Milestones: All Eyez On Me by 2Pac

Death Row’s resources gave 2Pac room to go bigger than his peers. His fourth LP pairs blockbuster singles with fear, spite, and self-scrutiny. A triumph double-disc that stays keen even at its widest.

Foolish, embarrassing, megalomaniacal, excessive, overacted.

The list of adjectives that come to mind when evoking the rivalry between Tupac and Biggie, between the West Coast and the East Coast, is long and bewildering. Rich in hyperbole and contradictions. Above all, it reflects the media’s inability to conceive of Tupac as a total artist, whose mode of existence extends beyond the framework of music through his references to the Black Panthers, religion, Shakespeare, and cinema—references that most journalists never had the courage to read between the lines. Too crude, too metaphorical, or not entertaining enough to be deciphered, they are nonetheless those of an artist who seems to follow only his instinct, his mood swings, and who, behind the more or less muddled commentary about him, remains the author of an album as ambitious, excessive, hit-laden, and accomplished as All Eyez On Me.

To promote it, 2Pac gave everything of himself. He performed several concerts in Las Vegas, Cleveland, Hollywood, and New Orleans, requested that the album’s release be pushed back from its initially planned holiday season date in order to shoot seven music videos, performed two songs alongside Ice-T on the set of Saturday Night Live in April 1996, and granted countless interviews. Every time, his eyes were wide open, too excited at the prospect of presenting his new philosophy, of laying out his program with diabolical dynamism, without leaving the slightest opening for his interviewer. “Rap,” he told journalist Angie Martinez, “should be more focused on money, on crazier music too, but above all on money, because with it we could really do something for our communities, where the artists come from... Let’s start newspapers, build buildings, community centers—but you can’t have any of that without money.”

If All Eyez On Me sent the numbers into a frenzy and constituted a turning point in the field of hip-hop, it is also—beyond the promotional aspect—because it announced a program that was about to set a precedent: allowing oneself to spread one’s creativity across a double album, alternating between party tracks and introspective ones with total impunity, using novelistic techniques to tell the truth without disguising it as fiction, freeing speech from its clichés and conformism that would have made it more palatable. Hip-hop became a total experience. Within these twenty-seven varied and dazzling songs, within this constant sensory whirlwind, there was enough to shatter frameworks, borders, minds, and bodies. There were fantastic grooves, choruses that were ultimately very pop and dazzling G-funk, violence and poetry, a wild arrogance, an astonishing force and an impressive pointillism, a thoughtfulness and a ferocity that allowed it to rise well above the rest.

At a time when mainstream acceptance guaranteed rappers a regular presence atop the charts, All Eyez On Me fits within the continuity of albums released the same year—such as The Score by the Fugees, Reasonable Doubt by JAY-Z, ATLiensby Outkast, Hell On Earth by Mobb Deep, It Was Written by Nas, and The Coming by Busta Rhymes—in the sense that it managed to align all the planets of pop relevance: musical inventiveness, political abrasiveness, adolescent provocation, but also—much to the dismay of critics who always preferred to focus on Wu-Tang’s esotericism, De La Soul’s coolness, or indie rap’s intellectual posturing—to elevate the codes like no other hip-hop artist before by upending the genre’s unspoken rules, the expectations of curious listeners, and borders. Invited here were rappers from New Jersey (The Outlawz), New York (Method Man, Redman), the Bay Area (E-40, Richie Rich, Rappin’ 4-Tay, Dru Down), and Los Angeles (Dr. Dre, Kurupt, Snoop Dogg, Nate Dogg, etc.).

That speaks to the ambition of this complex and complete work, for which 2Pac monopolized the entirety of Can-Am Studios in Tarzana, California, where the Death Row team had its home base. For the first time in his career, he no longer had to worry about recording costs — Suge Knight allowed him to be free. He took the opportunity to condense his entire life and body of work, juggling contradictions and disparate registers.

Yet the tracks never lift off from the street. There is always a “niggaz” or a slang word to bring it back down to the level of a street credibility that Pac was experiencing in real time with his era. And it’s thrilling to hear, as All Eyez On Meseems to be the best that hip-hop could offer in 1996. Unlike albums so prolific that it sometimes becomes difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff or pull out one or two standout tracks, here everything captivates, impresses, and proves that 2Pac had just delivered the great album he had been carrying inside him from the start. Throughout this record, it is an MC at the peak of his powers on display.

A 2Pac who is fired up, breathless, sharp-tongued—less plaintive than on Me Against the World and more conquering than on Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z. A 2Pac who, drawing on his experience, moves seamlessly from diatribe to introspection with just the right amount of ferocity, writing talent, and metaphor to avoid the trap of sanctimonious conscious rap, and to deny ammunition to those who wanted to confine him to an activism he broadly wished to move away from here. And to top it all off, despite a production handled by multiple hands—at a time when records released in the same period were often the work of a single producer (Guru and DJ Premier, Ice Cube and the Bomb Squad, RZA and Wu-Tang)—All Eyez On Me avoids the trap of the indigestible, arid, and austere patchwork album.

