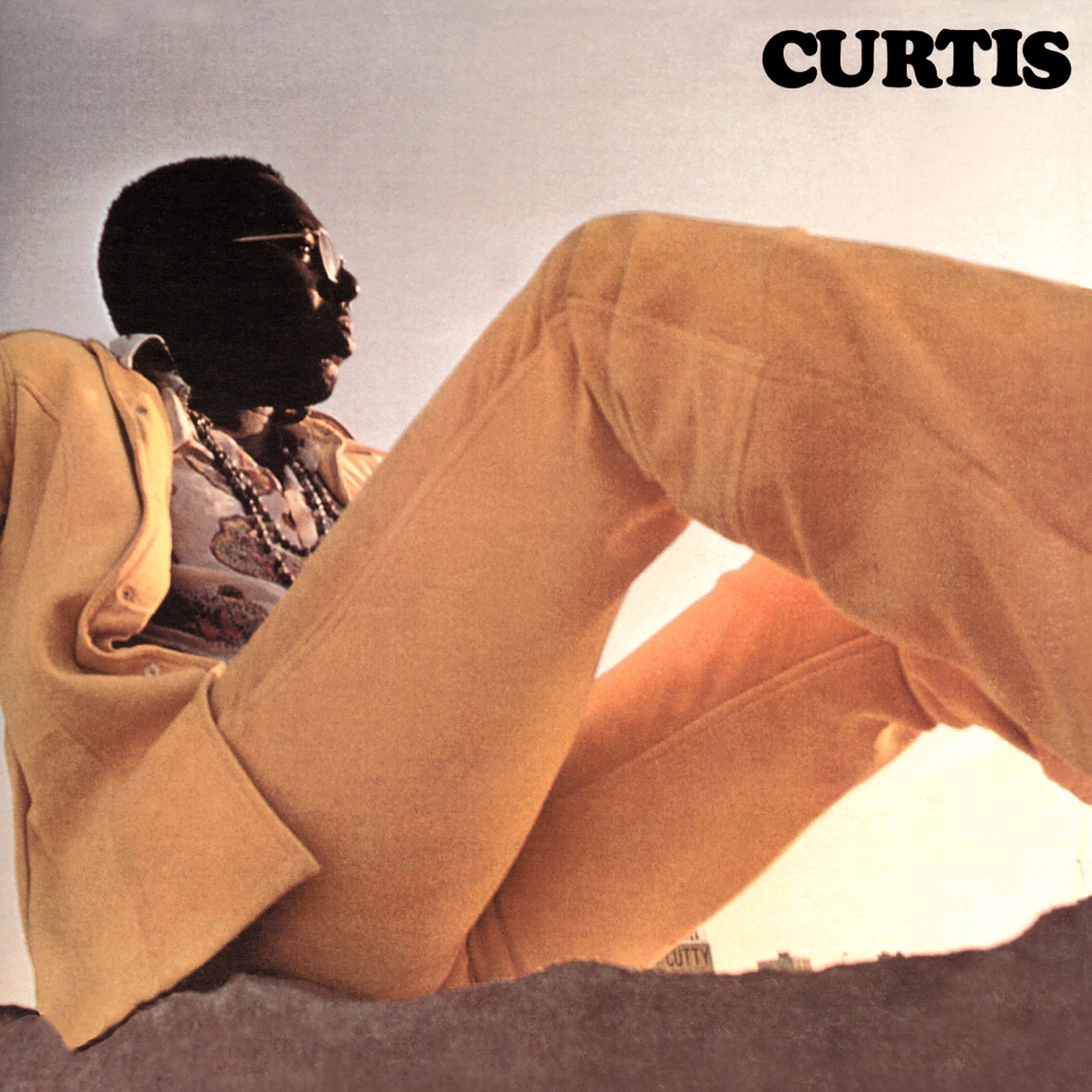

Milestones: Curtis by Curtis Mayfield

Curtis opened up a new world for soul music, and for that we’re all the better—or as Mayfield might say, we’re moving on up.

