Milestones: Dirty Mind by Prince

On Dirty Mind, Prince discovered the formula that would define his genius: complete artistic freedom, embrace controversy, and an uncanny ability to inject pop hooks into the most taboo of topics.

Prince walked away from studio sheen and into a rented basement with a 16‑track, choosing heat over gloss. Alone in a Minneapolis house, he built songs that began as demos, played almost everything himself, and stepped into a new skin—trench coat, briefs, the “Rude Boy” pin—an image that made the music’s bluntness legible. The band orbit was tightening—Lisa Coleman newly in, Dr. Fink feeding a hook that would anchor the title track—yet control stayed in his hands. The industry expected continuity; what he delivered felt riskier and truer, the first time the record sounded like him.

Sound first, scandal second. The mix is dry and close—little reverb, lots of breath—so every clap and synth line lands without cushion. The 16-track setup leaves edges exposed: clipped drum patterns, single-line bass synths, and rhythm guitar shaved to a wire. The title song sketches the method in miniature: a two‑note keyboard figure born from Fink’s riff, a stubborn pulse, just enough harmony to imply a chorus. “When You Were Mine” brightens into power‑pop; “Uptown” opens the floor and names the freedom the record chases. Nothing hides behind polish. The minimal frame keeps the focus on voice, desire, motion.

One of the most gleefully scandalous moments on Dirty Mind arrives during the slow, synth-laced grind of “Head.” In this slightly downshifted funk groove, Prince spins a darkly comic tale of seduction and power. The scenario is archetypal Prince: a chance encounter with a bride on her way to church, portrayed with deadpan detachment by keyboardist Lisa Coleman. With dry, knowing humor, Prince’s narrator offers the blushing virgin a taste of forbidden pleasure—and she obliges, giving him exactly what the song’s title promises. In a tongue-in-cheek flourish, the escapade even leaves a stain on the bride’s wedding gown, a detail so outrageous it retrospectively evokes a presidential scandal decades later. This shocks her out of her vows, and she abandons the altar to “marry” the libidinous trickster instead. Prince seals the sordid deal with a sly vow of his own—promising to “love you till you’re dead.” It’s a macabre twist on ‘til death do us part, delivered with a mischievous grin.

On the surface, “Head” is pure erotic farce, set to one of Prince’s thorniest, most authoritative early grooves. Its bass synths churn and its drums snap with stripped-down confidence, exemplifying the album’s home-cooked, unvarnished sound. Yet beneath the kinky humor lies a subversive current of power play and youthful rebellion. Prince revels in flipping convention—corrupting a virgin bride and hijacking the sanctity of matrimony—all through the liberating force of funk. In 1980, this felt simply like an outrageous good time. But within a couple of years, as the shadow of AIDS crept over the sexual revolution, “Head” took on an eerily prescient resonance. Hearing Prince giddily promise to love someone “till you’re dead” in a song about carefree, casual sex became a darker joke in hindsight, one that Dirty Mind’s original listeners couldn’t have foreseen. The track’s gleeful exchange of wedding bells for hedonistic thrills now seemed to wink at danger, lending a morbid double edge to its comic depravity. Prince wasn’t making a grand statement about mortality in 1980—he was too busy having fun scandalizing prudes—but “Head” endures not just as dirty funk escapism, but as a time capsule of pre-AIDS audacity whose punchlines grew sharper with history.

The 93-second punkabilly blast “Sister” went even further, shredding the envelope entirely. In under two minutes, Prince dives headlong into rock’s most forbidden subject—incest—with a cheeky, adrenaline-fueled fervor. Over a Ramones-like guitar attack, he delivers Dirty Mind’s most jaw-dropping lyrics: “Incest is everything it’s said to be,” Prince yelps, as a teenage boy awakened to forbidden thrills by his older sister. The song barrels forward with ever-shifting meter and raw garage-rock energy, the band racing through start-stop riffs and breakneck drum fills as if to heighten the narrator’s manic confusion. There’s a nervy humor in the performance—its rockabilly rhythm careens and stumbles, and then, just as it builds to a frenzy, “Sister” cuts off abruptly, ending on a clattering cymbal crash without so much as a goodbye. The sudden stop leaves the transgression hanging in mid-air, unresolved. It’s as if even Prince, restless and uncontainable, couldn’t dwell on this taboo fantasy for more than a minute and a half before dashing off to the next idea.

