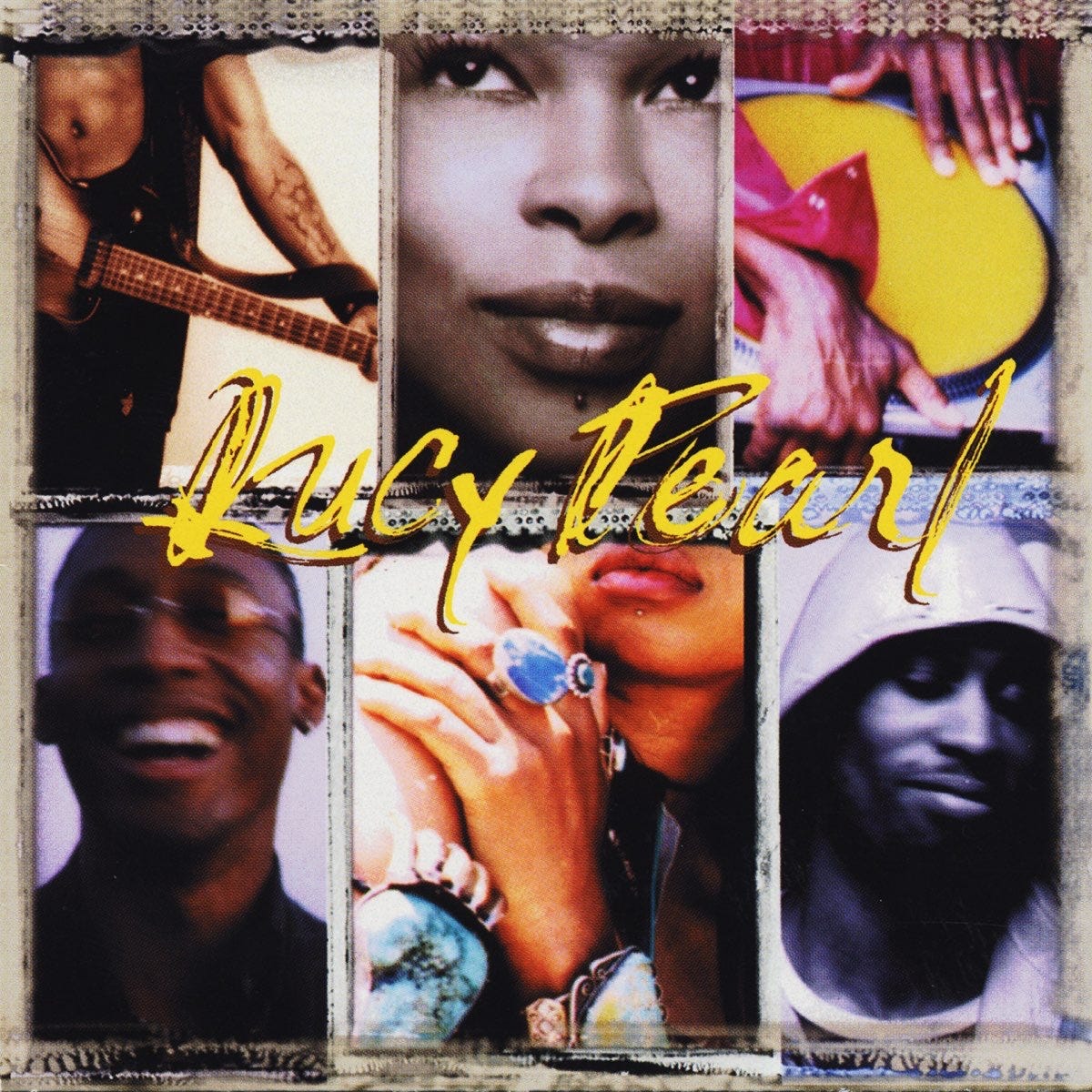

Milestones: Lucy Pearl by Lucy Pearl

Lucy Pearl sounded like three friends testing whether their individual histories could coexist within one groove, and for fifty-five minutes, proving the answer was yes.

