June 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from Little Simz to McKinley Dixon, here are notable releases in June that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

As we step toward July, the music world is riding a wave of change. June floated by on a steady tide of intriguing records that favored thoughtful craft over empty spectacle, yet the month also brought high-profile stumbles that missed their mark. The releases (which we’ll get into a little bit) gave the month a quietly confident shine (even though this week could’ve ended better), but Lizzo’s unexpected commercial mixtape My Face Hurts from Smiling, for example, arrived as a tonal outlier that struggled to convert novelty into substance. As we enter a new month and the height of summer, hip-hop and R&B occupy a moment of both tension and vitality. Grounded by craft and legacy, they face the pull of streaming algorithms, AI experimentation, and cultural shifts. Without further ado, let’s deep dive into the albums that stood out to us in June.

Joe Armon-Jones, All the Quiet (Part II)

Joe Armon-Jones handles writing, production, and mixing, fusing jazz harmony with dub atmosphere and easygoing funk grooves on his own terms with this sequel. “Acknowledgement Is Key” lets Hak Baker recount personal struggles over sparse keys and rounded bass, turning conversational snippets into central hooks. “Westmoreland” brings Asheber’s resonant baritone atop a rhythm inspired by sound-system culture, while analogue hiss signals Armon-Jones’s fondness for tactile studio character. Greentea Peng and Wu-Lu share space on “Another Place,” trading melodic lines that glide rather than clash. Yazmin Lacey’s appearance on “One Way Traffic” offers a brief lift before the band settles back into steady motion. Nubya Garcia threads short sax phrases through several sections, never overstaying. Drummer Kwake Bass locks a relaxed pocket that lets keyboard voicings float. Instead of chasing climaxes, Armon-Jones allows ideas to breathe, rewarding jazz fans who stay for detail. — Harry Brown

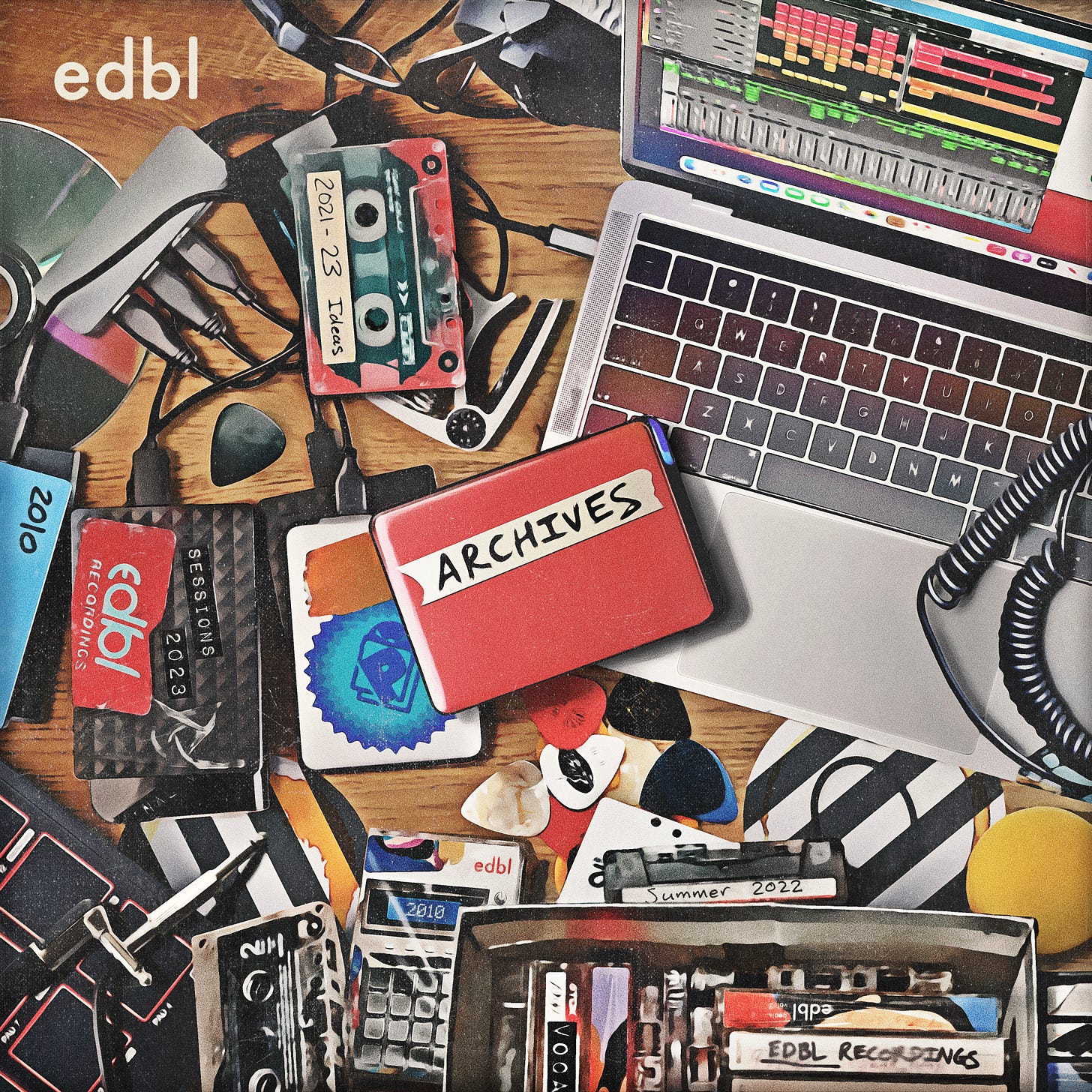

edbl, Archives Mixtape

Across Archives Mixtape, edbl turns four years of voice-note sketches into a living scrapbook, presenting each collaboration as evidence that patient curation can rival real-time spontaneity. “Capitan” opens with bb sway singing over rim-shot drums about feeling adrift in a city that never waits. Albert Gold follows on “Better Now,” repeating “Might be better now, but I still regret,” giving the project its most direct confession. Throughout, edbl’s jazz-schooled guitar licks respond to singers instead of crowding them, placing melodic guidance at the margins of each verse. Keys, bass, and hand percussion stay minimal, placing emphasis on small vocal gestures. “Beneath Your Surface,” with Olivia Nelson, asks for honesty over brushed snare and warm synth pads. By inviting guests to steer themes while he refines pocket-wide grooves, edbl shows archival fragments can mature into coherent statements when patience and curiosity guide selection. — Brandon O’Sullivan

