May 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from billy woods to Kali Uchis, here are notable releases in May that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

In certain corners of the music fan community, this year isn’t as eventful compared to 2024 so far in terms of big-name drops (which, to be honest, is true). Tell these artists to step up. We managed to secure some drops from the majors that were rock-solid, but the indies were hitting and, unfortunately, not receiving the love they deserved. Not over here, though! That’s why you’re subscribed (and if you aren’t, please do so). Editors at Shatter the Standards arranged this list in alphabetical order. We hope the second half of 2025 improves.

José James, 1978: Revenge of the Dragon

José James cut the entire set to two-inch tape inside Dreamland, a converted church whose wooden rafters trap cymbal spray and ambient hiss, so the record breathes like a crowded club rather than a DAW grid. BIGYUKI’s analog synths fizz against Jharis Yokley’s cracked-rim snare while a three-horn frontline of Takuya Kuroda, Ebban Dorsey, and Ben Wendel punches lines that feel lifted from a Shaw Brothers soundtrack. “Tokyo Daydream” drapes that brass over a rubber-band bass ostinato, then slips into double-time handclaps that evoke neon alleys at midnight. The Michael Jackson cover “Rock With You” slows to half-speed, James stacking his voice into woozy harmonies while a dubbed-out clavinet wobbles beneath muted trumpet. “They Sleep, We Grind (for Badu)” filters a clav groove through tape echo, echoing its mantra-like hook across speaker cones until it feels more ritualistic than a song. Original “Rise of the Tiger” rips forward with fuzz bass and kung-fu dialog samples, paying tribute to James’s own martial-arts practice. “Last Call at the Mudd Club” ends on a bent tenor-sax scream that fades into the studio’s natural reverb, leaving only creaking floorboards and tape hiss as the lights cut. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Reuben James, Big People Music

The British pianist’s songwriting matures into expansive, chorus-rich neo-soul that nods to Donny Hathaway and late-period D’Angelo. Opener “Elders” breaks in on a stacked gospel-choir vamp, James’s falsetto gliding above clipped wah-guitar. Horn arrangements bloom across the record, arranged as counter-melodies rather than mere stabs; “Sunset in Soho” features a flugelhorn line that mirrors the vocal melisma on its final refrain, giving the song a circular symmetry. The piano remains the anchor, block chords in the low register, right-hand trills recalling Oscar Peterson, but the rhythmic emphasis sits firmly in the pocket, courtesy of swung rim-shots and hand-clap overdubs that keep each hook buoyant. — Jamila W.