In September 1970, amid a turbulent America grappling with civil rights struggles and cultural upheaval, Curtis Mayfield released his debut solo album, Curtis—an album so ambitious and cohesively realized that one critic deemed it “practically the Sgt. Pepper’s album of ‘70s soul.” Just as the Beatles’ opus had expanded the possibilities of rock a few years prior, Curtis opened soul music to “much bigger, richer musical canvases” than ever before. This landmark album was the culmination of all of Mayfield’s years of experience—an apotheosis that pulled together a lifetime in music and the immediacy of 1970’s social concerns into one powerful statement. The former Impressions frontman had long been a quiet pioneer of socially conscious soul; with Curtis, he seized the moment to fuse lush old-school R&B elegance with urgent new funk and psychedelic sounds, crafting music at once steeped in tradition and daringly progressive. More than half a century later, Curtis endures as a visionary work that not only reflected its times but helped shape the musical and political currents that followed.

It’s clear Mayfield was stepping out of the polite pop-soul mold and into bolder territory. The album opens with a menacing fade-in of conga drums and distorted bass, soon joined by Mayfield’s voice intoning a provocative warning: “If there’s a hell below, we’re all gonna go.” In “(Don’t Worry) If There’s a Hell Down Below, We’re All Going to Go,” he adopts the fiery tone of a street-corner preacher, calling out bigotry and hypocrisy across racial and social lines. Without softening the language, he targets “sisters, brothers, whiteys, Jews, crackers”—an electrifying, controversial roll call that dares every listener to confront the nation’s twisted state. This opening salvo, delivered over a wah-wah guitar-fueled funk groove, was as startling as anything in soul music at the time. Mayfield’s high tenor glides over churning bass and swirling percussion, preaching unity and damnation in the same breath. It was a bold choice for a lead single—raw language, seven-minute run time—yet it struck a chord. With that one song, Mayfield signaled that Curtis would confront the truth of America’s turmoil head-on, delivering social commentary with unflinching candor and groove.

Though Curtis was Mayfield’s first solo LP, it was hardly the work of a newcomer. He had spent the previous decade penning and performing hits with the Impressions, and his artistry deepened with experience. In the early 1960s, Mayfield’s velvety tenor and melodic songwriting produced gentle love songs and gospel-infused ballads that lit up the Chicago soul scene. By the mid-’60s, he was also writing stirring anthems for change: “Keep On Pushing” and “People Get Ready” became civil-rights soundtracks, inspiring activists and even future presidents (decades later, “Keep On Pushing” heralded Barack Obama’s 2004 DNC speech). Mayfield was “one of the earliest artists to speak openly about African-American pride and community struggle” in popular music. Songs like “We’re a Winner” in 1967 unabashedly celebrated Black empowerment at a time when such messages could get a show canceled in the Deep South. All of these experiences—the romantic doo-wop beginnings, the burgeoning social consciousness, the triumphs and trials of the 1960s—fed the creative well Mayfield drew from on Curtis. As he later explained, the album gave him the freedom “to be more personal for myself,” exploring ideas he’d “long wanted to do” but that didn’t fit the Impressions’ image. By 1970, the gentle genius from Cabrini–Green had founded his own Curtom label and was ready to take full control of his art—a bold entrepreneurial move that set an example for Black artists asserting their independence. This would be his grand statement, and he wasn’t going to hold back.

