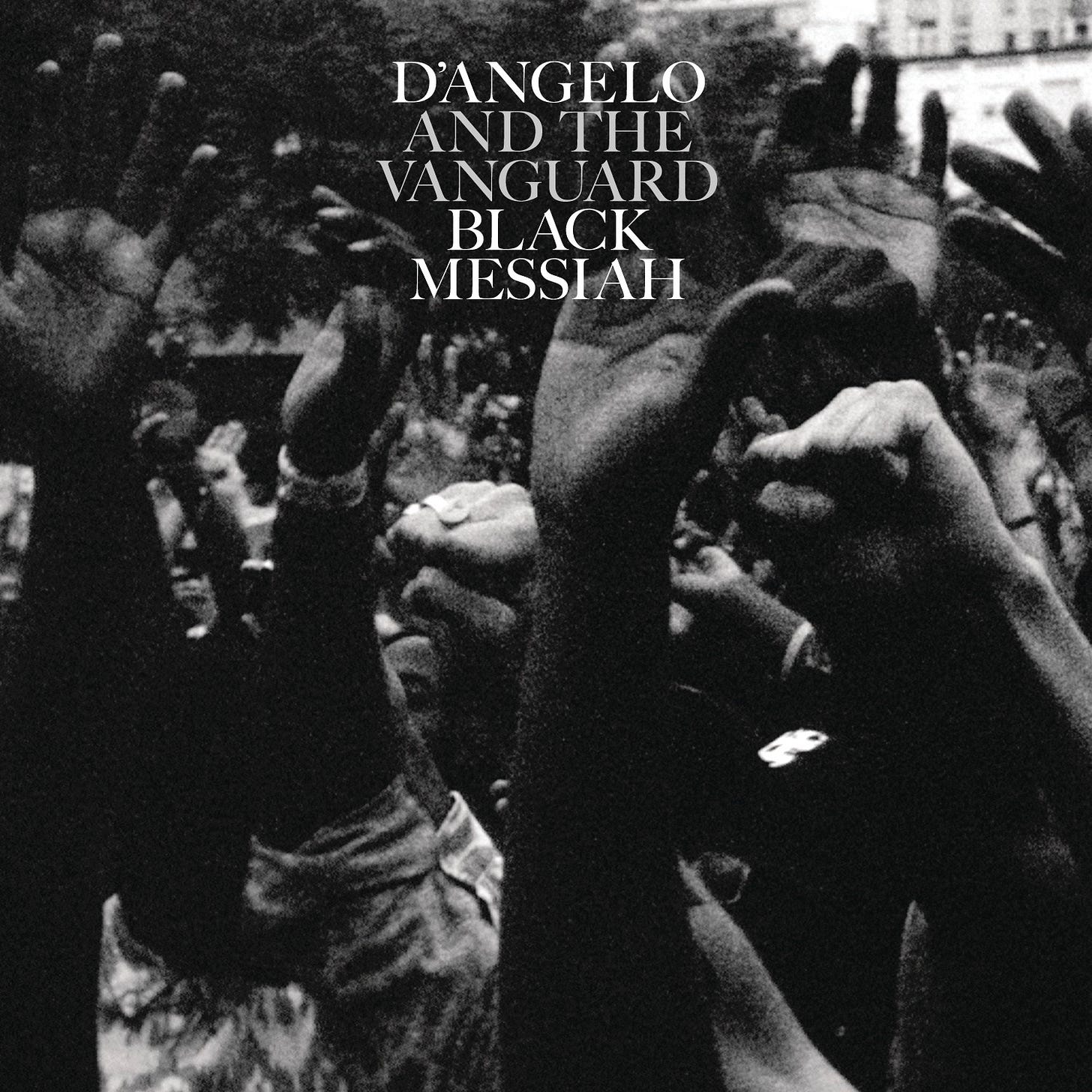

Milestones: Black Messiah by D’Angelo and The Vanguard

After fourteen years, D’Angelo pulled a Beyoncé and released his third album out of nowhere, which came out in the right place at the right time, mixing soul, funk, R&B, and rock.

“Black Messiah is a hell of a name for an album. It can be easily

misunderstood. Many will think it’s about religion. Some will jump to the

conclusion that I’m calling myself a Black Messiah. For me, the title is

about all of us. It’s about the world. It’s about an idea we can all aspire to.

We should all aspire to be a Black Messiah. It’s about people rising up in Ferguson and in Egypt and in Occupy Wall Street and in every place where a community has had enough and decides to make change happen. It’s not about praising one charismatic leader but celebrating thousands of them.

Not every song on this album is politically charged (though many are), but

calling this album Black Messiah creates a landscape where these songs

can live to the fullest. Black Messiah is not one man. It’s a feeling that, collectively, we are all that leader.” — D’Angelo

D’Angelo debuted with Brown Sugar in 1995. After five years, Voodoo followed. Fourteen additional years elapsed before Black Messiah, creating curiosity about what transpired in that long absence. Fourteen years constitute a substantial pause. Listeners may stray, gossip can intensify, anxiety may surface, and the artist’s resolve can weaken. Sizable gaps risk disconnecting performers from their audience. Any protracted absence transforms the upcoming project into a perceived comeback. This prompts questions: Is the artist still productive, still proficient, still consistent with the current sphere’s direction? Has the domain advanced beyond them?

