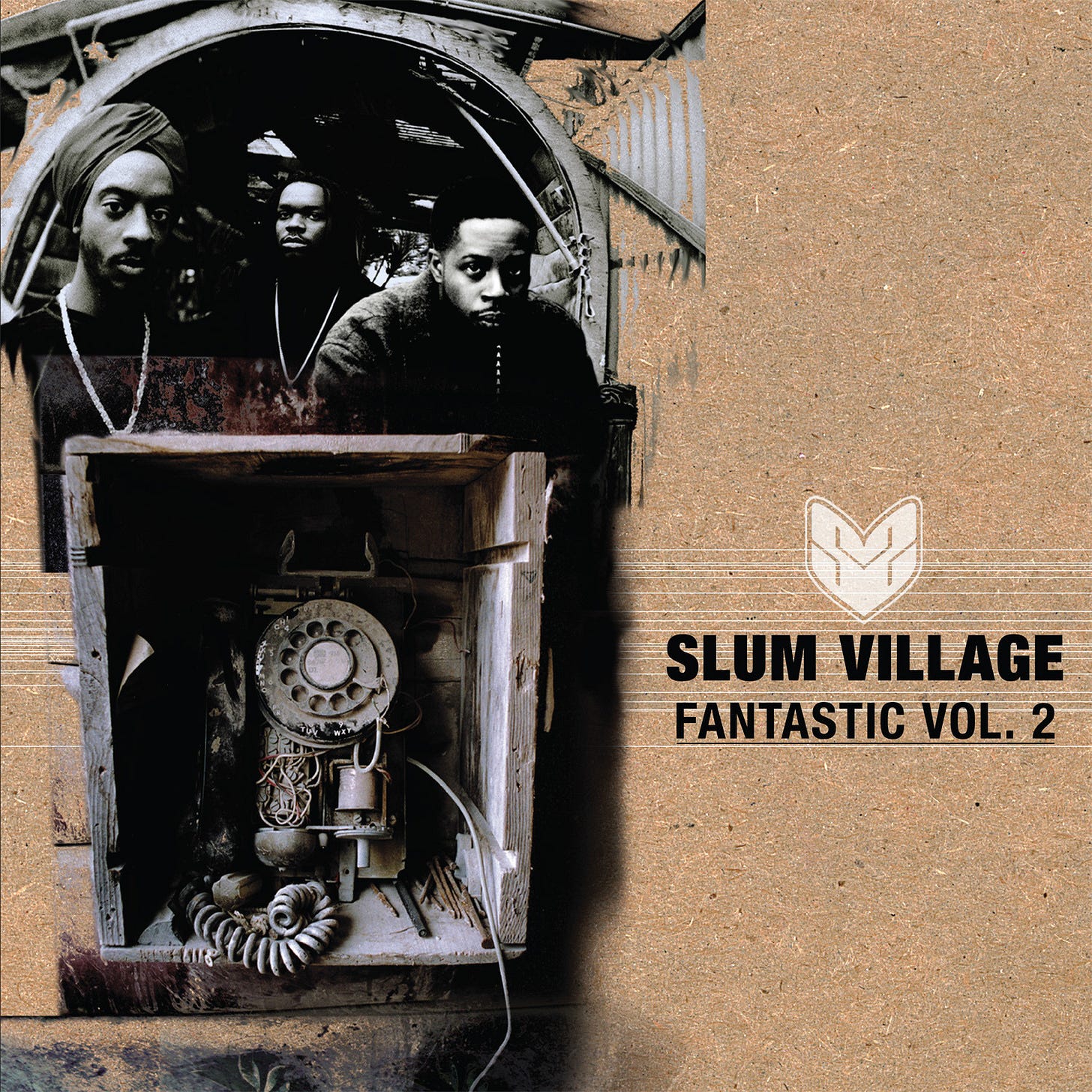

Milestones: Fantastic, Vol. 2 by Slum Village

Fantastic, Vol. 2 has lived a double life, passing from hand to hand as a beloved underground tape, while simultaneously serving as a touchstone whose influence reaches far beyond Detroit.

