Milestones: Anti by Rihanna

After seven albums in seven years, Rihanna stopped the machine. Anti is what happened when she finally made a record for herself.

One thing about Rihanna, she has never been precious about her own image. This is not an obvious observation. Most pop stars at her level—and by 2016 there were maybe three—protect themselves with mystique or reinvention cycles or very expensive handlers. Rihanna did none of that. She released records annually like a factory, accepted songwriting from whoever had the strongest hook, let Calvin Harris or Stargate or Sia shape the sound while she delivered the vocal with just enough grain to mark it as hers. She was available in a way that made her seem inexhaustible. And then she went quiet.

The gap between Unapologetic and Anti—four years, an eternity in her career—became its own kind of event. Kanye West signed on to executive produce, then walked. Singles dropped and vanished with “FourFiveSeconds,” which had Paul McCartney strumming acoustic guitar like a busker, and “Bitch Better Have My Money” arrived wrapped in blood-spattered theatrics. Neither made the final tracklist. She told MTV News in March 2015 that she wanted something she could still perform in fifteen years, something that wouldn’t feel burnt out. That phrasing is exact: burnt out. She had been singing songs she no longer believed onstage, watching her own catalog age past her. Anti had to fix that.

The album opens with SZA. This is significant. “Consideration” was not written for Rihanna—SZA had recorded it for Ctrl, had shot a video, was days from release when Rihanna’s team negotiated it away. The transfer was handled above SZA’s head. She told Variety years later that she felt frustrated, that she had convinced herself she would never make anything that good again. But Rihanna heard the song and wanted it badly enough to build her entire project around it. The production stutters and distorts, a bassline thudding underneath patois phrasing and SZA’s wisp of a vocal on the refrain. Rihanna asks for consideration, for peace of mind, for the room to do things her own way. She told Vogue it was “like a PSA.” It is. She is announcing, with someone else’s song, that she is no longer available on demand.

That announcement would mean nothing if the rest of the record didn’t hold. Anti holds. But it holds strangely—it is not the kind of album that announces itself with obvious hits or clean through-lines. The pacing is moody and illogical, moving from woozy dub to whiskey-soaked balladry to rock guitars to dancehall to psychedelia. The tempos drag. The vocals often sit low in the mix or blur at the edges. It is not a record you put on at a party. It is a record you put on at 2 a.m. when the party has ended and you’re still awake, scrolling through your phone, wondering who to call.

“Kiss It Better” is the closest the album gets to classic pop songwriting. Jeff Bhasker produced it with Glass John, and the sessions included Nuno Bettencourt, the Extreme guitarist, laying down a riff at Westlake Studios that Rihanna reportedly improvised her hook over in the moment: kiss it, kiss it better, baby. The song sounds like nothing else she had done—Prince-adjacent, drenched in reverb, her voice sliding into falsetto as she pleads for reconciliation. The lyric is straightforward, even banal: an ex she cannot quit, a request that borders on demand. But the vocal performance resists the expected climax. She does not belt. She aches. She curls around the syllables instead of punching through them. The restraint is the whole argument. Rihanna had belted enough for a career. Now she wanted to see what happened when she held something back.

“Work” became the commercial anchor, but its success almost obscured its strangeness. Boi-1da built the beat at Drake’s house in Los Angeles; PARTYNEXTDOOR wrote the lyrics. Rihanna sings in Jamaican patois, the words slurring together in a way that confused American radio at first. She told Vogue it was the most authentic thing on the record, the way people actually speak in the Caribbean: “You can understand everything someone means without even finishing the words.” The repetition—work work work work work—turns hypnotic, the vowels melting into each other until you stop hearing English and start hearing rhythm. Drake shows up for his verse, low and unbothered, trading flirtation with Rihanna in a way that by 2016 had become its own public theater. But his presence is incidental. The song belongs to her voice, her accent, her refusal to translate.