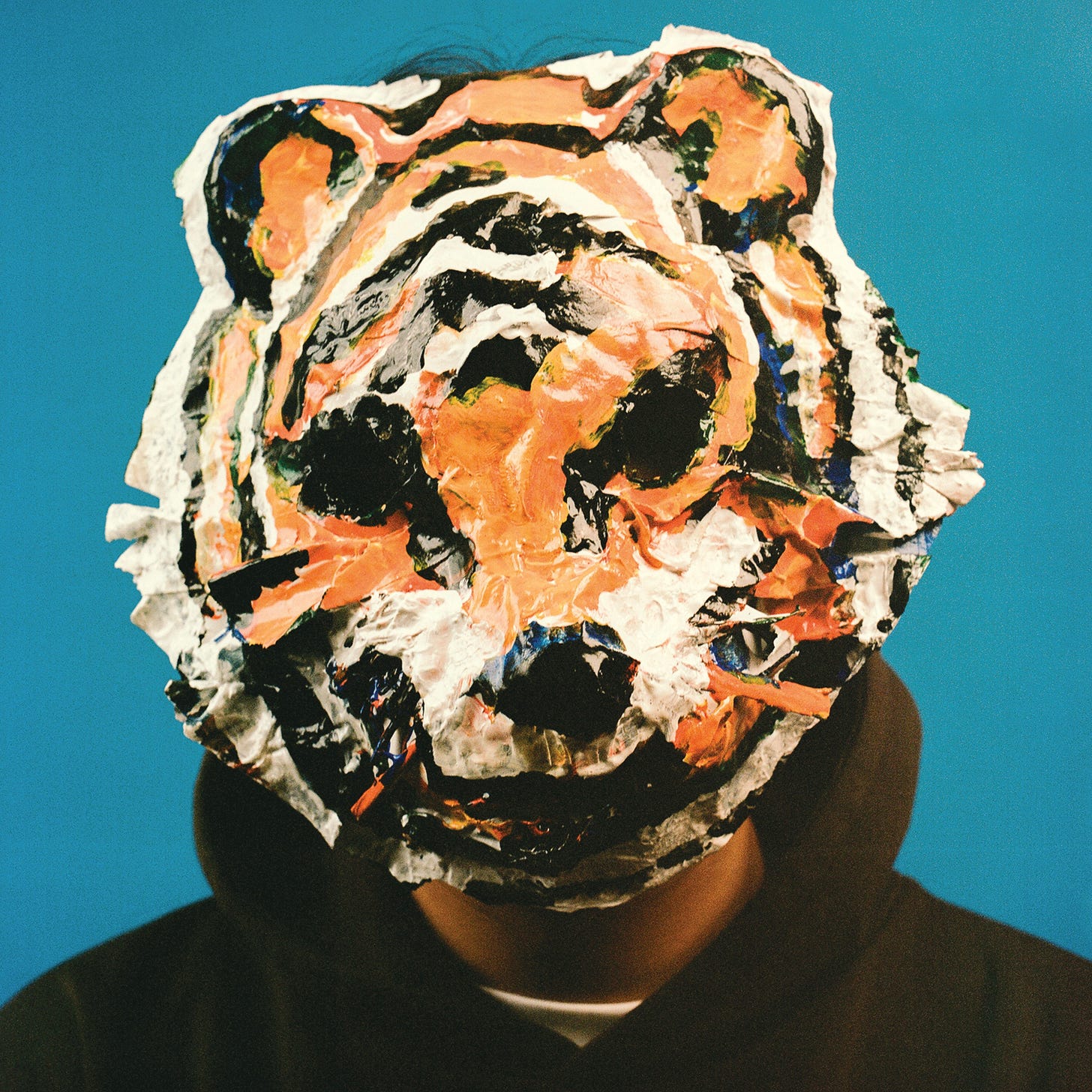

Aesop Rock, Black Hole Superette

Aesop Rock takes sole control of the beats, stitching tight drum grids to clipped keyboard hooks and placing speech samples where most rappers would drop ad-libs. “Secret Knock” introduces a habit of pairing everyday details—door codes, loyalty cards—with broad questions about routine and privacy, while “1010WINS” lowers the percussion so Armand Hammer can volley terse headlines that emphasize information overload. The melodic outline stays clear even when synth layers multiply, which lets Aesop’s dense word clusters remain intelligible without resorting to obvious hooks. “Checkers” pivots on a piano stab that cuts against a shortwave-radio squall, and “Snail Zero” turns a loose bass line into the backdrop for wry observations about slow growth. Open Mike Eagle slips into “So Be It,” delivering a dry counterpoint that matches the album’s understated tone. A short run of instrumentals midway through provides breathing room, each built from a single motif that fades before it overstays. Throughout the hour-plus runtime, city sounds and consumer chatter never feel tacked on; they serve as reference points that keep the more abstract lines grounded. — Harry Brown

Your Grandparents, The Dial

The trio stretches a single metaphor—the telephone—as a portal through memory, desire, and altered consciousness. The set opens with the title piece, a stuttering break-beat and woozy Rhodes that bleeds directly into “All Dem Times,” where rumbling sub-bass underlines stacked harmony lines reminiscent of late-‘90s L.A. neo-soul sessions. Mid-sequence, “Tea Lounge/Blossom” unfurls in two movements: first a brittle drum-machine shuffle, then a flute-laced psychedelic bridge featuring singer Iyana that recalls Shuggie Otis’s liquid guitar phrasing. The trio’s rapper–crooner interplay peaks on “Hypnotized,” trading sing-song cadences with Belgian duo blackwave. over a clavinet riff that could have spun out of George Clinton’s vault. Closer “Down” rides a chopped-and-screwed chant toward silence, completing a cycle that feels like hanging up the cosmic receiver. — Reginald Marcel

