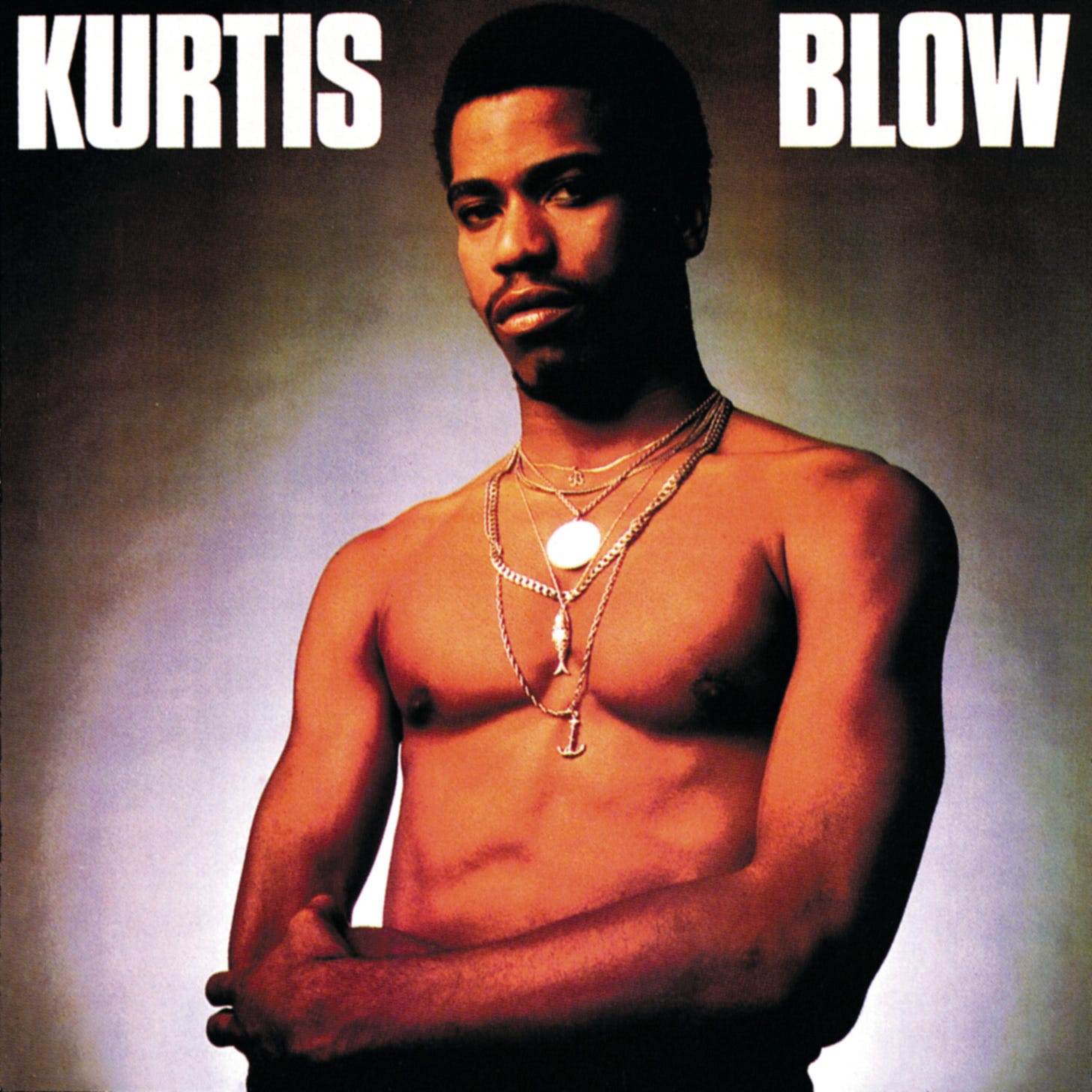

Milestones: Kurtis Blow (Self-Titled) by Kurtis Blow

By spinning Kurtis Blow’s self-titled debut LP, you get to witness hip-hop inventing the album format in real time. You hear the first footsteps of an art form learning to walk.

