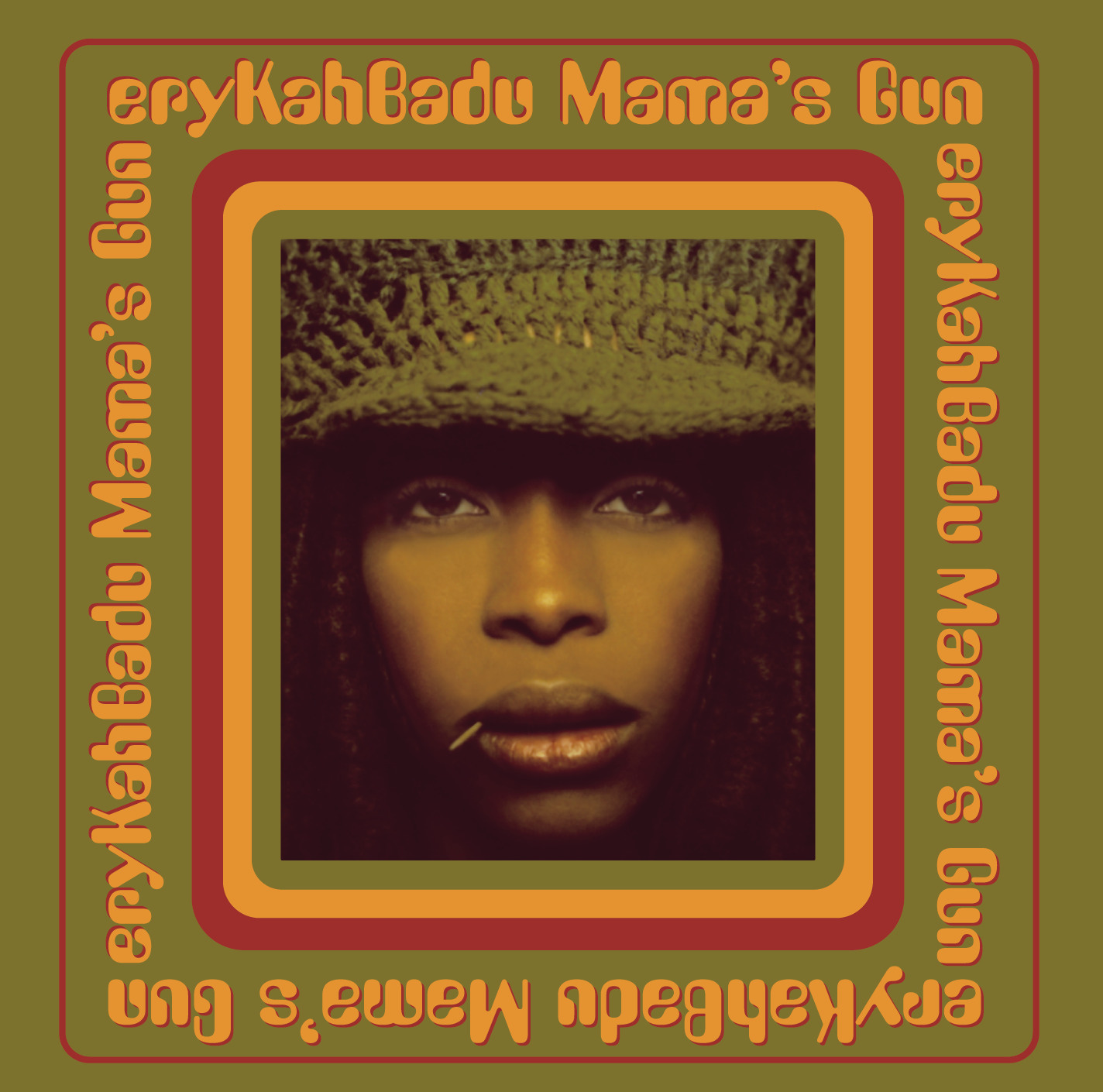

Milestones: Mama’s Gun by Erykah Badu

Great Black music as the past, present, and future conversing together over a beat. Mama’s Gun is exactly that. It’s Afrocentric and funky, spiritual and irreverent, feminine and unflinching.

