

DJ Haram, Beside Myself

DJ Haram channels fury into inventive hybrids on her first full‑length, drawing on club beats, heavy guitars, and Middle Eastern percussion to articulate what she has called being “beside herself” with rage over a violent world. “Lifelike” opens with an ominous synth drone and guitar feedback before her voice declares, “I see god, I can’t stand him,” setting the tone for an album that veers between despair and defiance. “IDGAF” juxtaposes sludgy metal riffs and hand‑clap rhythms with darbuka patterns reminiscent of a Syrian Black Sabbath, while “Badass” centers a chant over claustrophobic percussion. Elsewhere, the record folds in Middle Eastern house (“Loneliness Epidemic”), breakbeats that seem to spar with darbuka drums (“Sahel”), and a swaggering violin reminiscent of RZA’s productions on the posse cut “Fishnets.” Its refusal to sit still makes its cathartic release possible; anger and joy, protest and dancefloor bliss are layered rather than segregated, and that complexity leans into dissidence with her. — Harry Brown

Jim Legxacy, Black British Music (2025)

Jim Legxact swerves from Afropop bounce to emo‑guitar licks to crate‑dug sample chops without ever lifting its foot off the gas. “Father” hijacks chipmunk‑soul to wrestle with absent‑dad ache, its punch line—“On the block, I was listening to Mitski”—landing like a wink and a gut check at once. “New David Bowie” pinballs from Bollywood strings to harpsichord rap to neon synths in two restless minutes. The stadium‑sized riff powering “06 Wayne Rooney” shoves him toward pop‑punk spectacle without sanding off his Lewisham drawl. Outside producers sneak in, yet the fingerprint stays Legxacy’s—distorted drums, abrupt sample collisions, and memories soldered into collage‑pop that invites Jai Paul comparisons. Rather than defining a genre, Black British Music maps one artist’s inheritance in real time—grief, bravado, and bruised optimism stitched together so crudely and convincingly that the seams feel like part of the beat. — Ameenah Laquita

Cleo Reed, Cuntry

Cleo Reed filled the Brooklyn Museum atrium with shadow-puppet projections while premiering songs from the self-released Root Cause EP, looping banjo plucks and Ableton-warped sirens until passers-by mistook the lobby for a picket line. Countless van voice notes, and a season of wildfire haze later, the multidisciplinary artist delivers Cuntry, driven by a need to catalogue survival tactics forged at the intersections of queerness, Blackness, and labor precarity. Reed self-produces but invites Matthew Jamal’s bowed double-bass, Isa Reyes’ processed field recordings, and billy woods’ gravelly poetry to craft an electronic-folk hybrid where foot-stomp percussion collides with glitching modular patches. Nick Hakim whispers falsetto on “Get a Grip,” Elliott Skinner’s choral stack lifts “Women at War,” and Annahstasia drapes “Americana” in reverb-soaked twang, tracing a sonic road trip from borough stoops to desert highways. Cuntry spotlights lineage, from hip-hop raconteur to soul stylist to folksinger—echoing the record’s thesis that no movement advances on a single genre’s shoulders. — Brandon O’Sullivan

