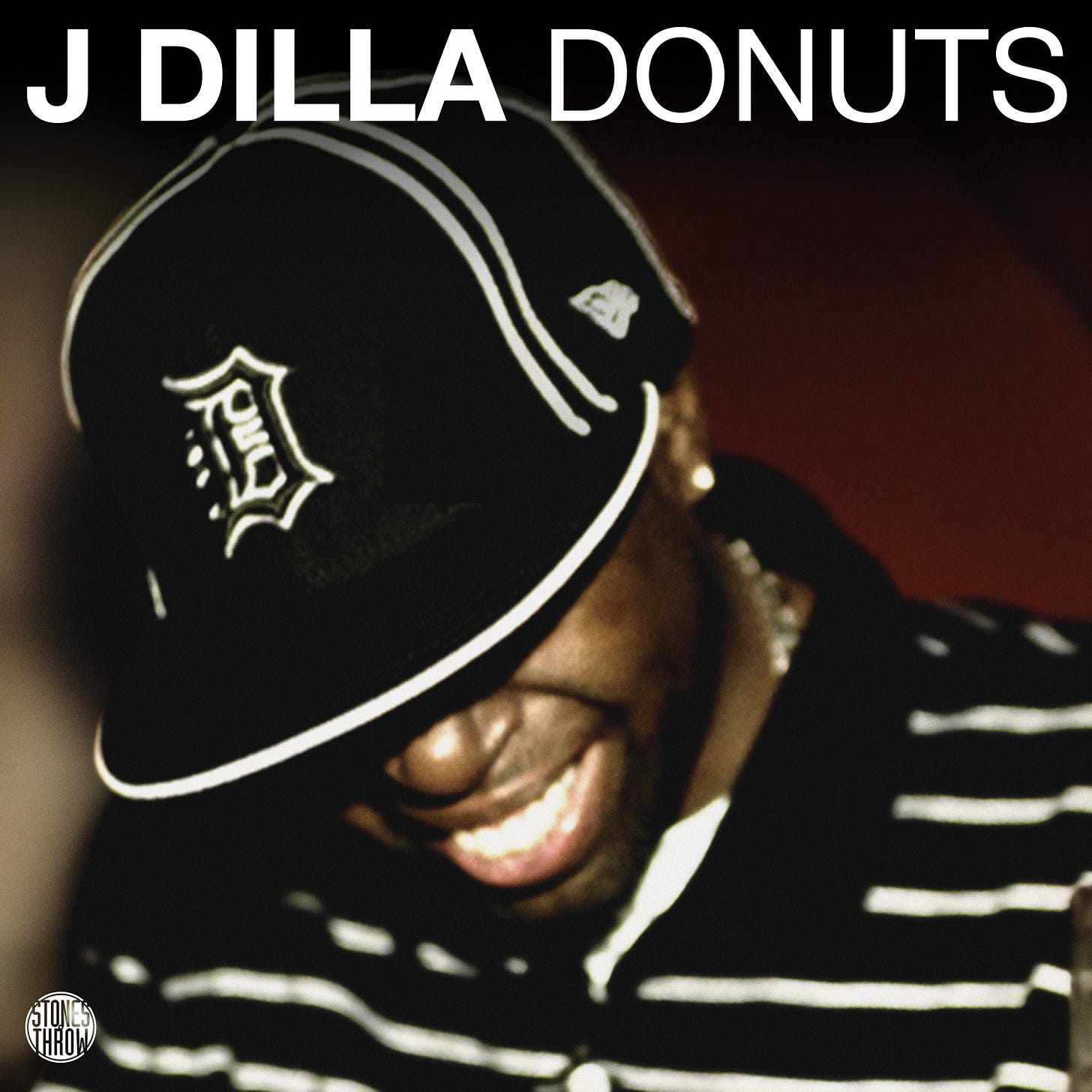

Milestones: Donuts by J Dilla

Dilla built this from a hospital bed with a sampler and whatever 45s friends could smuggle in. Thirty-one beats, most under two minutes, none wasted.

Detroit bred producers different. Not flashier or hungrier than New York or Los Angeles, just weirder in the best possible way. The city that gave hip-hop Amp Fiddler and the whole Conant Gardens crew seemed to specialize in cats who heard drums differently, who couldn’t quite land on the one the way everybody else did and didn’t want to. James Dewitt Yancey came up in that tradition, chopping samples for Slum Village before most underground heads knew Baatin’s name, flipping drums on “Runnin’” and “Players” for Pharcyde when backpackers were still trying to figure out if his off-kilter timing was intentional. You could trace his fingerprints through A Tribe Called Quest’s final run, across Common’s Like Water for Chocolate, deep into D’Angelo’s Voodoo. He had a decade of production credits stacked before anybody called him J Dilla on wax.