At a lean 40 minutes, Curtis packs in a world of musical ideas and social commentary. Mayfield balances the immediacy of contemporary issues with reverent nods to classic R&B tradition, keeping the album from feeling like a polemic or a history lesson; it plays as a vibrant musical experience. Nowhere is that balance clearer than in the transition from the blistering opener to “The Other Side of Town,” the very next song. Slowing the tempo, Mayfield assumes the persona of a man mired in urban poverty, detailing despair with poetic economy. “Depression is part of my mind, the sun never shine on the other side of town,” he sings softly, painting a stark picture of ghettos divided by an invisible but palpable line. The lyrics eviscerate the reality of racial and economic segregation—hungry children, ambient hopelessness—yet his delivery is tender, almost soothing. This contrast—devastating words cushioned by a sweet, melancholic melody—shows Mayfield’s subtle power. As one observer noted, he could “cushion the blows so softly without negating the impact of the words,” using his exquisite falsetto to wrap hard truths in soulful beauty. The result moves the listener emotionally and intellectually: empathy stirred, society indicted.

That ability to marry socially charged messages with heart-rending music elevates Curtis into timeless art. Midway through Side A comes “The Makings of You,” a sublime love song that offers gentle respite from the socio-political tension. With harp glissandos and swooning strings, “The Makings of You” harks back to the sweet-soul balladry of earlier R&B. Over a plush orchestral arrangement, Mayfield’s falsetto caresses lyrics of pure devotion—a reminder that the same man who could call down fire and brimstone in one song could evoke deep romance in the next. Aretha Franklin later covered “The Makings of You,” remarking that “Curtis Mayfield is to soul music what Bach was to classical… a soul laureate and the heart and soul of a song and a people.” Placed amid fiery tracks, the song grounds the album in the classic traditions of love and melody that defined R&B’s past, even as Mayfield pushes the genre forward. That duality—topical songwriting alongside elegant romanticism—shows how Curtis bridges generations of Black music.

Side B of Curtis kicks off with its tour de force: “Move On Up.” If one song best represents Mayfield’s decades-honed talents meeting the hopeful spirit of the era, it’s this nearly nine-minute funk-soul anthem. Powered by bright, horn-laden charts and a galloping conga beat, “Move On Up” is pure uplift. Mayfield unleashes choppy rhythm guitar and a joyous brass section to create forward momentum. The track bristles with “effervescent energy that never lets up,” built to get listeners on their feet. It’s an exhortation to persevere: “take nothing less than the supreme best,” keep pushing through obstacles—the “keep on pushing” ethos extended into a new decade. Mid-song, the band drops out, then kicks back in for an extended instrumental jam—a moment some described as time standing still for a split second before the groove “demands movement from every sinew and muscle.” This dynamic arrangement—part composed song, part improvisatory jam—stretched the soul single format into something more expansive. Mayfield loved the full 8:45 album cut and initially resisted editing it; a shorter single arrived in mid-1971, and “Move On Up” made a bigger impact in the U.K. than on U.S. charts. Even so, over time, it became one of Mayfield’s signature songs and a lasting cultural anthem—ubiquitous in film and advertising and sampled decades later.

Even as Curtis reaches ecstatic heights on “Move On Up,” it stays grounded in the realities of Black American life in 1970. Perhaps the album’s most poignant social commentary comes in “We the People Who Are Darker Than Blue.” Over a restrained backdrop of muted horns, plaintive piano, and mournful strings, Mayfield begins with a soulful meditation on racial unity and self-determination. “We people who are darker than blue / this ain’t no time for segregatin’,” he sings, directly addressing divisions within communities of color. He pointedly includes “brown and yellow too,” urging Black and brown listeners to recognize common cause. Halfway through, the song transforms: around 1:50, the horns punch in with a staccato fanfare—a signal of urgency—and the band shifts into a harder, funk-driven groove. Mayfield’s honeyed vocal turns stern and impassioned. “Get yourself together, learn to know your sign,” he implores. “Shall we commit our own genocide before you check out your mind?” Across six minutes, “We the People…” moves from sorrow to anger to hopeful resolve, ending in a crescendo that suggests a brighter day if unity can be achieved. The changes of pace and tone show Mayfield’s arrangement skills and emotional intelligence as a songwriter.