Even during the hiatus, D’Angelo recorded cover versions referencing earlier inspirations and provided guest appearances. Such participation only deepened anticipation for new work originating directly from him. Behind the scenes, writing progressed. Sessions with Questlove contributed to the material. Concentrated studio time, somewhat aligning with Prince’s discipline, accumulated numerous tracks. Once D’Angelo assembled capable musicians, the collection gained clarity and direction. Prolonged efforts in the early 2010s saw older tunes thoroughly modified and new pieces formed. Grief, alcohol consumption, drug problems, a car accident, and monumental writer’s block had paralyzed this exceptional artist for years. As with M B V or Chinese Democracy, only a few believed this album would ever see the light of day. But unlike Axl’s Guns N’ Roses clone, D’Angelo’s return succeeds. The wait was more than worth it.

On Black Messiah, D’Angelo covered vocals and an extensive range of instruments, with Pino Palladino, Jesse Johnson, and Kendra Foster contributing notably. The pattern lasted four years: spend a month or more perfecting one track, then pause for about the same period, fostering enthusiasm and disquiet over the lack of a firm deadline. In response to the environment surrounding the Michael Brown Jr. and Eric Garner cases, D’Angelo advanced to the finishing stage, resulting in the surprise album’s release on December 15, 2014. Black Messiah addresses racial strife, persistent inequalities, and reverence for human existence, yet it also incorporates works focused on romantic feeling.

“Shut your mouth and focus on what you feel inside.” “Ain’t That Easy” starts with bulky feedback. A rocking guitar riff infiltrates the track and provides fertile ground for distinctly distorted funk. Completely recorded in analog, D’Angelo’s falsetto rises over a growling rhythm and faltering claps. The song has nothing in common with the sterility of much of today’s funk production. Its roots lie more with Sly and the Family Stone, as well as Parliament and Funkadelic—the P-Funk collective, which also includes co-author Kendra Foster.

In the latter group, “Really Love” unfolds at a gentle rate, while “Sugah Daddy” enters swiftly, fueled by rhythmic drive and bold horn lines. At the same time, “Ain’t That Easy” and “The Door” confront troubled dynamics between individuals through funk-inflected structures. In addition to collective issues, Black Messiah addresses pressing dilemmas on multiple fronts. “Till It’s Done (Tutu)” acknowledges ecological and existential questions without excess. “Prayer” applies a spiritual perspective, placing D’Angelo’s clear voice against anxious percussion, prompting thoughtful assessment, and implying that renewed effort can follow mistakes.

On the personal side, “Betray My Heart” articulates dependable affection, setting a stable melodic core. “Another Life” conveys attachment constrained by current limitations yet aiming for eventual achievement. Each detail maintains coherence, lending substantial meaning. “1000 Deaths” then presents forthright commentary on systematic distortions. It incorporates formidable percussion and excerpts from Khalid Abdul Muhammad and Fred Hampton. The track begins with a charismatic priest who preaches about the true Messiah—not the white man hanging on today’s cross, but the Jesus of the Bible, “with hair like lamb’s wool, a black revolutionary Messiah.” A relentless and hostile anti-groove underpins the story of a soldier going into battle.

“Send me over the hill/I was born to kill.” It’s a dark, loud, and ugly monster peppered with anger. Forwards and backward, the bass sways toward a guitar solo that resembles an agonizing final singe. Their statements urge direct engagement, while D’Angelo’s allusion to Shakespeare underscores that continuous avoidance leads to repeated diminishment, whereas decisive confrontation grants authenticity. Observers have connected these elements to There’s a Riot Goin’ On and What’s Going On, situating the album within a lineage of socially engaged recordings.

Under the surface, direct insight does not always appear. Some lyric passages drift into obscurity behind thick vocal textures. Such concealment does more than confuse; it insists that the listener pay attention, commit effort, and approach meaning with intention. Refer to “The Charade” for an illustration of this process. Its narrative comments on the challenges Black Americans confront in their fight against deep-rooted prejudice. A sitar and a psychedelic guitar, which not only remind us of Eddie Hazel but also accompany his grim words throughout the track, reminiscent of a cross-minded outtake from Prince’s Diamonds and Pearls album. In those brief verses, D’Angelo conveys a grim reality and a continuing demand for recognition and fundamental fairness. Each syllable presses for understanding and refuses silence.

Seamlessly, Black Messiah connects to Voodoo. If you want to do some pea-counting, you could note that the long player, in kind and sound, could have appeared ten years ago, as it seems a bit out of time. However, he compensates for this flaw with his clumsiness and extravagance. D’Angelo never looks for the easy way; instead, he scrutinizes corners and edges for hidden secret passages. In 2014, D’Angelo is the musician Prince would like to be today.

Standout (★★★★½)

love this