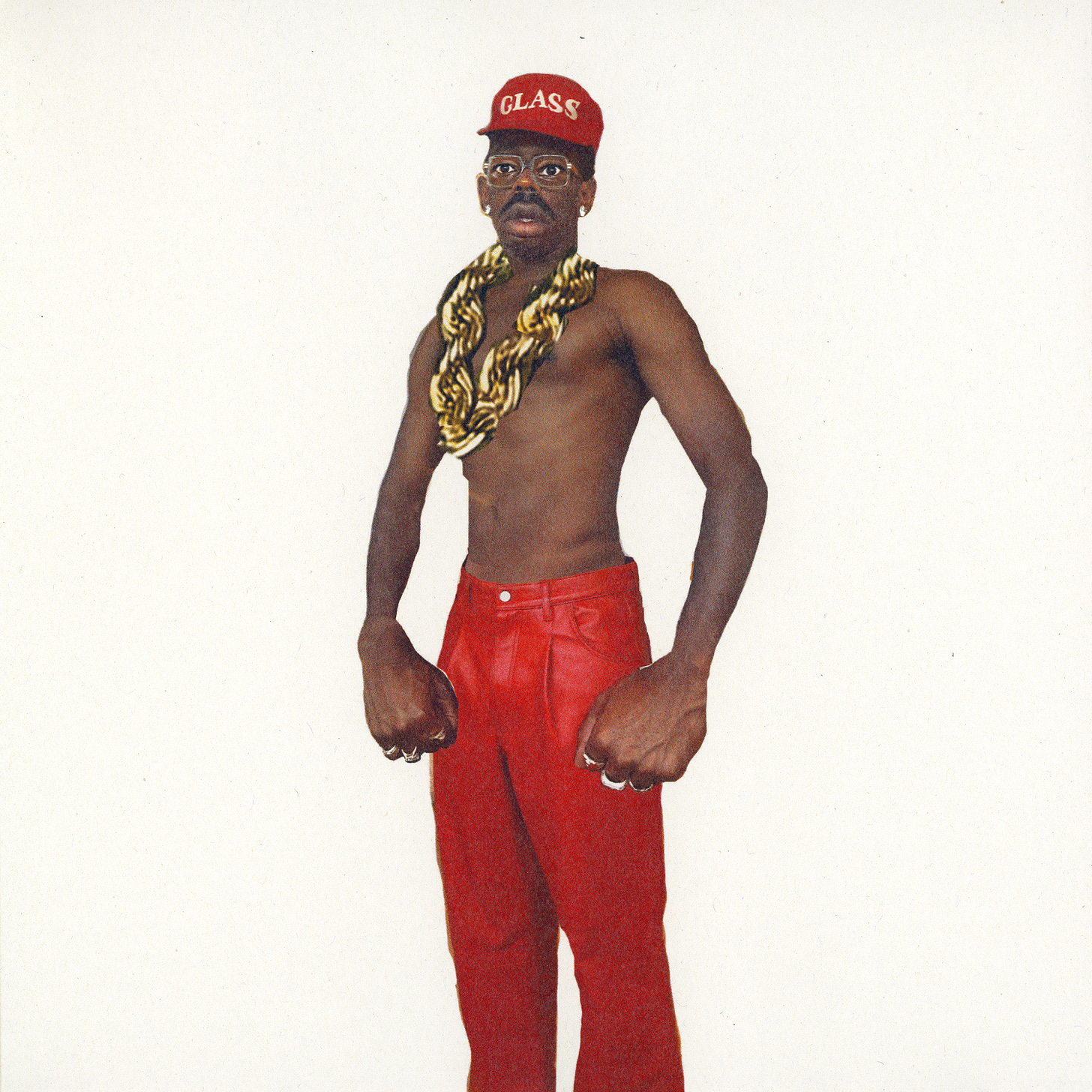

Tyler, The Creator, Don’t Tap the Glass

Tyler, The Creator gate-crashes midsummer with Don’t Tap the Glass, surprise-dropped after arena shows teased only cryptic stage art, answering a personal itch to restore physical movement to rap after the ponderous Chromakopia cycle. The record pinpoints one idea—reclaiming uninhibited joy from screens that freeze crowds, treating every hook as a dare to sweat or stay virtual. Tyler mans every fader, stacking grease-slapped bass riffs and 808 kicks around jagged funk guitars, then flips a Shye Ben Tzur–Jonny Greenwood raga sample on opener “Big Poe,” while Pharrell slides sly half-bars under the low-end like secret hinges. Ray Parker, Jr. punctuates “Ring Ring Ring,” Baby Keem screams ad-libs through a phone filter on “Don’t Tap That Glass / Tweakin’,” and Madison McFerrin’s airy stacks lift the Miami Bass-inspired “Don’t You Worry Baby.” Later, Princess and Killa C ride a Crime Mob interpolation for “I’ll Take Care of You,” tugging Tyler toward crunk before organ swells reset the groove. — LeMarcus