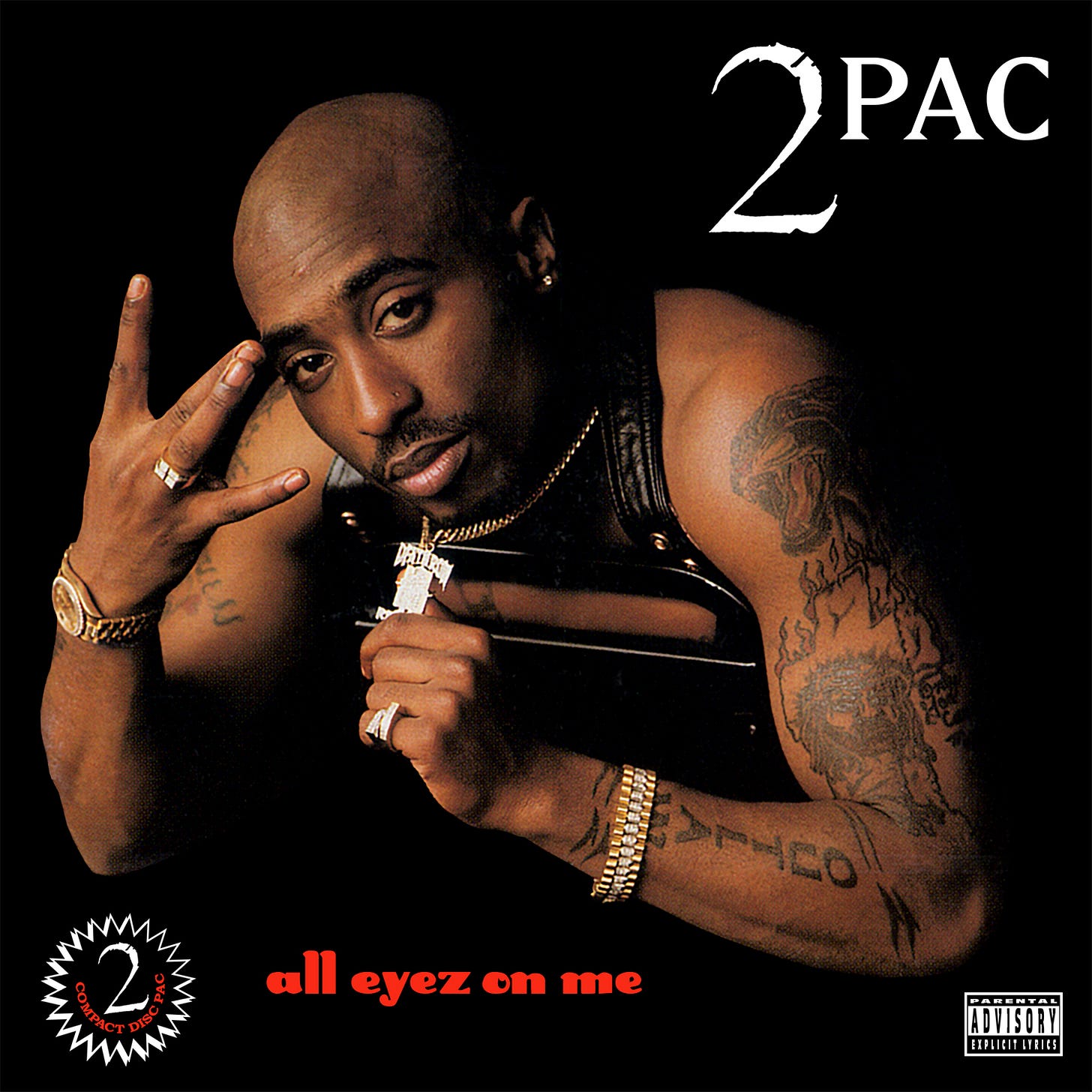

Its cover art speaks just as loudly about Tupac’s metamorphosis. Gone was the sobriety of Me Against the World; the new stallion of the Death Row stable proudly sported the label’s medallion, a Rolex watch and bracelet, flashy rings, and a black leather vest by Jean-Paul Gaultier that revealed his many tattoos. His attitude had changed as well. His easygoing demeanor had given way to a menacing posture, embodied by red eyes—likely produced by marijuana fumes—and the “W” sign thrown up with his right hand, meant to symbolize his allegiance to the West Coast.

Suffice it to say that All Eyez On Me was not merely another chapter. It opened up extraordinary new perspectives, particularly through a sonic approach that was more developed, varied, and assertive than anything before. It continued and elevated the Death Row aesthetic by collaborating with in-house producers (Dr. Dre, DJ Pooh, and Daz), but also with loyalists like DJ Quik (under the alias David Blake) and Johnny J. Since Me Against the World, 2Pac and Johnny J had been seeing each other and hatching, over long, liquor-fueled conversations, what they believed to be the future of hip-hop. The bandana-wearing man’s time in prison had changed nothing. Upon his release, he barely took the time to go eat chicken at El Pollo Loco before reconnecting with his producer.

