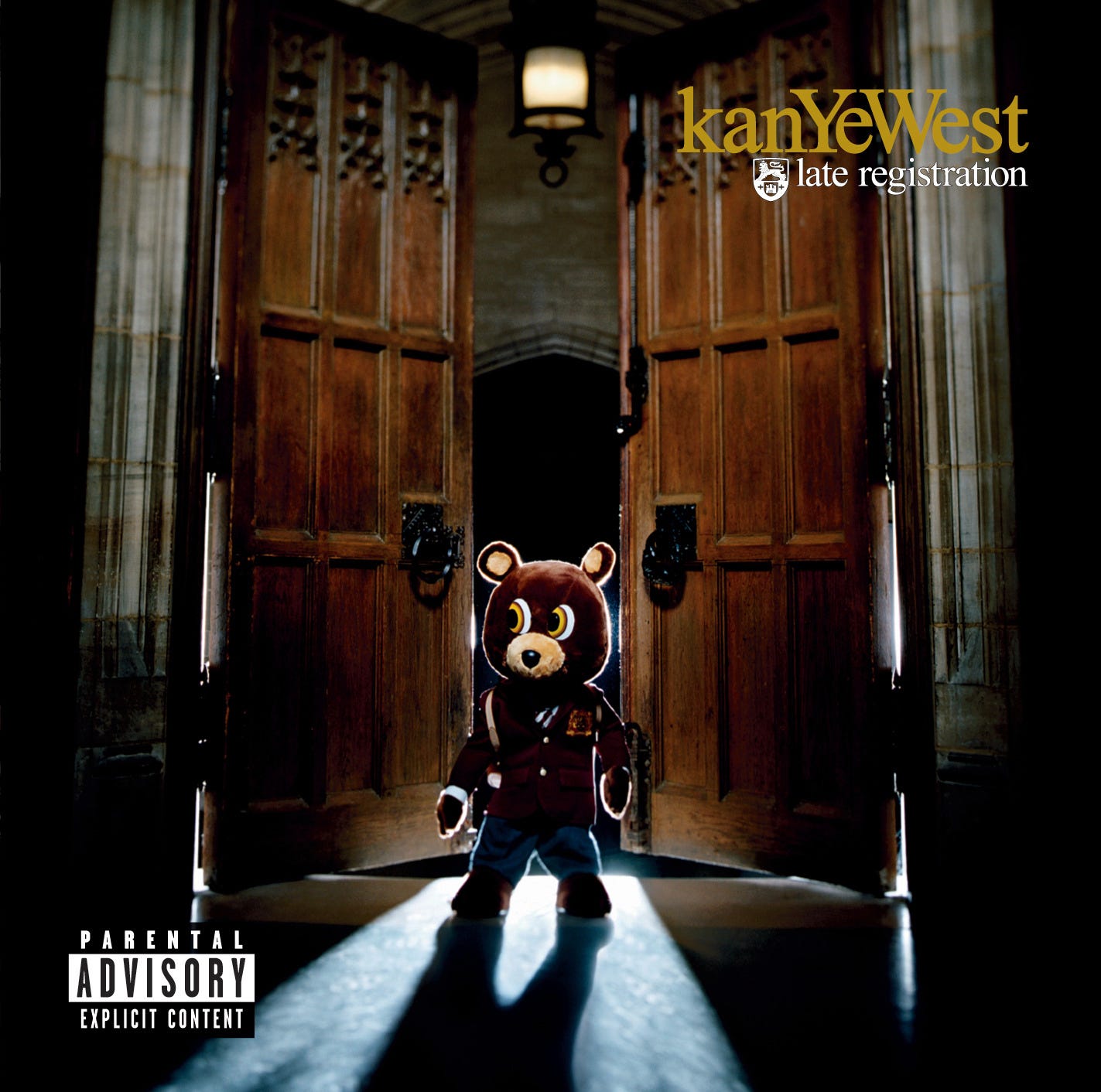

Milestones: Late Registration by Kanye West

Kanye West once asked, “Can I talk my shit again?,” on Late Registration, he did just that. It’s the sound of an artist registering late for class yet somehow ending up at the top of his class.