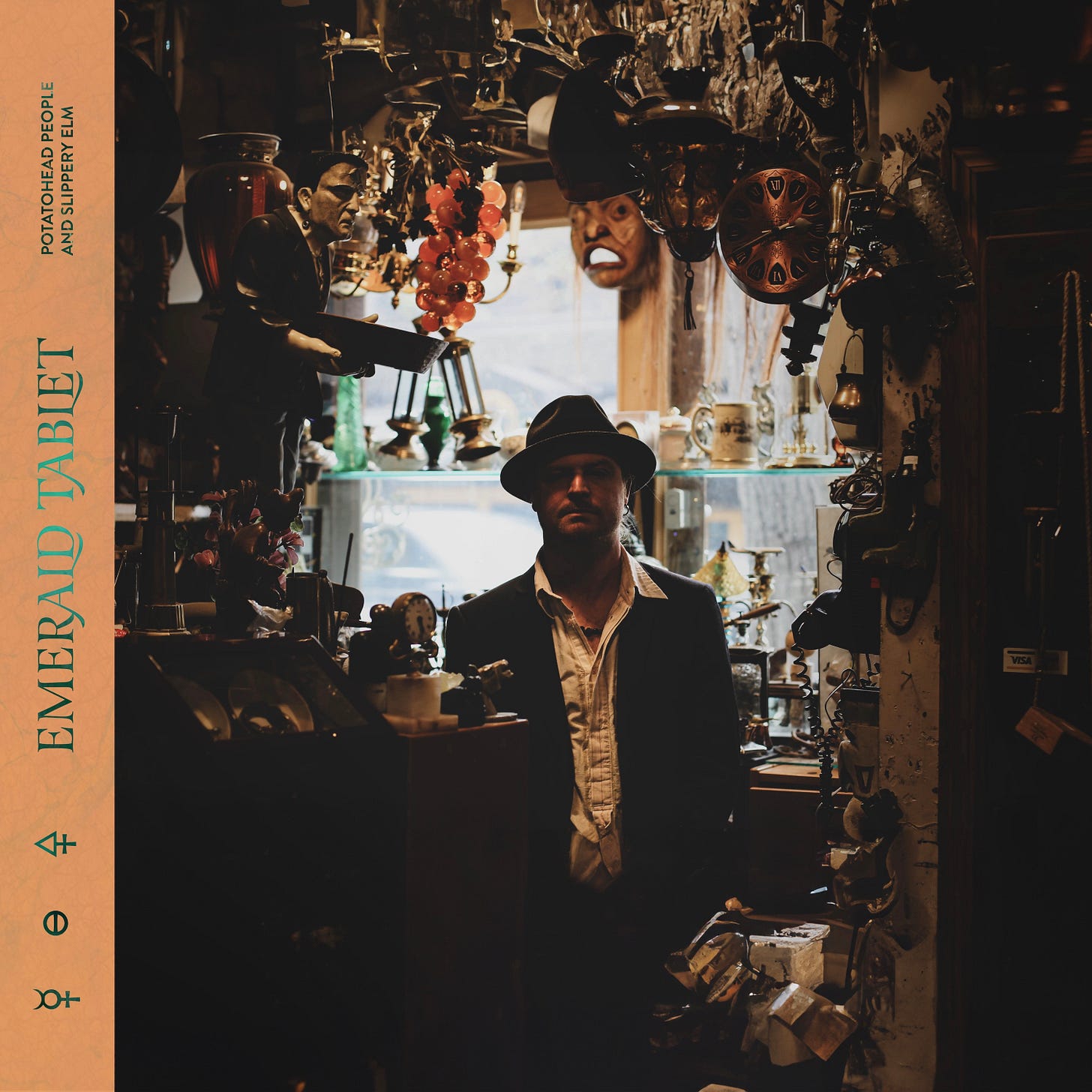

Potatohead People & Slippery Elm, Emerald Tablet

Potatohead People and Slippery Elm prove that hip-hop can be intellectually stimulating and immediately satisfying. The Canadian trio strikes a golden ratio between live instrumentation and sampled textures, drawing from vintage hip-hop. Slippery Elm’s vocals float across the mix like smoke, his measured cadence complementing rather than dominating the Potatohead People's meticulous production work. “Nightbird” explore the interplay between fate and free will, while guest appearances from Bahamadia and Taraneh add crucial variety to the proceedings. The listening experience feels breezy and classy, offering feel-good vibes that never sacrifice sophistication for accessibility. — Oliver I. Martin

Raekwon, The Emperor’s New Clothes

Raekwon leans into preservation rather than reinvention, and his reverence for classic rap aesthetics informs both the production and the writing. The beats are plush and ornamental, with Swizz Beatz adding orchestral flourishes on the Wu-Massacre “600 School” collaboration and J.U.S.T.I.C.E. League layering glossy soul touches across the record, yet the mood remains conservative boom‑bap rather than anything experimental. “Bear Hill” glides on a lounge‑style loop, while “Pomogranite” and “Wild Corsicans” dip into chipmunk soul and boom‑bap to eulogise friends lost to violence. Nas lends weight to “The Omerta,” and Westside Gunn, Conway the Machine, and Benny the Butcher add grit—yet the focus never shifts from his measured delivery. Throughout, Raekwon sounds comfortable, not urgent; he prioritizes authenticity and truth over contemporary fashion, and the album’s strength stems from this calm sense of authority rather than any desire to reinvent himself. — Brandon O’Sullivan