Chuck D, Enemy Radio: Radio Armageddon

Chuck D wields his baritone the way Coltrane used sheets of sound—layered, unrelenting, and always aimed at a higher civic purpose. Over breakbeats that crunch like smashed radios and shards of distorted acid-rock guitar, he re-stacks the Bomb Squad’s collage aesthetic into a leaner but no less combustible broadcast that ricochets between scowling funk riffs and proto-punk thrash. Cuts such as “Black Don’t Tread” and “Rogue Runnin’” bolt scratch choruses to thrumming bass, framing verses that rage against algorithmic misinformation and voter suppression with the same urgency he once leveled at Reagan-era racism. Yet the record is hardly a nostalgia trip: on “New Gens,” he cedes the spotlight to Stetsasonic’s Daddy-O and a chorus of younger MCs, threading old-school mic-command into a rolling drill-adjacent cadence that argues cross-generational solidarity is the new radical gesture. Across the album’s “station breaks,” hard-panned sirens, Black radio idents, and shortwave static create the illusion you’re spinning a dial through the apocalypse—only to land, again and again, on a voice that refuses to yield. — Phil

PinkPantheress, Fancy That

PinkPantheress turns brevity into a high-wire act of detail. “Illegal” kicks off with the synth-arpeggio from Underworld’s “Dark & Long” before diving into rattling jungle breaks, then suddenly shifts to a four-on-the-floor thump for a euphoric final twenty seconds. Samples flash by like TikTok swipes—Basement Jaxx strings underpin “Girl Like Me,” while a Nardo Wick vocal chop becomes a stoned call-and-response in “Noises,” each reference treated not as nostalgia but as brick in a new soundhouse. She is sharper and funnier than ever: “Romeo” weaponises a breezy two-step groove to deliver a pansexual kiss-off—“You can fall in love with boys and girls and in between”—that sounds like pure bubble-gum until the line lands. By the time closer “Tonight” melds emo-guitar chug with speed-garage drums, the mixtape feels like a pocket-sized universe where early-2000s MySpace angst, Y2K mall-pop kitsch, and hardcore-continuum futurism dance without hierarchy. — Oliver I. Martin

