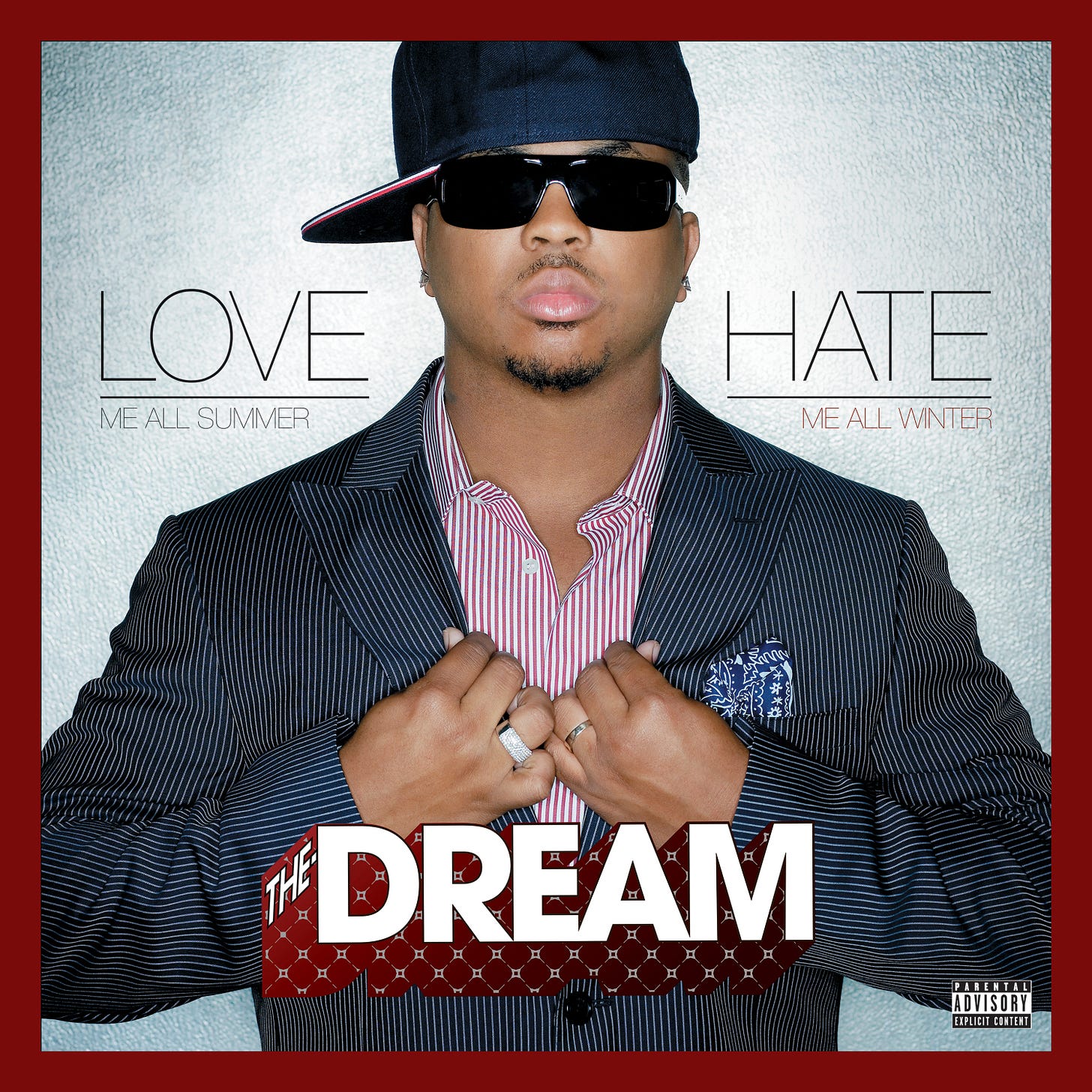

Love/Hate: The-Dream's Masterpiece 15 Years Later

To kick off his career in 2007, The-Dream released a stunning album. A cornerstone of technically proficient and emotionally expressive composition, it was a watershed point in merging Rap and R&B.

The motherly influence of Sam Cooke, Otis Redding, and Michael Jackson on Terius Nash's musical sensibilities was undeniable. For Nash, the fact that Michael Jackson was mortal was part of his allure, even if some of his admirers had never considered it until his death. Nash believed that artists were not immortal individuals whose only existence occurred onstage or in front of the camera. This was driven home not by Michael's death but by his mother's death in 1992 when Nash was only 15 years old.

Nash had never seen himself as a famous musician; all he ever wanted to do was compose masterpieces. Nash's brother Laney was an R&B veteran of the '90s who had worked closely with Babyface, L.A. Reid, and Jam & Lewis, and it was through him that Nash met Christopher Alan "Tricky" Stewart, a renowned writer and producer. When he needed to learn how to create, utilize an MPC, and handle everything on his own, Tricky was there to help. The two worked together to create a unique sound in the early 2000s that would dominate a sizable portion of pop radio for most of the decade.