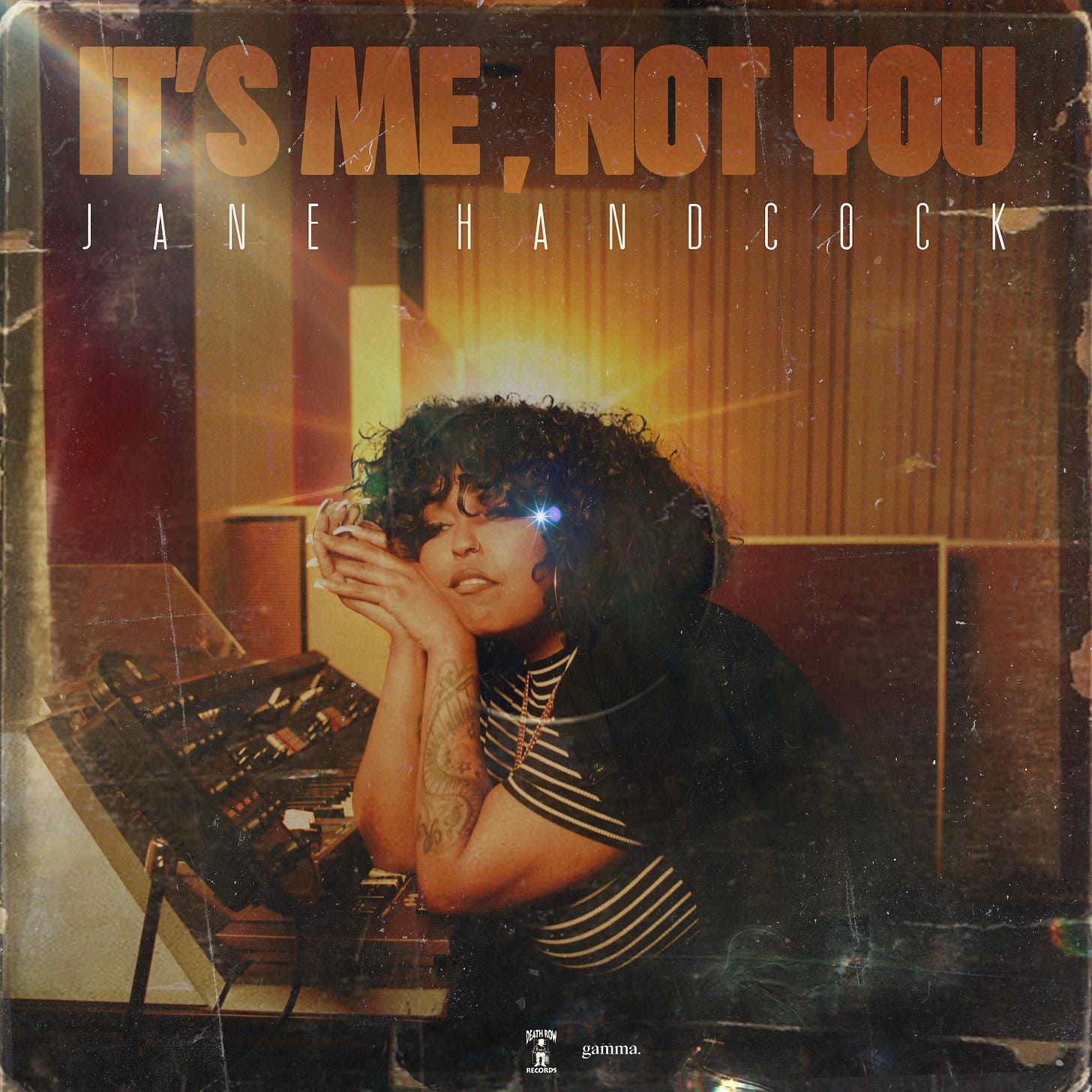

Jane Handcock, It’s Me Not You

Oakland’s Jane opens the door in fuzzy house slippers, pours you something brown and strong, then spends forty-seven minutes explaining why every failed romance was actually syllabus material. She glides from dusty boom-bap to shimmering west-coast funk without ever losing the living-room intimacy of two friends talking past midnight. “Use Me” rides a Soopafly loop that knocks like an aged Impala trunk while Jane’s alto flips between sung confession and half-rapped punch lines, admitting she liked being needed more than she liked the man who needed her. “Sorry” adds splashes of electric guitar that sting like slammed doors, and by the time BJ the Chicago Kid gets a chance to slide into “You,” the album has become a duet cycle—lovers trading accountability like a joint they both know is almost out. Anderson .Paak brings his rubber-limbed drums to “Stare at Me” and the groove struts straight out of a downtown loft party; “Stingy” coos possessiveness over finger-snaps so laid-back they’re practically horizontal. Yet the quietest moments cut deepest—on “Niraj,” Jane sings over Charlie Bereal’s lone guitar, addressing the kind of beautiful disaster everyone swears off until the next text lights up the screen. On It’s Me Not You, she’s no longer blaming exes; she’s watching new love rise like heat shimmer over summer asphalt and deciding, cautiously, to walk toward it. — Jamila W.

