Milestones: Adventures In Paradise by Minnie Riperton

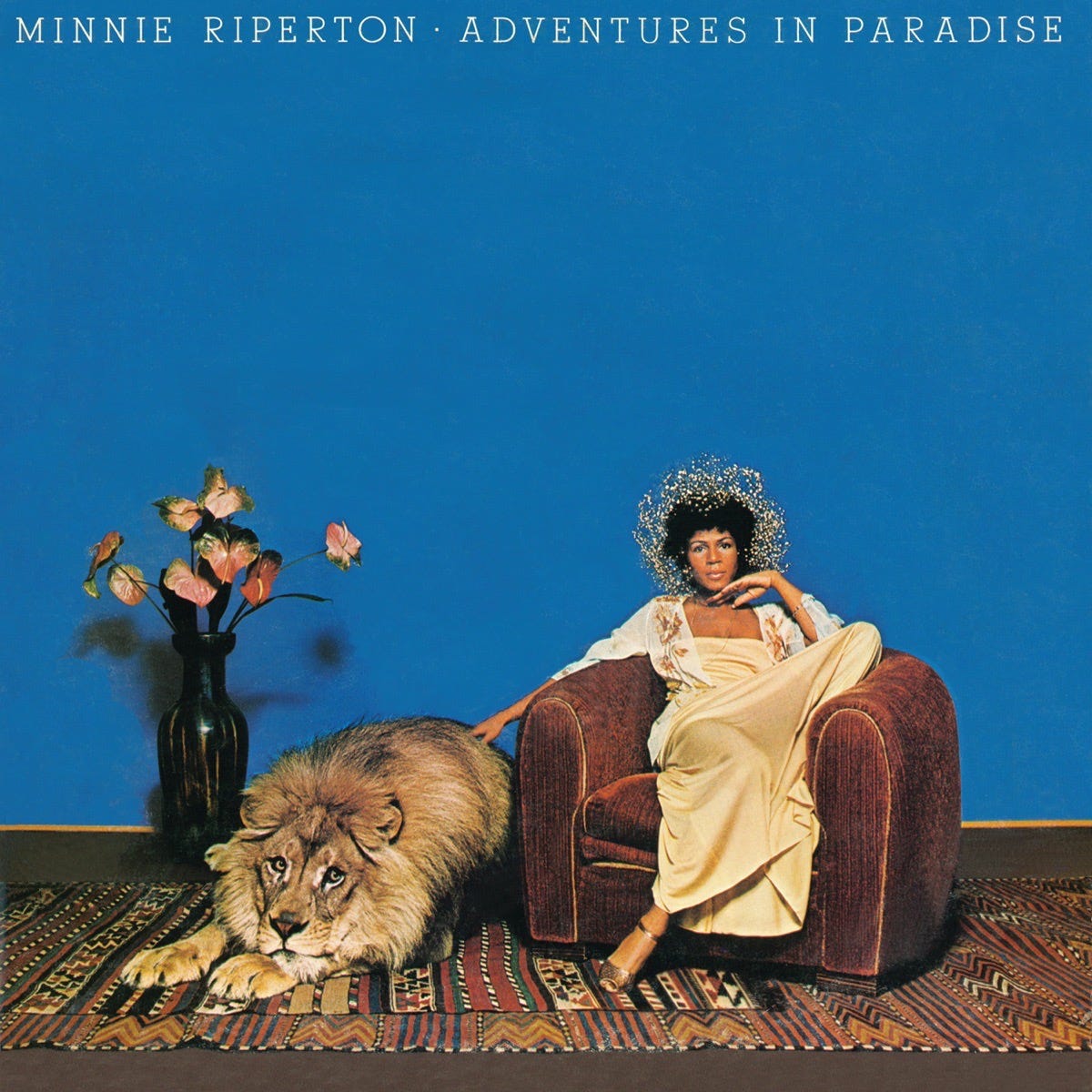

The lion on the cover, tamed yet potent, is the perfect emblem: Riperton had no interest in declawing emotion—only in showing that ferocity and tenderness might share the same golden pelt.

Minnie Riperton opened Adventures In Paradise by inviting us into a sound-world at once pastoral and carnal, and every element surrounding the 1975 LP feels in service to that tension between innocence and adult intimacy. The visual cue came first. Norman Seeff photographed Riperton cross-legged in a linen halter dress, her back arched toward the sun and her palm resting on the mane of a full-grown lion. The tableau suggested biblical tranquility, but the session’s aftermath became legend when a different lion, hired for a television commercial the same week, lunged at Riperton without warning; only the trainer’s quick sedative prevented catastrophe. She kept the calmer portrait for the sleeve, insisting that serenity beat spectacle, even as bruises were still blooming beneath the fabric.

