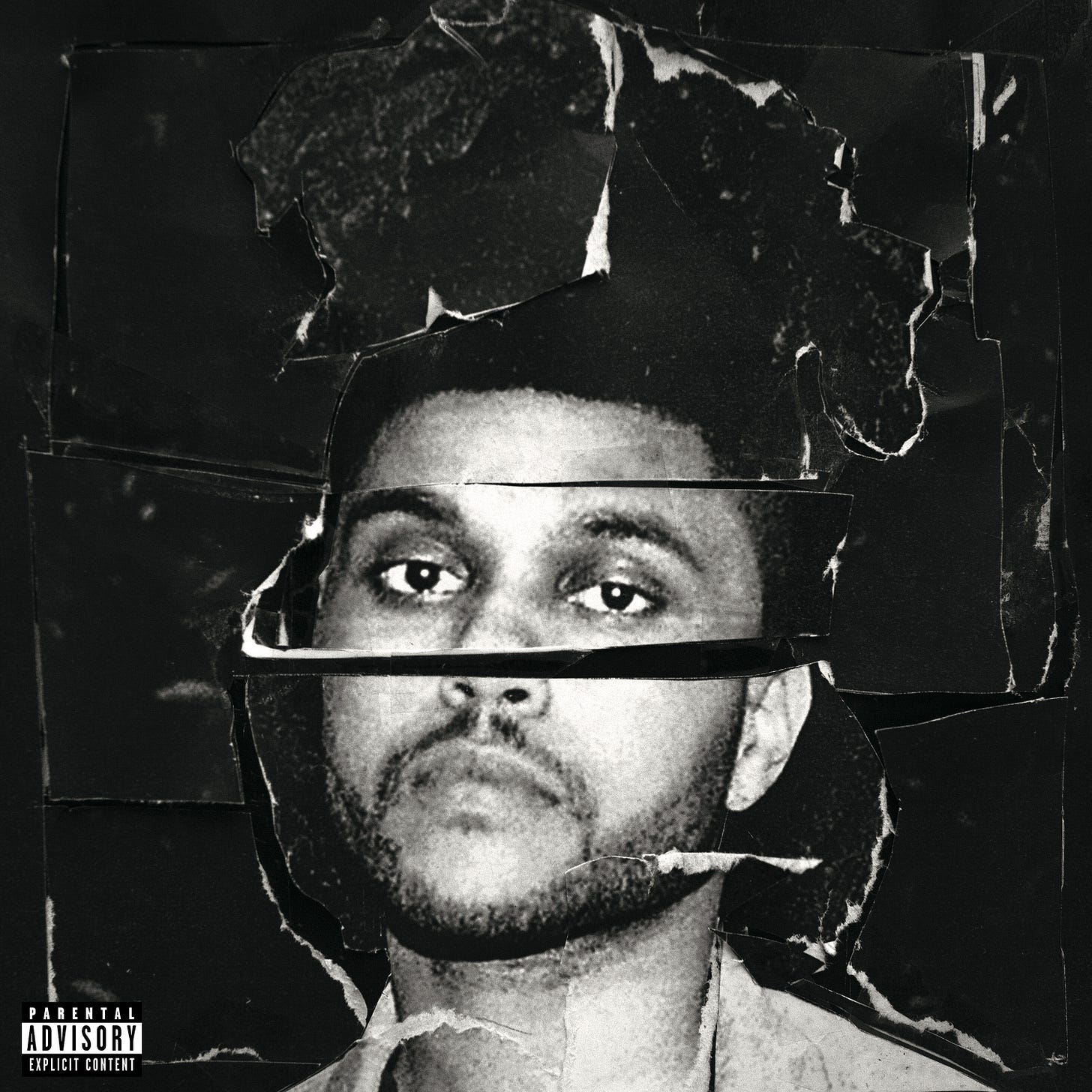

Milestones: Beauty Behind the Madness by The Weeknd

The Weeknd made Beauty Behind the Madness a dark mirror of contemporary pop stardom. We’re drawn to look at our own reflections in it, warts and all, even if we’re not sure we like what we see.