Until then, Johnny J had mostly been working with MCs who had little inclination to understand how his melodies functioned. He had enjoyed a small success with “Knockin’ Boots” by Candyman in 1991 and worked on “Death Around the Corner” during the Me Against the World sessions, but the situation was beginning to depress him. He felt as though he was composing only for his own pleasure, frustrated that no one else was calling to collaborate with him. His stroke of luck, ultimately, was establishing himself with 2Pac at a moment when Dr. Dre was no longer the man who did everything at Death Row.

But destiny alone is sometimes not enough. It takes dialogue, respect, mutual sacrifices, and rituals. If their partnership worked so well, it was because the division of labor matched each one’s talents, but also because the writing process was always the same. Johnny J paid close attention to the sonority of the words 2Pac chose. 2Pac, for his part, did his best to be in tune with the emotions contained in his producer’s beats. “It was like we were meant to collaborate. When the lyrics landed on my compositions, I felt like I was in heaven. I’d say to myself: ‘Oh my God! What a relief!’ And it wasn’t because it was Tupac—I wasn’t on some star-struck trip. It was more like: ‘Finally, an artist who understands what I’m trying to do with my beats.’ And he looked at me like, ‘Finally a producer who knows how to showcase my lyrics.’”

All Eyez On Me was therefore their opportunity to impose their stamp, to dictate the rules of the game. By September 1996, they had recorded nearly one hundred and fifty tracks, but the title track remained their first masterpiece: “That was the very first song we made together when we linked up at Death Row. When he had just gotten out of prison, two days later he was telling me: ‘J, I want you in the studio, I’m with Death Row now.’ I thought it was a joke. I was thinking: ‘No way, 2Pac is in prison!’ He was telling me: ‘J, I’m out.’ I went over there, and after fifteen minutes of session, the first beat I had was ‘All Eyez On Me.’”

Though he had only been by his side for a few months, Johnny J had forged a bond with 2Pac that made him part of the inner circle. In the studio, he was one of the rare people who fully understood the musicality of his rhymes, his way of laying down his verses, and his refusal to deliberate for hours over the same track. Like him, he created everything in the moment, never entering the booth with scraps of paper compiling ideas born hours earlier. The eleven Johnny J instrumentals retained on All Eyez On Me, out of the eighteen originally composed, were all shaped according to the atmosphere of the moment. “Honestly, I think I was the only producer he worked with who could tell him, ‘You need to redo that take one more time, or redo that hook,’ without hearing him say, ‘Go fuck yourself and get out of my studio.’ He wouldn’t let other producers cut him off while he was rapping.”

In the documentary Tupac: Resurrection, we can indeed see Tupac during the All Eyez On Me sessions. The words are direct, the rhythm intense, and there is no question for him of reining in his energy. One might think he feared being shot again, or simply that he dreaded going back to prison if his appeal was rejected. In any case, he didn’t “think he’d be around much longer,” so he might as well keep going. “You’ll mix later,” he told one of his producers. “Bring the guys in to add the drums when the rappers are gone. Keep that rhythm, add the guys, mix everything. Everyone’s going to say: ‘That’s the hook.’ You’ve got the hook and the song.”

In another video, he appears even more determined. “We only have two weeks to make this album. To mix it and everything,” he argues in a machine-gun delivery. “We can’t afford to linger on a single track.”

“We need to find a way to speed all this up. Me, I made my whole album by knocking out three tracks a day. I’d write, I’d record... You can mix later, but no, you guys like spending all night at the studio, adding a beat here and there. You can do that after. You like hanging around the studio, finding that killer sound. But meanwhile, there are eight rappers sitting around doing nothing. Damn, get to work! For the track title, who cares, we put whatever we want. We record it, we’re done, we’re out. You like the hook? We keep going. You don’t like it? We start over. We add a scratch and it’s in the can.” An unglamorous mode of production, worthy of Fordism, but one that allowed him to accelerate the creative process.

It’s that simple: between his release from prison and his death in September 1996—a span of barely eleven months—Tupac recorded nearly two hundred tracks, including twenty-four across three different studios during his first two weeks of freedom. When he agreed to leave the studios, it was almost exclusively to shoot a music video, act alongside Tim Roth in Gridlock’d, enjoy some good times eating his favorite dishes—mainly curry shrimp or chicken wings—, clear his mind by cruising down Sunset Boulevard or playing a few rounds of paintball, and make a brief appearance at a party. Big Syke explains: “I was living with him at his Peninsula villa in Beverly Hills, and for three or four months, we’d get up in the morning. We’d get up early every day and, around noon, we’d head to the studio. We’d usually leave the studio around ten at night and hit the clubs, every day.”