What are we to make of “Sister”’s celebration of incest? At the time, some assumed Prince was simply seeing how far he could push dirty for dirty’s sake—a dare to his audience to either cringe or laugh along. Prince himself played coy about it. In a 1980 interview, when asked about his fascination with sexual taboos, he explained that sex was just “part of life… inside of all of us to some degree.” But he stopped short of clarifying whose life the twisted tale of “Sister” reflected. A few years later, pressed on whether the song was autobiographical or just shock value, Prince insisted with a straight face that “‘Sister’ is serious… All the stuff on the record is true experiences and things that have occurred around me… I wasn’t laughing when I did it.” It was a classic Prince move—doubling down on the song’s sincerity in one breath, then enveloping himself in mystery the next. Was he deadpanning for effect, or revealing a buried truth? The uncertainty only adds to the song’s transgressive power.

Dirty Mind’s provocations weren’t limited to sex. Prince saved one of his boldest statements for politics—sneaking it in at the very end, wrapped in the deceptively fun groove of “Partyup.” At first blush, “Partyup” feels like an invitation to party: a loose-limbed funk jam driven by a muscular bottom-end bass line and chattering guitar that nods toward rock and roll. Prince chants the title like a mantra—“party up, got to party up!”—over handclaps and a swaying rhythm that could get any club moving. But listen closer, and you realize this is dance music as protest. In the lyrics, Prince takes aim at the specter of war and the draft, issuing a youthful call to action that channels the late ‘60s spirit of rebellion. It was 1980, and President Jimmy Carter had recently reinstated draft registration for young men in the wake of global tensions.

Prince, at 22, was slightly beyond the draft’s grasp, but he gave voice to the generation just behind him—the teenagers who suddenly had to sign up for a possible war they wanted no part of. “How you gonna make me kill somebody I don’t even know?” he asks plaintively in the song’s bridge, cutting through the funk with a stark question that would have resonated strongly only five years after Vietnam. In that single line, his usually silky voice sounds incredulous and vulnerable, as if genuinely distressed by the notion of being forced to fight strangers. Then comes Prince’s answer to this coercive violence: a simple, defiant refusal. “You’re gonna have to fight your own damn war, ’cause we don’t wanna fight no more,” he shouts in the song’s climax. The band turns that line into a chant—a joyous, fist-pumping refrain that echoes the protest anthems of the previous generation. It’s a striking tonal shift on an album otherwise preoccupied with bedroom drama.

Dirty Mind is a homemade punk manifesto masquerading as a demo tape. In fact, the record was largely a demo—recorded by Prince in a rented Minneapolis house with just a 16-track studio, far from the polished halls of any Los Angeles facility. That D.I.Y. approach gives the album its unique feel: you can sense the minimalism in the music’s skeletal arrangements and the immediacy of ideas caught fresh to tape. Synth lines are buzzy and unadorned, drum machines (and drummer Bobby Z’s live kit) kick with simple, metronomic force, and the rhythm guitar is tight and unembellished. Prince stripped the songs to their barest essentials, banishing any excess fluff. Prince drew as much inspiration from the jagged edge of the burgeoning new-wave scene as from the smooth groove of the R&B world he came from.