Kanye West said “sophomore slump, where?” His highly anticipated sophomore album, Late Registration, solidified his evolution from JAY-Z’s inquisitive in-house producer to a superstar rapper-producer in his own right. Arriving a year after his smash debut The College Dropout, this album found West “flipping the script entirely,” enlisting film composer Jon Brion, spending an unprecedented sum on lush studio sessions, and ultimately delivering a critically acclaimed, blockbuster record. The gamble paid off: Late Registration opened at #1 with 860,000 copies in its first week, won the Grammy for Best Rap Album, and proved that West’s artistic vision could translate into pop dominance. Nearly two decades later, the album stands as both a time capsule of mid-2000s hip-hop ambition and a blueprint for how a rapper could straddle the worlds of conscious storytelling and mainstream pop. It was here that Mr. West, raised in a middle-class Chicago household by an English-professor mother, began to fully inhabit the hybrid space he unabashedly claimed: “the digital era’s first pop virtuoso,” as one retrospective dubbed him. Today, revisiting Late Registration offers a rich portrait of an artist marrying soulful hip-hop roots with orchestral sophistication, all while grappling with newfound fame, moral conflict, and unceasing ambition. How do its themes, collaborations, and sonic choices hold up nearly twenty years later?

From the moment the Curtis Mayfield horns of “Touch the Sky” burst through the speakers, Late Registration declares itself both a celebration of classic Black music and a bold expansion of hip-hop’s palette. West had built his name on “chipmunk soul” sampling in the Roc-A-Fella stable, but here he pushed far beyond the sped-up soul loops of his debut, recruiting Jon Brion to infuse his beats with a 20-piece string ensemble and baroque flourishes. Brion, known for his work with Fiona Apple and film soundtracks, helped West experiment with instruments rarely heard on rap records, from celestas and harpsichords to Chinese bells, creating lavish arrangements that were nearly unheard-of in 2005’s hip-hop landscape. On songs such as “Heard ‘Em Say” and “Gone,” Brion’s touch is evident in the layered strings and Elton John-worthy piano lines, giving the album a cinematic quality often described as “sophisticated, baroque hip-hop”. This highbrow musicality was balanced by West’s grounding in gospel, R&B, and boom-bap; he drew on everything from Portishead’s trip-hop to Stevie Wonder’s funk to ensure that, beneath the ornate veneer, the grooves still knocked. The result was an album that felt “expansive” and grandiose yet deeply personal, an “imperfect masterpiece” born of hip-hop bravado meeting conservatory craft.

Jon Brion’s influence on the album cannot be overstated. Without Brion, West later mused, Late Registration might have sounded like a mere sequel to College Dropout—“full of tough horns [and] jacked soul” loops. Instead, Brion provided a composer’s ear and arranger’s toolkit to elevate Kanye’s vision. Take “Hey Mama”: originally a sweet, sample-driven tribute to West’s mother, it was reimagined with moaning vocoder harmonies, tinkling xylophone, and a cascading synth coda courtesy of Brion. These additions somehow didn’t clutter the track; they “inflated and infused” it with new life while preserving its sentimental heart. Similarly, the rousing gospel-rap anthem “Crack Music” was outfitted with a soaring choir and a biblically grand outro—ouches that lend the song an almost ecclesiastical scale. The militant beat and Chuck D references keep it raw, but Brion’s choir makes the final minute feel like a church revival at a political rally. On “We Major,” a celebratory posse cut, West wanted to fuse old-school hip-hop bombast with symphonic pomp; Brion helped “build it up and watch it all fall down” with horn fanfares and swelling strings. The eight-minute track, featuring Nas and Really Doe, plays like a decadent victory lap, its extended instrumental passages practically cinematic in scope. These flourishes demonstrated West’s desire to be seen as a serious musician and composer, not “just” a beat-maker—a point he would drive home in the accompanying live album Late Orchestration, where he performed these songs with an all-female string orchestra at Abbey Road Studios.