When hip-hop was still mainly a 12-inch singles game in 1980, the very idea of a rap LP was revolutionary. Most early MCs made their mark on wax one song at a time—think Sugarhill Gang’s lone hit or Grandmaster Flash’s early singles—and a full-length album was almost unheard of in rap’s formative years. Into this landscape stepped Kurtis Blow, a 20-year-old Harlem-bred rapper with a charismatic style and big dreams. His self-titled debut wasn’t just another record—it was one of hip-hop’s first albums ever, and notably the first rap album released on a major label (Mercury Records). In the context of the 1979–1980 era, known as the old school era, this was a pioneering move that helped take hip-hop from block parties to the national stage.

Kurtis Blow had already made history once: in late 1979, his infectious single “Christmas Rappin’” had sold hundreds of thousands of copies, making him the first rapper with a bona fide hit on a major label. Mercury, however, wasn’t ready to bankroll an album on the strength of a novelty holiday rap alone—they wanted proof that Blow was no one-hit wonder. That proof came in June 1980 with “The Breaks.” Over a funky, brass-and-drums groove spiced with handclaps and DJ scratches, Kurtis Blow crafted an ode to life’s ups and downs that doubled as a guaranteed party-starter. “The Breaks” became a smash: it shot to #4 on Billboard’s R&B chart and even cracked the pop Hot 100. More importantly, it earned the distinction of being the first-ever gold-certified rap single, selling over half a million copies. When Blow commands off the top, “Clap your hands everybody, if you’ve got what it takes,” it’s an invitation to celebrate the good and bad “breaks” in life. Over six minutes, he flips the word “break” through countless meanings—breaking up, catching a break, breakdancing—while the band vamps on an original funk riff (no samples here, just a tight live ensemble in the groove). The track’s call-and-response energy, with Blow’s booming voice leading the crowd, captures the feel of a late-’70s Bronx park jam pressed onto wax. “The Breaks” still stands as an iconic anthem; its lively a cappella intro and extended drum breakdown have been sampled and cited endlessly in hip-hop history. Hip-hop had been “in the moment” music—this album showed it could be bottled on vinyl, and “The Breaks” was the proof.

With “The Breaks” kicking open the door, Mercury Records greenlit Kurtis Blow the album, released in September 1980. In assembling the LP, Blow and his producers J.B. Moore and Robert “Rocky” Ford set out to showcase hip-hop’s versatility. Could a rap album hold a listener’s attention across multiple tracks, each with a different flavor? The result was a collection that plays almost like a portfolio of what early rap could be—from battle rhymes to party jams, from street reportage to genre-blending fusions. Kurtis himself later said that the first album served as the basis for the format of hip-hop, in terms of the different ideas and styles an artist could use. It was as if Blow and his team were testing the boundaries of the new genre, proving that rap was malleable, capable of taking the shape of funk, disco, rock, or even country-western sounds.

The album’s standout tracks remain its purest hip-hop moments. Besides “The Breaks,” the most famous is “Rappin’ Blow, Part Two.” As the opener on Side A, it immediately establishes a party atmosphere with a thumping bassline and lively horns. The title isn’t arbitrary: this track is literally the sequel to “Christmas Rappin’,” picking up where Blow’s breakthrough single left off. Back in ’79, “Christmas Rappin’” had been an audacious 8-minute jam that filled Side A of Kurtis’s debut 12-inch; it started with a holiday-themed rap and then, in its second half, shifted into an extended, non-seasonal rhyme routine. Rather than include the full song on the album, the decision was made to split it in two—giving listeners a “Part 2” that focuses on those party-rocking routines, stripped of the Christmas references. The album offers the payoff without the setup: “Rappin’ Blow, Part 2” is the back-end of “Christmas Rappin’” presented as its own track. It’s a funky, carefree brag rap in which Blow introduces himself and his mic skills to anyone who missed the single. Over a Chic-inspired groove—the same “Good Times”-esque feel that underpinned many early rap records—he flows in a confident, singsong cadence, throwing out smooth boasts and crowd chants. Yet what must first-time LP buyers in 1980 have thought upon discovering that the famous “Christmas Rappin’” was nowhere in full on the album? The label’s choice not to include the original track—arguably one of Kurtis’s signature songs—in its entirety left a gap. Mercury Records likely assumed a seasonal song might date the album or distract from Kurtis’s new material.