In between, he churned out tracks one after another, drowned his mind in the haze of a blunt, and swapped his limousine for a van fitted with a sleeping berth to steal a few hours of sleep from life before going back to work. He also demanded total availability from his collaborators, a commitment that sometimes pushed the limits of what was bearable. Dave Aron, one of the sound engineers, can attest to this. Hired to work on various tracks, including the opening “Ambitionz Az a Ridah,” he recalls: “That’s the first song I did with Tupac. The day he got out of prison, he didn’t go to a club. He didn’t try to meet women. He went straight to the studio like it was a mission, and he recorded ‘Ambitionz Az A Ridah.’” Placed as the album opener and driven by an enormous bassline, those four minutes and forty seconds are enough to confirm the trajectory: without ever taking the easy route, 2Pac heightens his thug mentality here and impresses as much with his overflow of testosterone as with his dazzling hook: “I won’t deny it, I’m a straight ridah/You don’t wanna fuck with me/My ambitionz az a ridah/Got the police bussin’ at me/But they can’t do nothin’ to a G.”

The truth is that All Eyez On Me, initially titled Supreme Euphanasia or simply Euphanasia, is in a way the story of a rapper who sees writing as an elite sport, with a Holy Grail to reach and opponents to defeat. “2Pac was very committed to the idea that the album had to be spontaneous,” explains one of the sound engineers, Rick Clifford. “Everything you hear on the album was done in one take. You couldn’t go back and change something. If a guy can’t just step up and deliver eight to sixteen bars on the spot, he’s not ready yet. He’d say he loved the first take because it always carried a particular emotion. He said that if you went back and tried to change something, you’d start overthinking what you did and you’d start losing the emotion that came with the take, that you’d end up ruining it. The only one who pushed back on this policy was Snoop. He said he’d come back the next day and do his part. I believe Snoop went home, wrote his verse, memorized it, and came to the studio to nail it on the first take.

Snoop told 2Pac, ‘Hold on, you’re not gonna cut me from this thing over a botched first take. I’ll come back and do my thing tomorrow.’” Perhaps it’s because 2Pac always said he joined Death Row to be around Snoop Dogg, whom he admired and found cool. Perhaps it’s simply because the author of Doggystyle was already too influential in the rap game for anyone to impose certain restrictions on him. Either way, 2Pac could be satisfied that he gave his new associate a little more time. The other tracks recorded alongside Snoop weren’t retained, but with “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted,” he had one of the most resounding singles on All Eyez On Me, if not in his entire discography. Rarely, in fact, has a title been so explicit. “The Two Most Wanted Americans” refers to the recent events that had crossed the lives of 2Pac and Snoop Dogg, who was then accused of being an accomplice to murder. And the revenge of the two partners promised to be devastating.

“Snoop and I are the core of the ghetto. Snoop is the calm rapper, steady, who follows the rules. He handles his business without making waves. I represent the rough side, the hard side, the ‘anything goes’ side. We represent both sides of the mirror. The calm and the relentless.” Here, nothing pandering, no flirtation with the R&B formula that dominated among part of the competition at the time, but an insolent, flashy gangster attitude that they develop in the music video. Loosely adapted from a scene in Scarface where Tony Montana addresses his detractors before gunning them down, the video opens with 2Pac, his arm bandaged, flanked by his two henchmen, facing off against two lookalikes of Puff Daddy (Buff) and Biggie (Piggie), whom they accuse of being behind the Quad Recording Studios shooting. The two Bad Boy Records rappers are terrified (“Pac, you’re alive? I mean, are you okay?”), they fear for their lives, but Pac, magnanimous, simply issues a warning (”I’m not gonna kill you, Pig. Once we’re boys, we stay boys”), pulls a cigarette from his pocket, and walks away, lordly: “Don’t thank me.”

There is, however, a censored version of “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted,” directed by Gobi after 2Pac fired the first director for not following his instructions. In this version, more violent and provocative, 2Pac is less charitable and lets his bodyguards finish the dirty work. The scene is shocking, but it fits the song’s message, its vengeful tone (”They wonder how I survived five shots / But niggas are hard to kill where I’m from”) and its ambition to change the sound of hip-hop forever. “This is going to become the anthem of rap on the West Coast. It’s going to revolutionize the music scene.” 2Pac puffs out his chest, no longer doubts anything. But behind the freedom of such an approach, there’s the flip side, and for once, the violence of the video, the outrage it provokes among the self-righteous, masks the true nature of the track, as vindictive and outrageous as it is referential.

Because behind the megalomaniac poses, the vulgarity of the lyrics, and the borrowings from Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message” (”Sho nuff, I keep my hand on my gun, cuz they got me on the run”) and MC Fosty & Lovin’ C’s “Radio Activity Rapp (Let’s Jam),” 2Pac manages to craft a mythic track here, renamed “gangsta party” by fans, whose aggressive approach is continued on other tracks that also bring the G-funk style to its quintessence: “Can’t C Me” and “Got My Mind Made Up,” recorded at Kurupt’s place alongside—and here lies its distinction in the midst of the East Coast/West Coast war—Method Man, Redman, and an Inspectah Deck ultimately left off the final version.