That refusal to flinch defines the music as well. With Stevie Wonder busy shaping Songs In the Key of Life, Riperton and her husband-collaborator Richard Rudolph drafted producer Stewart Levine and a small orchestra of Los Angeles session royalty: Larry Carlton to arrange and conduct, Joe Sample on keyboards, the Crusaders’ rhythm cohort, drummer Jim Gordon, reed specialists Jim Horn and Tom Scott, and, glistening atop the string section, harpist Dorothy Ashby. These players recognized that Riperton’s soprano, capable of vaulting from a dusky mid-range into an F-sharp at the edge of audibility, didn’t need to be framed in velvet; it required open air. Consequently, the record lives in jazz-soul half-light: more languid than Perfect Angel, more ruminative than the disco-tilted Stay in Love that would follow.

“Baby, This Love I Have” sets the emotional compass. Over Sample’s Fender Rhodes clusters and Gordon’s brushed 4/4, Riperton phrases the opening couplet—“Things I say and do may not come clear throug/My words may not convey just what I’m feelin’”—in a near-conversational rubato, then pivots to a head-voice ascent on “Baby, I’m tryin’ to show you that I care,” letting the final vowel float above Sample’s Rhodes smear like a gull riding updrafts. Where my earlier pass misrendered the hook, the real refrain grounds the song in affirmation, not torment: “And all I know is true/Is this love I have for you.” That declaration, feather-light yet unequivocal, sets the album’s baseline: sensuality as a fact to be explored, never apologized for.

Where Perfect Angel had begged the radio to embrace love as a lullaby, Adventures asks for something more grown: a love that knows the geography of the body without surrendering the mind’s curiosity. Nowhere is that clearer than in “Inside My Love,” the Leon Ware co-write that still divides listeners. Ware based his lyric on “Two people, just meeting/Barely touching each other,” then Riperton slides into the more cryptic second verse—“Two strangers, not strangers, only lacking the knowing.” Her question, canonised as radio taboo—“Do you wanna ride inside, my love?”—lands on an elongated melisma whose outward sweetness hardly masks its invitation. She punctuates each chorus with a whistle-register pirouette, effectively spiralling the physical longing beyond language into pure tone. Ware later said he borrowed the imagery from a preacher’s call to “come into the house of the Lord,” and Riperton’s performance honours that double duty: sacred and erotic collapse into the same breath, reminding listeners that metaphors of entry have theological roots as well as libidinal ones.

“Feelin’ That Your Feelin’s Right” turns desire outward, toward motion and optimism. Over Carlton’s syncopated guitar and Gordon’s ride-cymbal flicker, Riperton toggles between chest voice and a sunny head tone, stitching together lines that celebrate emotional reciprocity: “All at once I found the perfect feeling/I can’t believe what seemed so hard comes so easily… It came all over me.” Her rhythmic placement is micro-subversive; she sings slightly behind Sample’s back-beat, making ease itself audible. The effect anticipates neo-soul’s later fascination with time-bending around the pocket.

One track later, “When It Comes Down to It” answers that buoyancy with a blues-inflected reality check. Riperton drops into chest register to warn, “All you high-falutin’ ain’t worth nothin’ when you’re old,” before the chorus tightens to the moral: “When it comes down to it, love will get you more than gold.” The shift from gossamer whistle notes to earthy alto proves how deliberately she wields timbre: tonal warmth becomes the mirror of lyrical pragmatism.

Side one closes with “Minnie’s Lament” and “Love and Its Glory,” a diptych that shifts the album’s gaze from bodily discovery to narrative empathy. “Minnie’s Lament” is a quasi-spiritual; over a descending chromatic line, Riperton mourns unnamed losses, her whistle register thinning to near-silence as though grief itself were consuming the oxygen. Immediately afterward, “Love and Its Glory” reframes heartache through the eyes of an adolescent: the heroine, Maya (yes, named for Riperton’s young daughter), defies her parents to marry a forbidden love, only to be rescued at the altar by that very partner. The story could read as melodrama, yet the singer’s marvel is restraint. She colors phrases with gentle vibrato, letting Ashby’s harp and Sid Sharp’s strings do the weeping, so when the couple triumphs, it feels earned rather than inevitable.

Joe Sample’s co-title track “Adventures in Paradise” opens the second half by re-centring fantasy. The groove fuses samba-inflected hi-hat with a rubbery bassline; atop it, Riperton builds a wordless vocal coda—ascending triads that crisscross in call-and-response with Tom Scott’s soprano sax—turning paradise into an aural place that seems to rise and vanish in real time. That sense of impermanence haunts “Alone in Brewster Bay,” that reins the fantasy back to coastal winter, its lyric conjuring “snowflakes fly” and “geese out honkin’ on the bay” as markers of solitude. Here, too, my earlier summary overstated a line about “dreams” that never appears; what the song actually repeats is a confession of fragility that Riperton sings with half-closed vowels, turning the lament into breath on glass.