Donuts dropped three days before Yancey died, his body finally giving out after months of battling TTP and lupus, in and out of Cedars-Sinai while friends smuggled in 45s and he built beats on a Boss SP-303 from his hospital bed. No verses. No hooks in the traditional sense. Most of these joints don’t even crack the two-minute mark. The sequencing plays a trick too. “Outro” opens the album and “Intro” closes it, so the whole thing circles back on itself if you let it ride. Try to explain that to somebody who thinks instrumental hip-hop means DJ Shadow or trip-hop coffee shop music and watch their face.

The sampling on this thing stays ridiculous. Yancey pulled from everywhere. “Time: The Donut of the Heart” slows the Jackson 5’s “All I Do Is Think of You” down to a crawl, pitching Michael’s falsetto into something ghostly while drums knock underneath like a heartbeat that can’t quite stabilize. “Don’t Cry” takes the Escorts’ “I Can’t Stand (To See You Cry)” and slices it into eighth-note stutters, piano phrases dropping in and cutting out before you can grab them. “Workinonit” chops Mantronix and 10cc into siren-laced guitar loops that feel like a panic attack with a head nod.

What Dilla did with rhythm on these tracks is hard to describe without getting into music school talk, but here’s the simple version. His drums don’t sit on a grid. They lean, they drag, they rush in weird places. Quantize these joints and they’d fall apart. The kick might hit a hair late while the snare creeps early, and somehow your head still bobs because the feel is right even when the math says it shouldn’t work. MPC heads have been trying to reverse-engineer this swing for twenty years now. Good luck.

Most beat tapes let their instrumentals breathe. Dilla gave you half a minute and then yanked it away. “Glazed” barely finishes introducing itself. “Airworks” disappears faster than you can recognize what he sampled. You hardly get comfortable before the sample flips or cuts entirely and something new drops in. It sounds scattered on paper, but playing through it front to back the brevity starts making sense. Each joint is a complete thought, nothing wasted, no filler passages padding things out while you wait for a verse that’s never coming.

Everybody wants to pin the emotional weight here on death. The man was sick, yeah. He was building these instrumentals in a hospital room with limited equipment and limited energy. But “Bye” flips the Isley Brothers with this tender melancholy that would hit the same way whether the producer lived another fifty years or not. “Stop” interpolates Dionne Warwick asking “do you know the way” and it sounds like somebody driving through an unfamiliar city at 4 AM, exhausted, not sure where home is anymore. “Last Donut of the Night” brings Motherlode’s “When I Die” into something warm and fading, like remembering a party that ended hours ago while you’re still sitting in the parking lot.

This record caught critics off guard when it dropped. Underground heads knew Dilla’s work but mainstream outlets were still sleeping. Since then the accolades stacked up. Metacritic gave it their universal acclaim tag. Pitchfork ranked it 38th on their 2006 list and 66th for the whole decade. Rolling Stone eventually put it at 386 on their all-time list, which for a wordless beat tape released on an indie label is wild.

The influence spread sideways rather than down. Madlib already understood what Dilla was doing. Knxwledge built half his career on that same template while Kaytranada filtered the swing through house music. Flying Lotus took the fragmentation further into abstraction. Producers who never cite Dilla directly still end up reaching for that same loose-limbed drum feel because it became part of hip-hop’s language and stayed there.

Can you separate Donuts from the story around it? Probably not. The fact that these were a dying man’s final transmissions gives the whole thing extra gravity whether you want it to or not. But the record holds up on its own terms because it has ideas. The circular structure, the refusal to let instrumentals outstay their welcome, the deliberate imperfection in the drum programming. These are choices a healthy artist could make and some sick artists never would. Yancey made them while hooked up to machines, working with whatever records his people could carry through hospital security.

Thirty-one donuts, each one gone before you finish tasting it. When you realize “Welcome to the Show” rolls back to “Donuts (Outro),” you figure out the whole thing was designed to never really end. Whether that’s a statement about mortality or just a producer’s joke about his dessert-themed title, who knows. Maybe both. The wheel keeps spinning regardless.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)