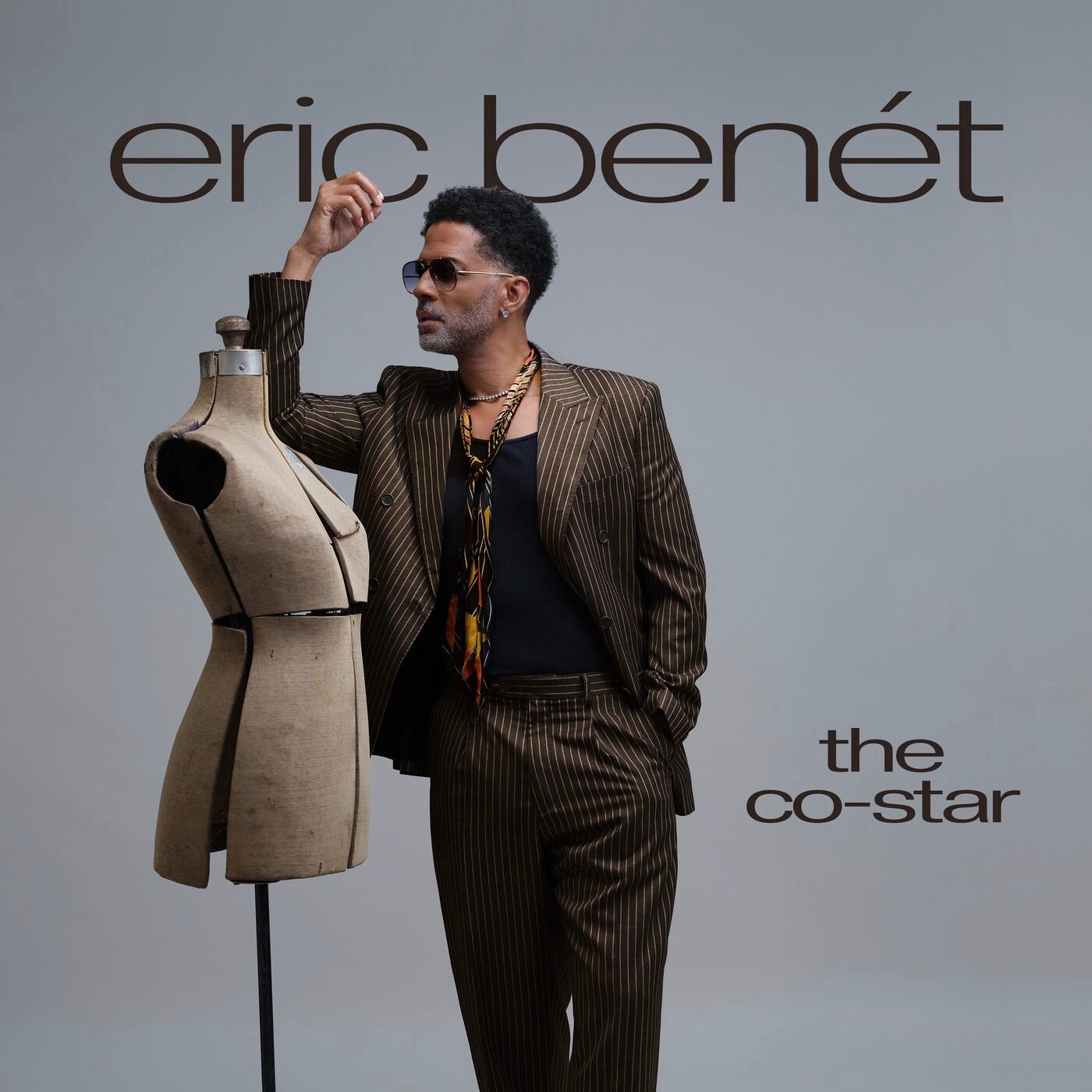

Eric Benét, The Co-Star

Benét pivots from front-stage crooner to skilled partner on The Co-Star into a conversation rather than a showcase, starting with Ari Lennox’s sharp warning on “Gaslight”: “Could’ve been beautiful, but you’re cold and egotistical.” India Arie answers with gentle reassurance on “Must Be Love,” and Corinne Bailey Rae lifts “Fly Away” with light guitar. Live drums, Rhodes keys, and soft horns supply an easy pop-soul cushion that never crowds the singers. Lyrics keep circling trust, apology, and mutual care, so the duets feel like practiced listening sessions. SalDoce slips a samba pattern under “Too Soon,” where patience and regret share space. Judith Hill and Melanie Fiona steer “Southern Pride” and “Me & Mine” toward family themes. Spanish track “Eres Mi Vida,” sung with Pia Toscano, extends the record’s inclusive spirit without novelty. Benét sounds most engaged when partners push back or co-sign his lines, proving the album’s title accurate. — Tabia N. Mullings