All Eyez On Me is also a party record. Two tracks attest to this. The first was released as a lead single in late December 1995. It was 2Pac’s first single for Death Row, and also the first to be released since his release from prison. And what a track! “California Love” is a bomb, crafted alongside Dr. Dre and Roger Troutman over a Joe Cocker sample (”Woman to Woman”). “I came in and told Dre, ‘I need a track.’ He was working on ‘California Love.’ I told him, ‘You owe me this one. I just got to Death Row, I’m fresh out of jail. You’re nowhere near finishing your album, so...’”

Under pressure from Suge Knight, Dr. Dre complied. It stuck in his throat a little, but he respected Tupac. He knew it was rare enough to collaborate with MCs “as talented as him,” capable of finding “the words while singing.” And besides, he had a hit on his hands. Radio stations played it on a loop. DJs made it their secret weapon for getting b-boys and thrill-seeking kids alike on the dance floor. And MTV unveiled footage from a video that, based on an idea from Jada Pinkett-Smith, borrowed from the third installment of Mad Max, Beyond Thunderdome. Directed by Hype Williams and shot at El Mirage Dry Lake Bed, with appearances by actors Chris Tucker and Tony Cox, the “California Love” music video, budgeted at approximately $600,000, was a war machine.

Added to this was the video for “How Do U Want It,” directed by Ron Hightower and first aired on September 14, 1996, on Playboy Channel’s Hot Rocks: Back to School. The rap world was still deep in mourning, but the video still managed to cause a sensation. By all accounts, journalists, rappers, and producers were unanimous: they had never seen such a video before. Shot alongside porn actresses Heather Hunter and Nina Hartley, the uncensored version piles up suggestive poses, bare breasts and buttocks, orgy scenes, and masturbation. An atmosphere reminiscent of the orgies that sometimes took place in the studio, but also of an overtly sexual and machismo-driven track where the woman comes to satisfy the man’s sexual needs, preferably in the hot tub of an enormous villa, before going off to scrub the floor or do the dishes. Here, verbally degrading women becomes a stylistic exercise that produces some striking verses—like the one 2Pac chose to open “How Do U Want It” with:

“Love the way you activate your hips and push your ass out

Got a nigga wantin’ it so bad I’m ‘bout to pass out

Wanna dig you and I can’t even lie about it

Baby, just alleviate your clothes, time to fly up out it

Catch you at a club, oh, shit you got me fiendin’

Body talkin’ shit to me but I can’t comprehend the meaning

Now if you wanna roll with me, then here’s your chance.”

From start to finish, it’s nothing but oral sex and penetration, green bills in girls’ G-strings and champagne flowing over their chests, gang bangs and screwing as many women as possible before a potential demise. The theme seems easy, the lyrics don’t exactly drip with poetry, but that doesn’t stop 2Pac and Johnny J from ranking this track among their favorites on All Eyez On Me. For the latter, it’s understandable. He’d been sitting on the beat for four years, weathering rejections from various rappers. When 2Pac hears it, he claims it instantly. “When I played it for Tupac, he told me, ‘It’s going to be called “How Do U Want It,”’” Johnny J recalls, his voice tender, slightly fogged by nostalgia.

“Then he wrote his verses, and he came in with this melody and these words, and he started singing ‘How do you want it? How does it feel? Coming up as a nigga in the cash game, living in the fast lane.’ So he went into the booth and started singing the hook himself, with no vocalist handling the backing. That was before we thought of bringing in K-Ci & JoJo. And honestly, I loved the fact that the original version featured Tupac singing. He sang the hook, and the entire lyrics and melody were written by him. He probably couldn’t sing perfectly on time, but I knew exactly which notes he was reaching for. He had this gift of knowing where the melody needed to go. He was more than just a rapper.”

The duo then invited some girls to lay their vocals on the hook, but nothing worked. They didn’t have the required level; their tone didn’t match the desired feel. The problem was that 2Pac was reluctant to have a female presence on this track. He considered calling on Danny Boy again, but K-Ci & JoJo, two members of the quartet Jodeci, seemed to have been in his good graces for a few months. He was convinced—only they could get the job done. It was up to Suge Knight to be persuasive. That, he usually knew how to do. So the negotiations didn’t last long. “How Do U Want It” became a hit, and Suge Knight pressured various DJs in Las Vegas and Los Angeles to play it at parties.

Equally focused on the sexual act—preferably with multiple partners—”What’z Ya Phone #” has its own merits. And this time, it’s Danny Boy handling the hook, full of energy, with vocals close to R&B. Less overtly danceable than “How Do U Want It,” this homage to “777-9311” by Prince’s protégés The Time was seemingly recorded under similar circumstances. “There were always, just like in every studio, girls coming through,” the Chicago singer details. “And you’re a guy, you’re married, you’ve got your life. And then you’ve got all the stuff the record industry gives you access to. You can have all that as many times as you want, if you know what I mean.” Ensuring the presence of easy women on the premises—that’s how Death Row operated. It was the label’s guarantee that everyone could get laid, have a good time, even if it meant taking turns.

