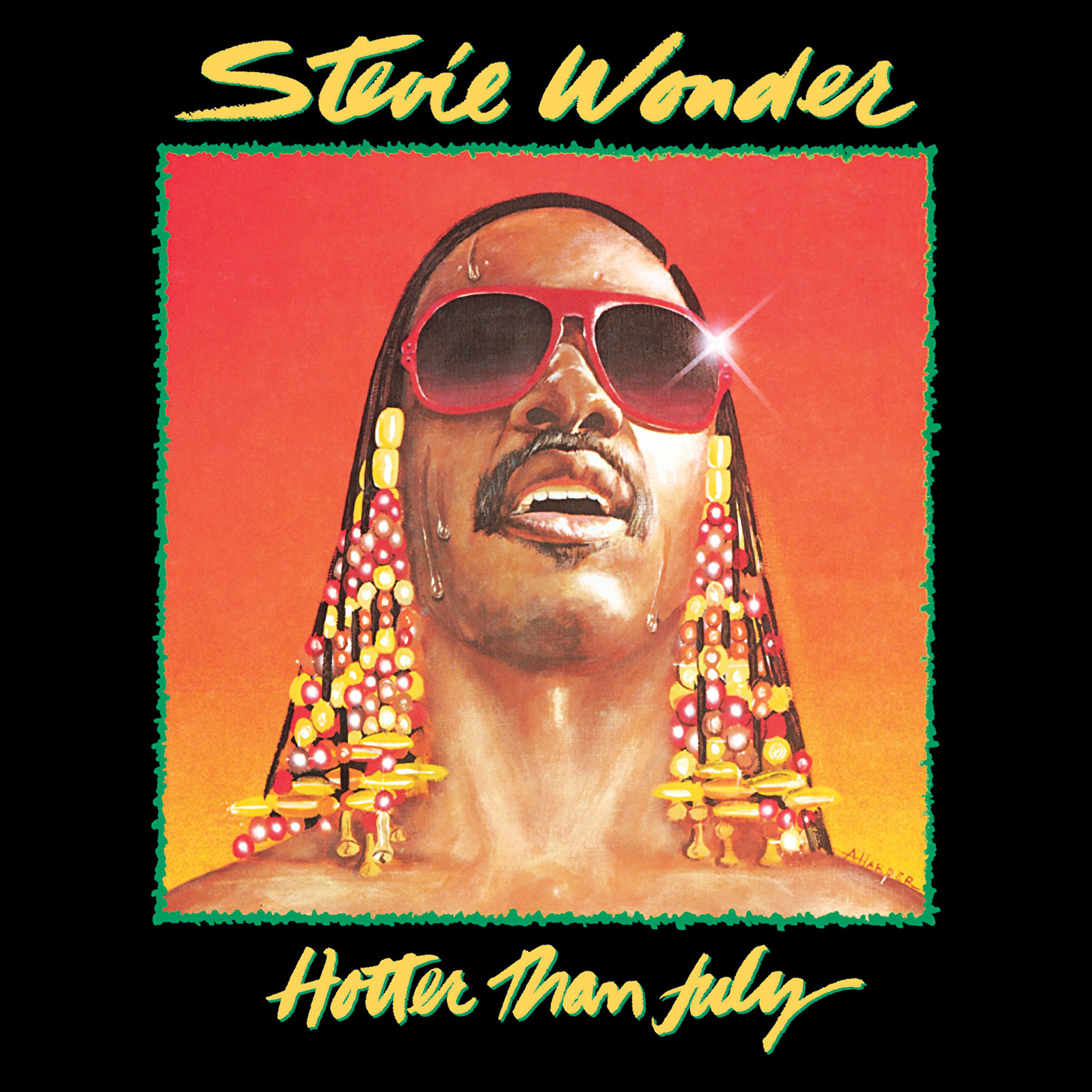

Milestones: Hotter Than July by Stevie Wonder

Stevie Wonder delivered an album that may not have been hotter than every July that came before, but certainly one that still burns bright in the pantheon of Black music excellence.