Ché Noir, The Color Chocolate 2

Pulling craft from the easel, Ché Noir opens “Painting Class,” declaring, “My pen’s a paintbrush, my words came out the color chocolate,” announcing composition itself as her subject. “Buy vs Sell” pivots into street reportage, following a woman’s fatal slide through addiction with unsparing detail. Later, over Evidence’s somber loop on “Blink Twice,” she quips, “Penny for my thoughts, all intellect when I spit these rhymes, it gave me that IT factor, thought I was Pennywise,” mixing literary reference with hard-won swagger. Detroit stalwart eLZhi turns up on “Who’s the Greatest?” to trade rapid syllables, sharpening the friendly competition at the heart of her pen work. Many songs are self-produced or steered by longtime collaborator C-For, the beats favor single-bar loops and clipped drums that leave rhyme schemes stark in the frame. That restraint makes every internal rhyme sting, establishing the Buffalo emcee’s voice as the project’s most volatile instrument. Though this sequel doubles the material of its 2024 prelude, narrative discipline replaces filler, keeping momentum taut. — Phil

Terrace Martin & Kenyon Dixon, Come As You Are

Within a framework of supple Rhodes chords and barely there drum loops, Terrace Martin and Kenyon Dixon explore self-regard as a communal practice. Dixon speaks plainly about love and vulnerability, offering insight into emotional surrender. Martin complements that with understated yet expressive jazz touches—Robert Glasper and Keyon Harrold add soft flourishes that nod to LA’s rich musical heritage. Rather than spell out gospel influences, the pair fold call-and-response backing lines into slow-bloom arrangements that feel lived-in. Martin keeps his horn cameos sparse so Dixon’s tenor can press forward with plain-spoken reminders to “love yourself” and “keep your circle tight.” Those phrases may read simple on paper, yet the singers treat them as working lessons, revisiting them over subtly shifting keys. When Rapsody drops into “WeMaj,” her measured verse about trusted friendships widens the album’s moral compass without breaking its hush. Keyboards and bass stay in dialogue, moving just enough to suggest forward motion while leaving space for breath. Together, they prove modern R&B can speak softly and still cut deep when craft serves purpose rather than ego. — Phil

Yaya Bey, Do It Afraid

Yaya Bey opens with a mantra of courage: “If you want to be brave, first you gotta be afraid,” and she lives by it across pastoral instrumentals that mix acid jazz, trip-hop, reggae, and soca. She moves between intimate confessions and buoyant grooves. The Caribbean pulse of “Merlot and Grigio,” featuring her Barbadian collaborator, showcases her ease in marrying American soul with diasporic pulses. She addresses emotional labor and misogynoir with upfront candor while never sacrificing the warmth of her voice. The arc is of trudging through fear toward clarity and self-acceptance. She skips between swagger and reflection but keeps it all grounded in a patient groove. Instead of chasing a glossy hook, she leans into conversational cadences that turn everyday grievance into melody. On “End of the World,” muted horns from Butcher Brown bloom behind her voice, framing apocalypse talk as block-party small talk. Elsewhere, “Real Yearners Unite” pares instrumentation to finger snaps, allowing the singer to confess that craving tenderness can feel defiant. By keeping production minimal and language direct, she turns personal risk into a shareable blueprint for survival. — Jamila W.

Theo Croker, Dream Manifest

Theo Croker pulls themes from a dream journal, translating them into nine concise instrumentals and vocal collaborations. “Prelude 3” pairs piano with muted trumpet, establishing a relaxed conversation before fuller grooves appear. Estelle and Kassa Overall share gentle lines on “One Pillow,” set against brushed snare and soft bass that keep the mood close. “64 Joints” runs longer, allowing Tyreek McDole to float over slow keys while the rhythm section holds steady. “Up Frequency (Higher)” edges pace upward, yet air remains in the mix for horn flourishes. Gary Bartz joins “Light as a Feather,” trading concise phrases with Croker that favor dialogue over display. MAAD and Malaya add subtle R&B shades on “High Vibrations,” widening the palette without crowding instruments. Croker prefers analog warmth, evident in rounded horn edges and lightly saturated keys. Throughout, Croker prioritizes emotional clarity and collective balance over technical parade, inviting listeners into a quietly imaginative sound world. — Nehemiah

Durand Jones & The Indications, Flowers

From late-night Chicago writing sessions, Durand Jones & The Indications return with a body of work that treats grown-up intimacy as dance-floor fuel. The brief intro “Flowers” leads into “Paradise,” where Aaron Frazer’s falsetto glides over an easy bass line reminiscent of early-‘80s quiet-storm staples. Durand’s fuller tone on “Really Wanna Be With You” provides contrast, turning lyrical pleading into confident assertion. Strings lift the chorus without tipping into nostalgia, signalling the group’s intent to honor predecessors while sidestepping retro cosplay. Shared vocals dominate, a choice that underscores the album’s emphasis on collective resilience rather than individual virtuosity. Many takes were captured live, preserving tiny imperfections that make the grooves human enough to invite repeated spins. “Been So Long” articulates reunion joy with the line “it’s good to be back together,” summing the album’s narrative in everyday language. By balancing disco shimmer with straight-talk sentiment, the band proves maturity and fun can still share the same dance floor. — Imani Raven

Brandee Younger, Gadabout Season

Brandee Younger centers her harp on circular themes that invite a calm, reflective state of mind. Rashaan Carter’s bass and Allan Mednard’s drums supply light propulsion while keeping clear air around the strings. Recorded partly on a restored instrument once used by Alice Coltrane, the set honors lineage without leaning on nostalgia. “Reckoning” opens with a brief, searching figure that reappears in subtle variations later on. Shabaka’s flute on “End Means” slips in like a soft breeze, coloring the mix without turning the spotlight. “Breaking Point” toughens the groove with clipped accents while still leaving room for melodic breathing. Younger wrote every piece, and her intent shows in the disciplined pacing. She avoids flashy runs, aiming instead for motifs that bloom through repetition. Short overdubbed vocal sighs drift through “BBL,” hinting at R&B influence without a full stylistic pivot. Sessions took shape in her Harlem apartment, lending casual intimacy to the recording. By steering away from grand gestures, Younger underlines the harp’s conversational power on Gadabout Season that feels like time well spent in thoughtful company. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Loyle Carner, Hopefully !

