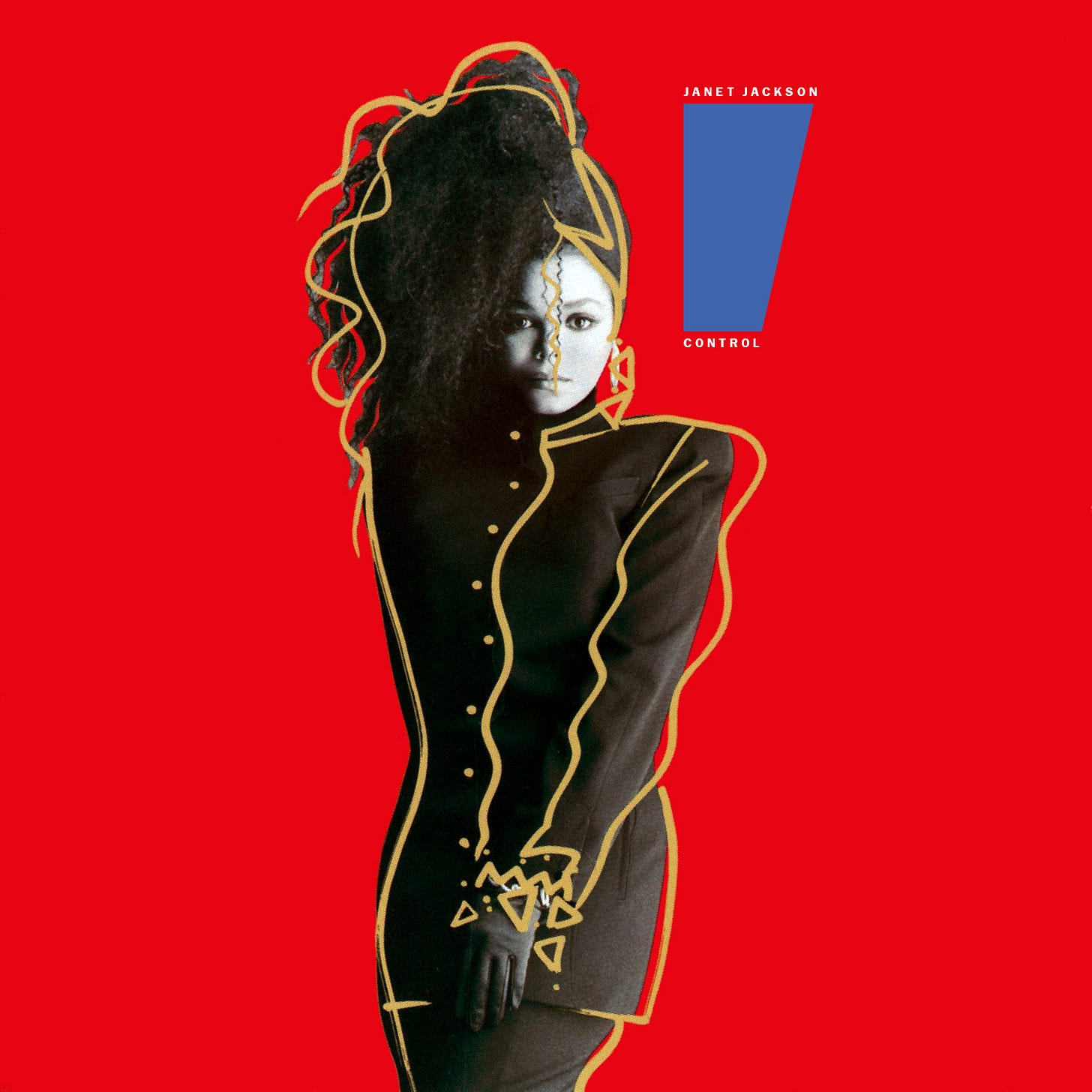

Milestones: Control by Janet Jackson

Janet fired her father, annulled her marriage, and flew to Minneapolis. Six weeks later she had built the machine that would define her. Nine songs about work, boundaries, desire, and self-worth.