As the world held its breath through Y2K anxieties and post-millennial uncertainty, Erykah Badu was busy crafting an album that absorbed those tremors and responded with visionary soul. Mama’s Gun, released in November 2000, feels inextricably of its moment—the tail end of an era and the start of a new one—yet it also sounds timeless. It arose during neo-soul’s golden age, alongside kindred projects like D’Angelo’s Voodoo (we still can’t believe he’s gone) and Common’s Like Water for Chocolate. In fact, all three albums were incubated simultaneously at New York’s Electric Lady Studios by the loose collective known as the Soulquarians, with drummer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, keyboardist James Poyser, bassist Pino Palladino, and engineer Russell Elevado at the core. Badu walked into those storied studios (the house that Jimi Hendrix built) fully aware of the zeitgeist: the extended periods of unease and vigilance that defined the year 2000—from contested elections and police brutality trials to a jittery new-millennium uncertainty. With Mama’s Gun, she channeled that restless energy into a record that was warm and familiar on the surface, yet defiantly modern and unflinchingly honest at its heart.

Badu’s 1997 debut, Baduizm, had established her as the ethereal bohemian voice of neo-soul, all incense, headwraps, and cryptic, poetic musings. Mama’s Gun retained Badu’s spiritual and Afrocentric core—her songs still referenced Five Percent Nation lessons and distant planets—but this time she brought the message down to earth. In interviews, Badu described Mama’s Gun as something young Black boys and girls could carry “for protection,” suggesting an album as personal armament. It was her first studio project as a mother (Badu gave birth to a son, Seven, with Outkast’s André 3000 in 1997), and her femininity and newfound life experience course through the music. Where Baduizm couched its ideas in metaphor, Mama’s Gun speaks more directly about the trials of daily life, love, and Black womanhood. There’s urgency here—a need to address the tug-of-war between rage and despair. Yet Badu’s way of confronting harsh reality is never didactic. It’s by wrapping truth in groove, by making the medicine go down smooth with a head-nodding beat and a haunting melody.

The Soulquarian sound—vintage vibes, future vision: Much of Mama’s Gun’s magic lies in its sound: that rich, full-band warmth that feels analog and alive. Questlove, Poyser, Palladino and company approached these sessions like a 1970s jam, drawing on vintage recording techniques to summon the spirit of heroes like Stevie Wonder, Funkadelic, and Roy Ayers. In fact, they literally dusted off Stevie Wonder’s old Fender Rhodes keyboard at Electric Lady and put it to use; Questlove set aside his modern drum triggers and picked up a 1968 Ludwig kit, relearning how to play softly so that the drums would sing on tape. Pino Palladino thumped a classic Fender Precision bass from the 1950s, and Elevado miked it all with old-school Royer ribbon microphones. The result is an album that sounds like a lost soul gem from the analog era—deep-pocketed bass grooves, buttery Rhodes chords, tape-saturated warmth—yet feels utterly present in its content. Elevado, who mixed Mama’s Gunas well as Voodoo and Like Water for Chocolate, imbued all three records with this nostalgic sonic character, nodding to the lineage of earlier records while the musicians kept their eyes on contemporary concerns. Neo-soul was at its peak in this moment, driven by young Black artists reviving the sound of their parents’ vinyl records to speak to a new generation. Badu stood at the forefront of that movement. With Mama’s Gun, she both fulfilled the promises of Baduizm and broke free of neo-soul’s confines—expanding its scope to include more funk bite, jazz improvisation, and raw lyrical frankness.