Yet, for all the lush instrumentation and high-art aspirations, Late Registration never loses its hip-hop soul. There’s a dynamic tension between the “hip-hop rawness” Kanye cherishes and the “pop sophistication” Brion brings, and the album thrives in that middle ground. At times the marriage is seamless: “Drive Slow,” for instance, rides a woozy G-funk bassline and DJ Screw-inspired slow-down at the end, preserving a gritty Southern rap feel even as muted trumpets accent the groove. In other moments, the polish threatens to overshadow the rap core – something even fans noted when the album dropped. “Bring Me Down,” a defiant track featuring Brandy, is drenched in dramatic strings that some found overwrought, even “silly orchestral pomp” that risked drowning the emotion. It’s one of the rare moments where West’s reach may have exceeded his grasp; the track’s glossy sheen and Brandy’s filtered vocals feel a bit dated now, epitomizing mid-2000s pop-R&B trends more than timeless hip-hop. But these are minor missteps on an album that mostly balances grandeur with grit. For every lavishly arranged outro (most songs here enjoy extended codas to “breathe” and sink in), there’s a hard-hitting beat or streetwise guest verse to keep things grounded. Late Registration expanded the scale of hip-hop, but it still makes your head nod.

Beyond its sonics, Late Registration resonates for its thematic depth and lyrical content, which were groundbreaking for a pop-rap album of its era. West’s lyrics throughout are powered by the tensions in his persona: braggadocio and insecurity, materialism and conscience, celebration and introspection. This was a rapper who, unlike many of his peers, did not come from the streets, and he turned that to his advantage by exploring subject matter outside the gangsta realm. The album finds Kanye grappling with real-world issues that still reverberate today, albeit through a 2005 lens. On “Heard ’Em Say,” the gentle opening song with Maroon 5’s Adam Levine crooning the hook, West adopts the perspective of everyday people struggling to get by. Over light piano and brushed drums, he muses about family health scares and urban poverty, “Before you ask me to go get a job today, can I at least get a raise on the minimum wage?” he pleads, capturing a working-class frustration. He was writing about his own experiences and observations as a middle-class kid who saw both privilege and hardship, and it gave his music a relatable everyman quality that rap’s ultra-luxury fantasies often lacked. That said, Kanye was never shy about aspiring to those luxuries, and Late Registration’s most fascinating lyrical turn is how he acknowledges the moral ambivalence of his success.

Nowhere is this more evident than on “Diamonds from Sierra Leone,” the album’s lead single and a microcosm of Kanye’s evolution. Initially conceived as a swaggering ode to Roc-A-Fella Records (hence the “throw your diamonds in the sky” hook), the song took a sharp turn when West learned about the blood diamond trade in Africa. He re-recorded his verses to address the issue, connecting his conspicuous bling to the civil wars funded by diamond profits. Over a haunting sample of Shirley Bassey’s “Diamonds Are Forever”, Kanye’s lyrics swing from triumphant to contrite. “Good morning, this ain’t Vietnam, still/People lose hands, legs, arms for real,” he raps with awakening conscience, admitting that “little was known of Sierra Leone” in his circles. In one couplet, he captures the ignorance many Americans (himself included) had about the human cost behind their jewelry. The most telling line, however, comes soon after: “People askin’ me if I’m gon’ give my chain back/That’ll be the same day I give the game back”. West lays bare his conflict, he knows the truth now, but he’s not about to renounce the spoils of his stardom. At the time, this blend of conscience and materialism felt refreshing and bold; West was virtually alone among platinum rappers in even mentioning conflict diamonds or criticisms of consumerism.

The album’s social consciousness doesn’t end there. Late Registration is threaded with commentary on institutional racism, poverty, and the Black experience in America. “Crack Music,” co-starring The Game, flips the narrative of the 1980s crack epidemic, positing the conspiracy theory that the government had a hand in flooding Black neighborhoods with drugs, “system broken, the schools closed, the prison’s open,” West growls, tying together racism and mass incarceration. He calls this music “our music,” a substance just as powerful as the crack itself, and in doing so, aligns himself with the legacy of political hip-hop (Public Enemy, N.W.A.) while updating it for the Bush era. On “Roses,” Kanye delivers one of his most heartfelt verses ever, recounting his family’s vigil over his ailing grandmother in the hospital. He confronts the cold economics of healthcare in America (“If Magic Johnson got a cure for AIDS… and all the broke motherfuckers passed away,” his cousin sorrowfully quips in the song), and the institutional inequities that decide who lives or dies. Nearly twenty years later, in a world still plagued by healthcare disparities, “Roses” remains deeply moving, a reminder that West’s middle-class upbringing (as the son of a college professor) gave him a window into both privilege and precarity.