The album’s second half is where the risk becomes visible. “Yeah, I Said It” is two minutes of whispered provocation over Timbaland’s production—barely a song, more like a voicemail you delete before someone else hears it. “Same Ol’ Mistakes” is a Tame Impala cover, faithful almost to the point of karaoke. Kevin Parker’s original ran nearly seven minutes. Rihanna’s version runs the same length, keeps the same instrumental, changes almost nothing but the pronoun in her mouth. This was controversial at the time. Why cover a song you don’t intend to reinterpret? But the choice makes sense within the album’s logic. Anti is about Rihanna testing her own boundaries, seeing how far she can stretch without breaking. Singing someone else’s song wholesale, without embellishment, is its own kind of vulnerability. She is not showing off. She is seeing if the clothes fit.

“Love on the Brain” was the sleeper. It hit radio months after the album dropped and climbed slowly, reaching the top five the following year. The production nods to doo-wop, to Etta James, to Phil Spector’s wall of sound. Rihanna sings in full-throated desperation about the kind of love that leaves bruises—“It beats me black and blue, but it fucks me so good.” The vocal is ragged in places, pushing into her upper register until it cracks. She is not playing a character. Or rather, she is playing a version of herself that she had previously kept offstage: the woman who stays, who forgives, who knows the relationship is bad and calls back anyway.

“Higher” is the proof of that. At just two minutes, it is the album’s most exposed moment. The story behind it is well documented: Rihanna recorded it at five in the morning, drunk on whiskey, at Westlake Studios with vocal producer Kuk Harrell and engineer Marcos Tovar. She posted about it on Instagram at the time—“5 am drunk off da whiskey with these two rockstars”—and later compared the song to a drunk voicemail. “You know he’s wrong,” she told Vogue, “and then you get drunk and you’re like, ‘I could forgive him. I could call him. I could make up with him.’ Just, desperate.” The vocal is shredded. She strains, misses notes, slurs. It sounds like someone who has stopped caring about how she sounds. Some journalists at the time called it the album’s weakest moment. They were wrong. “Higher” is the key. It explains what Rihanna was after: not polish, not perfection, but the feeling of being caught in the act of feeling.