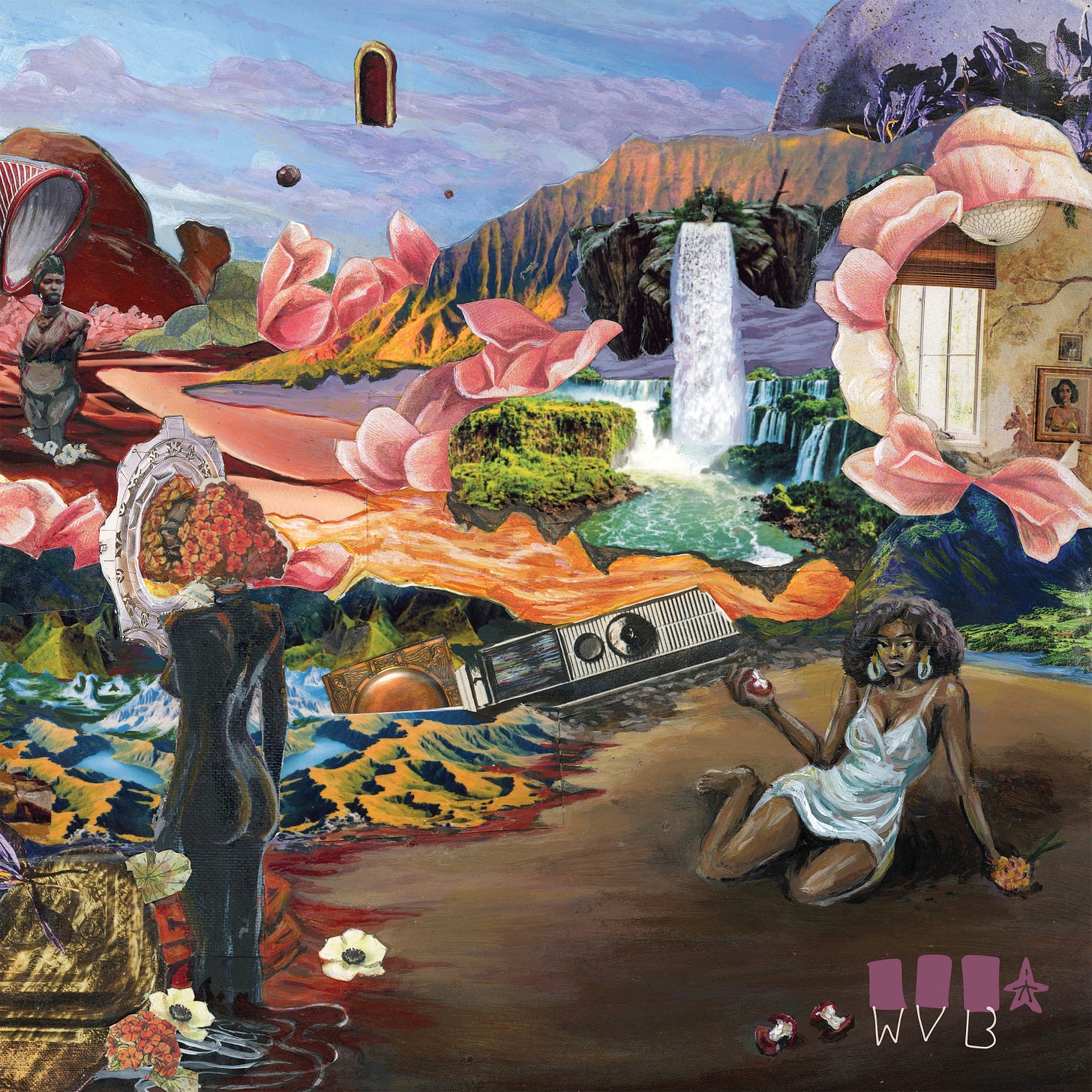

Brandon Woody, For the Love of It All

Woody’s trumpet tone sits somewhere between Clifford Brown’s caramel warmth and Christian Scott’s breathy edge, but his compositional sense is firmly of the present: trap-lilted hi-hats coexist with modal piano clusters and snatches of spoken-word prayer. The album is structured like a church service turned block party—opening fanfare, communal affirmation, ecstatic peak, contemplative benediction. Upendo, his long-running quartet, locks into polyrhythms that reflect Baltimore’s go-go legacy even as synth textures nod toward cosmic-jazz futurism. On “Never Gonna Run Away,” Woody quotes “Lift Every Voice and Sing” before vaulting into a double-time solo that feels like an asphalt sprint through North Avenue at dusk. He refuses the jazz-world trope of geographic migration, choosing instead to root the music in the city that raised him; the result is a record that radiates place-based love without turning parochial, achieving universality through hyper-local detail. — Phil

Mourning [A] BLKstar, Flowers for the Living

The Cleveland collective’s newest is equal parts funeral dirge and liberation hymn. Opener “Stop Lion 2” fuses distorted bass drone with a field-recorded Baptist shout, interrupted by a spoken-word salvo from Lee Bains that sounds like Gil Scott-Heron channeled through post-punk megaphone. Elsewhere, “Letter to a Nervous System” layers tape echo on dour trumpet lines, evoking the echo-chamber anxiety of the album’s title. Yet hope persists: closer “88 pt.” hinges on a modal, Major-7th guitar vamp that brightens each chorus, suggesting blossoms pushing through concrete. Multiple lead vocalists trade lines like communal testimony, transforming grief into collective propulsion. — Brandon O’Sullivan

