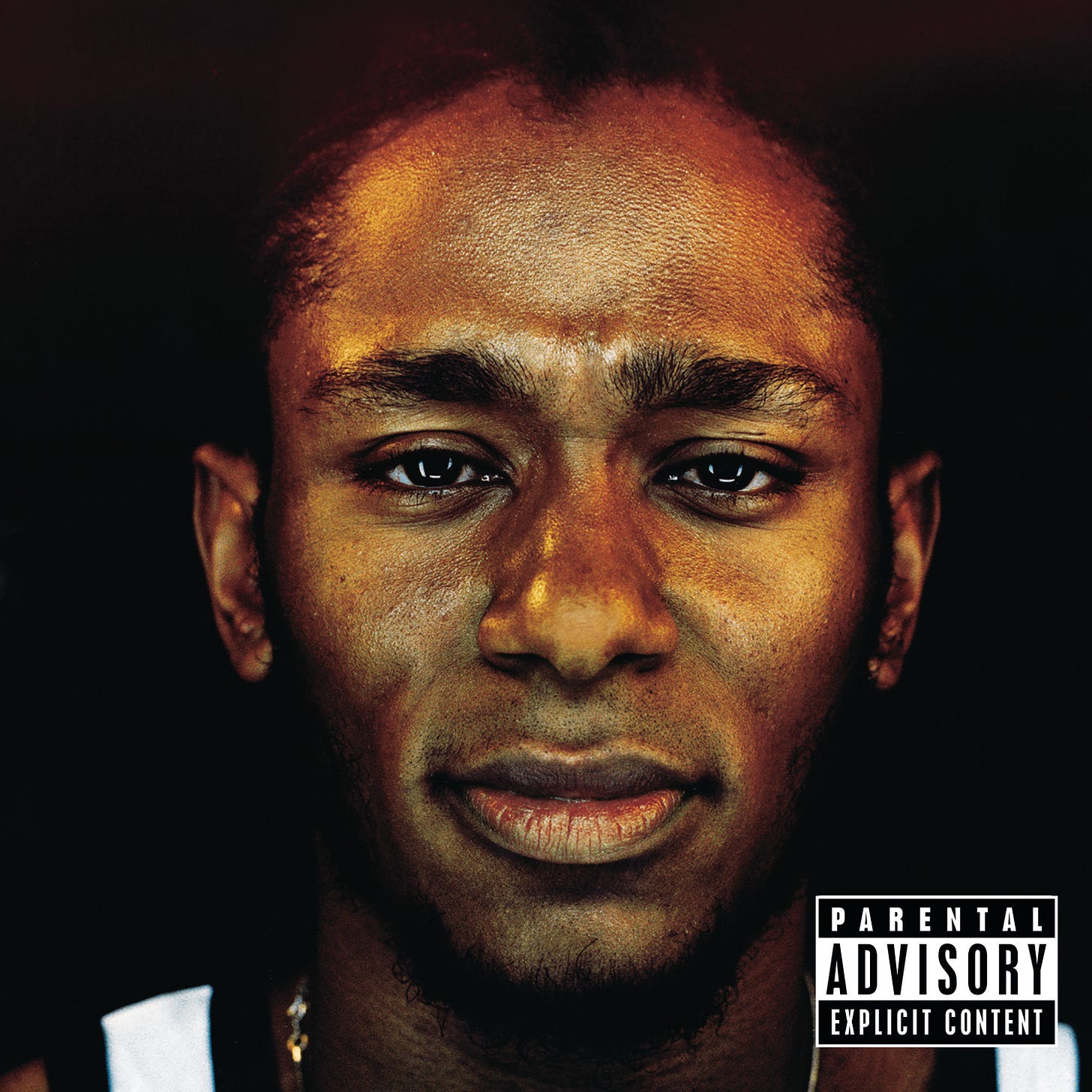

Milestones: Black On Both Sides by Mos Def

With claim, party jam, and social criticism, Mos Def heals the wounds with this phenomenal debut LP.

At the conclusion of the 90s, hip-hop was far from extinct but rather grievously wounded. This was mainly due to the escalating rivalry between the Rap factions based in New York and the West Coast, a feud whose tragic climax marked the premature demise of two tremendously gifted artists, 2Pac and Biggie. Their erroneous engagement in this immature gang conflict was a loss deeply felt across the industry.