They weren’t all prostitutes, but they were known for drinking heavily, sleeping with celebrities, and loosening up the atmosphere. This vibe is precisely what fuels the content of “What’z Ya Phone #,” which opens with a phone conversation improvised at the last minute with a woman passing through the studio. “The phone call story was based on real events,” Danny Boy continues. “2Pac was constantly getting phone calls like that, girls calling him to hook up. All we did was laugh about it in the studio. We just turned it into a song by riffing on it into the mic... And actually, the woman talking on the track wasn’t credited. She probably didn’t want her mother to know it was her talking like that... She was just one of those girls who’d come through the studio...”

Apart from the headliners (Snoop Dogg, Method Man, Redman, Dr. Dre, George Clinton) and a few names that appear consistently across his various productions—Nate Dogg, Outlawz, Big Syke, Dramacydal—the true contours of the roster at work on All Eyez On Me are difficult to define. On one hand, there are the phantom members, those whose names come up regularly without anyone ever knowing the extent of their involvement. Then there are the shadow members, those who contributed without necessarily being credited. DJ Quik is a case in point. Accustomed to supporting roles since the early nineties—a period during which he invented a seventies-flavored G-funk before Dr. Dre popularized it for the world—the Los Angeles producer, despite being very active during the All Eyez On Me sessions, is only credited on “Heartz of Men,” a track that adds some sonic oddities to the album’s often well-crafted instrumentals.

“Business with Death Row was so messed up sometimes, and if you don’t go to the boss’s office with Roy Tesfay to write up the credits yourself, you get screwed. I got screwed. I did a lot of remixing on that album, trying to make everything sound its best, then mixing, and I didn’t get credited for it. I made a bunch of songs on that album sound better than they did after they were first recorded, which represents a lot of studio time. By the end, I’d remixed something like twelve tracks. But most of them didn’t end up on the album. In fact, ‘Heartz of Men’ is the only track that stayed on the final version of the album. [...] My job as a producer is to handle the musical side so he has a beat he feels comfortable enough on to lay down everything on his mind. And I think that’s what we managed to do—a beat that charges forward, that’s ferocious, so he could lay his rapid, wild flow over it. 2Pac was a seasoned artist. He really thought about what he was going to write, to the point of almost becoming part of the song itself. Almost as if he wanted his words to be imprinted on it forever. He was so meticulous when it came to how he wrote the lyrics to his songs. It was the same for me regarding this track. As legendary as 2Pac was, I had to remember that my job as a producer was to make the track as close to perfection as possible.”

What imprints itself in the memory of DJ Quik, Johnny J, and the other producers like Daz Dillinger—who originated “Ambitionz Az A Ridah,” “Skandalouz,” “2 Of Amerikaz Most Wanted,” “I Ain’t Mad At Cha,” and “Got My Mind Made Up,” originally composed for Tha Dogg Pound’s album Dogg Food—is also this ability to hold up a terrifying mirror to Bill Clinton-era America. Because what several tracks deal with is indeed urban poverty: squalid housing, broken families, open-air drug deals, the despair and violence of the gangsters he pretended to run with at the time. Of course, there’s the crew, the hearty back-slaps, the female conquests, and the party tracks, but 2Pac always considered himself an activist. He remained that artist engaged with society, the one who didn’t hesitate to use his position to raise his voice or to express himself in an intimate register, without affectation. He may not have spent long hours meditating over his lyrics, nourishing them with dreams and readings of Romantic poets, but he was always capable of going beyond his singles and misogynistic tracks to showcase a breathtaking narrative instinct, one that could extract the best from a medium according to a narrative logic.

Johnny J recounts: “When he joined Death Row, he had to adopt this aggressive approach because that’s what fit the label, but I loved Pac for his ability to keep an emotional side in his tracks. And that was something the label respected, without a doubt.” More than respect, it was a passion that Death Row’s executives harbored for the more thoughtful tracks from their star. Placed ninth on the first disc’s tracklist, “Life Goes On” was Suge Knight’s favorite song—the one he listened to every morning, the one that helped him understand his protégé’s doubts. 2Pac had reached a stage where he could see the shortcomings and even the contradictions in what he was doing, but he remained convinced that society forces people to do things that go against their souls. Through an ingenious narrative process, without excessive theatrics but with, always, a great deal of emotion, “Life Goes On” confirms the sensitivity and fragility of its author. It’s no longer just the confessions of the depressed, as on Me Against the World, but a brilliant chronicle of his anxieties and grudges. Listening to the third verse, the most famous of all, what he offers the listener is something like a funeral oration:

“Bury me smilin’ with G’s in my pocket

Have a party at my funeral, let every rapper rock it

Let the hoes that I used to know

From way befo’ kiss me from my head to my toe

Give me a paper and a pen, so I can write about my life of sin

A couple bottles of gin, in case I don’t get in

Tell all my people I’m a Ridah

Nobody cries when we die, we Outlawz, let me ride

Until I get free

I live my life in the fast lane, got police chasin’ me

To my niggaz from old blocks, from old crews

Niggaz that guided me through back in the old school

Pour out some liquor, have a toast for the homies

See, we both gotta die, but you chose to go before me

And brothers miss you while you gone

You left your nigga on his own; how long we mourn? Life goes on.”