billy woods, Golliwog

When Golliwog opens with “Jumpscare” with warped horns and tape hiss, it sets a claustrophobic mood that never fully lifts. billy woods raps in dense, imagistic bursts, stacking references to colonial history, horror cinema, and everyday micro‑aggressions until the lines feel like overlapping newspaper clippings. Throughout the album, the production pivots between dusty jazz loops and abstract sound design. “Star87” floats over a detuned vibraphone riff that keeps slipping out of key, while “Misery” uses a brittle guitar figure that fractures under heavy reverb. Guest spots amplify the kaleidoscope; Bruiser Wolf’s off‑kilter drawl on “BLK Xmas” adds sardonic humor, Despot’s surgical precision on “Corinthians” sharpens the track’s edges, and ELUCID appears multiple times, his voice acting as both mirror and foil to woods’ weary baritone. The middle stretch (“Waterproof Mascara,” “Counterclockwise,” “Pitchforks & Halos”) digs into paranoia, with drums that drop out unexpectedly, forcing the listener to cling to woods’ internal rhythms for footing. Near the end, “Lead Paint Test” and “Dislocated” widen the sonic palette with industrial clangs and ghost‑choir samples, pushing the project into near‑apocalyptic territory. Despite the heavy subject matter, there is a sly playfulness in woods’ rhyme schemes; multisyllabic patterns tumble into sudden blunt phrases, mirroring the album’s thematic tension between performance and painful memory. — Phil

Wretch 32, Home?

Wretch’s writing has always balanced nimble wordplay with confessional heft, but here the stakes feel existential. The opening track juxtaposes news-clip sirens with a choir that could have drifted in from Brixton’s Pentecostal churches, underscoring his question: Can a nation that polices your very breath ever be “home”? Over minimalist, hi-hat-heavy production, he threads Jamaican patois into North London argot, treating language itself as a contested post-colonial terrain. Mid-album standout “Diaspora Dinner” samples clinking cutlery and dub bass, turning the simple act of sharing food into a metaphor for generational memory. The project ends not with resolution but with a question-mark bass-drum thud, Wretch whispering, “Maybe I’ll find it in my son’s accent,” a line that lingers long after the music fades. — Ameenah Laquita