Twenty-five years have gone by. Wow. For three and a half decades, Fantastic, Vol. 2 has lived a double life, passing from hand to hand as a beloved underground tape, while simultaneously serving as a touchstone whose influence reaches far beyond Detroit. What first sounded like a relaxed conversation among three friends—James “J Dilla” Yancey, Titus “Baatin” Glover, and R. L. “T3” Altman—has proven to be a field manual for the way modern hip‑hop, neo‑soul, and even forward‑leaning jazz feel the beat. Listeners still study its swing, quote its harmonies, and borrow its easy confidence when they push their own music past the grid. The album’s warmth sits close to the ear, but its influence stretches wide enough that some devotees, only half‑joking, call it the second classic hip‑hop record of our millennium.

The project almost didn’t reach the record racks that first embraced it. A major‑label (A&M Records) shake‑up shelved the finished master for years while reference copies leaked onto cassettes, then onto early file‑sharing hubs. Rough mixes circulated so heavily that newcomers often thought the bootleg was the official edition; the group’s core audience had memorized track lists long before any stock reached stores. That pre-release life hardened the album’s mythology, making it feel like contraband, a whispered secret from the Motor City that traveled farther every month. When the sanctioned version finally appeared, many long‑time tape holders bought it anyway, treating the polished sequencing as proof that their private obsession was now part of the public record.

Detroit has a history of transforming local rhythms into a global language—Motown’s pocket, Parliament’s cosmic funk, techno’s machine pulse, and Fantastic, Vol. 2 fits that lineage by grounding future-minded ideas in neighborhood detail. “Conant Gardens” opens with a roll call of blocks and corner stores, declaring that the group’s soft‑spoken style belongs to the same east‑side streets that shaped it. Tape hiss and laughter blur into the mix, suggesting a basement rehearsal more than a corporate studio. That sense of place carries through the record: even when Q‑Tip, D’Angelo, or Common drop by, the pacing still feels like Detroit—unhurried, curious, comfortable, leaving space between the snare and the next thought.

Much of that space exists because Dilla decided drums could talk by leaning just behind the beat. He tapped pads on his MPC rather than relying on preset quantize grids, letting kicks arrive a hair late and hi‑hats rush a shade early. The pattern sounds casual but lands with geometric precision, coaxing MCs to relax their cadences and singers to slide into half‑voice harmonies. Engineers who later dissected the sessions have confirmed that almost nothing lines up with the digital ruler, yet everything feels locked. That gently lopsided swing, sometimes called “drunk” time, became the session template for hip‑hop rhythm sections in the decades since.

Before Dilla applied those ideas to this album, he had worked on them in two overlapping collectives: the Ummah (with Q‑Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad) and the Soulquarians (with Questlove, D’Angelo, and others). Those circles sharpened his taste for light percussion, Fender Rhodes chords, and roomy low‑end. In Slum Village, he refined the equation further, removing ornamental layers until only essential timbres remained. The result is a mix that breathes: snares never crowd a verse, bass lines murmur rather than bully, and the tiniest vocal ad‑lib floats in three‑dimensional relief. That restraint turned out to be a road map for Voodoo, Mama’s Gun, and a host of early‑century R&B projects that prized head‑nod feel over polished sheen.

“Get Dis Money” loops a ghostly Rhodes figure until it becomes hypnotic, then lets T3 and Baatin trade measured bars about financial aspiration with none of the chest‑beating common to the era; even the boasts ride the pocket instead of trying to escape it. “Raise It Up” shifts gears by pitching a keyboard stab so high it almost splinters, daring the trio to double their flow without losing clarity. “Untitled/Fantastic” glides at half‑tempo, its handclaps cushioned by sub‑bass thumps as the rappers meditate on everyday stresses. “Climax” pairs whispered come‑ons with a flute‑like synth, turning intimacy into groove rather than slow‑jam cliché. Each beat illustrates a different aspect of Dilla’s palette with chopped chords, filter‑warmth, negative‑space percussion—yet all share the same roomy atmosphere.

Songs built around love, romantic and communal, anchor the album. “Tell Me,” produced in tandem with D’Angelo, is almost austere: a brushed rimshot, a few organ swells, and hushed call‑and‑response hooks. That minimalism matches lyrics that sift through doubt without leaning on melodrama. “Fall in Love” answers with tenderness of a different sort, its looped vibraphone tides framing a soft-spoken warning that clings too tightly to art or romance, and both will vanish. The writing sidesteps sentimentality; instead, the group treats affection as craft, something to polish until it shines just enough.

Hometown pride surfaces in “Players,” where Dilla flips a choral sample until it seems to pronounce the song’s title, an auditory illusion that still prompts producer forums to trade theories. The word‑play sample rides shimmering high notes while the low end thumps like an AMC 808 on Detroit pavement. T3 and Baatin salute neighborhood survivors, toggling between introspection and swagger without changing tempo. The technique of repurposing an unrelated vocal so that it sounds like a new phrase that has become a production parlor trick, but few successors match the subtlety of the original flip.