In the latter half of Curtis, Mayfield continues to mix social messaging with sweetness. “Miss Black America” is a breezy, upbeat tune paying homage to Black women, likely inspired by the Miss Black America pageants that had recently emerged to celebrate African-American beauty and pride. Coming after the intensity of “Move On Up,” its positivity “oozes from every note.” Mayfield sings with evident joy and respect, offering a musical bouquet at a time when Black women were often underappreciated in society and even within the movement. The strings and horns dance playfully here, showing that his orchestral flourishes could swing lightheartedly as well as dramatize. “Wild and Free” offers another slice of uplifting soul that invokes the desire for freedom.

Throughout Curtis, he wasn’t shy about atypical instruments for soul: delicate harps, Latin percussion, orchestral strings—all folded into the mix to create striking timbres and textures. The album closes on an introspective note with “Give It Up.” After so much hope and solidarity, Mayfield turns personal, detailing the pain of a failing relationship. Over the same “delightful concoction of strings, drums [and] urgent horn blasts,” he admits, “our love is incompatible, no matter how we try.” It’s a bittersweet ending—the lone moment of pessimism on an otherwise aspirational record. By placing “Give It Up” last, Mayfield acknowledges that struggle and disappointment are part of life, even as we strive for better—a final link back to classic soul themes of love lost.

In production terms, Curtis was as groundbreaking as its subject matter. As his own producer, Mayfield “embraced the most progressive soul sounds of the era,” stretching out compellingly on extended cuts like “Move On Up” while drawing on orchestral color (especially harp) to enrich the palette. This was a conscious departure from the simpler guitar/bass/drums setups of many ’60s soul records. With arrangers Riley Hampton (an Impressions-era collaborator) and Gary Slabo, he wove disparate elements into a cohesive whole. Funky drum patterns of the sort heard in James Brown’s work sit “cheek by jowl” with sweeping strings and horns; even rhythms traceable to West African drumming find a home in the mix. Crucially, these ingredients “don’t crowd each other out”; they nestle together “as the best of friends,” creating patterns that would permeate the soul sounds of the 1970s. In essence, Curtis helped pioneer richly textured progressive soul.

Albums like Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On and Stevie Wonder’s 1970s classics would follow a similar template: socially conscious lyrics over sophisticated, genre-blending arrangements. Mayfield was at the vanguard. He wasn’t formally trained in theory, which perhaps freed him to invent unusual chord progressions and song forms. (He tuned his guitar in a unique F# tuning, lending his playing a distinctive voicing musicians found striking.) His band noted he’d sometimes write in “a terribly strange key,” and they rolled with it, respecting the idiosyncrasies. At the same time, he was a disciplined editor: eight tracks, each purposeful and tightly arranged despite the lush instrumentation. Bruce Eder of AllMusic marveled at how Mayfield “wove all of these influences, plus the topical nature of the songs, into a neat, amazingly lean whole.” For all its symphonic flourishes, the album remains lean and listenable—evidence of Mayfield’s clarity of vision as a producer.

Upon release, Curtis met commercial success and mixed critical reactions. The album topped Billboard’s R&B chart for five weeks and cracked the Top 20 on the pop albums chart, a significant crossover achievement for such an uncompromising project. Black listeners in particular embraced it; the record felt like a soundtrack to the era’s trials and hopes. Only one track, the aforementioned “Hell Below,” became a major U.S. hit single, yet few minded—Curtis was meant to be experienced as an album-length statement. One contemporary reviewer noted that Curtis “really had to be heard” as a complete work, its songs interlocking to convey a larger message. Some mainstream critics, however, didn’t immediately appreciate Mayfield’s approach. Rolling Stone’s original 1970 review infamously dismissed much of the music as “fragmentary, garbled and frustrating,” and the lyrics as “haphazardly written” strings of slogans, even poking fun at rhyming “steeple” with “people.”