Loyle Carner turns away from community narratives and toward domestic life as a father, as his voice is low and conversational, sometimes even humming. He mixes rap and a previously unused croon with his singing voice, which emerges naturally and unforced. He speaks about the weight of being a parent, confessing doubt: “They said my son needs a father, not a rapper,” and “this fear in my belly” during early fatherhood moments. He toys with vulnerability and humility, admitting anxiety and addressing his partner in snapshots of domestic friction. He recalls childhood memories and his mother’s presence with matter‑of‑fact clarity. The music’s warmth is sincere, leaning on dreamy piano, soft drums, and lightly flickered guitar, though at times the tone drifts toward low energy. Still, the personal stakes feel real—he’s trying to figure out how to be both an artist and a caretaker. The record is gentle rather than grand, thoughtful rather than flashy. There is a subtle tension between aspiration and obligation that persists. This feels like a journal of familial love and parental uncertainty delivered calmly but with care. — Murffey Zavier

Nick Grant, I Took It Personal

Nick Grant documents his experiences in the industry and his motivation to assert artistic autonomy, refusing bombast while maintaining technical precision. He alternates between soulful boom-bap and more ominous trap-inflected beats, shifting from proclamations of lyrical supremacy to autobiographical reckonings. In “Let It Reign/Read Your Contract,” he rails against major-label disappointments and cautions aspiring artists, balancing confidence with caution. He explores love on tracks like “Do You Love Me?” where devotion becomes ambition’s fuel, then pivots toward asserting dominance over his underdog narrative on “Big Tymers.” He speaks on street authenticity and competition in pieces like “Love for the Mob” and “Product, User, Dealer,” weaving vivid stories with calm but forceful delivery. In “Nothing’s Free,” he reflects on systemic struggle over darker piano chords. Grant uses his craft to process personal and professional trials without resorting to sentimentality. He asserts himself not just as a rapper but as a figure shaped by industry trials and street tales. — Harry Brown

Leikeli47, Lei Keli ft. 47 / For Promotional Use Only

Leikeli47 begins a new phase by stepping out without her trademark mask, aiming for direct connection under a title that pokes at industry marketing. “450” sets the agenda as she chants “Badness, mi nuh care” over sparse bass and kick, mixing bravado with patois flair. “Soft Serve” flips snack-shop references into a breezy boast that keeps energy light. Across eleven tracks, she moves between rapid-fire bars and catchy hooks without strain. Beat choices favor thick, low-end, and crisp hand claps, placing her voice in clear relief. “Queen” leans on call-and-response chants that stress self-worth. When a dancehall pattern emerges in “Starlight,” the vocal tone shifts to a warning mode, showcasing range without spectacle. Patois phrases and East Coast slang ground her perspective. The decision to appear without her trademark mask aligns with lyrics that trade concealment for straightforward testimony. Lei Keli ft. 47 / For Promotional Use Only captures her versatility while keeping confidence front and center. — Jamila W.

Radamiz & Fortes, LIGHTMAN, the album

Radamiz and Fortes combine their creative strengths to craft a project that feels concise and intentional. The opening tracks hit hard with polished energy and sharp lyrical dexterity, especially “One/Slide,” which others have applauded as among the year’s standout hip-hop tracks. Each recurrence introduces verses that measure ego against humility, delivered at a conversational volume that invites the listener’s proximity. Fortes leans on spacious keys and understated drums, allowing Radamiz to articulate debts, delayed forgiveness, and rent deadlines without sonic clutter. The beats never overwhelm the vocals, offering space for introspection on tracks like “Grace, Grace, Grace.” He navigates themes such as personal growth and self-awareness; on “Step, Step, Step” and “When I Know What to Do,” he poses questions without forced elaboration, maintaining a direct tone. — Javon Bailey