Upon Beauty Behind the Madness, Abel Tesfaye (the man behind The Weeknd) was at a crossroads. He is a cult hero of the dark Toronto R&B underground on the cusp of global pop superstardom. The result was a record that finds Tesfaye straddling two worlds, trying to “cash in” on his established persona as a “dead-eyed hedonist” without losing the sinister allure that built his early mythos. The album’s very title hints at this duality, beauty paired with madness, and throughout its 14 tracks, Tesfaye’s angelic, choirboy voice soars over decadent soundscapes, elevating his tales of sex, drugs, and despair even as it exposes the limitations of his “bad-guy” persona. Ten years on from its release, BBTM still compels and discomfits in equal measure, as a sleek, chart-topping pop record that dares his fans to find the humanity (or lack thereof) behind the veneer of fame, fortune, and nocturnal excess.

If his earlier work could be unsettlingly graphic, recall the disturbing crew-love scenario of “Initiation” or the infamous, explicit boasts of 2013’s Kiss Land, here Tesfaye has largely sanitized his art for mainstream appeal. The production is brighter, the hooks bigger, and the most predatory, explicit elements are toned down or camouflaged in pop polish. This clever sleight-of-hand makes BBTM feel at times like a Trojan horse, aka the seductive Top 40 ear candy on the surface, smuggling in the Weeknd’s slyly toxic worldview underneath. Familiar tropes from his catalog remain intact—the bleary 4 AM decadence, the sense of love as “pointless,” the nocturnal appetite for pleasure without commitment—but now they’re couched in songs catchy enough to dominate radio. The challenge, of course, is that by giving his shadowy shtick a blockbuster makeover, Tesfaye risks highlighting how one-dimensional that shtick can be. When a singer delivers lines about emotional emptiness with such grandiose conviction, over such slick beats, the effect borders on self-parody—yet it’s also weirdly convincing. The Weeknd sells moral decay with a straight face, daring you to question if he’s in on the joke or not.

Tesfaye wastes no time telegraphing his character’s philosophy. Over dramatic, swelling instrumentation on the first track “Real Life,” he croons in his signature high register, “Tell ’em this boy wasn’t meant for lovin’.” This blunt rejection of love as an ideal is the thesis statement for the Weeknd’s persona on the album. For Tesfaye’s character, love is futile and feelings are anathema; instead, there’s an endless night of “cocaine and meaningless sex” fueling him, a lifestyle so empty that even he finds no real pleasure in it anymore. This persona—a near-sociopathic hedonist singing in the “highest, saddest voice ever to come from a compulsive womaniser”—was cultivated on his 2011 mixtapes and 2013 debut. Back then, the Weeknd presented as a mysterious figure lost in a twilight world of casual hookups and druggy dissipation, numbing his emotions with misogyny and substances. In Beauty Behind the Madness, that character is fully in the spotlight, and Tesfaye must reckon with how to keep him compelling.

Nowhere is this uneasy marriage of lush production and lurid content more evident than on “Acquainted,” one of the album’s standout mid-tempo tracks. Built on a moody, melancholic piano loop and misty synth ambiance, it sounds at first like a romantic slow jam, until you listen closely. Tesfaye pointedly avoids the word “love” throughout the song, instead offering the most tepid of labels for intimacy: “Girl, I’m so glad we’re… acquainted.” The pause says it all; he cannot even bring himself to call this attachment a relationship. The trope of nocturnal hedonism courses through the album’s veins, linking tracks as disparate as the upbeat smash “Can’t Feel My Face” and darker cuts like “The Hills.” On BBTM, nighttime is when Tesfaye’s narrator thrives, or perhaps more accurately, when he survives in nihilistic fashion. Even the album’s lone outright pop banger, the Max Martin-produced “Can’t Feel My Face,” disguises its subject matter (cocaine and dependency) in funky MJ-esque grooves. In “The Hills,” Tesfaye details a clandestine 5 AM affair with his signature mix of menace and melancholy, admitting over thunderous bass that “when I’m fucked up, that’s the real me,” it’s a cry for help.