Five songs co-written by Terius Nash were in the Top 30 of the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart when he released his debut album in the third-to-last week of 2007. However, only one of these songs was credited to him as a performer. These four songs were performed by Mary J. Blige (Just Fine), J. Holiday (Bed, Suffocate), and himself (Shawty Is a 10). Nash was given a creative license after another song he had a hand in, Rihanna's Umbrella, topped the Hot 100 for seven consecutive weeks six months previously. After becoming sick of song shopping and writing purely for singles, he met with L.A. Reid to pitch the notion of the-Dream as a solo artist. A few days later, he signed with Def Jam; the rest is history.

While Shawty Is a 10 is the more politically correct title, Nash's breakthrough hit, and the album's opener, Shawty Is Da Sh*!, is more accurate. I was kidding! Fabolous's endearingly awkward verse kicks off the song, with Nash delivering a support system of background "aye"s. Nonetheless, it is an excellent introduction to Nash's style, with the plunk of the doo-wop piano and the lovely falsetto. His voice isn't compelling, but it's the perfect conveyance for the catchy tunes he writes so that anybody can sing along. However, the most endearing aspect of that song is Nash's self-referential humor. He alludes to the Jay-Z track and how the rapper's winking motions reflect the song's themes onto the music. An insight into Nash's worldview is provided: one in which the lines between life and art blur, where composing music is as natural as falling in love, and where satisfying sexual encounters are the ultimate artistic achievement.

Maybe more than anything else, however, the ambition of Love/Hate has significantly impacted modern R&B. Beginning with I Luv Your Girl, a string of five songs that flow into one another is played. Transitions like this were not an afterthought but rather an integral part of Nash's writing process, which helped to create a seamless whole. With this album, the-Dream seems to be drawing a line between his background as a lyricist and his future as a solo artist. After the fading sounds of I Luv Your Girl, which include nighttime crickets, the sound of stilettos on a driveway, and the crank of a little red Corvette's engine, Fast Car, the most audacious Prince nod in Nash's discography to date, begins. Creative inspirations are badges of honor for Nash, who incorporates the snappy wit of Atlanta rap, the heady sensuality of Prince, and the rhythmic precision of Michael Jackson into his music. Love/Hate's suite of bouncy, seductive bops is concluded, and we're getting the realness as Fast Car fades into Nikki, its harmonies going from exuberant to desperate.

Nash's melodies slope downward on Nikki, the kick drums hit with an anguished thud, and he insists that he has moved on from the split. Contrary evidence may be found in the many layers of noise. Even in the early stages of a budding relationship, the chilly tone of She Needs My Love remains intact. The song has vocal harmonies buzzed up by martial percussion and static-filled synthesizers as he sings a defense of his relationship's territory. Nash’s love-sprung songs land as paranoid. It’s a post-breakup song, whether or not Nash meant it to be—a sensitive chronicle of navigating the world with your heart crushed. This song, the fifth and last of Love/Hate's rapid-fire sequence, maybe the most pivotal. Falsetto, on paper, is a plain sex jam—more straightforward in composition than the complicated tracks that precede it. It's also the sneakiest illustration of Nash's reflective songwriting method, in which the lines between romantic love, sexuality, and musical composition blur. The song’s core concept—that Nash’s stroke game can help his partner achieve high notes—isn’t the revolutionary creative terrain. Nash's ability to make his lady hit a falsetto is as much a hook construct as it is a throwback to his vocal range, which he adjusts on the fly to simulate a gently-exaggerated feminine tone, playing his voice like an eternally changeable instrument; here is where the song's beauty rests.

The album slows down for Playin' in Her Hair, a mid-tempo hymn for friends, lovers, and lovers-to-be that sounds like something Nash could write for Ciara, and Purple Kisses, another sweet, snappy love song, both Atlanta-centric and pro-woman. Nash's ability to write well and empathetically from a woman's viewpoint has been a remarkable aspect of his songwriting career. Nash didn't realize he could have such a viewpoint until he began composing songs; looking back, he can trace its roots. And it's not only because he grew up in a primarily female environment that makes him interested in seeing things from a female perspective. Nash's mother is honored in the album's conclusion, after 11 songs that explore many forms of love, desire, and sadness. Nash's first album's emotional center can't be found without Mama. Unlike anyplace else on the album, Nash's voice is modulated in the opening piano ballad, creating the sensation that his emotions are suffocating him. From the viewpoint of a mother singing to her kid, he uses his own human body as a reverberation chamber for his utterances. This is the essence of his creative empathy, the motor that propels his songwriting philosophy as a whole: through his songs, he strives to channel his mother's voice and express himself in the language she taught him.