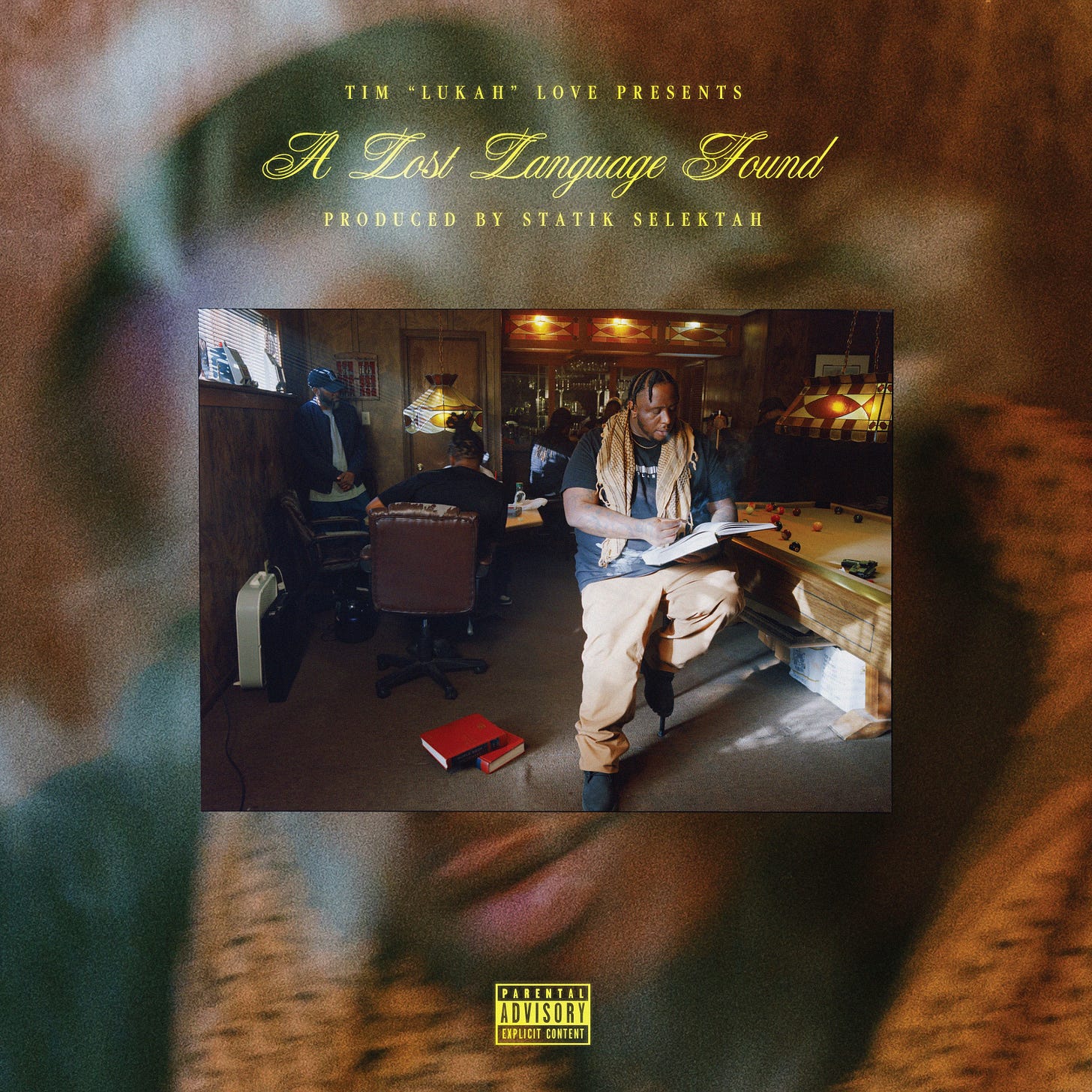

Lukah & Statik Selektah, A Lost Language Found

With Statik Selektah providing crisp drum patterns and minimalist piano loops, Lukah addresses linguistic preservation on A Lost Language Found. “Words Drenched in Acid” questions how marginalized speech survives external dilution, grounding theory in concrete neighborhood anecdotes. Lukah presses forward with urgency and clarity, his lyricism focused on culture, urban reality, and communication. On “Native Tongues” and “My Sermon” (featuring 8Ball), his flow tightens and his themes reach into shared heritage and personal affirmation. Statik’s sequencing builds a cohesive arc that holds together the features and solo verses without diluting Lukah’s voice. Killer Mike joins “South Still Speaking” to affirm dialect resilience, blending Memphis drawl and Atlanta cadence into a unified assertion of Southern identity. The album pays homage to classic East Coast styles while staking new ground in storytelling and sonic layering. It’s earnest without being grandiose, articulate without overcomplication. Between-song banter adds a casual atmosphere and reinforces the sense that the artist is at ease in their element. — Randy