By the time he reaches “Dark Times,” his duet with Ed Sheeran, Tesfaye almost sounds resigned to his fate as a doomed anti-hero. Over twangy, reverb-soaked riffs, both singers confess to their worst impulses when night falls. Tesfaye, ever the self-styled villain, intones that “in my dark times,” he’s a terror to love, even conceding that “only my mother could love me for me” at his lowest. Even as the song’s harmonies swell, almost beautiful in their sorrow, the content remains bleakly self-destructive. The Weeknd’s persona is laid bare here, not a glamorous libertine, but a man in a bar at last call, bloodied and alone, fending off real connection because he’s convinced he doesn’t deserve it. A prime example of tricking us into sympathy for its anti-hero is “As You Are,” one of the album’s smoothest, most deceptively tender moments. With its synthetic ‘80s-style production, gentle drum machine pulses, and a warm bath of retro keyboard chords, “As You Are” could almost be a lost Phil Collins ballad. Tesfaye’s vocals are silky and pleading; the track’s chorus invites a lover to reveal her broken heart and promises, “Baby, I’ll take you as you are.”

There are also moments where cracks in the armor show, instances of real self-doubt and introspection that complicate his once one-dimensional persona. One such moment is the song “Tell Your Friends.” On the surface, this is a triumphant anthem of self-assurance: built on a warm, swaggering soul sample (courtesy of producer Ye), “Tell Your Friends” has a head-nodding groove and an almost celebratory vibe. Tesfaye uses the track to “commemorate” his success, essentially telling listeners (and haters) to go spread the word of his decadent lifestyle. With a palpable smirk, he boasts in the opening lines, “I’m that nigga with the hair, singin’ ’bout poppin’ pills, fuckin’ bitches, livin’ life so trill.” It’s a defiantly hedonistic mission statement, the Weeknd doubling down on his reputation and making no apologies for it. Yet if this is bragging, it’s bragging with a purpose. Between the catchy hook (“Go tell your friends about it”) and the verses, Tesfaye slips in autobiographical fragments that hint at the emptiness behind the excess. He recalls being “broken and homeless” in his teenage years, wandering the streets before all the fame. He even shares a morbid anecdote about a family tragedy: “My cousin said I made it big and it’s unusual/She tried to take a selfie at my grandma’s funeral,” he notes dryly, exposing how surreal and isolating his celebrity has become.

The most haunting self-examination arrives in “Prisoner,” Tesfaye’s much-anticipated duet with Lana Del Rey. Lana, pop’s queen of glamorous melancholy, proves an inspired foil for the Weeknd. Their collaboration plays out like a dark mirror duet, two characters recognizing their addictions and emptiness in each other. Over a slow, ethereal beat that sounds like it’s drifting through a smoky L.A. night, the pair trade verses about being unable to escape their vices. “I’m a prisoner to my addiction, I’m addicted to a life that’s so empty and cold,” they confess together in the chorus. In that moment, Tesfaye finally articulates the hollowness that has underlain all of his partying and promiscuity. The admission is stark: he’s not just a casual sinner having fun; he’s trapped in this lifestyle, and he knows it’s killing him. The presence of Lana Del Rey, whose own artistic persona is that of a doomed starlet forever drawn to darkness, elevates the song to a kind of theatrical soul-searching. It’s as if the Weeknd has met his match, a female counterpart who embodies the same glamorous despair he does. Their voices entwine beautifully, Lana’s breathy drawl and Abel’s aching tenor, underscoring the forlorn romance of two addicts in love with their downfall. The duet format also forces Tesfaye into a dialogue, rather than the monologues he usually delivers.