These are the little daily worries of any ordinary life, especially a young single mother trying to balance art and home. It’s a subtle, intimate moment—the sound of a woman’s mind racing in the quiet before chaos. Then boom—a blast of pure funk shatters the quiet. The opener “Penitentiary Philosophy” comes roaring in on a crunchy guitar riff, a squall of Rufus-style soul-rock vocals, and Questlove’s drums slamming in tight unison. The jolt is deliberate and thrilling. Badu doesn’t ease us in gently; she kicks down the door. “Penitentiary Philosophy” is a six-minute funk-rock storm that immediately dispels any notion of a mellow sequel to Baduizm. Its riff-driven groove and distorted edge owe more to Maggot Brain-era Funkadelic than to the languid neo-soul of Badu’s earlier work. Badu herself is front and center as an impassioned truth-teller. Adopting, in her own words, the stance of a “warrior princess,” she delivers verses that rail against mental and societal imprisonment. Her words channel the spoken-word fury of Gil Scott-Heron and the immediacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail (which she paraphrases, insisting that liberation cannot wait). In the year 2000, television audiences were tuning into David Simon’s gritty urban docudrama The Corner and, soon after, The Wire; in Badu’s musical world, she was offering a parallel critique, singing of “streets that don’t love you” and the plight of young Black men caught in cyclical traps.

Set to a breezy mid-tempo groove that recalls Soul II Soul’s uplifting club-soul vibe, “Time’s a Wastin’” finds Badu gently admonishing her community (and herself) to stop standing still. “You've got to get up, get out, and do it,” she urges in the spirit of an older sister or a wise auntie. “Make your money last, learn from your past… Don’t let nobody slow you down,” she sings, elongating her phrases with a comforting lilt. The track’s music carries the message. Poyser’s Fender Rhodes chords pulse warmly, and at the bridge, a churchy organ swells beneath Badu’s vocal, evoking the feeling of a Sunday service where the preacher improvises encouragement over the band. Indeed, the interplay of her voice with that subtle organ vamp feels like a nod to the Black church tradition—what scholar Ashon Crawley calls the “nothing music” that underlies a pastor’s sermon. The sermon is Badu’s own plea to “keep on movin’” (an intentional echo of Soul II Soul’s anthem “Keep on Movin’”). “Time’s a Wastin’” is, in effect, the hopeful flipside to “Penitentiary Philosophy.” With this song, a light shines forward, suggesting that through diligence, self-improvement, and collective positivity (“oh, baby, we need to smile”), a better future is still within reach.

Yet Mama’s Gun is far from a two-note album of just anger and advice. Its genius is how Badu balances languid, soul-soaked grooves with incisive, socially charged lyrics, without ever turning preachy or losing the listener’s ear. After the one-two punch of the opening tracks, the record downshifts into a stretch of subdued, introspective songs—rich in vibe, layered in meaning. “Didn’t Cha Know?” floats in on a lazy, hypnotic bassline and a sample of Tarika Blue’s ethereal 1970s jazz-funk tune “Dreamflower.” Co-written and produced by the late J Dilla (one of the Soulquarians’ secret weapons), the song wraps Badu’s voice in a hazy atmosphere of Aquarius-age psychedelia. But listen closely: she’s grappling with uncertainty and regret, confessing, “I think I made a wrong turn back there somewhere.” The lyrics acknowledge confusion and wandering—and notably, they refuse to offer easy answers. Didn’t cha know life would be this challenging? Badu seems to ask. Sometimes we lose our way, and that’s okay. There’s a humility in this songwriting, a willingness to admit not knowing, which was itself a quiet rebuke to the “Oprah-fied” self-help culture of the time that peddled sure-fire solutions.

The continuum of tracks with “…& On” (a sequel to her debut single “On & On”) and “Cleva” continue in the vein of laid-back, in-the-pocket soul while showcasing Badu’s quirky charisma and humor. On “…& On,” she playfully extends the life philosophy of the earlier song—“my cipher keeps moving like a rolling stone,” she sang in 1997, and here she’s still rolling, still dropping knowledge amidst jazzy Nuyorican Café-style spoken-word flows. She references world history and spiritual lessons in oblique snippets, embodying the boho hip-hop poet persona that endeared her to fans early on. “Cleva,” by contrast, is wonderfully specific: over a slinky, minimalist groove accented by Roy Ayers’ shimmering vibraphone tones, Badu serves up a self-love anthem that’s equal parts funny and empowering. “This is how I look without makeup,” she croons coyly, going on to joke about how her breasts (“my ninnies”) sag when she doesn’t wear a bra, and how her hair never quite reaches her shoulders. By conventional standards of R&B divadom, these are “flaws,” but Badu turns them into a celebration. “But I’m cleva,” she proclaims—clever in mind, comfortable in her skin—and that means far more than superficial beauty. The track’s arrangement stays mellow and confident, allowing her personality to shine through every witty ad-lib and aside. In a music industry that often pressured Black women to present a polished, hyper-glamorous image, Badu’s Cleva stance was practically radical: she flaunted her natural, homegirl realness and made it sublime.