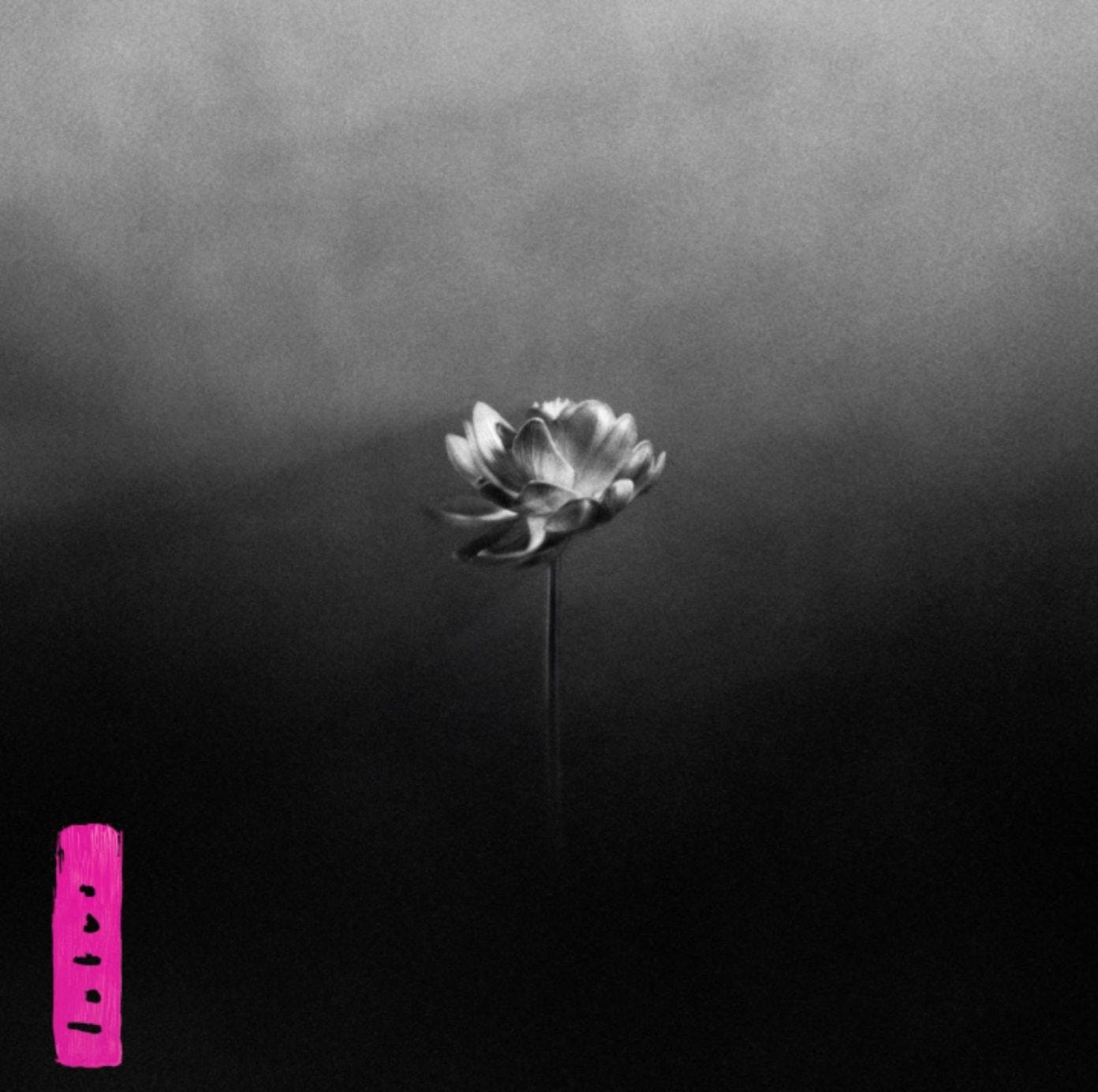

Little Simz, Lotus

Little Simz opens with a bold statement of renewal, trading dense orchestral flourishes for leaner funk guitar and restless live drums engineered by producer Miles Clinton James, her first studio partner since parting with her long-time collaborator. “Thief” spells out money disputes in blunt detail and turns private strain into public warning. The momentum never settles for one groove; “Free” flips between rim-shot bounce and orchestral lift, while “Young” glides on a muted bass figure that lets her speak plainly about generational fatigue. What anchors everything is her phrasing, tightened to near-spoken cadence yet still melodic enough to ride the modal guitar runs Yussef Dayes threads through the back half. The pulsing single “Flood” rolls epic strums with hard-hitting tom hits, detailing shifts from exhaustion to forward motion. She tackles betrayal, burnout, and spiritual repair in a conversational tone that highlights vulnerability over bravado. Her cadence remains conversational, allowing moments of self-doubt to land as hard as her bravado. — Brandon O’Sullivan

McKinley Dixon, Magic, Alive!

McKinley Dixon packs Magic, Alive! with busy horn riffs, crisp drums, and verses that pair survival tales with literary nods. In “Sugar Water,” he raps, “Doing it so that the gold could drape up on my collarbone,” linking ambition to communal uplift. Quelle Chris and Anjimile echo that drive while the beat flickers between jazz chords and hand-clap percussion. “Watch My Hands” opens with promises to stay alert after past violence, setting a sober tone. ICECOLDBISHOP, Pink Siifu, and Teller Bank$ contribute their perspectives on loss, keeping the focus collective rather than personal glory. Voice-memo sketches appear between songs and later return as hooks, making the record feel continuous. Trumpet, flute, and distorted guitar share limited space, yet no part feels forced. Dixon writes about grief in present tense, treating remembrance as work that never stops. The energy stays high enough that reflection sounds like action. — Phil

Maxo, Mars Is Electric

Maxo explores new terrain with a laid-back confidence, choosing introspection over swagger in this set of ten tracks. He adopts a pared-down sound palette built around lo‑fi beats, subdued psychedelia, and electronic minimalism that lets his voice settle into the rhythm rather than dominate it. On the lead single, “Human?,” he reflects on human imperfection with the line “God threw us in the world half damaged,” acknowledging vulnerability without dramatizing it. The tone remains experimental and exploratory, while he’s in a mood of searching and emotional honesty. There’s a sense that this album emerged without preset expectations—Maxo himself said he "didn’t approach things so seriously," and that mindset is audible here. He touches on fractured relationships and loss of innocence in a straightforward, unguarded way. The arrangements shift subtly, layering electronic flourishes and stripped-back drums under his soft-spoken delivery. It’s less about a polished presentation and more about a believable emotional exchange. This is Maxo at a point where experimentation feels natural, not forced. The record suggests autonomy is less about grandeur than about editing until only the honest parts remain. — Brandon O’Sullivan