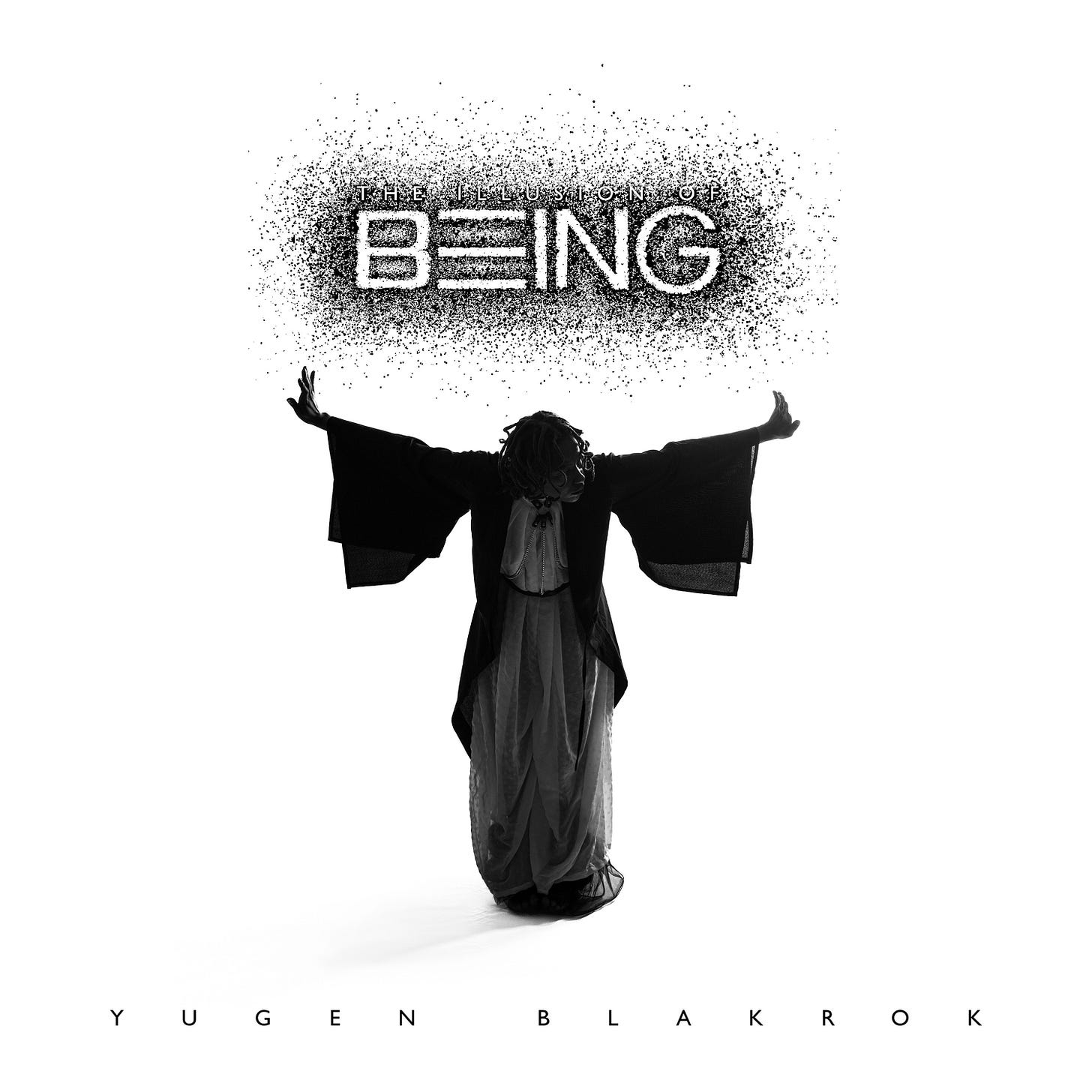

Yugen Blakrok, The Illusion of Being

Yugen Blakrok’s second full-length since 2019 opens in near darkness, “Mesmerize” pacing over murky analog bass and vinyl crackle while Loudmic’s scratch work circles like a vulture. Her delivery is measured, almost meditative, yet every internal rhyme detonates on the down-beat, turning the track into a slow-burner that refuses the dopamine rush of contemporary trap templates. Throughout, the emcee pokes at certainty itself—“Absolute truth is just a myth in this reality/Like the gender of God…” she spits on “Earthlinguist,” teasing cadence until the beat seems to hold its breath. Kanif the Jhatmaster’s beats avoid maximalism, favoring negative space and low-pass grit that recall Company Flow’s early tectonic rumble more than glossy modern boom-bap. Cambatta turns “Tessellator” into an occult cypher of syllable flips while Sa-Roc’s razor-sharp counter-flow on “The Grand Geode” feels like two griots carving hieroglyphs into the same stone in real time. A broken-time snare pattern jitters beneath guitars and swirling synth arpeggios while Blakrok spits “I bend light around my name,” collapsing cosmic physics into street-corner bravado. Rather than a victory lap, the fade-out opts for unresolved chords, implying that transcendence is a process, not a destination. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Lido Pimienta, La Belleza

Pimienta’s nine-movement suite begins with “Overturn,” a miniature overture where Gregorian-tinged choir lines hover above bowed vibraphone clusters, nodding to early-music repertoire yet resting on a 3/2 Afro-Caribbean pulse that never quite lands on the one. The contrast sets up the record’s guiding question: how do you reconcile the Catholic requiem tradition with the polyrhythms of Colombia’s Wayuu coast without sacrificing either one’s spiritual heft? She tackles that dilemma head-on in “Ahora,” framing her vocals in close-miked whispers before exploding into open-throated melisma over brass stabs arranged by Owen Pallett and the Medellín Philharmonic. “La Belleza” ends not with a triumphal coda but with “Busca La Luz,” a brief, almost folk-song epilogue sung in hushed unison with a children’s choir. The shift from philharmonic grandeur to porch-side intimacy underscores her thesis: beauty lives in the cracks between institutional polish and communal memory. What makes the record so disarming is its refusal to treat the orchestra as an ornamental element; instead, Pimienta draws symphonic tradition into dialogue with maracas, whistles, and Andean flutes, until the hierarchy evaporates. — Charlotte Rochel