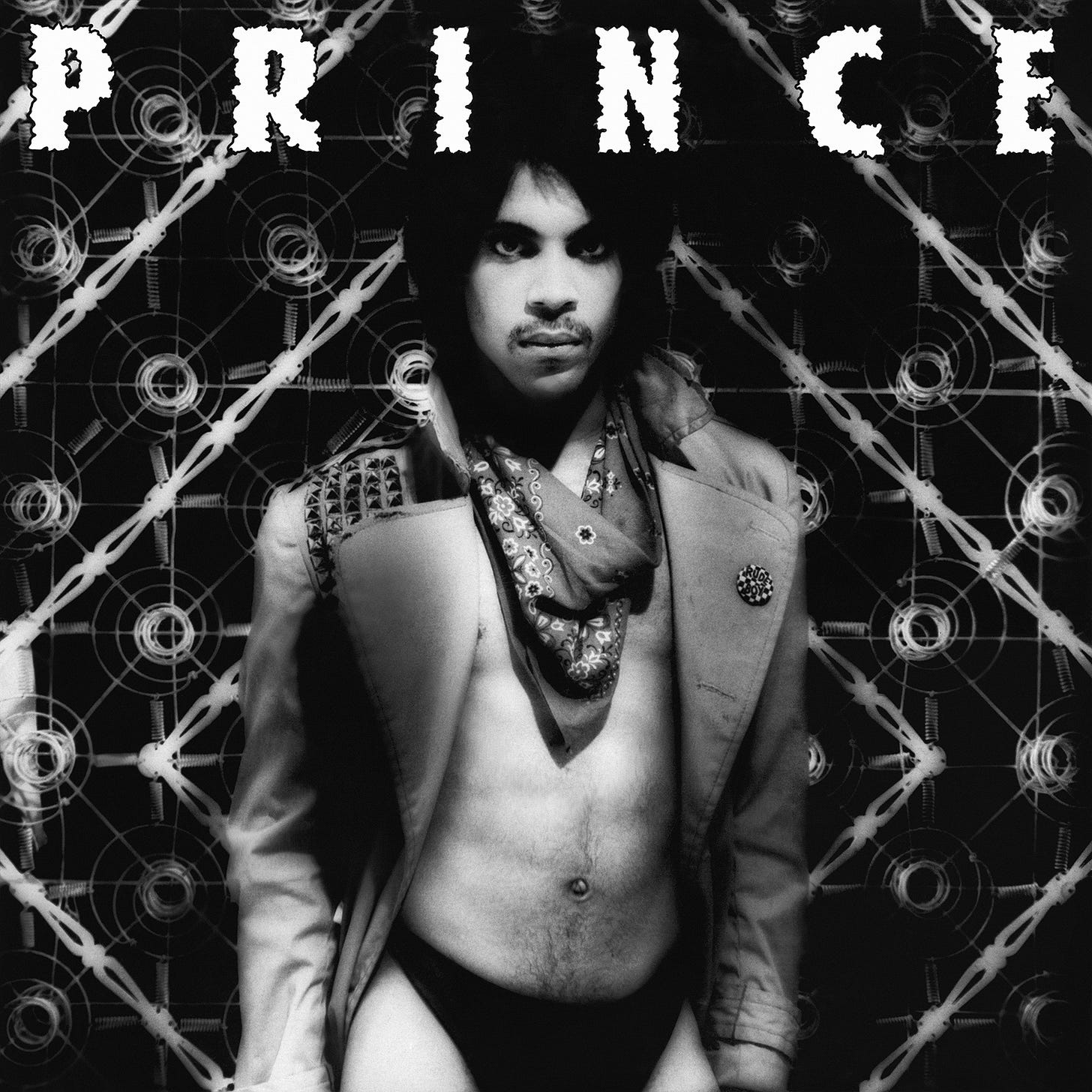

He rejects every label—is this R&B? Rock? Disco?—and by extension, rejects every authority that would tell him what a Black artist should or shouldn’t do. In 1980, with disco’s star fading and musical genres stratifying on segregated radio, Dirty Mind declared that funk and rock could be the same party, and that no subject was off-limits in a pop song. Prince’s attitude was pure punk in the broadest sense: not the three-chord sound, but the defiant DIY ethos and “screw you if you don’t get it” confidence. He wore a “Rude Boy” button on his coat on the album cover—a nod to the 2 Tone ska movement’s punk-mod slang—and stood there in black bikini briefs, stockings, and a trench coat, staring boldly at the camera. The image was confrontational, androgynous, erotic, and humorous all at once. It told the world everything it needed to know about the music inside: this was a record that invited you in with a come-hither smirk, even as it flipped off all convention.

Such an audacious album met with bemusement from the powers that be. When Prince delivered Dirty Mind to Warner Bros., some executives were reportedly shocked—and who could blame them? Here was their 20-year-old prodigy, the one they’d marketed as a polite R&B wunderkind, now singing gleefully about oral sex, threesomes, and incest over lo-fi funk-rock. There were murmurs at the label that maybe he should tone it down a notch. But Prince was adamant, and to their credit, Warner Bros. didn’t stand in his way. “They didn’t ask me to go back and change anything, and I’m real grateful,” Prince reflected later. “I wasn’t being deliberately provocative. I was being deliberately me.” That act of faith on the label’s part was rewarded artistically, if not immediately commercially. Upon release in October 1980, Dirty Mind barely cracked the Top 50 of the Billboard album chart. Radio was never going to touch songs like “Head” or “Sister,” and the album’s genre-blurring sound made it a tough sell to any single market. Black radio programmers balked at the screaming guitars, rock stations were wary of the funky grooves, and mainstream pop likely found the whole thing too risqué. But critical ears were listening, and they liked what they heard. In the influential Village Voice Pazz & Jop critics’ poll, it was ranked among the year’s best albums, an almost unheard-of honor for a raw R&B record by a virtually unknown Black artist.