His blend of vulnerability and critique on that song exemplifies how Late Registration engaged with social issues in a personal way. Even the skits, often dismissed as filler, serve a thematic purpose. The “Broke Phi Broke” interludes parody a fictitious fraternity of the poor, a tongue-in-cheek jab at the “poverty pride” mentality and a comment on Kanye’s own guilt and drive to never go back to having nothing. In hindsight, the skits’ humor is a bit broad, but they underscore West’s awareness of straddling two worlds, the broke past and the flashy present. And for every heavy moment, Kanye counterbalances with levity and braggadocio, reminding us that he hasn’t abandoned fun. “Gold Digger,” the album’s biggest hit, is a prime example. Built on an irresistible Ray Charles sample (Jamie Foxx channeling Charles’s voice on the hook) and a swinging beat, the song finds Kanye adopting a playful storytelling flow about women after his money. It’s satirical and comedic, “She got a baby by Busta? My best friend say she use to fuck with Usher,” but beneath the jokes lies a commentary on relationships and ambition. In one oft-quoted verse, West describes a faithful woman supporting a man with potential: “He got that ambition, baby, look at his eyes/This week he moppin’ floors, next week it’s the fries… so stick by his side”, only to observe cynically, “When he get on, he leave yo’ ass for a white girl.” Well…

With that one line, Kanye critiques a real social phenomenon with a knowing smirk. It’s a testament to his lyrical approach in this era—accessible, catchy, and funny, yet pointed in its observations. The rhyme schemes on “Gold Digger” (and across the album) aren’t dense; instead, West uses simple, familiar flows to ensure his punchlines and messages land clearly. That choice helped make these songs anthemic and memorable. Even now, who can resist finishing the line “...she ain’t messin’ with no broke broke” when the song comes on? Kanye’s early rap style may not have been the most technically dazzling, but its clarity and personality were its strengths. These flows, sometimes derided as sing-songy or basic by his critics, read now as charming hallmarks of his early style, the voice of a rapper who hadn’t yet cloaked himself in heavy autotune or abrasive distortion. There’s an earnestness and approachability in the way Kanye rapped on Late Registration that, in retrospect, many find refreshing.

Still, West was savvy enough to surround himself with top-tier lyricists to complement his verses—a move that both bolstered the album’s rap credibility and highlighted Kanye’s understanding of his own limits. Late Registration is studded with guest appearances that feel like a curated tour of hip-hop’s landscape circa 2005. JAY-Z and Nas, fresh off their legendary feud’s resolution, both show up (though JAY-Z only appears on the “Diamonds” remix, his presence looms large). Having Nas and Jay on the same album was a flex that signaled Kanye’s clout. Common, a fellow conscious rapper from Chicago, drops a sober verse on “My Way Home,” essentially taking over that entire track with a Gil Scott-Heron sample looped underneath, an unorthodox choice that nevertheless adds gravitas to the album’s midsection. Cam’ron, at the height of his Diplomats fame, injects “Gone” with witty, swaggering nonchalance (“I’m back by unpopular demand,” he sneers, stealing the show), while up-and-comer Consequence lends additional verses to flesh out Kanye’s ideas. Even Paul Wall, the Texas mixtape star, pops up on “Drive Slow” to give it some Southern drawl authenticity, and famously rhymes “insinuate” with “caterpillar” in a surprisingly intricate 16 bars. Kanye deftly orchestrates these features, often letting them play to their strengths: he knew Common’s reflective tone would suit the melancholic mood of “My Way Home,” just as he knew Cam’ron’s flamboyant wordplay would bring “Gone” to a climactic peak.