Importantly, she did it without a trace of bitterness or envy. In the very next song, the cheeky funk jam “Booty,” Badu assures a romantic rival that “your booty might be bigger, but I still can pull your nigga—but I don’t want him”, because “you don’t need him” either. It’s a sly, comical diss track and a note of sisterly solidarity rolled into one. Badu’s sense of humor on Mama’s Gun keeps the album from drowning in its own seriousness. She lets us exhale and laugh, even as she delivers serious truths about self-worth. The centerpiece of the album’s second half is undoubtedly “Bag Lady,” the song that became Mama’s Gun’s biggest commercial success and a lasting cultural touchstone. With its breezy acoustic guitar loops and toe-tapping beat, Erykah Badu addresses the emotional baggage that so many women (indeed, so many people) accumulate—past hurts, grudges, fears—and crafts a soulful directive to let it go. “Bag lady, you gon’ hurt your back, draggin’ all them bags like that,” she sings in the opening lines, her tone simultaneously sympathetic and gently chiding. “I guess nobody ever told you all you must hold on to is you, is you, is you,” goes the hook, distilling the song’s wisdom: prioritize self-care and self-possession over the weight of old pain.

The song’s music video, directed by Badu herself, is a loving tribute to Ntozake Shange’s landmark 1975 choreopoem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf. In Shange’s work—a collection of poetic monologues set to music and dance—seven women named only by colors (Lady in Red, Lady in Blue, etc.) share their traumas and triumphs, ultimately finding solidarity and healing. Badu’s video for “Bag Lady” re-stages key imagery from For Colored Girls: she appears as the Lady in Red, alongside four other women in blue, green, purple, and orange (streamlining Shange’s seven down to five). They move through scenes that mirror the choreopoem’s arc—from the city streets where burdens are carried, to a communal space of learning (a classroom), and finally to a church where release and salvation are attained. In one powerful moment, as Badu sings “all you must hold on to is you,” each woman in the video literally shrugs off the heavy bags she’s been carrying and drops them to the floor, their faces transforming from weariness to relief. The symbolism is clear and resonant.

In the final act of Mama’s Gun, Badu turns her gaze to mortality, legacy, and the deepest chambers of the heart. “A.D. 2000” is the album’s quiet storm—a gently swaying, achingly beautiful tribute with a razor’s edge of political protest. The title, on the surface, simply marks the year of the album’s creation, but it doubles as an homage to Amadou Diallo, the 23-year-old Guinean immigrant whose 1999 killing by four New York City police officers sparked national outrage. (The initials A.D. also correspond to Diallo’s name, and the song’s mournful refrain—“No you won’t be namin’ no buildings after me”—alludes to the anonymity and disregard so often afforded Black lives lost to violence.) “If they won’t be namin’ no buildings after you,” she implies, “at least we have this song.” Thirteen years before the phrase “Black Lives Matter” would resound as a rallying cry, Badu was already mourning the reality that Black lives were treated as expendable and insisting that the fallen be remembered. In the bridge of the song, a delicate harmony floats in—provided by soul legend Betty Wright, whom Badu enlisted for this track. It’s as if Badu is saying: Black women see this injustice too, and we bear witness together. When Mama’s Gun was released, the police who shot Diallo had just been acquitted, deepening the community’s despair.