Though its sales were modest, Dirty Mind quietly catalyzed a movement. The album became a touchstone for a new cohort of genre-bending artists and adventurous fans in the early ‘80s. In the clubs of New York and London, one could hear Dirty Mind tracks spinning alongside new wave and post-disco cuts—the common denominator being an anything-goes creative spirit. Uptown kids who loved rock and funk in equal measure found in Prince a hero who didn’t see those styles as opposed at all. He cultivated devotees across the spectrum: punks and new-wavers drawn to the album’s raw edge and anti-establishment flair, funk aficionados delighted by its stripped-down groove, even pop listeners catching wind of this enigmatic Minneapolis kid unafraid to be utterly himself. Dirty Mind’s influence could be felt in the work of contemporaries who, like Prince, blurred boundaries and shocked the status quo. Artists like Grace Jones, who that year reinvented herself as a new-wave funk queen, occupied a similar cultural space—fearless, androgynous, melding rock attitude with dance-floor rhythm.

The burgeoning downtown club scene that would soon launch Madonna was already taking notes from Prince’s playbook of sexual frankness and genre fusion. Even rock icons like The Clash found common ground with Prince’s rebel funk: the Clash’s genre-melding Sandinista! came out weeks after Dirty Mind, and one imagines that their open-eared fans could appreciate Prince’s punk-funk hybrid as simply another form of musical insurrection. By bridging racial and musical divides, Dirty Mind earned Prince a cult following that transcended the usual demographics. If you were into daring, ahead-of-its-time music in 1980—whether your taste ran to Talking Heads or Funkadelic, new romantic synth-pop or underground disco—chances are Dirty Mind was on your turntable, blowing your mind. In the years that followed, one could hear its aftershocks everywhere. The Minneapolis sound that Prince pioneered—that electro-funk minimalism laced with rock attitude—became the template for countless ’80s acts. From the Time and Vanity 6 to mainstream rivals like Michael Jackson, who toughened up Thriller with guitar swagger, the pop landscape began to reflect Prince’s liberated vision. And as the decade progressed, genre lines in pop music continued to blur—a trend Dirty Mind helped kick off. By the mid-‘80s, radio and MTV were embracing Black artists who rocked and white artists who grooved, fulfilling Dirty Mind’s quiet prophecy of a more eclectic pop future.

For Prince himself, Dirty Mind was the big bang that set his universe expanding. This audacious record reshaped the trajectory of his career, marking the moment Prince became Prince—the iconoclast, the boundary-pusher, the master of mixing high and low. In its wake came 1981’s Controversy, where he further politicized his funk; then 1999, which took the electro-rock experiments to the mainstream; and of course Purple Rain, the blockbuster that wouldn’t have been possible without the creative groundwork Dirty Mind laid. On Dirty Mind, Prince discovered the formula that would define his genius: complete artistic freedom, a fearless embrace of controversy, and an uncanny ability to inject pop hooks into the most taboo of topics.

The album’s fingerprints are on every genre Prince touched thereafter, and its spirit—bold, unapologetically freaky, and utterly danceable—left a lasting impact on the music of the 1980s. You can hear Dirty Mind’s DNA in the rock-funk amalgams that came after (from Van Halen playing with synths to INXS injecting funk into rock), in the evolution of R&B (as artists embraced more risqué themes and electronic beats), and in the very idea of the pop star as provocateur (Madonna’s shock tactics, Michael’s genre-hopping, even the androgyny of later icons like Grace Jones or admirers like Lenny Kravitz). By obliterating boundaries, Dirty Mind lit the fuse for a decade of innovation in rock, soul, pop, and dance music. It remains a manifesto of liberation that sounds as fresh—and as delightfully scandalous—today as it did in 1980. Prince’s dirty little album, recorded in a basement and too bold for radio, ultimately changed the rules for everyone. And in doing so, it ensured that the Purple One’s imprint on the ’80s would be not just meteoric, but revolutionary.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)