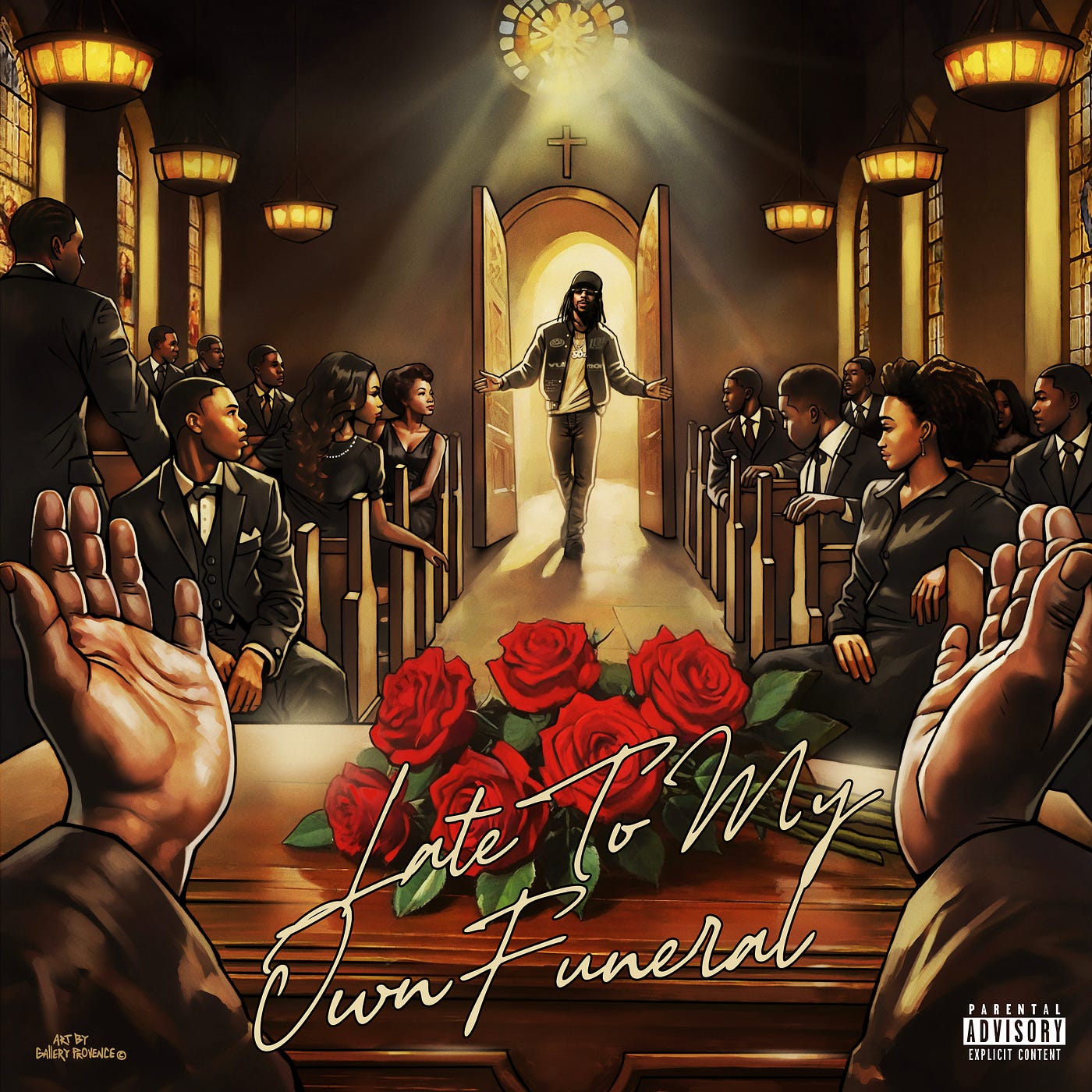

Nicholas Craven & Boldy James, Late to My Own Funeral

Detroit veteran and Canadian producer deliver their third collaboration, Boldy’s seventh project of 2025, that finds both artists at their most refined. “Spider Webbing Windshields” immediately establishes Craven’s chipmunk soul and drumless production style, which has become his signature. Boldy’s signature calm, almost whispered tone carries tracks like “Marrero” and “Trapezoid” with the confidence of someone who has survived every scenario he describes; his distinctive monotone delivery creates hypnotic rhythms that pull listeners deeper into Detroit street narratives. Craven’s production demonstrates his evolution since their previous collaborations, Penalty of Leadership and Fair Exchange No Robbery, with beats that feel both vintage and contemporary without chasing trends. Late to My Own Funeral has its share of catchy hooks, but more often allows Nicholas Craven’s beats to carry these bridges as Boldy James dives into some of his most dense verses to date. — Murffey Zavier

Clipse, Let God Sort Em Out

After sixteen years of silence, the Thornton brothers step back into the same room and decide that nothing about the Virginia they once painted has become prettier. The beats arrive almost entirely from Pharrell, stripped of the starry-eyed chrome that once glittered on Hell Hath No Fury and replaced by something colder, closer to bone. Guitars sound like rust flaking off abandoned cranes (thank you, Lenny Kravitz), drums hit like someone counting losses, and the basslines sway like faulty streetlights. Over this skeletal landscape, Pusha and Malice trade verses that feel like depositions and confessions taped on the same cassette. They mourn parents on the opener, recounting funerals where “the birds don’t sing, they screech in pain” while John Legend’s choir levitates behind them like remembered hymns. Kendrick arrives on “Chains & Whips” and the two camps swap parables about ownership, each syllable measured in shackles and stock options. Tyler brings cartoon menace to “P.O.V.”, Nas closes the record with a eulogy for the block that raised them all, and through every cameo, the brothers remain the eye of the storm—precise, unhurried, speaking of dope still hidden in baby pictures and of brothers who became cautionary tales before they turned twenty-five. There is no fat, no victory lap, only the sound of two men weighing every dollar, every body, every prayer against the scale of their own survival. — Phil

Sækyi, Lost in America

Chicago’s Sækyi transforms the specific loneliness of cultural displacement into some of the year's most compelling hip-hop on Lost in America. As both producer and rapper, he creates these cinematic soundscapes that swing with jazz-influenced samples while hitting hard enough to satisfy heads who need their beats to knock. The title track is a confession, with Sækyi opening with the raw admission that he’s “lost in a stolen land son of a broken man” over production that mirrors his fractured mental state. His vocals shift seamlessly between sung melodies and rapid-fire verses, his delivery always matching the emotional terrain of each song as he navigates what it means to be someone who doesn’t fit the prescribed categories of America. He gravitates toward loops that feel like movie scenes, building atmospheres that support rather than overwhelm his storytelling about family trauma and cultural disconnect. His writing avoids easy answers about identity and belonging, instead presenting questions that resonate far beyond his specific experience as someone caught between cultures, examining how generational pain gets passed down through immigrant families. What’s remarkable is how Sækyi manages to create music about feeling lost that provides direction for those dealing with displacement, turning personal confusion into universal understanding. — Brandon O’Sullivan