Depression and redemption—2Pac now dispensed them like a demiurge. This was evident in the studio, but also outside of it. He wore a bulletproof vest day and night, carried one or two guns in his pocket, and never stayed in the same place for long. American photographer Mike Miller, whose shots of Warren G, Cypress Hill, and Snoop Dogg are worth their weight in gold in hip-hop history, still remembers the various photo shoots done alongside him. They were always studious, sometimes lasting a good ten hours, but often interrupted for various reasons.

“He was really easy to get along with and work with. He wasn’t at all schizophrenic like some people claimed. He could lose his temper from time to time, but like any guy who’s barely in his twenties. Few people know this, but he’d sometimes give money to people who came to thank him for his music. Why? Because he loved people and wanted to help. On the other hand, if you didn’t like him, then he didn’t like you. Nothing more normal. The only downside, really, was the craziness of his fans. Every time, it took us forever to find a spot quiet enough in Los Angeles where we could work in peace. Their passion was insane. I can’t even tell you how many times we had to change locations because of their enthusiasm, or because gangs nearby would rush toward us when they found out where he was.”

In such a climate of fear, the melancholic tracks could have piled up like variations on a single theme.

Each of these tracks possesses, on the contrary, a complexity of its own, and one can only bow before the choice of beats, varied and unique. Routine was never 2Pac’s thing. While some listeners may not notice the difference, he had other ambitions. He wanted to make history and seemed open to any idea that could help him accomplish this honorable mission—even if it meant removing a track or two to integrate others at the last minute. Like “Heaven Ain’t Hard 2 Find,” placed as the final track on the second disc. Quincy Jones III recalls here on production:

“When I heard ‘Dear Mama,’ I understood that he was one of the first rappers to have made a song whose emotion truly moved me. At that point, I started listening to his music, and after he got out of prison, I contacted him to ask if the album was already finished. He told me it was and that he wanted to hear what I had done. I gave him a cassette with ‘Heaven Ain’t Hard 2 Find’ and he told me it was exactly what he needed right now. He removed a track from All Eyez On Me and added ‘Heaven Ain’t Hard 2 Find.’ And he recorded so quickly, and he was so cool and real throughout the entire night, that I took our collaboration as a gift. I had never witnessed such a spectacle since my beginnings as a rap producer.”

That track isn’t the only one to reveal its author. From start to finish, All Eyez On Me contains entire swaths of his childhood (Machiavelli was my tutor, Donald Goines, my father figure/Mama sent me to go play with the drug dealers,” on “Tradin War Stories”), attacks directed at unscrupulous women (“Skandalouz”), fears (“The federales wanna see me dead, niggas put prices on my head/Now I got two Rottweilers by my bed, I feed ‘em lead/Now I’m released, how will I live?/Will God forgive me for all the dirt a nigga did, to feed kids?/One life to live, it’s so hard to be positive/When niggas shootin’ at your crib,” on “Picture Me Rollin’”), and offers anyone willing to listen his reflections and doubts—but always with perspective and lucidity. As an example, “I Ain’t Mad At Cha,” whose piano loop is based on a sample from a DeBarge track (”A Dream”)—those young Motown protégés of the eighties—approaches with melancholy the passage of time and evokes with striking lucidity how people’s behavior toward him changed once he became famous.

Written alongside “Ambitionz Az a Ridah” the evening of his release from prison, “I Ain’t Mad at Cha” is interesting because, on the one hand, it sets aside Tupac’s anger—he declares here repeatedly that he has nothing but love to give and bears no grudge against his adversaries—and on the other hand, it gives life to a music video that, beyond its kitsch and dated aesthetic, speaks volumes about his state of mind in August 1996. Here, we see him die in the very first seconds of the video after saving his friend’s life—the actor Bokeem Woodbine, whose casting was insisted upon by Tupac. It’s a bitter scene, sadly prophetic, but the rapper ultimately ascends to Paradise and now spends his time among the great figures of Black music: Jimi Hendrix, Miles Davis and Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Redd Foxx, and others.

These references to the afterlife—which would delight hundreds of amateur theorists after his death—are found at the heart of “Only God Can Judge Me.” More than a simple track, this is a manifesto delivered by 2Pac, a song to be understood as a slogan that dozens of rappers have not hesitated to borrow—Booba’s “Only God will judge me” on “Tallac” being one example among many. Here, 2Pac and his gift for phrasing work wonders: “Only God Can Judge Me” is a half-heroic, half-sorrowful tale, sustained by veiled rhymes, devoid of certainty, packed with nuances, fears, and spiritual questioning:

“Perhaps I was blind to the facts, stabbed in the back

I couldn’t trust my own homies, just a bunch of dirty rats

Will I succeed? Paranoid from the weed

And hocus pocus, try to focus, but I can’t see

And in my mind, I’m a blind man doin’ time

Look to my future, ‘cause my past is all behind me

Is it a crime to fight for what is mine?