When Janet Jackson arrived at Flyte Tyme Studios in Minneapolis during the summer of 1985, she ran outside to make a snow angel. Jimmy Jam remembered this detail decades later, the image of this nineteen-year-old from Encino, fresh off firing her father and annulling her marriage, flopping into a Minnesota drift like a kid let out of school early. She had come to record with two former members of Prince’s band The Time, a pair of producers who had been dismissed after missing a concert while finishing a session for the S.O.S. Band. The pairing made sense on paper. Janet was a Time fan, Jam and Lewis needed work. But the alchemy that followed required something beyond professional convenience. Before tracking a single vocal, the three of them spent a week just talking.

Those conversations gave Jam and Lewis what they needed. Janet opened up about her controlling family, about the two albums her father had steered into commercial indifference, about the DeBarge marriage that had dissolved almost as quickly as it began. Her previous records had been handed to her like homework assignments. Giorgio Moroder, Rene and Angela, Jesse Johnson. Talented people, all of them, but none of them interested in asking Janet what she actually wanted to say. Jam put it plainly. The motivation wasn’t there because singing wasn’t her idea. Now she was ready to make it her idea. The producers required total control of the sessions, no bodyguards, no handlers, no Joe Jackson hovering with suggestions. They recorded everything on their turf, far from Hollywood, working evenings because Minnesota summers deserved daylight.

The first song they cut was “He Doesn’t Know I’m Alive,” a ballad with high notes at the end that let Jam and Lewis hear what she could do. She nailed it. That session told them they could push her anywhere. The tracks they built after that could have been for a male artist or a rapper. Aggressive, percussive, built on the Ensoniq Mirage’s distinctive triplet swing. Their bet was that Janet had the attitude to sell material this confrontational. The bet paid.

“Nasty” landed in her lap after an incident outside her Minneapolis hotel. A group of men had harassed her on the street, and instead of retreating to the protection of her producers, she backed them down herself. The emotional residue of that confrontation became the song’s spine. “They were emotionally abusive. Sexually threatening,” she recalled. “That’s how songs like ‘Nasty’ and ‘What Have You Done for Me Lately’ were born, out of a sense of self-defense.” Jam wrote and played the keyboard arrangement. Janet handled accompaniment. When she first sang it, she used the high, airy register audiences knew from television. Terry Lewis asked her to try it an octave lower. She resisted. It sounded weird to her. The next day, they played her the results. The look on her face, Jam said, was the best look an artist could ever give you, that mixture of surprise and satisfaction. That lower register became her new signature, a delivery that could snarl and bite instead of merely pleading.

The album’s title track opens with a spoken monologue that doubles as a mission statement. Janet recites her credentials. When she was born, when she started school, when she started acting. Then she declares that she’s been let out of a cage and nobody’s shutting the door again. The herky-jerky production underneath starts and stops like a machine learning to walk, all stutter and swagger. Jam and Lewis built their sound from drum machines and synth bass, adding new elements as each song’s structure demanded. The simplicity was the point. Two foundational ingredients, then everything else arranged around them like furniture in a bare room.

“What Have You Done for Me Lately” almost didn’t make the record. Jam and Lewis had been saving it for their own record, but John McClain, the A&M executive who championed Janet, kept insisting they needed one more single. They played him a cassette of demos intended for their project, and he pointed at that track immediately. Started her career, ended ours, Jam later joked. The song kicks off with one of Janet’s soon-to-be-trademark interludes before launching into a kiss-off so direct it barely needs interpretation. Her ex gave her nothing but grief, and she’s done pretending otherwise.