FELIVAND, My Body’s My True North

FELIVAND has always made music that feels like late-night conversations with yourself, but My Body’s My True North takes that intimacy to another level entirely. Felicity Vanderveen spent the last few years figuring out how to trust her instincts over everyone else's expectations, and this album is her thesis statement on following your gut when your brain won't shut up. “Water Off Your Back” sets the tone with its shimmering guitar work, which gradually dissolves into layered vocals, creating a cocoon of sound that makes you want to lean in closer. Vanderveen's voice is the real star here—sometimes it’s a whisper that makes you hold your breath, other times it soars with the confidence of someone who's finally figured something out. The production throughout feels deliberately unpolished in the best way possible, with drums that breathe naturally and synths that bloom instead of attack. “Sadie" might be the album’s most immediately gripping moment, built around a bassline that pulses like a heartbeat while Vanderveen explores what it means to trust someone else when you're still learning to trust yourself. “Tired” doesn’t apologize for exhaustion but instead finds power in admitting when your body needs rest. It’s the kind of song that hits differently depending on what you've been through that day. — Imani Raven

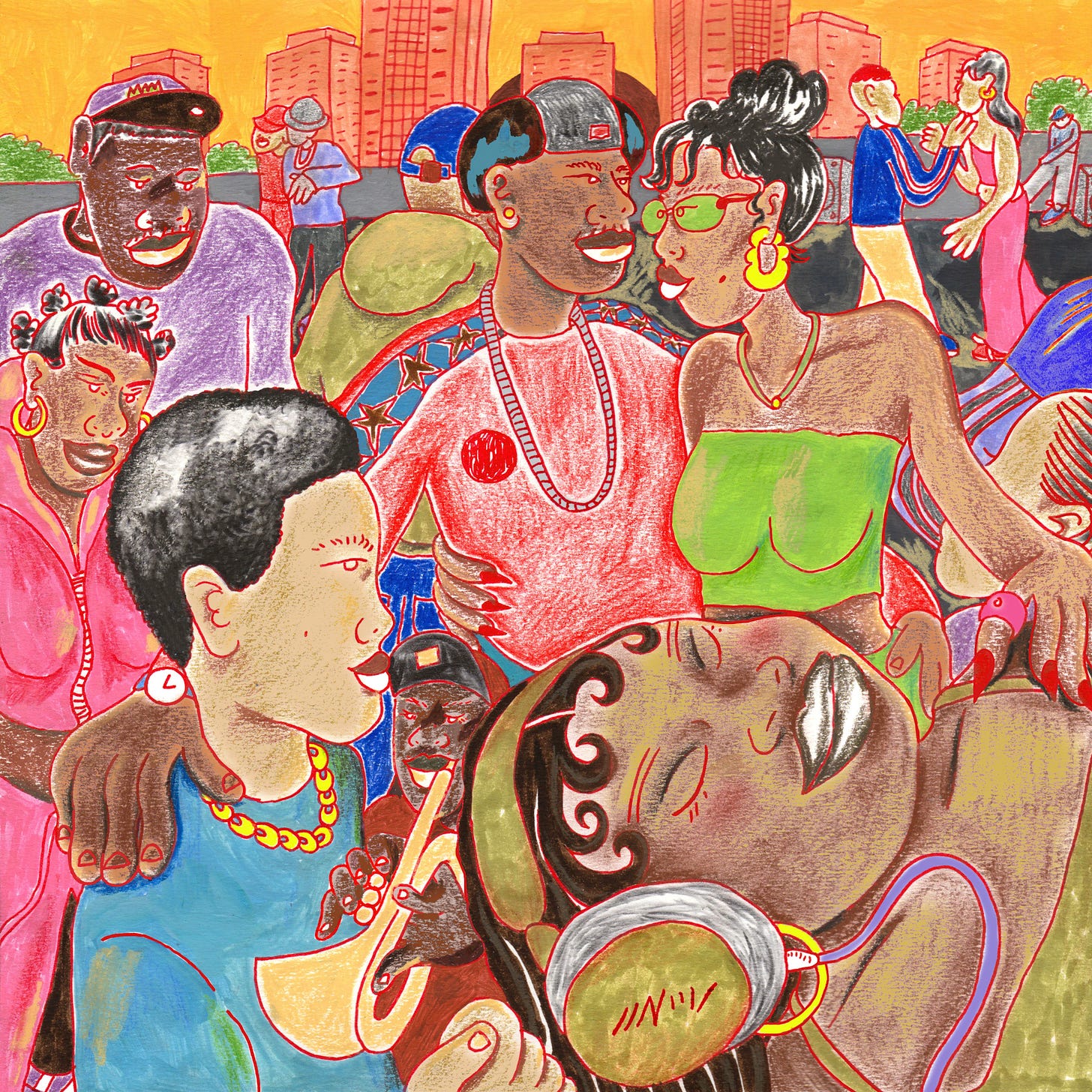

Open Mike Eagle, Neighborhood Gods Unlimited

Beats from Kenny Segal, Exile, and Open Mike Eagle himself smear soul samples, broken synths, and found audio into a soundscape that feels like walking past thirteen front porches, each one hosting its tiny orchestra. He returns to the concept album with Neighborhood Gods Unlimited as if it were a half-remembered dream he’s ready to finish. The neighborhood in question is both his native Chicago and any place where corner stores sell loosies and memories for a dollar. Gods appear in small forms: a barber who claims he once cut Common’s hair, a cashier who speaks in Gil Scott fragments, a kid on a BMX who swears he can outrun the surveillance drones. Mike narrates with the resigned awe of someone who has seen every miracle downgraded to rumor yet still wants to believe. On “Lease Agreement With the Universe,” he raps about gentrification as a divine contract printed in vanishing ink, while “Argue With the DJ” turns a skipped 45 into a theological debate between fate and free will. — Harry Brown