Four years had elapsed since Stevie Wonder’s creative zenith with Songs in the Key of Life (1976), a period during which popular music tastes had shifted under the glitter of disco and the angular energy of new wave. By 1980, dancefloors pulsed with Donna Summer and the B-52’s, and many wondered how Wonder—after an unprecedented run of five landmark albums from 1972–1976—would navigate these trends. Stevie had earned a respite after Songs in the Key of Life, stepping back as disco and new wave began to dominate the charts. Now the question loomed: would he adapt to the zeitgeist or continue marching to the beat of his own drum (often literally, given his multi-instrumental genius)?

Hotter Than July delivered Stevie’s answer—a resounding reaffirmation of artistry over fads. Rather than hopping on prevailing sounds, Wonder doubled down on what he did best: rich songwriting, inventive arrangements, and hands-on production of the sort that made his 70s work timeless. He recorded most of the album at his newly acquired Wonderland Studios in Los Angeles, immersing himself in a state-of-the-art digital recording setup and playing many instruments himself, from drums and bass synth to his signature keyboards. The result was an album that felt current in polish yet true to Stevie’s soulful core. Fans greeted it warmly—it was widely seen as Wonder’s big return after the more perplexing experimental detour of Journey Through the Secret Life of Plants (1979). If Plants had left some unsure about Stevie’s direction amid a music landscape shaken by disco’s boom and bust, Hotter Than July quelled any doubts so resoundingly that they seemed foolish in hindsight.

From its first seconds, the album announces a joyous comeback. “Did I Hear You Say You Love Me,” the opener, kicks off with an exultant shout and a driving four-on-the-floor beat that proves Stevie could nod to disco’s energy without sacrificing his soul. It’s a brassy, uptempo funk number, built on Nathan Watts’s fat bass and a horn riff, yet even as it urges feet to move, Wonder’s melodic exuberance and gospel-tinged call-and-response keep it firmly grounded in R&B. The brightness of the production—Stevie’s 1980 recordings had a shinier, synth-embracing mix than the warm analog textures of his 70s LPs—gives the track (and much of the album) a contemporary sheen. But beneath the new gloss, Wonder’s craft in arrangement is evident: he layers vocals and instruments with the same meticulous ear that powered his classics, ensuring that even a danceable tune retains musical richness.

Where Hotter Than July is less grandiose than Wonder’s mid-70s epics, it’s also more compact and exuberant. After two double-albums in a row, Stevie pared this project to a tight 10 songs with nary a wasted note, as if aiming for maximum impact in a single LP. The record brims with musical detours and experiments that feel like celebratory victory laps rather than trend-chasing. Take the album’s standout single, “Master Blaster (Jammin’).” Stevie had become close friends with Bob Marley in the late 70s, even sharing stages with the reggae icon, and reggae’s influence had seeped into his creative sensibilities. “Master Blaster” is Wonder’s explosive reggae-inflected tribute to Marley—a slow-swaying ode that even name-checks Bob in the lyrics. Wonder uses Marley’s own 1977 jam, “Jamming,” as a loose musical template, building on its lilting guitar skank and percussion groove while layering on his expanded palette of keyboards and horns. The track merges an infectious rhythm and an uplifting message of musical unity, demonstrating Wonder’s knack for incorporating global influences into his sound while maintaining his artistic integrity. You can hear the pleasure in his delivery—his free-floating melody lines and upbeat fervor radiate the hope and celebratory vibe behind the song.