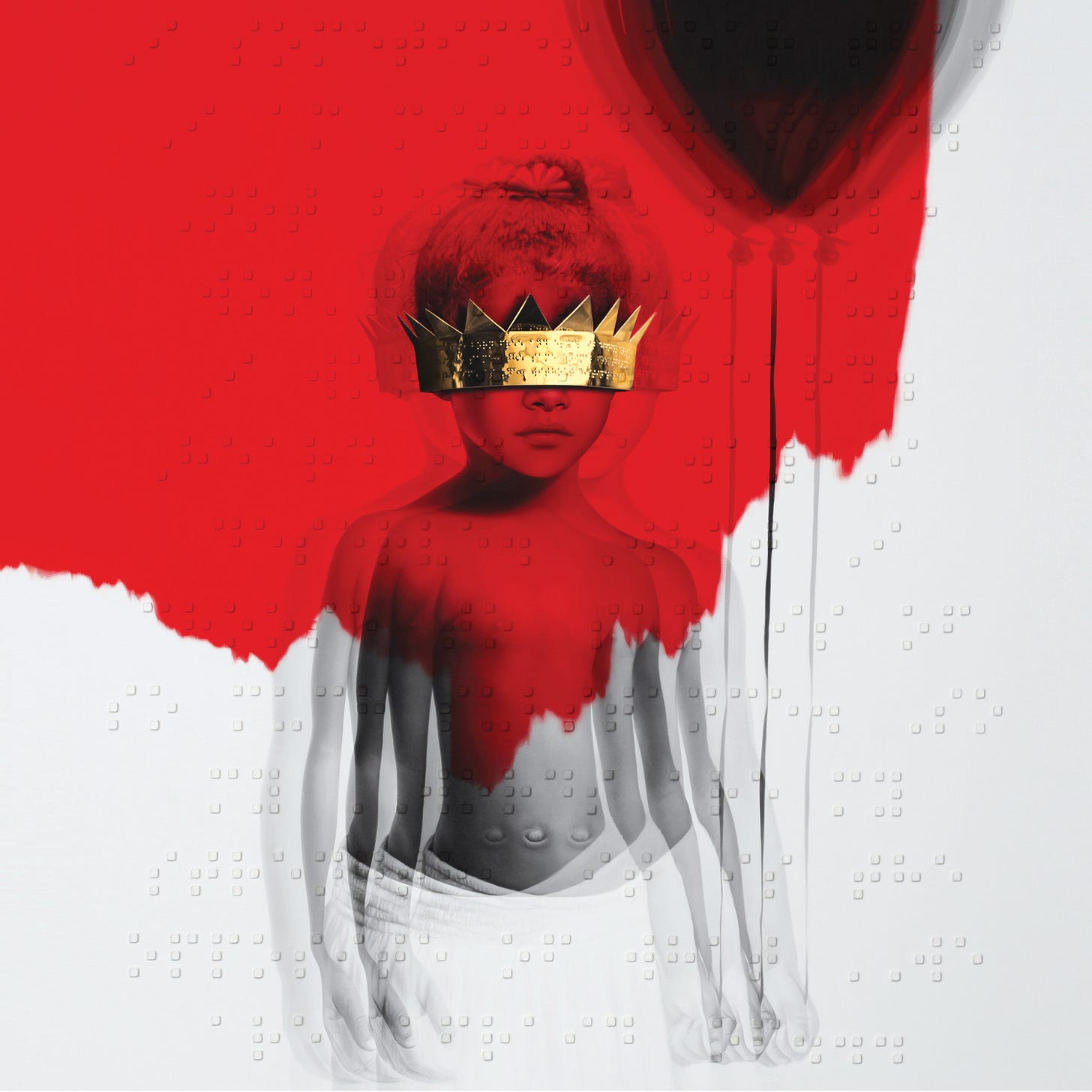

The record’s cover art came from a collaboration with Israeli-born artist Roy Nachum. He blindfolded Rihanna in his studio while her own music played and had her touch canvases embedded with Braille poetry, leaving fingerprints in charcoal. The finished image shows a young Rihanna—or a painting of her—holding a black balloon, a crown covering her eyes. It was the first major album to be released entirely in Braille. Rihanna saw the art at JAY-Z’s house, where he collected Nachum’s work, and immediately knew it was what she wanted. The concept is heavy-handed, maybe, but it connects to the album’s preoccupation with perception, with being looked at, with the exhaustion of visibility. Anti is an album about what happens when you stop performing for the gaze.

This is where the title earns itself. Anti is not a rejection of pop. Rihanna was too fluent in the form to simply walk away. It is a record made by someone who understood exactly what was expected of her and chose, song by song, to deny it. She did not want the hits that would burn out. She did not want the Auto-Tuned polish that had defined her earlier work. She wanted to sound like a person, tired and drunk and angry and still reaching toward something.

The gamble paid off, though not immediately. Initial reviews were divided—some heard a muddled experiment, others a breakthrough. But the record never left. It charted for years, became the longest-running album by a Black woman in Billboard 200 history. Lorde wrote “Liability” after hearing “Higher” and being moved to tears. Even the most disgusting human garbage Marilyn Manson cited Anti as an influence on his band’s Heaven Upside Down, pointing specifically to “Love on the Brain” as a song that hit him because Rihanna “just meant it.” The album accumulated meaning slowly, the way her earlier work never had to. Those records were designed for immediate consumption. Anti was designed to last.

Rihanna has not released another album since. She said in a 2019 interview with Sarah Paulson that during the making of Anti, she had felt numb, disconnected, as though she had disappointed God so badly that they were no longer close. The record carries that feeling. It is not a joyful album. It is not a party album. It is an album about surviving—surviving fame, surviving bad love, surviving your own image—and still finding something to sing about at five in the morning when the whiskey has worn off and the studio is quiet and you are the only person who knows whether the take was good enough.

She knew. It was.

Great (★★★★☆)

I’ve always thought Anti was her most focused album. For a long time Rihanna always felt like a singles artist. Anti was really the first time I adored a body of her work from front to back.