Everybody’s dyin’, tell me what’s the use in tryin’

I’ve been trapped since birth, cautious, ‘cause I’m cursed

And fantasies of my family in a hearse

And they say it’s the White man I should fear

But it’s my own kind doin’ all the killin’ here

I can’t lie, ain’t no love for the other side

Jealousy inside, make ‘em wish I died

Oh my Lord, tell me what I’m livin’ for

Everybody’s droppin’, got me knockin’ on Heaven’s door

And all my memories of seein’ brothers bleed

And everybody grieves, but still nobody sees

Recollect your thoughts, don’t get caught up in the mix

‘Cause the media is full of dirty tricks.”

By the time the first verse ends, 2Pac has already said a great deal. With a seemingly simple tongue, he has just highlighted the fatality of a bleak destiny, while offering the curious listener the possibility of perceiving a second or even a third layer of meaning. His second verse—the third being handled by Rappin’ 4-Tay—goes even further in this process of introspection. Opening with the beeps of his heart monitor, it reveals a certain form of despair:

“I hear the doctor standin’ over me, screamin’ I can make it

Got a body full of bullet holes, layin’ here naked

Still, I can’t breathe, something’s evil in my IV

‘Cause everytime I breathe I think they killin’ me

I’m havin’ nightmares, homicidal fantasies

I wake up stranglin’, danglin’ my bed sheets

I call the nurse ‘cause it hurts to reminisce

How did it come to this? I wish they didn’t miss

Somebody help me, tell me where to go from here

‘Cause even thugs cry, but do the Lord care?

Try to remember but it hurts

I’m walkin’ through the cemetery, talkin’ to the dirt

I’d rather die like a man than live like a coward.”

Whatever album 2Pac wrote, the lyrics he put forward very often bear witness to psychological distress. He acknowledged it. Filling miles of blank pages and offering them to the listener cost him far less than paying a therapist to understand his paradoxes and resolve the duality between morality and gangsta codes. If it could also enrich him and free him from a few lingering scars, then all the better—every little bit helped. “During the recording of his spiritual or sad songs, he never cried in front of me, but I could see a change in his demeanor. In his body language, you could see that something was affecting him emotionally.” Listening to “Life Goes On” and “Better Days,” Johnny J confirms, “hardcore dudes, straight from the streets, would walk out of the studio crying. Suge loved those too—I didn’t see him cry, but I could tell he was definitely moved by those songs...” Dru Down was also present during the recording of “Life Goes On.” He adds: “When Pac and Johnny J got serious, there wasn’t really anyone left in the studio. When those niggas tried to be serious, Pac would sweep the weed off the mixing board and start writing. And the niggas who stayed had to be quiet.”

But ultimately, the methods employed didn’t matter; it didn’t matter that he sometimes gave the impression of not always rapping on beat; it didn’t matter that Fatal Hussein and Yafeu Fula were thrown out while recording “All About U” on the grounds that they were too drunk and high to produce anything of value. 2Pac had just given life to an album that was about to shatter every record in the music industry. By all accounts, by debuting at number one in sales in 1996 and being certified platinum in barely a week, he became much more than a successful rapper: a phenomenon of global magnitude.

He was no longer fighting against the world—he was dominating it. Records were selling by the millions, his face adorned T-shirts honoring his greatness, and he inspired a new generation to enter the battle in turn. The press could only follow the movement, and Rolling Stone was highly complimentary in its review, going so far as to see in All Eyez On Me the gangsta version of Pink Floyd’s The Wall, while L.A. Weekly compared it to the famous double album by four lads from Liverpool: “If the Beatles’ White Album broke the rules by containing an entire genre in each song, All Eyez On Mecontinued the approach by exploring the full range of human emotions.”

Through its musical ambition, with its staggeringly lush productions—light-years from the haunting minimalism that Jerry Duplessis was cooking up for the Fugees at the same time—through the diversity of its themes, through its universal recognition, through its duration (one hundred and thirty-two minutes), through its refusal to be locked into any street stereotype, All Eyez On Me transcends the codes of gangsta rap. Tupac does fall here and there—whether in certain music videos or a few lyrics—into a street variation of Hollywood gangster films, but, fierce, mocking, engaged, and incisive, he had above all just composed one of the very rare records in the history of popular music to have never suffered under the weight of the years, nor lost any of its splendor in the face of shifting times. Gifted with an ambitious, eclectic vision, as well as formidable virtuosity and volubility, All Eyez On Me also represents the finest taste in Black music in 1996—much as N.W.A., Marvin Gaye, or Miles Davis had five, twenty, and thirty years before.

Standout (★★★★½)