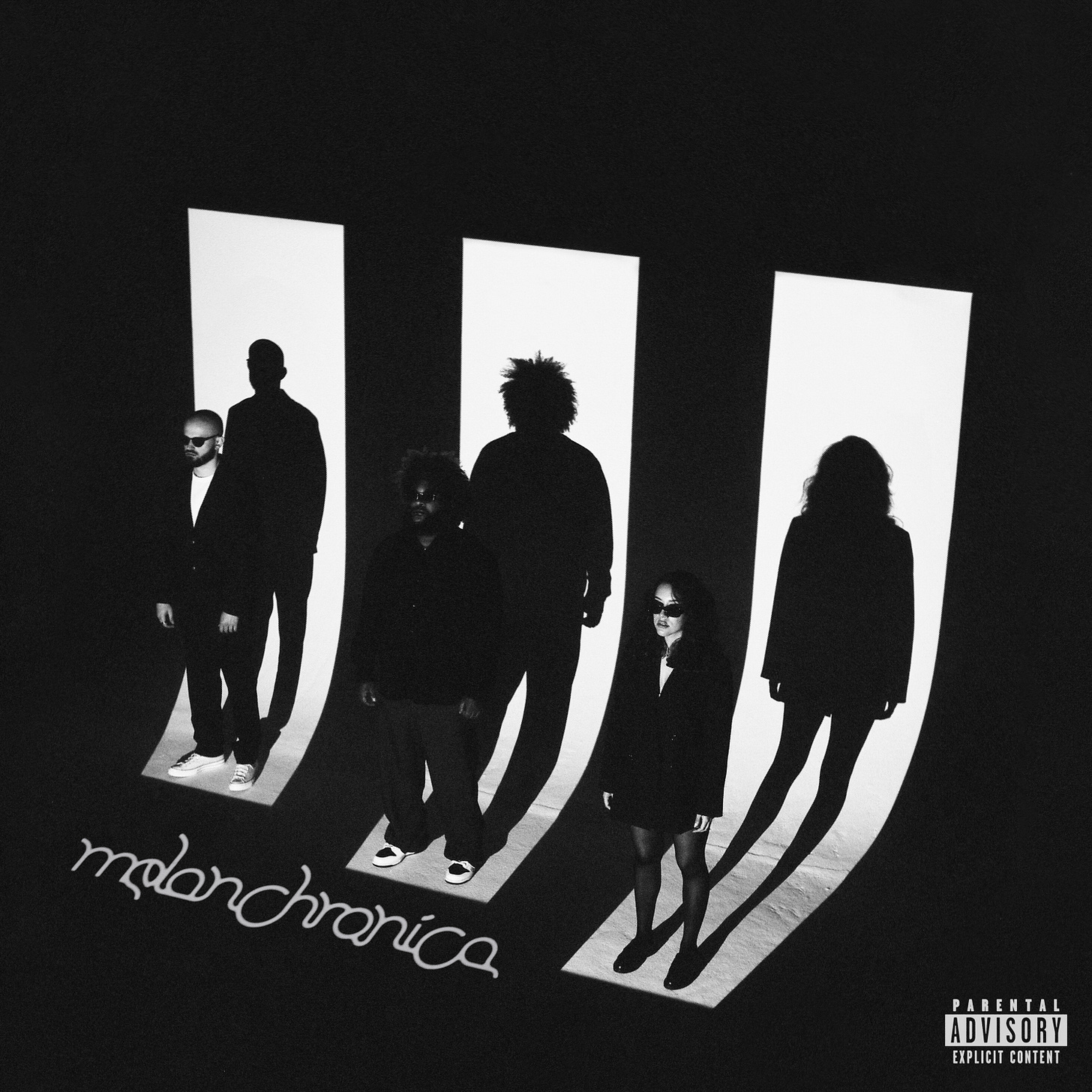

Bas & The Hics, Melanchronica

Roxane Barker describes Melanchronica as chronic melancholy balanced by sharp awareness of life’s dualities, and that declared goal guides every decision. “Out of Sight” introduces the theme with Bas weighing self-doubt against airy harmonies that refuse to dramatize despair. Ab-Soul joins “Norbit,” and the verses catalogue daily pressure while a subdued guitar loop keeps tension steady without swelling. “San Junipero” shifts beat texture during its second half so a plea to hold onto love can sit almost unaccompanied, spotlighting vulnerability. The reflection deepens on “Erewhon,” where Saba lists mounting bills that shadow ambition and underscores the record’s economic subtext. Short bridges such as “Roxanne’s Interlude” pause the forward motion just long enough to reset perspective without breaking cohesion. Bas and The Hics show that sitting with sadness can sharpen rather than dull creative clarity, offering comfort that feels earned, not decorative. — Reginald Marcel