Another stylistic curveball arrives with “All I Do,” the album’s second track, which carries a subtle disco tinge in its smooth midtempo groove. But the song’s origins reach back far before Studio 54. In fact, “All I Do” was written by a teenage Stevie in 1966 in collaboration with Motown colleagues Clarence Paul and Morris Broadnax. Motown star Tammi Terrell recorded it that year, intending it as a follow-up to her duet hits with Marvin Gaye, but her version remained shelved in the vault for decades. Rather than let the tune languish in obscurity, Wonder revisited it for Hotter Than July, effectively giving new life to an old love song from his youth. He didn’t merely dust it off—he supercharged “All I Do” into a modern R&B gem. The 1980 rendition is exuberant and electric piano-fueled, propelled by a bouncing rhythm that’s equal parts late-60s Motown and contemporary post-disco soul. Stevie’s lead vocal is ardent and soulful, declaring devotion (“All I do is think about you”) with gospel-like intensity. And in a stroke of communal magic, he enlisted an all-star chorus of friends to back him: you can hear Michael Jackson’s youthful tenor among the backing vocals, joined by O’Jays legends Eddie Levert and Walter Williams, Betty Wright, and others harmonizing jubilantly. Their voices swoop in and out behind Stevie, accentuating the fervor of each refrain.

Throughout Hotter Than July, Wonder balances crowd-pleasing fun with substantive songwriting. His range of influences on this album is remarkably broad, yet it all coheres under his production. “I Ain’t Gonna Stand for It,” for instance, finds Stevie pulling off a surprisingly authentic country-soul vibe. Over a twangy guitar lick and a shuffling beat, Wonder adopts a drawling, down-home inflection—so convincing that some listeners didn’t recognize his voice at first. He even brought in Charlie and Ronnie Wilson of the Gap Band for backing vocals on this track, adding a touch of Oklahoma funk to the mix. The song’s country-funk flavor was so accessible that it later became a hit on the country charts in a cover by Baillie & the Boys in the late ’80s. Here in 1980, Stevie was effectively testing the boundaries of R&B by pulling from Nashville and Urban Cowboy-era pop-country stylings. Yet even as pedal steel guitar glides through the arrangement, Wonder’s own groove sensibility anchors the tune. It’s a breezy experiment—not as weighty as his social anthems, perhaps, but it shows Stevie’s musical curiosity was intact. And as always, he had a knack for melody; even delivered in a semi-twang, his chorus (“I ain’t gonna stand for it!”) burrows into your ears.

Hotter Than July covers the spectrum from matters of the heart to matters of conscience. Stevie was never one to shy away from social commentary (this is the troubadour who wrote “Living for the City” and “Village Ghetto Land”), and here he includes “Cash in Your Face,” a hard-funk protest of housing discrimination. Over a choppy synth bass and clavinet groove, he assumes the perspective of landlords who refuse to rent to a black man despite his qualifications—“We don’t want your kind living here,” they sneer, as Stevie dramatically illustrates racist redlining practices. The title itself is a clever play on words (cash-in-your-face as in paying upfront, and the literal slap in the face of prejudice). It’s a bristling track that harks back to the pointed social narratives of Innervisions, reminding listeners that Wonder’s conscience was as vigorous as his romantic spirit. The issue of housing inequality was timely, and Stevie channeled it into a song that grooves even as it educates.

On the opposite end of the emotional spectrum, Hotter Than July closes with two songs that together form a kind of encore, each striking a deep chord for different reasons. “Lately” is the penultimate track, and it remains one of Stevie Wonder’s most achingly intimate ballads. Stripped of the album’s funky trappings, “Lately” is just Stevie at the piano, accompanied by minimal rhythm—a stark arrangement that lets every quiver in his voice tell the story. And what a sorrowful story it is: the lyrics sketch a man tortured by suspicions of a lover’s infidelity, rendered in disarmingly direct lines. “Lately I have had the strangest feeling, with no vivid reason here to find,” he begins, setting a mood of anxious introspection. The melody is gentle and mournful, and as Wonder moves into the chorus, his voice soars into a higher register packed with vulnerability (hitting notes that would later challenge many a cover artist). It’s the kind of soul-baring ballad that transfixes an audience; you can picture a lone spotlight on Stevie at his keyboard, pouring out every ounce of hurt in his heart. Decades on, the song still resonates deeply—so much so that R&B vocal group Jodeci had a hit in the 1990s with their cover, bringing “Lately” to a new generation. Wonder’s original performance, however, remains unsurpassed in its remarkable honesty and ache.