Jamael Dean, Oriki Duuru

Dean sat at a grand piano at 2220 Arts + Archives, with no written program, allowing a sixty-minute improvisation to flow uninterrupted; the Yoruba title translates loosely as “piano poems,” underscoring how invocation, rather than virtuoso display, guides the music. “On Green Dolphin Street” appears in phantom outline, its harmonic skeleton reharmonized into quartal voicings, while “Tin Tin Deo” rides cross-rhythms that nod to its Afro-Cuban roots without locking into clave. Originals like the two-minute “Rise & Fall” incorporate small melodic cells—sometimes just three notes—into spiraling left-hand ostinati, demonstrating Dean’s mastery of tension and release. — Murffey Zavier

Don Glori, Paper Can’t Wrap Fire

Multi-instrumentalist Gordon Li assembles a rotating sextet whose horns trace Ellington-school voicings while the rhythm section locks into Eddie Palmieri-tight montunos. “Dusty Shelves” foregrounds congas and cowbell before dissolving into Fender Rhodes clusters—proof of Li’s affinity for early-‘70s CTI fusion, but the pocket remains resolutely modern, closer to Hiatus Kaiyote’s elastic swing than straight revivalism. Throughout, he leans into vocal choruses—wordless at first, then bursting into gospel call-and-response on “Black Flame”—a stylistic expansion from his previous, mostly instrumental catalog. The title track’s final two minutes stack tape-looped horns atop a drum-and-bass rhythm, suggesting that even Don Glori’s most soulful gestures refuse complacency. — Randy

MIKE & Tony Seltzer, Pinball II

On the surface, this sequel feels louder and brasher than the smoked-out haze that earned MIKE a cult following, yet its core remains diaristic. Tony Seltzer’s drums snap like broken arcade bumpers over chopped guitar squeals that crib from horror-score dissonance and litefeet’s whiplash kinetic swing, giving MIKE permission to rap with a bared-teeth confidence he once reserved for private notebook entries. “WYC4” inverts hustle-culture clichés by framing success as an act of spiritual hygiene, while “#71” stacks claustrophobic phrases into a mantra that collapses into a beat switch worthy of a slasher jump-cut. When Earl Sweatshirt crashes “Jumanji,” the song turns into a cypher about survivor’s guilt that’s both playful and bruised. The album’s emotional ballast, though, is “Chest Painz,” where MIKE’s voice fractures under the weight of a lost friend’s voicemail, proving that vulnerability can coexist with swagger without cancelling either out. — Nehemiah

Tanika Charles, Reasons to Stay

Tanika Charles sings like she’s opened every wound just wide enough for the groove to cauterize it. Her fourth LP trades previous rom-com heartbreak narratives for familial fault-lines, stacking Chi-Lites-style string swells and clipped hi-hat shuffles against lyrics that name-check abandonment, reconciliation, and inherited shame with unflinching clarity. “Don’t Like You Anymore” drapes smoky B-3 chords over a head-nodding pocket, her phrasing dipping into husky low notes before vaulting into a trembling melisma that cracks exactly where the story does. Producer Scott McCannell and mixer Kelly Finnigan infuse every rim-click and tambourine shake with analog hiss and ribbon-mic saturation, lending mid-tempo burners like “Talk to Me Nice” the warm, vintage sound of a lost 1973 acetate without ever sounding like a costume. When Clerel’s smoky tenor enters on the Gamble-and-Huff-tinged “Win,” the arrangement briefly slips into woozy psychedelic gospel before returning to its neo-soul core—a reminder that Charles, even in her most vulnerable confessions, never lets the pocket drift. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Milena Casado, Reflection of Another Self