After such lows and fleeting highs, BBTM closes with “Angel,” a grand, cinematic ballad that serves as an epilogue for the album’s emotional journey. Over hymn-like piano and a children’s choir swell, Tesfaye dramatically wishes an ex-lover well, repeating “I hope you find somebody to love” as if he knows he himself will never be that somebody. It’s a surprisingly sentimental send-off from an artist who spent much of the record insisting he wasn’t capable of love. The gospel undertones and the presence of a literal angelic choir make “Angel” sound almost like a plea for salvation. However, true to form, the Weeknd frames it in a self-lacerating way: he positions himself as beyond saving. He lets this “perfect woman” go, perhaps because he knows he would ruin her, or because he deems himself unworthy. It’s an ambiguous ending that leaves the listener with a mix of relief and sadness. Tesfaye’s bad-boy persona remains fundamentally intact; he hasn’t transformed into a hero, but we’ve seen flickers of conscience and longing that weren’t there before. The madness still swirls, but the beauty (be it in the form of genuine emotion or just gorgeous production) has shown through the cracks.

The album’s juxtaposition of excess and emptiness, fame and authenticity is even more relevant now. Tesfaye’s influence on the sound of pop and R&B only grew in the years after 2015, as did his fame. The template he perfected here—brooding, narcotized R&B with pop polish and a bad-man persona crooning about sin—became a blueprint for countless artists straddling the line between urban music and mainstream charts. “The Hills” and “Can’t Feel My Face” remain modern pop classics, their hooks as addictive as ever. And the emotional conflicts Tesfaye explored on BBTM, the tension between persona and person, between hedonistic thrills and the ache for something real, continue to captivate because they feel authentic to the public image he’s built. There’s a reason listeners were drawn to the Weeknd: he offered a peek behind the curtain of celebrity excess, revealing the rot and loneliness underneath the glamour. On this album, he packaged that dark truth in alluring sounds, effectively pulling us into the contradiction. That spell still works. When Abel sings of not being able to feel his face from the high, or of being the life of the party who’s dead inside, it resonates as the anthem of a decadent era with a hangover.

Yet, there is also an argument to be made that the thrill of the Weeknd’s dark persona has diminished somewhat with time. Part of the initial excitement of Beauty Behind the Madness was the sheer audacity of its perspective. He was an R&B singer with the voice of an angel, unabashedly portraying himself as a devil, a “monster” of R&B who subverted the genre’s smooth-talking lover archetype by exposing the emptiness and misogyny often lurking beneath. It was a novelty to hear such depravity sung so beautifully. Four years on, however, Tesfaye’s nightlife-vampire shtick is no longer shocking; it’s his established brand. As years go by, we have heard him revisit these themes on subsequent projects, and the rest of the pop world has also caught up to the moody, late-night vibe he helped popularize. Tesfaye himself seemed to recognize this, as his later albums would explore new sounds and slightly more vulnerability. In hindsight, Beauty Behind the Madness stands as a transitional record, the moment the Weeknd brought his darkness into the mainstream light. On the one hand, that commitment gives the record a compelling unity of character; on the other, it means some songs feel emotionally monochromatic once the initial intrigue wears off.

The album is a document of an artist peering over the edge of mega-fame, trying to reconcile the “madness” of his well-cultivated debauchery with the “beauty” of broader musical ambitions, and, maybe, the beauty of fleeting honest emotion. That push-and-pull is what makes re-listening a rich experience. You can still lose yourself in the glossy throwback thump of “Can’t Feel My Face” or the gothic chill of “The Hills,” and you can still discover new shades of meaning in Tesfaye’s lyrics – be it a particularly passive-aggressive turn of phrase in “As You Are” that you hadn’t noticed, or the way his voice cracks just slightly on “Angel,” betraying real hurt behind the bravado. Suppose the thrill of the Weeknd’s darkness has dulled somewhat through repetition. The beauty and the madness are intertwined, and that entanglement continues to captivate—a little less shocking now, perhaps, but no less intriguing in its complexity. In sparing no detail of his nocturnal escapades while daring to wonder what it’s all worth. And that uneasy thrill, however tempered by time, hasn’t entirely faded yet.

Great (★★★★☆)

Truth pouring through your writing.