In hindsight, those critiques read as tone-deaf—missing the depth in Mayfield’s vernacular poetics and rhythmic innovations. Rolling Stone eventually walked back its stance; by the 1980s, critics like Robert Christgau acknowledged that Curtis’s artistry revealed itself over time, and later assessments placed it ahead of even Super Fly in song-for-song strength. Across the Atlantic, the response was quicker: Britain’s Blues & Soul lauded Curtis as “certainly one of the most creative and personal albums” in a long while. By tackling oppression, unity, and love with such sincerity, the album transcended its era to become a perennial touchstone. Rolling Stone would go on to include it among the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and it’s frequently cited as essential in the soul canon. Far from “fragmentary,” Curtis is now recognized as one of the most cohesive artistic statements of its time.

The legacy of Curtis grew in the years that followed, influencing artists across genres and generations. In the immediate wake of its release, the fusion of funk grooves, symphonic arrangements, and social insight helped usher in progressive soul. Alongside Sly & the Family Stone’s incendiary There’s a Riot Goin’ On and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, Curtis encouraged soul musicians to think bigger—crafting albums with unifying themes and adventurous production. Stevie Wonder took note, blending uplift, political edge, and complex arrangements on Innervisions and beyond. Earth, Wind & Fire carried forward sweeping horn arrangements and hard-earned optimism that Curtis exemplified. When Mayfield scored the 1972 blaxploitation film Super Fly, he set a template for cinematic soul that countless others followed—building on the foundation Curtis had already laid: wah-wah guitars, cinematic strings, socially conscious narratives. Beyond soul and funk, the album’s influence reached reggae. Jamaican artists—from Bob Marley and the Wailers to rocksteady vocal groups—drew from Mayfield’s gospel-infused message songs and delicate falsetto. (Marley’s “One Love” borrows lines from “People Get Ready,” a direct nod to Mayfield’s ethos of unity.)

In the decades since, artists as different as Prince, Jimi Hendrix, and Jill Scott have acknowledged Mayfield’s imprint. Hendrix, though a rock icon, drew on Mayfield’s fluid, tender guitar approach; those chordal voicings and rhythm chops surface in his ballads. Prince, often citing 1970s soul influences, took cues from Mayfield’s blend of funk and social commentary; he even cut the unreleased “Born 2 Die” in a Mayfield vein after Cornel West quipped that Prince was “no Curtis Mayfield.” In R&B and neo-soul, Mayfield’s fingerprints are everywhere: Maxwell’s supple falsetto and mellow grooves, John Legend’s socially aware balladry, Raphael Saadiq’s retro-soul productions. Hip-hop kept Mayfield in the conversation, too; beyond the many samples—Kanye West’s “Touch the Sky” famously flips the “Move On Up” horns—rappers often mirrored Mayfield’s frank social critiques. The nickname “Gentle Genius” fits: music can be tender in tone yet revolutionary in impact.

Ultimately, Curtis endures not because it was merely of its time, but because it transcended its time. The album captured the anger, yearning, pride, and love of 1970 and set them to music with uncommon grace. Listening today, much of it still feels contemporary: the call for unity in “We the People…,” the demand for truth in “If There’s a Hell Below…,” the celebration of Black identity in “Miss Black America.” The blend of elegant orchestration, deep-funk rhythm, and socially conscious songwriting has proven durable. Many have followed Mayfield’s example, but Curtis retains a singular magic—sincerity in the voice, seamless integration of elements, and one artist striving to give voice to his community’s struggles and dreams. As filmmaker Andrew Young put it, “You have to think of Curtis Mayfield as a prophetic, visionary teacher of our people and our time.” Curtis is that prophecy and vision captured on vinyl—an album that taught and inspired, yet never forgot to groove. Its legacy echoes whenever an artist merges art and activism, whenever a soul song carries both a prayer and a protest. Curtis opened a new world for soul music—and, to borrow Mayfield’s own words, we’re still moving on up.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)