Lucy Pearl exists in that brief, electric moment when R&B and hip-hop were renegotiating their relationship at the dawn of the millennium. By spring 2000, Raphael Saadiq, Dawn Robinson, and Ali Shaheed Muhammad had each completed an influential 1990s run—Saadiq as the bassist and arranger of Tony! Toni! Toné!, Robinson as the powerhouse voice anchoring En Vogue’s feminist anthems, Muhammad as the mellow architect of A Tribe Called Quest’s jazz-rap swing—and all three were restless. Saadiq phoned the others with a one-off proposal: make a record from scratch, tour it, then walk away. The super-group formally assembled in 1999 and took the deliberately femme name “Lucy Pearl,” a nod, Robinson once said, to something “timeless, glamorous and tough all at once.”

Their self-titled album, recorded over late 1999 and early 2000 and released on Beyond/EMI, sounds like a conference where New Jack swing, neo-soul, left-field hip-hop, and 1970s analog warmth all exchanged business cards. Saadiq’s P-Bass anchors almost every groove with roomy, unquantized low-end; Muhammad’s MPC slaps dusty snares beside live drums; Robinson stacks gospel-rich harmonies above them, sometimes sweet, sometimes serrated. Instead of shoe-horning their old trademarks into neat verses, they sample themselves: the opener “Lucy Pearl’s Way” re-interpolates Saadiq’s own “Ask of You” and slices the chord change from Tribe’s “Electric Relaxation,” literally braiding their pasts into a new beginning. That self-quotation becomes heritage music constructed in real time, bridging the analog ideals of the 1990s with the digital eclecticism that would dominate the 2000s.

“Dance Tonight,” conceived as a no-stress invitation to reconnect after Y2K anxiety, proved the perfect handshake single. Its Fender Rhodes progression circles like a block-party chant while Robinson and Saadiq trade smiles in the hook (“I wanna dance tonight/I wanna toast tonight”) foreshadowing the two-step bounce that would soon define early-2000s R&B. The song peaked at No. 36 on both the Hot 100 and UK singles charts and earned a Grammy nod, but the charm is inside the mix: Saadiq plays a clipped slap-bass riff straight out of Oakland funk while Muhammad pans vinyl scratches left-right, evoking Tribe’s headphone aesthetic. Even the video, which splices their own earlier clips with images from Love & Basketball, positions Lucy Pearl as both a retrospective and a futuristic entity.

That tightrope between nostalgia and novelty snaps taut on “Don’t Mess with My Man,” a three-minute master-class in tension. The beat rides a muted guitar down-stroke reminiscent of Chic, yet Muhammad overlays a filtered synth-bass line hinting at the coming bling-era minimalism. Robinson’s lyric flips a classic quiet-storm trope into a warning: “Don’t mess with my man/I’m a be the one to bring it to ya,” her melismatic ascent gliding over Saadiq’s lower-register ad-libs. Although the single performed better overseas, it also previewed the assertive, woman-centered messaging that would course through R&B in the Beyoncé/Ashanti era.

“Without You” pivots to heartbreak, layering Saadiq’s plaintive falsetto over a guitar figure that nods to Prince’s Sign o’ the Times palette. Just as neo-soul was cresting, the song’s chord extensions and live string flourishes mirror that scene, but Muhammad lines the drums with phased hi-hats that foreshadow the jiggy shuffle of Jagged Edge and 112. The album’s final single, “You,” ropes in Q-Tip and Snoop Dogg—East-Coast jazz-rap and West-Coast G-funk royalty—over DJ Battlecat’s sub-bass, completing Saadiq’s plan to make the record feel like “your whole CD changer on one disc.” Tip’s elastic internal rhymes trade places with Snoop’s half-sung drawl, and Robinson returns only on the harmonic tag, allowing the men’s cadences to intersect without ego—an intentional reversal of the chorus-verse hierarchy dominating radio at the time.