Q‑Tip drops a compact handoff on “Hold Tight,” declaring that the lineage he built with A Tribe Called Quest now continues in Detroit. Busta Rhymes interrupts “What’s It All About” with elastic internal rhymes, yet Dilla’s muted drums absorb the energy instead of letting it topple the groove. Pete Rock co‑produces “Once Upon a Time,” trading trademark horn stabs for low‑pass murmur to match the album’s texture. Common weaves through “Thelonius,” weaving pocket talk around swung ride cymbals that could have come from a late‑night jazz combo. The cameos feel less like an outside booking than a family reunion, proof that the LP’s central idea (a roomy, head‑nod canvas) could welcome any voice that respected the pocket.

The trio keeps stakes human‑scale. They toy with flirtation, muse on city politics, outline hopes for stable income, and marvel at the act of creating itself. Baatin’s phrasing zigzags between syllables, sounding like free verse until you catch the internal rhymes. T3 balances that looseness with direct statements about craft: rhyme schemes, studio hours, vinyl hunts. Dilla, often overlooked as an MC, delivers understated lines that mirror his drum work, slightly behind the downbeat but never sleepy. Together, they present Detroit not as a casualty of de‑industrialization but as a generator of ideas, where understated style counts for more than bravado.

Those ideas traveled far. Questlove has credited Fantastic, Vol. 2 with sparking the neo‑soul spirit—live musicians adapting hip‑hop timing, long before large audiences had names for the movement. Robert Glasper later explained that the project changed how pianists place chords, encouraging them to hover behind the beat rather than chase it head‑on. Black Milk describes the album as necessary study material for anyone raised in Detroit’s beat scene, arguing that without it, the city’s next wave of producers would have aimed their drums in totally different directions. Such testimonials illustrate how the record reshaped not only rap production but real‑time musicianship across genres.

The album continues to guide creators who were children, or not yet born, when bootlegs first hit the streets. Jazz groups improvise over “2U4U” during soundchecks; lo‑fi beat‑makers reassemble “Fall in Love” chord progressions for streaming playlists; gospel choirs sample “Untitled/Fantastic” for Sunday‑morning warm‑ups. Engineers cite Dilla’s subdued high‑hat EQ as a textbook example of how to leave room for melodic textures. Even hardware design owes a debt, as several modern drum machines ship with swing algorithms modeled after the album’s idiosyncratic pulse, enshrining what began as a human feel in silicon.

Inside Detroit, the record stands alongside Motown’s tight grooves and techno’s metallic thump as proof that the city turns constraints into signatures. Limited studio budgets forced the group to rely on borrowed microphones and thrift‑store vinyl; those very constraints encouraged the sparse layering that became their hallmark. The result honors earlier Motor City economies of sound: Berry Gordy’s assembly‑line minimalism, the MC5’s stripped‑down power, even Juan Atkins’ skeletal drum patterns. Fantastic, Vol. 2 doesn’t imitate those precedents—it calmly joins their conversation, confirming that Detroit’s musical heritage prizes pocket, innovation, and self‑determination in equal measure.

No single element explains why the record still feels current after thirty‑five years. Some point to Dilla’s headphones-crafted rhythms, others to the conversational flow that sidesteps forced hooks, and still others to the way guest spots serve the song instead of catering to marketing schedules. Yet the most durable quality may be balance. Every component—bass line, kick drum, vocal aside—knows when to step forward and when to fade, the way seasoned neighbors trade stories on a porch: animated, but never shouting over one another. That poise allowed the album to slip quietly into the culture and, from that unassuming perch, redraw the rules of groove‑based music.

As anniversary tributes pile up, it remains tempting to treat Fantastic, Vol. 2, as a sacred relic. The better approach is to continue using it in everyday settings (such as car rides, jam sessions, and late-night study halls), as it was designed for everyday use. The album teaches by trusting silence, respecting the swing, honoring your hometown’s accent, and remembering that innovation can sound effortless when the tempo feels human. Those lessons continue to echo in everything from sold‑out jazz halls to bedroom rap demos, ensuring that this Detroit masterpiece retains the casual authority that made it a blueprint in the first place—still Fantastic, forever in the present tense.

Great (★★★★☆)