Spanish trumpeter Milena Casado’s debut is less a set of tunes than a suite of interior monologues rendered in sound. Co-produced with Terri Lyne Carrington, the record cross-fades brushed-snare swing, open-horn motifs, and harp glissandi into vapor-hiss electronics and sampled family conversations, mapping trauma and self-reclamation onto a dreamlike jazz-scape. “O.C.T.” tilts a muted trumpet solo over Val Jeanty’s turntable textures, letting fractured beat-snippets glitch beneath harmonic minor progressions that evoke late-‘60s Miles while sounding unmistakably 2025. Three brief “Introspection” interludes splice whispered Spanish questions through reversed cymbals, creating breathing room before the quartet surges back with modal burners including “Resilience,” where Lex Korten’s piano clusters chase Casado’s growling upper register until both resolve on a luminous chord the composer calls “miracle major.” The closing featuring Meshell Ndegeocello’s bass harmonics and Brandee Younger’s cascading arpeggios lands like morning sun after a night of reckoning—proof that the album’s title isn’t rhetorical but a sonic ritual of becoming. — Imani Raven

Knowledge the Pirate & Roc Marciano, Round Table

Roc Marciano’s loops here barely clear the noise floor—hushed Rhodes phrases, brittle snare taps, leaving Knowledge’s gravelled baritone to fill the frame. Opening salvo “Eating Etiquette” reimagines fine-dining manners as codes for dope-game discretion; lines about “forks and knives” resurface later as metaphors for friends who cut both ways. The lone posse moment, “The Outfit,” finds Roc himself stepping from behind the boards to swap weary boss talk in eight-bar bursts, the pair sounding like chess partners mid-match rather than rivals. Across the album Knowledge revisits maritime lore—“Addicted to Danger” compares a cracked hull to a bruised ego, and closes on “Receipts,” a recounting of debts paid in blood that fades under creaking ship-rope samples, tying the crime narratives back to the title’s code of honor. — Javon Bailey

Kali Uchis, Sincerely,

Framed as a box of unsent letters, Sincerely threads bilingual confessionals through slow-motion soul arrangements whose edges blur like ink on vellum. “Heaven Is a Home…” eases in with Sunday-service organ before cavernous half-time drums and stacked choir harmonies suggest the solitude of prayer rather than the pomp of gospel. “Sugar Honey Love” lifts a doo-wop progression then melts it beneath Mellotron flutes while Kali Uchis sings, “You put the blood back to my heart,” an image that turns romantic sweetness into literal resuscitation. Mid-sequence ballad “For: You” floats on vinyl crackle and muted strings; the vocal barely rises above a whisper, transforming grief into a lullaby instead of a lament. Volt-switch “Daggers!” slams distorted synth-bass against break-beat clatter, her doubled vocal riding inside the beat rather than above it, as if anger itself is trapped in that buzzing low end. “Breeze!” resolves the cycle with brushed drums and nylon-string guitar that fade into room tone, mirroring the way loss never entirely disappears—it just becomes another current of air moving through the day. — Charlotte Rochel

Rome Streetz & Conductor Williams, Trainspotting

Conductor Williams supplies sample-centric beats marked by mid-tempo drum hits and brief horn chops, giving Rome Streetz a stable runway for intricate rhyme chains. “Andre Agassi” introduces terse internal patterns that parse risk and reward without ornamental slang. Method Man’s verse on “Ricky Bobby” floats over a sparser arrangement, highlighting generational contrasts in delivery while keeping the focus on cadence. Jay Worthy steps into “10 Toes” with a smoother drawl that never softens the grit of Rome’s syllable stacks. Short interludes, such as “Connie’s Revenge,” reset the ear, each built from a single loop that drops out before it can blend with the main tracks. When the theme shifts to industry pitfalls on “Rule 4080,” Conductor pares the beat back to a hi-hat pattern, letting contract-law references land without distraction. A late track called “Electric Slide” introduces a bright keyboard figure, offering tonal lift before the sequence settles back into weightier textures. The partnership succeeds because neither artist overplays; space in the mix carries as much attitude as any rhyme. — Reginald Marcel