Deep cuts are where the trio’s chemistry feels least scripted. “Trippin’” floats a call-and-response refrain above diatonic bass drops, capturing the butterflies of new lust; Robinson’s playful scatting ping-pongs with Saadiq’s hypeman grunts so tightly that one could mistake them for an old Motown duo updated with MPC swing. “La La” is all crate-digging joy: Muhammad chops an electric-sitár lick, Saadiq drapes sub-bass beneath, and Robinson riffs about endless summers while their three-part hook drifts, wordless, like a lost Ohio Players outro. On “Good Love,” they stack hand claps under a 6/8 pocket, foreshadowing the broken-beat resurgence then incubating in London; Robinson’s line “You give me that Marvin kind of feeling” situates the track within a lineage even as the rhythm reaches forward.

The album’s most revealing moment is “They Can’t,” where Muhammad samples the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Long Kiss Goodnight” vocal sighs, then pairs them with Saadiq’s dark Wurlitzer chords; Robinson counters with a gospel-shaped melody about perseverance: “They tried to funk with us/But they can’t put a stop to us.” The lyric resonates because each member had recently waged painful label battles—Saadiq’s Tony! Toni! Toné! split, Robinson’s exit from En Vogue, Muhammad’s frustration after Tribe’s farewell LP—and Lucy Pearl, for a moment, let them reassert agency through collective authorship.

Saadiq’s fingerprints, unsurprisingly, cover every frequency. His bass phrasing invokes Larry Graham snapshots—slides, thumb pops, ghost notes—yet he resists solo-ist indulgence, tightening each line until it serves the vocal story. Robinson, freed from En Vogue’s doo-wop-tight harmonies, explores texture rather than range: sometimes husky (“Hollywood”), occasionally airy (“Everyday”), sometimes snarling (“Can’t Stand Your Mother,” a comic sketch that swings harder than its title suggests). Muhammad, meanwhile, rebuilds Tribe’s jazz breaks within a more polished R&B framework; his strategic rim shots, vinyl hiss, and percussive turntable flicks keep the album from sounding like a pristine studio exercise. In short, each index talent is audible, but never at the expense of the whole; the secret sauce is restraint.

Context helps explain the record’s alchemy. By 2000, R&B was splintering: Timbaland’s stutter-beats, the Neptunes’ synth minimalism, and Destiny’s Child’s melismatic pop all competed for attention. Lucy Pearl responded by synthesizing older forms—Seventies choruses, church chord progressions, live bass—with hip-hop’s sample logic and then-modern engineering sheen, offering a blueprint later expanded by Alicia Keys’ early work and Saadiq’s own Instant Vintage. The album quickly went Gold in the U.S. and stood as the trio’s lone statement before Robinson departed that October and the group dissolved the following year. Internally, there was friction over royalties and leadership. Robinson has since described losing her house amid the fallout, while Muhammad told NPR he wished egos had been checked at the door, but the music never betrays that turmoil.

Their eponymous debut still feels like a hinge. The last great analog-minded R&B album to debut before Pro Tools-era pitch correction became ubiquitous, and an early signpost for the neo-soul/hip-hop hybrids that dominated the 2000s. Its grooves breathe, its samples wink, its lyrics locate desire, jealousy and reconciliation in everyday language—“Keep your hands off my man,” “I wanna dance tonight,” “I can’t stand your mother”—lines simple enough to loop in your head yet complex enough to reveal new harmonic pockets with each listen. Most super-groups sound like board-room experiments; Lucy Pearl sounded like three friends testing whether their individual histories could coexist within one groove, and for fifty-five minutes, proving the answer was yes. Their unity was fleeting, but the result remains a sonic snapshot of transition—a passport stamped with every style that mattered on the journey from 1990s classicism to 2000s futurism —and a reminder that sometimes the most resonant statements are the ones delivered and then left to echo.

Standout (★★★★½)