“Simple Things” restores warmth via gospel-bright piano and almost nursery-rhyme scansion. Instead of the line I mis-remembered, Riperton actually centers the philosophy of Simon Says–style mindfulness: “If Simon says ‘Be glad today’/I surely do what Simon say.” The humor of that syntax underscores the point that contentment can be childlike without being childish. And when Carlton’s guitar nudges the modulation, Riperton glides up the scale, stitching whistle-tone grace notes between syllables the way trumpeter Bobby Hutcherson might slide grace notes between mallet hits. The finale, “Don’t Let Anyone Bring You Down,” seals the album’s thematic circle. Centered on a resolute piano motif, it becomes a benediction: Riperton’s tone alternates between motherly assurance and quiet self-talk, especially in the final whispered aside, “I hope I’ve made you feel good.” Instead of the ecstatic abandon of “Lovin’ You,” she chooses reassurance—a subtle but profound shift from personal bliss to communal uplift.

While creating this LP, Riperton was keeping a private vigil: a lump discovered in her breast during promotional rounds led to a 1976 mastectomy and the public disclosure of her cancer diagnosis on The Tonight Show the following year. Listening back, you can hear the precarity of that moment infusing the work; the record’s alternating tones of delight and foreboding feel less like stylistic variation and more like honest documentation of someone who knew paradise could be lost without notice. Yet there is no trace of defeat in the performances. Every whistle note, every sotto-voce gasp, every word elongated or compressed, argues for a life lived at maximal expressive range.

Riperton’s technical vocabulary remains astonishing. She uses the whistle register not as a novelty, but as a narrative device, signaling vulnerability in “Minnie’s Lament,” ecstatic surrender in “Inside My Love,” and comedic release in improvised codas that fade into laughter rather than applause. Her head-voice transitions are frictionless, and her breath control lets her float phrases over measures others would subdivide. But perhaps more radical is her rhythmic daring. On “Baby, This Love I Have,” she sings slightly behind the beat, making pleasure sound luxurious; in “When It Comes Down to It,” she clips ahead, as if urgency could avert heartbreak. These time games foreshadow later singers, from Mariah Carey to Bilal, who bent meter to fit emotional nuance.

Personnel choices reinforce those rhythmic subtleties. Carlton’s guitars rarely solo; instead, they stitch chordal filigree around Riperton’s syllables, echoing her shape-shifting lines. Sample plays keyboards with an arranger’s ear for space, leaving entire half-measures bare so that a single vocal inhale becomes a percussive event. Ashby’s harp triggers glissandi timed to Riperton’s breath, turning inhalations into spark trails. Even Gordon, better known for rock heft, dials back to brushes and rim-clicks, framing the singer’s quietest coos. The cumulative effect is chamber-soul: intimate yet luxurious, every instrumentalist listening for the micro-pause before a phrase so they can enter like moonlight under a door.

Themes of sensuality, positivity, and fantasy do not appear as separate lanes but as spokes radiating from a center of self-possession. Riperton never treats sensual exploration as antithetical to moral uplift; the erotic and the affirmative coexist in the same lyric, often the same breath. Consider “Inside My Love”—her voice flickers between invitation and prayer, so the plea to be entered sounds indistinguishable from an appeal for spiritual communion. Likewise, “Simple Things” frames household rituals as pathways to transcendence, while “Adventures in Paradise” locates fantasy not in outer space but within the chords of a Fender Rhodes. Positivity here is not denial of hardship; it is the conscious generation of light in a body already carrying darkness.

That duality became achingly literal as her cancer advanced; yet rather than overshadow the record, knowledge of her illness casts its grace in sharper relief. She was thirty-eight months from her death when these sessions wrapped, but the music insists on futures—future embraces, future adventures, future mornings. Her last whispered question, “Did I make you feel good?” lands now as both gentle query and final thesis: that the artist’s highest calling might be to leave the listener lighter than she found them.

Adventures In Paradise never chased the crossover blitz of “Lovin’ You,” and radio censors balked at its most explicit single, but commercial metrics feel irrelevant beside the album’s quiet influence. It taught generations of singers that virtuosity could be intimate; it proved that black feminine sensuality could express itself in its metaphorical language; and it modeled how to blend whispers, moans, whistles, and lullabies into a coherent narrative voice. The lion on the cover, tamed yet potent, is the perfect emblem: Riperton had no interest in declawing emotion—only in showing that ferocity and tenderness might share the same golden pelt. All these years later, her paradise still beckons, not as escapism but as evidence that the deepest adventures begin inside the breath and end where a listener decides to linger.

Great (★★★★☆)