Nate Mercereau, Josh Johnson & Carlos Niño, Openness Trio

Three improvisers walk into a room in Los Angeles with no charts, no safety net, and a shared belief that melody can be negotiated in real time. Mercereau’s guitar sometimes behaves like a pedal steel lost in space, bending notes until they cry or laugh depending on the afternoon light. Johnson’s alto and flute arrive like birds that trust the windows have been left open on purpose; he circles themes, lands, then lifts off again before the listener can decide whether they were phrases or prayers. Niño’s percussion is less time-keeper than weather system—gongs suggest distant thunder, shakers imitate wind through palms, and a lone kick drum pulses like the city breathing two blocks away. Across four long pieces, the trio practices radical listening. A single chord can linger long enough to become architecture; a sudden flurry of notes might evaporate before you can photograph it. You leave the room lighter, convinced that openness is not a posture but a practice. — Nehemiah

Kae Tempest, Self-Titled

“How many strangers will I upset with my existence today?” sparks “I Stand on the Line,” foregrounding Kae Tempest’s battle between public visibility and private peace. Their fifth studio set follows 2022’s The Line Is a Curve yet narrows personnel to a rhythm section and producer Fraser T. Smith, creating maximal space for syllabic weight. By choosing to self-title the album at this juncture, Tempest signals a reclamation and redefinition of their artistic identity, aligning their public persona more closely with their lived experience, particularly following their public coming out as transgender. Another significant track, “Know Yourself,” features a poignant internal dialogue between Tempest’s present self and a younger version, exploring the complexities of self-discovery, identity formation, and the passage of time. This introspective quality is a hallmark of the album, as Tempest grapples with personal history, relationships, and the ongoing process of self-discovery. Alongside these deeply personal narratives, the album continues Tempest's tradition of social critique, likely examining issues of power, inequality, and the human condition within modern society. — Charlotte Rochel