On its surface, “Happy Birthday” functions as a joyous funk/pop anthem—built on a synth-heavy groove and a chorus so catchy and upbeat that it has been sung at countless birthday parties ever since. (Indeed, in Black communities especially, Stevie’s “Happy Birthday” has practically become the go-to rendition for festivities, often preferred over the traditional public domain tune.) But Wonder’s aim here was not simply to craft a party song. The song was dedicated to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Stevie wrote it as a rallying cry in his campaign to see King’s birthday made a U.S. national holiday. At the dawn of the 80s, that cause was still far from assured—MLK had been assassinated in 1968, yet over a decade later, there was still no federal holiday in his honor. Wonder decided to use music as a vehicle for change. In the album’s liner notes, he printed a plea for the holiday, alongside photos of King and civil rights struggles, urging fans to support the cause. “Happy Birthday” was the musical centerpiece of that effort. In the verses, Stevie pointedly wonders “how a man who died for good could not have a day that would be set aside for his recognition”—calling out the absurdity that the country had yet to officially commemorate Dr. King. That line, delivered with Stevie’s mix of indignation and optimism, cuts through the song’s jolly arrangement like a challenge to the nation’s conscience.

Upon the album’s release, he turned the momentum into action—organizing rallies, using his Hotter Than July tour to advocate for the holiday, and even marching in Washington. The impact was tangible. By November 1983, legislation for Martin Luther King Jr. Day was passed, and the first official holiday was observed in 1986. It’s widely acknowledged that Wonder’s relentless campaigning (with “Happy Birthday” as its anthem) played a key role in galvanizing public support. Thus, Hotter Than July’s final song isn’t just an exuberant album closer; it’s a milestone in Stevie’s legacy of social activism. Little wonder that the album’s inner sleeve was entirely devoted to the King tribute and call to action—this was music as history in the making.

Granted, Hotter Than July may not have the conceptual grandeur of Innervisions or the sprawling ambition of Songs in the Key of Life, but in many ways it didn’t need to—by 1980, Stevie wasn’t out to top himself for complexity, he was out to prove he could still connect in a new musical era. And connect he did. The album was a commercial smash (peaking at #3 in the US and #2 in the UK) and yielded multiple hit singles across genres. More importantly, it proved that Wonder’s artistry was alive and well as the 80s dawned. This record can be seen as both a worthy successor to the ‘72–‘76 classics and a transitional detour into the slicker pop landscape of the 1980s. On one hand, it’s Stevie doing what Stevie does best: concocting pop-soul masterpieces and heartfelt ballads with seemingly effortless magic – an album of seemingly endless abundance. On the other hand, its tighter song cycle and embrace of synths and digital recording hinted at the new directions Stevie would explore in the coming years, from the synth-funk of In Square Circle (1985) to collaborations with Paul McCartney and beyond. Hotter Than July occupies a special place as the capstone of Wonder’s classic era and the bridge to his commercial peak in the mid-80s. Some have called it his last truly great album; others simply view it as yet another proof of his enduring genius, a reminder that even when not reinventing the wheel, Stevie Wonder’s music in 1980 could uplift the spirit and stir the soul as strongly as ever.

The disco craze that raged when Hotter Than July was released has long since cooled, and new wave is now old school—but Hotter Than July still feels warm, alive, and meaningful. Its songs continue to be played at barbecues and family reunions (“Master Blaster” never fails to get people dancing), at weddings and karaoke nights (where brave singers tackle “Lately”’s high notes), and at every Martin Luther King Day celebration (where Stevie’s jubilant “Happy Birthday” is essentially an unofficial national anthem). By resisting short-lived trends and leaning into the timeless values of melody, passion, and social engagement, Stevie Wonder ensured that this album would age gracefully. Hotter Than July captures an artist at a crossroads who chose the path of authenticity—choosing to carry the flame of 70s soul into a new decade’s summer. In doing so, Stevie delivered an album that may not have been hotter than every July that came before, but certainly one that still burns bright in the pantheon of Black music excellence, a soulful midsummer triumph in the long arc of Wonder’s brilliance.

Standout (★★★★½)

There was a period where I played the vinyl everyday. This is one of my favorite works of his.