Side B’s “Hard Times” reveals another dimension—one that proved highly influential. Over a slower, bluesy-funk rhythm, Kurtis turns his attention to the reality of the streets: unemployment, inflation, hustling to survive. “Hard times spreading just like the flu/You know I caught it just like you,” he raps in the opening lines, striking a tone of empathy and warning. In 1980, this kind of social commentary in rap was almost unheard of; most MCs were still focused on boasting or rocking the crowd. Blow, however, delivered a kind of street economics lesson, describing desperation and determination in the same breath. “The prices goin’ up, the dollar’s down/You got me fallin’ to the ground,” he rhymes, capturing the economic angst of the early ’80s recession era. He even implores, “Watch out homeboy, don’t let it catch you,” as if trying to inoculate his community against the spreading hardship.

“Hard Times” was a precursor to what would become conscious rap’s breakthrough moment: Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five’s “The Message” in 1982. Kurtis Blow was addressing social issues a full two years before “The Message” hit the radio. A young group from Hollis, Queens—Run-D.M.C.—respected “Hard Times” enough to record their own version of it on their debut album in 1984, effectively making it one of hip-hop’s first cover songs. Comparing the two, one can hear how quickly the genre evolved: Blow’s original features a live band feel, upbeat guitar riffs, even cheerful shouts of “Get funky!” and “To the bridge!” mid-song, keeping it rooted in the party-rap tradition. Run-D.M.C.’s remake, with its stark synth stabs and hard beat, stripped away the disco sheen to amplify the grit of the message. Without Kurtis paving the way—proving that rap could talk about the real world and not just escapist fun—later landmark tracks might never have found their voice.

One of the surprises of Kurtis Blow is how confidently it veers into styles beyond pure hip-hop. Blow and his producers were eager to prove that this new rap album format could do anything—sometimes to the detriment of artistic consistency. A case in point is “All I Want in This World (Is to Find That Girl).” Coming right after the gritty “Hard Times,” this track is a left turn into sweet soul. Over a slow-dance rhythm with gentle horns and a tinkling melody, Kurtis Blow trades his MC cadence for actual singing—a bold move for a rapper in 1980. The song unfolds as a yearning romantic ballad, with Blow crooning about his search for true love. His vocal style channels a bit of the Chi-Lites, showing that Kurtis had been listening to R&B crooners as much as to funk. It’s a charming idea—essentially a prototype of the rap/R&B fusion that would later dominate charts—but Kurtis’s singing, while earnest, is limited in range. One can sense he’s slightly out of his element, reaching for falsetto notes that just about land. For an MC who built his name on charisma and rhythm, the shift to slow jam crooner is a risky flex. In isolation, it is pleasant enough and historically intriguing. Blow later claimed that his foray into romantic rap here helped inspire LL Cool J’s famous 1987 rap ballad “I Need Love,” planting seeds for the idea that a hardcore rapper could show a vulnerable side.

Kurtis Blow takes an even sharper turn with “Takin’ Care of Business.” Yes, that is the same classic rock anthem originally recorded by Bachman-Turner Overdrive. It’s arguably the album’s most surprising moment: a rap cover of an arena rock song, arriving years before Run-D.M.C. met Aerosmith or before rap-rock was a common crossover. Kurtis Blow’s version can be seen as one of hip-hop’s first flirtations with rock ’n’ roll. The track starts with that signature chugging guitar riff and driving beat, faithfully invoking the original’s energy. Then Blow comes in, not screaming like a rocker but riding the rhythm with his rap verses. He effectively redoes the BTO tune in rap form—keeping the chorus hook (“Takin’ care of business—and working overtime!”) which is chanted (perhaps by backing singers or Blow himself double-tracked) in a catchy call-and-response. It’s a jarring but intriguing blend: the electric guitars and live drums pump with rock intensity, while Kurtis brags and banters in old-school rap fashion.