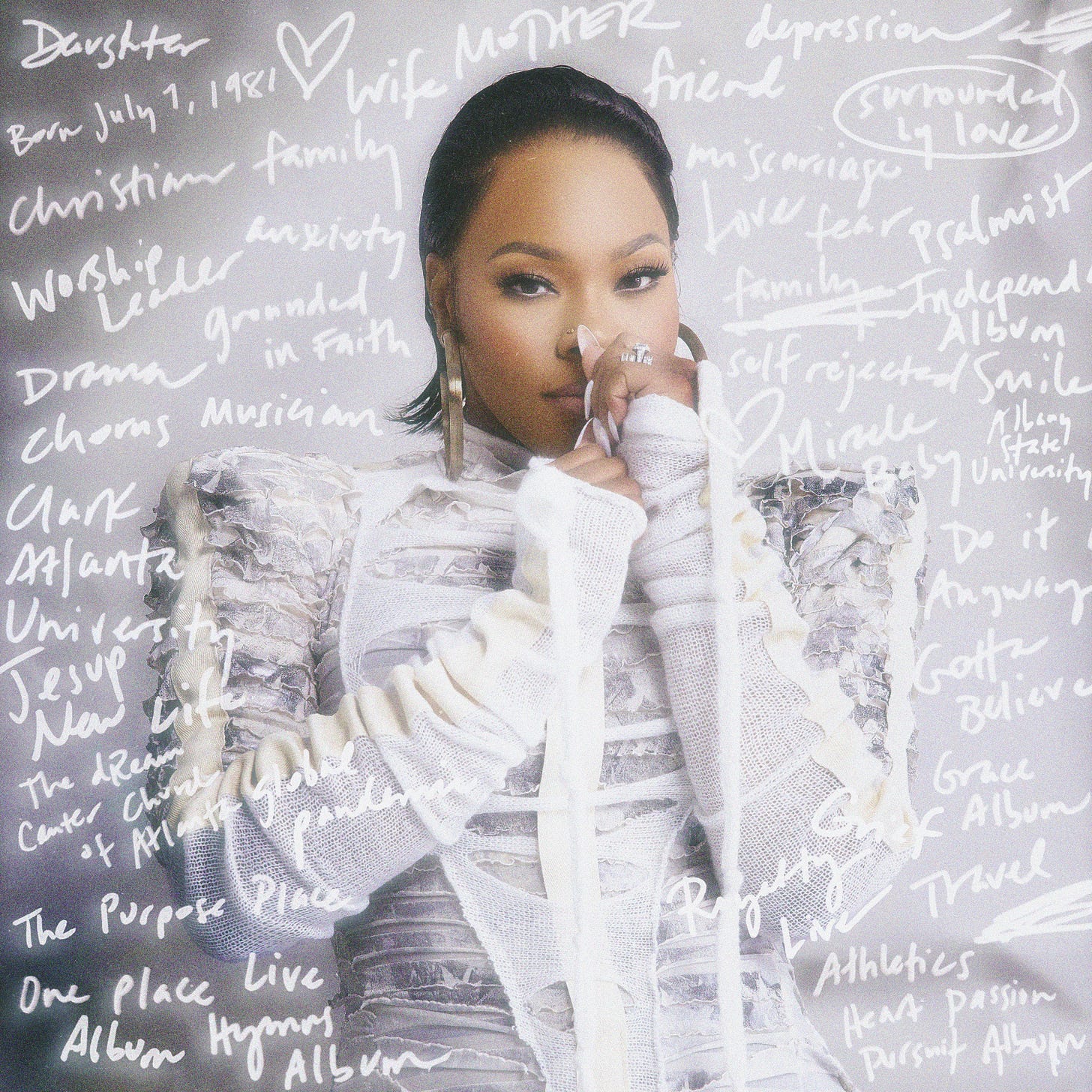

Tasha Cobbs Leonard, Tasha

Cobbs Leonard swaps live-wire arena bombast for something closer to a testimony, letting a raw piano-and-choir framework carry songs that consider faith as restless dialogue rather than fixed proclamation. “Church,” a duet with John Legend, turns the sanctuary inside-out, featuring two voices trading small, unvarnished pleas while the choir hovers like held breath, underscoring her push to root devotion in everyday language. “I Want More” leans into Chandler Moore’s gentle stack of harmonies, the pair circling a single descending chord until craving feels tangible, almost physical. Elsewhere, bursts of ‘80s R&B brass brush against clipped hip-hop drums, hinting at the genre fluidity she’s courting without drowning the core gospel pulse. Throughout, Cobbs Leonard sings from the middle of the struggle—shaky certainty, ragged gratitude, open-throated need—showing how confession can stretch into praise without changing its key. — Tai Lawson

Kokoroko, Tuff Times Never Last

London’s brass-heavy family returns with eleven pieces that feel like open windows in July, letting the city’s humid breath drift through. Sheila Maurice-Grey’s trumpet and Anoushka Nanguy’s trombone circle each other like cousins trading jokes at a barbecue, while Yohan Kebede’s Rhodes chords smolder like charcoal left glowing after the food is gone. “Never Lost” begins with a wordless lullaby that sounds like sunlight on wet pavement, and from there the record wanders through memories. “Sweetie” stirs Afrobeat polyrhythms into the mix until the horns burst into exclamations too joyful to stay pent up. Lulu appears on “Idea 5 (Call My Name)” and stretches the groove into late-night neo-soul, her voice sliding across the brass like fingertips on bare shoulders. The miracle is how nothing feels rushed on Tuff Times Never Last. Even when the band edges toward melancholy—“My Father in Heaven” glows with gospel ache—the pulse remains steady, a reminder that sorrow and celebration can share the same heartbeat. Play it at dusk with the windows open, and the street becomes part of the arrangement. — Imani Raven

Mr. Muthafuckin’ eXquire, Vol. 2: The Y.O.Uprint

Brooklyn’s wild card turns an acronym into a running thesis, flipping “Y.O.U.” from taunt to prayer across beats that hiss like worn cassette stock. “Desire Y.O.U” rides KRILL’s bleary soul loop while eXquire spits double‑back rhymes that treat self‑improvement like street lore. On “It Iz what it iZ,” Iceberg Black’s snarled couplets rub against eXquire’s humor‑laced despair—two voices pacing the same cramped hallway, trading worries for punch lines. Blu drifts through “Absotively Posilutely,” his calm phrasing bending KRILL’s stuttering horns toward daylight. Scratches from A‑Trak streak “The Soloist” with static, but the hook lands softer than the title threatens, hinting at the record’s quiet obsession with accountability. Even at its rowdiest—say, the fever‑rush of “Y.O.Utopia”—the tape circles back to the same question: can swagger and self‑reckoning live in the same verse without drowning each other out? eXquire answers by refusing to choose. — Phil

$ilkMoney, Who Waters the Wilting Giving Tree Once the Leaves Dry Up and Fruits No Longer Bear?

A decade ago, in a cramped Richmond basement where Divine Council tracked their first guerrilla mixtape, $ilkMoney freestyled until the condenser mic fogged, laying the combustible blueprint that still crackles in his delivery. Three years of public radio silence later, he returns with Who Waters the Wilting Giving Tree Once the Leaves Dry Up and Fruits No Longer Bear?, triggered by the question of who keeps nourishing culture after commerce strips it bare and previewed by the splatter-punk single “NEVER TRUST A BITCH THA-*EXPLODES*.” Kahlil Blu’s loops warp soul samples into woozy parables, while Sycho Sid sneaks in brittle snare clusters that thud like folding chairs against ring posts, letting $ilk ride double-time cadences without losing clarity. Forty-four unruly minutes churn refusal into crooked joy; wordplay detonates, beats stagger, yet the pulse—who tends the soil when the harvest gets looted—never wavers, turning self-preservation into an art of surplus rather than retreat now. — Harry Brown

Nice list! A few in there I need to check out. I have Raekwon in my top albums this month too!