The aftermath dissuaded the further spread of hateful disses and unnecessary sacrifices, leading to an appeal for a more amicable sound. It was Sean “Puff Daddy” Combs who answered the call, the one who ironically played a vital role in the feud mentioned above. He championed a gentler, tonally nuanced version of hip-hop, catalyzing its commercialization with polished pop productions. Nonetheless, his ambitious pursuit heralded a fresh schism in the scene, this time non-violent but no less divisive.

On the other side of the chasm, young underground artists such as Mos Def alienated themselves from the ostentatious display of wealth in music videos. Raised amid the modest backstreets of Brooklyn, Mos Def’s musical initiation and upbringing were deeply entrenched in the cultural ethos of the native tongues. An artist guild founded by the likes of A Tribe Called Quest and De La Soul during the late 80s, their focus on cultural storytelling and imparting the depth of black history took precedence over gangsta posturing or promoting a hedonistic lifestyle.

Stepping forth as the latest marvel to emerge from the New York underground in 1998, Mos Def, in collaboration with Talib Kweli, sparked interest in the industry as a Black Star and was soon hailed as a promising successor to Nas and his debut Illmatic. The immense expectations and pressure bestowed upon him were counterbalanced by the fellowship with promising producers and the repertoire of an industry veteran: DJ Premier.

The robust thought process regarding the status of hip-hop as a genre was revealed with the launch of his debut album, Black On Both Sides, in October of 1999. The opening track, “Fear Not a Man,” manifests his perception of the precarious state of hip-hop. His prognosis for the future of hip-hop in the 90s is articulated clearly: “You know what’s gonna happen with hip-hop? If we smoked out, hip-hop is gonna be smoked out/If we doin’ alright, hip-hop is gonna be doin’ alright.”

His musical breadth extends from Fela Kuti to German Krautrock. He concludes with a 699-word assertion to the global hip-hop culture: Disdain is futile, you are an integral part of the culture, and you have the power to enhance it. This is a perspicacious perspective from a young mouth speaking with wisdom beyond his years. His message: each one, teach one. His mentors, such as Q-Tip, could not be more gratified.

The early lessons in the power and potency of words as a weapon were instilled in Mos Def in the Lyricist Lounge, a vibrant open mic event in New York. This event was a hotbed of not just hip-hop talents but also where profound slam poets like Saul Williams honed their craft. His words demonstrate a political awareness as refined and grown-up as his wisdom. In the soothing cadences of jazz hip-hop, captured within “UMI Says,” he elaborates:

“Put my heart and soul into this

I hope you feel me

From where I am, to wherever you are

I mean that sincerely.”

The recurring chant in the bridge, “All Black people to be free/That’s all that matters to me,” is reverberated like an invocation. The phrase repeats as if all the scarred souls tarnished by the history of slavery and repression flow through his body, seeking emancipation through his voice.

Mos Def harbors a strong dissent against the cultural assimilation by the white demographic. In his track “Rock N Roll”, he makes his stance clear by stating:

“I said, Elvis Presley ain’t got no soul, Chuck Berry is rock and roll

You may dig on the Rolling Stones, but they ain’t come up with that style on they own.”

In an unusual departure from the laid-back tone of the rest of the album, he bellows into the microphone, “All towns get your punk ass up,” in a classic New York hardcore manner. Although it is a potent statement acknowledging the significant influence of the Bad Brains on hardcore, it remains a deviation from an otherwise harmonious album.

In the style of his initial laid-back jam sessions in Brooklyn, the rhythmic continuity and tonal uniformity rules in this concept album that explores Black identity. The listener’s mind is held captive, and the head ever willingly sways to the thrilling merger of jazz and funk, among other genres that exemplify Black music. Ubiquitous live recordings lend a hearty authenticity; all artificiality dissolves, leaving a rich analog warmth provided by instrumental classics such as the Fender Rhodes. Of particular note, “Mr. Nigga” brims with an energy so potent it echoes a Funkadelic concert’s live recording. In these moments of ecstasy, whether it’s sweat or tears that trail over the listener’s face, contemplating the issue of racism becomes secondary.

In 1999, hip-hop bore the brunt of an assault, leaving it vulnerable and dazed. But, the Renaissance began with Black On Both Sides, Mos Def’s audacious rebirth, that myriad rappers echoed within the conscious rap guild. Amongst his audience was a young lad from the West Coast, who persistently connected with the album and, years later, offered his own tribute with To Pimp a Butterfly, skillfully weaving between solemnity, peppy rhythm, and social critique reminiscent of his idol.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)