What separates Control from its descendants is how little the production cushions Janet’s demands. The beats hit like fists on a table. The synth-horn arrangements on “When I Think of You” burst in with the frenzied energy of travel brochures. See the world! Spend money! Make the deal! Janet rides the track with girlish giddiness, her only true surrender to uncomplicated joy on the record. “The Pleasure Principle” pivots toward electro-funk, its lyrics about self-reliance after romantic disappointment, but the groove invites movement rather than moping. Paula Abdul trained Janet’s dancing for the videos, and you can hear the choreography built into the music itself, the way certain phrases demand physical response.

“Let’s Wait Awhile” might seem like a concession to softness, a ballad about delaying physical intimacy until the emotional foundation solidifies. Janet sang it as a promise she intended to keep. “I’ll be worth the wait,” she tells her partner at the song’s close, and her tremulous voice makes the vow sound fragile and fierce at once. Critics who dismissed her thin tone missed how perfectly that hesitance fit the material. You don’t want a powerhouse belter selling abstinence; you want someone who sounds like waiting actually costs her something.

The album closes with “Funny How Time Flies (When You’re Having Fun),” a slow-burn seduction that opens with a French-spoken interlude and never quite arrives at its destination. Janet whispers and coos for nearly six minutes, and the track bears clear resemblance to her brother Michael’s “The Lady in My Life.” She told VH1 she was just a baby when she recorded it, that the song gave listeners a glimpse into a world they’d see much more of later. The sequencing feels almost perverse after the message discipline of the preceding tracks. All that declared independence, all that refusal to compromise, and then this languid submission to pleasure. The juxtaposition works because Janet had earned the right to her own contradictions. She could be the woman who backed down street harassers and the woman sighing into a pillow, and neither mode canceled the other.

Jam and Lewis won Producer of the Year at the Grammys, the only award the album took home despite four nominations. The critical consensus at the time credited their production innovations while sometimes questioning whether Janet herself was the star or merely the vessel. This misread the collaboration fundamentally. Janet’s phrasing sits against those crowded percussion tracks like a blade against a whetstone. The thinness people complained about gave her an advantage nobody recognized. She could slide through spaces that would have swallowed a bigger voice, could shift from aggression to vulnerability within a single phrase without the seams showing. Terry Lewis called her fearless, relentless, beautiful. A beautiful texture, very in control. Her vocal takes included breaths, sighs, laughs that any other producer would have scrubbed. Jam and Lewis left them in because those were the personality markers, the proof that a human being was making these sounds rather than an automaton programmed by her famous family.

Joe Jackson attended one meeting during the making of the album. He told Jam and Lewis not to make his daughter sound like Prince. Don’t make her risqué. They smiled and nodded and then spent six weeks doing exactly what they wanted. Janet emerged from Minneapolis sounding nothing like her previous self and nothing like Prince either, despite the Minneapolis connection and the funk ancestry. She sounded like someone who had figured out what she wanted and built the machine to deliver it.

The songs on Control address work, boundaries, self-worth, and desire with an almost clinical precision. Janet demands to know what her partner has contributed lately. She refuses men who mistake her availability for accessibility. She promises her body on her own terms, in her own time. She admits that pleasure makes hours vanish. None of these sentiments were new to pop music in 1986, but the packaging was. Here was a Black woman from one of America’s most famous families claiming autonomy not by rejecting her lineage but by insisting she could determine what it meant for her. The family name remained on the album cover. She just decided what it would stand for now.

The production innovations Jam and Lewis pioneered here would ripple through the next decade of R&B and pop. Teddy Riley built new jack swing from the rhythmic DNA of “Nasty.” Janet herself would radicalize the formula on Rhythm Nation 1814, turning militant and didactic in ways Control only hinted at. Later albums would find her more experimental, more explicitly sexual, sometimes more interesting track by track. None of them would feel as complete as this one. The nine songs cohere not because they share a theme but because they share a protagonist working out her relationship to her own desires in real time.

Janet Jackson said she wanted the album to express exactly who she was. “It’s aggressive, cocky, very forward.” She had taken control of her own life, and this time she was going to do it her way. The snow angel she made outside Flyte Tyme melted within hours. The record she made inside those walls kept its shape.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)