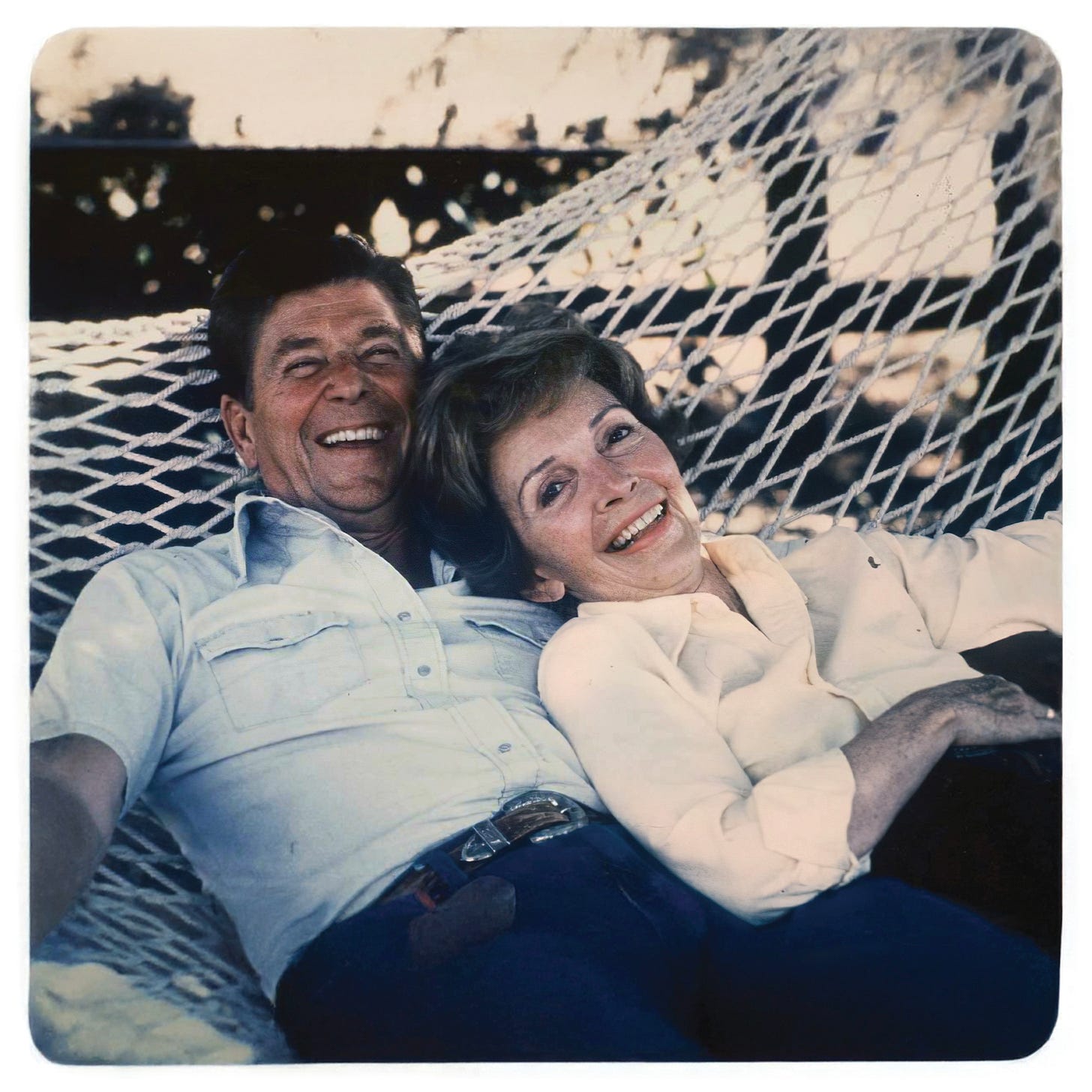

Apathy, Mom & Dad

Apathy builds this set on family stories and hometown snapshots, mixing pride with pointed critique. Soul-leaning samples and crisp drums frame verses that feel lived-in. For instance, “The Great Flood” brings Suave-Ski and Little Vic into a shoreline survival tale that sets the tone, “Shore Life” recalls summer ease through looping keys and relaxed hooks, and the title piece ties childhood memories to economic pressure from the Reagan years, tracing policy impact on household realities. Storytelling remains plainspoken and unsentimental. On “Blue Collar Scholar,” he and Slaine contrast classroom ambition with trade-work routine, underscoring work ethic over hype. Across “Put the Money In a Bag” and “Lee Harv,” he weighs hustle ethics against lingering doubt, keeping the language plain but pointed. As Apathy never slips on the mic, Mom & Dad reads like a self-reliance handbook wrapped in boom-bap grit. — Harry Brown

Sondae, Northstar

When Sondae sings “Open my eyes up to the beauty that remains,” the album’s devotional center locks into place. Early moments such as “Love Is Kind” and the radiant “Sun Rises” echo that pledge, trading ornate riffs for clear thematic repetition. Between gentle keys and lantern-glow drums, he repeats, “Lord, I need wisdom,” letting plain speech shoulder emotion instead of melismatic flourishes. Even when a bass groove nudges “We Rise and Fall” toward contemporary R&B, the lyric returns to mutual uplift, converting private stamina into communal resolve. Because Sondae avoids doctrinal jargon, seekers beyond church walls can enter the dialogue without translation. Throughout, prayer functions as conversation, proving intimacy can deliver grandeur without vocal theatrics. Northstar is a subtle guidepost, pointing towards steady self-improvement through deliberate, unvarnished praise. — Javon Bailey

Annahstasia, Tether

Across gentle plucked guitar and soft hand percussion, Annahstasia whispers questions about worth and endurance, letting silence speak as loud as pitch. During “Take Care of Me,” she sings, “I’m porcelain, sitting on your highest shelf, I’m gonna fall without your help,” laying out fear of abandonment in plain terms. “Unrest” shifts to relational tension yet leaves room for quiet reflection, while a soft string swell in “Be Kind” shows how she balances tenderness with unease. Guest harmonies surface briefly, then fade away, allowing the focus to remain on the first-person perspective. She will enable pauses between choruses, letting lines land without strain. Across the record, pacing stays unhurried and invites close listening. In “Believer,” she asks, “Can you be a believer?” while muted chords circle behind her. Because percussion rarely rises above a murmur, every breath shift feels intentional, keeping focus on lyrical nuance. Honesty takes priority over studio spectacle, and Tether carry monumental gravity when delivery and arrangement follow the same disciplined restraint. — LeMarcus

Lorde, Virgin

“This peace in the madness, over our heads, let it carry me,” Lorde sings at the very start of “Hammer,” and the line announces an album preoccupied with staying calm while everything tilts. Her writing keeps circling questions of womanhood and fame, especially on “Favourite Daughter,” where she frames body-image worries as blunt journal entries instead of poetic riddles. Club-leaning synth lines arrive courtesy of producer Jim-E Stack, yet the sounds stay uncluttered so each confession lands without ornament. “Clearblue” pulls a pregnancy-test brand into focus and broadens the record’s plain talk about sexual health and dependency. In “Current Affairs,” references to Brooklyn bridges and delis root her interior monologue in a new city, underscoring how place reshapes self-perception. A quieter stretch arrives with “Broken Glass,” whose sparse piano lets doubts linger rather than hurrying them away. On the final song, “David,” she recites a list of small promises to herself, showing resolve without dramatic fanfare. Taken together, the album showcases that candid detail and restrained production can carry pop ambition just as forcefully as stadium hooks. — Charlotte Rochel