At one point, he even acknowledges the fusion, yelling something like “Some of y’all didn’t think we could rock like this!”—one imagines baffled rock purists and curious b-boys alike hearing this experiment for the first time. To Kurtis Blow’s credit, the track is fun—it’s clear he’s enjoying smashing genres together. He later reflected that he knew hip-hop could be fused with other forms of music, and that he was the first to do a rock & roll rap, and here’s the evidence on wax. Does it enhance or dilute the album? The answer might depend on the listener. On one hand, it enhances our appreciation of Blow’s fearless creativity—few of his contemporaries would dare go near a hard rock number, and in doing so, he presaged a huge trend of rap-rock crossovers in the decades to come.

The uneven moments on Kurtis Blow are part of its charm and significance. This record captures a transitional moment in hip-hop, when the music was defining its identity on the fly. Kurtis Blow’s debut had no blueprint to follow—it became the blueprint. Hip-hop’s later convention of tightly focused albums with a consistent sound didn’t exist yet. Instead, Blow and his team drew from the broader world of Black music that raised them: James Brown funk, disco grooves, soul balladry, rock riffs—wrapping it all in the new wrapping of rhymes and rhythmic spoken word. The album’s producer, J.B. Moore, even slipped in a Western-themed novelty called “Way Out West,” a cowboy-tinged rap complete with country guitar licks, just to prove that even country & western could meet hip-hop. This kitchen-sink approach means the album wanders stylistically, but it also brims with the excitement of new frontiers. You can almost hear the thought process: rap can go anywhere—why not try it all?

Kurtis Blow was well-received at the time and became hip-hop’s first commercially successful album. It cracked the R&B albums charts and proved to major labels that rap music could sell in long-form. For that alone, its historic importance is guaranteed. Decades later, writers and scholars look back on it as one of rap’s foundational achievements. The album distilled the energy of the live hip-hop experience into a format that future artists realized they could replicate and build upon. It opened the doors for countless others to follow. Kurtis Blow himself became a template for the rap superstar before such a thing truly existed: he went on tour internationally (often as the first rapper people outside New York had ever seen), and he mentored up-and-comers—a young Run (Joseph Simmons) started out as his DJ, even getting a shout-out on the album’s credits. Blow’s success demonstrated that hip-hop wasn’t a fad confined to the inner-city rec rooms; it was a new cultural force that could adapt and thrive on a big stage.

The best way to experience Kurtis Blow in 2025 is to embrace it on its own terms: as a landmark record that wears its aspirations openly. It’s part party record, part social commentary, part experiment in genre-blending—an album trying to be everything hip-hop could be at a time when no one was quite sure what hip-hop albums should be. Some ideas soar, while others falter, but nothing is done by half-measure. For fans and scholars of hip-hop history, the album is essential listening not because it’s flawless—few debut albums are—but because it’s visionary. The album is a snapshot of hip-hop’s first steps into the album era, crackling with the optimism and inventiveness of a genre discovering itself. You’ll hear the occasional clunky transition or a somewhat out-of-tune sung chorus. The rhymes are from a simpler time—Kurtis’s flows are deliberate and unhurried, full of repeated catchphrases and party chants rather than the intricate wordplay that would come in later generations. The trade-off is genuine authenticity and enthusiasm. When Blow shouts “throw your hands in the air!” or exchanges back-and-forth banter with an imagined crowd, it doesn’t feel cliché—in 1980, these devices were fresh, a direct transplant from live hip-hop’s roots.

Kurtis Blow’s debut invites us to appreciate the genesis of recorded rap as both an art and a business. This is the album that gave future pioneers a roadmap—or perhaps a rough sketch of one—from the value of a crossover single like “The Breaks,” to the impact of a socially conscious track, to the willingness to mix styles and seek a broad audience. It even teaches through its missteps: the omission of “Christmas Rappin’” in full reminds us how the industry was still figuring out how to present rap to the masses, and how such decisions can shape an artist’s legacy. Today, we can hear “Christmas Rappin’” alongside Kurtis Blow and get the complete picture of his early work. Youthful, bold, a little unruly, but undeniably groundbreaking. The album remains a vital document of hip-hop’s old school glory.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)