In the grand scheme of Kanye West’s career, Late Registration occupies a somewhat intriguing space. It is less mythologized than his debut, The College Dropout, which carries the legend of the underdog who revolutionized mainstream rap’s subject matter. It is also less discussed than the audacious stylistic overhauls of later albums like 808s & Heartbreak or Yeezus, or the maximalist magnum opus of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. But to consider Late Registration Kanye’s “forgotten” classic would be a mistake, the album was hugely successful and critically adored in its time, and it remains a cornerstone of 2000s hip-hop. It didn’t introduce a complete aesthetic paradigm shift in the way some other Kanye albums did, but it masterfully refined and expanded the unique lane he had carved out.

In 2005, Kanye West was intent on proving that his initial success was no fluke; that he could evolve artistically and still dominate the charts. Late Registration achieved exactly that. In doing so, it helped pave the way for hip-hop’s full-fledged embrace of album-oriented artistry on a pop scale. When West boldly declared, “I am a pop artist” a decade later, he was reflecting a reality that Late Registration had set in motion; the idea that a rapper could be as comfortable at the top of the pop charts as on the rap battle stage, without sacrificing authenticity. Back in 2005, some bristled at West’s pop instincts (was it sacrilege to have the singer of Maroon 5 crooning on a hip-hop record?), but his instincts proved prescient. Today’s musical landscape, where rap is pop music, owes a debt to the trails Kanye blazed. Late Registration even foresaw the grand, genre-blending spectacles that artists routinely attempt now.

It is a rewarding experience listening to Late Registration precisely because it captures Kanye West at a pivotal moment of transformation before he became a MAGA and Nazi elitist. He was young enough that his music carried a wide-eyed, hungry energy—the audacity of a man who survived a near-fatal car crash and was rapping with his jaw wired shut just to get heard, now suddenly finding himself on the world stage. Yet he was also mature enough to attempt weighty themes and push the genre’s boundaries in a way few of his contemporaries dared. You can hear that unceasing ambition in every corner of the record, from the opulent production to the oscillation between self-aggrandizement and self-examination in the lyrics. Some of the flows and punchlines that felt so cutting-edge in 2005 (“George Bush doesn’t care about Black people,” he ad-libbed around this era, shocking the world) may now scan as products of their time, but the spirit of innovation in the music is timeless. It solidified his transition from the kid who “just made beats” into a full-fledged artist who could stand on Oprah’s stage or rock a stadium in a Louis Vuitton blazer (both of which he did, around the time of this album). And fittingly, in straddling the underground and the mainstream, the conscious and the commercial, Kanye didn’t just declare himself “pop,” he bent the definition of pop to include what he was doing.

Whether it’s the goosebumps of hearing those triumphant horns on “Touch the Sky,” the lump in one’s throat during “Hey Mama,” or the contemplative head-nod to the strings of “Gone,” the album has an emotional richness that transcends eras. “Everybody feels a way about K, but at least y’all feel something,” Kanye notes on “Bring Me Down,” paraphrasing a line that acknowledges his polarizing impact. That sentiment rings even truer today. Our understanding of Kanye West has changed dramatically in the years since—he has ascended to heights and weathered controversies that cast a different light on his early material. Listening now, one might hear Late Registration with a tinge of nostalgia for the old Kanye—the pink Polo-wearing, soul-sampling kid with a chip on his shoulder and genius on his mind.

But the album itself hasn’t lost its potency. If anything, the nearly two decades of hindsight allow us to appreciate its craft and foresight even more. We can hear how its themes of ambition, social commentary, and personal struggle were harbingers of topics that dominate today’s music. We can marvel at how its blend of sharp pop instincts and hip-hop authenticity prefigured the genre’s future. And we can simply enjoy it as a collection of great songs that hit that sweet spot between head and heart. Kanye once asked, “Can I talk my shit again?,” he did just that, crafting an album that still speaks volumes. Nearly twenty years later, it remains a touchstone in hip-hop, the sound of an artist registering late for class yet somehow ending up at the top of his class, setting the curriculum for those who followed.

Standout (★★★★½)