And then, after all the cosmic philosophizing, social commentary, humor, and righteous fury, Erykah Badu chose to close Mama’s Gun with herself—raw, unguarded, and human. The album’s final track, “Green Eyes,” is a 10-minute odyssey through the rise and fall of a relationship, widely understood to be inspired by Badu’s breakup with André 3000 of OutKast. It stands as one of Badu’s most stunning achievements, a song-suite in three movements that plays like a short film or a one-woman stage musical. Badu even explicitly labeled the sections Denial, Acceptance, and Relapse, signaling the emotional stages she journeys through. In the first movement, she embodies heartbroken denial with theatrical flair: the music mimics an old-time jazz lounge piano in a wistful major key, a muted trumpet wah-wahing in the background—as Badu deliberately affects a cracked, vintage vocal tone, as if she’s singing through a gramophone. “My eyes are green ’cause I eat a lot of vegetables,” she sings coyly, an absurdist excuse to explain away the obvious hurt of jealousy. “It don’t have nothing to do with your new friend.” It’s a marvelously literary line—she’s essentially narrating her own denial, play-acting the part of the unbothered ex. But as anyone who’s gone through heartbreak knows, denial is fleeting.

After a few minutes, the song shifts: the tempo subtly picks up, the chords change, and Badu’s vocals lose their retro filter, becoming clearer, closer, more present. We’ve entered the Acceptance phase, though it’s really more like a confrontation with reality. “I’m insecure… but I can’t help it,” she admits plainly, her tone now modern and vulnerable. The band—which had been holding back—joins in fully here, as if to support her in this moment of truth-telling. Poyser’s piano and Palladino’s bass underline each confession. Badu’s lyrics in this section lay her pain bare: she sings of her mind telling her to move on while her heart lags behind, and finally, in a breathy, cracking voice, she musters the strength to say “I don’t love you anymore.” It’s a gut-punch, both to the listener and seemingly to herself—you can hear the tears in the way she hovers over the word “anymore.” As if that emotional peak wasn’t enough, “Green Eyes” has one more act. The music halts for a brief moment (a classic false ending, like the pause before the encore), then returns with a bluesy vengeance.

Enter Relapse: the final few minutes explode into a rollicking, almost gospel-infused jam. Badu’s voice turns fiery and defiant, belting and scatting with a mix of anger, sarcasm, and wounded pride. Horns riff in the background, Questlove’s drums snap with renewed energy. Badu vacillates between castigating herself for being so naïve and blasting her ex for not meeting her needs. “You’re the selfish one,” she cries out, flipping the narrative of blame. A fluttering flute solo flits by—a last touch of whimsy amidst the emotional wreckage—and then the groove slows and settles as Badu reaches her final epiphany. In the song’s dying moments, she realizes that her heartbreak, her “breakdown,” has as much to do with her partner’s shortcomings as with her own. “Y’all know nothing, nothing about it… I know you’re cheatin’,” she intones, almost laughing at herself for how blind she had been. With that, Mama’s Gun ends not on a note of tidy closure, but with a kind of hard-won clarity.

Mama’s Gun is a high-water mark not just for Erykah Badu’s career but for the entire neo-soul movement and the state of Black music at the turn of the century. It’s an album deeply rooted in the past—you can hear echoes of 1970s Motown, 1960s Stax, and even earlier jazz and blues in its grooves—yet it was also forward-looking, sowing seeds for future artists. Badu’s blend of Afrofuturist imagination (spiritual lore, astrological musings, a sense of gazing beyond the now) with everyday realism was relatively unprecedented; she crafted a persona situated in the current moment, yet conceptually unbound. This duality on Mama’s Gun—the warrior-priestess who can mourn police violence one moment and invoke African cosmology the next—helped pave the way for later genre-defying, socially conscious R&B auteurs. One can draw a line from Mama’s Gun’s fusion of the personal and political to albums like Jill Scott’s Who Is Jill Scott? (released the same year) and, further down the line, to the work of artists such as Janelle Monáe and Solange.

When Beyoncé (whom Badu affectionately nicknamed “Queen Yoncé” in a nod to her stature) released her celebrated Lemonade in 2016—a multimedia album lauded for its raw honesty about marriage, Black identity, and womanhood—critics were quick to note that Badu had already mapped out that blueprint over a decade earlier. Mama’s Gun, indeed, was a blueprint for how a Black woman in music could be unapologetically herself, weave social commentary into sultry jams, and prioritize authenticity over commercial formula. It’s an album that wears its heart and intellect on its sleeve. Badu posited that Black love, in all its forms—love of self, love of community, romantic love, ancestral love—is both a shield and a sword in a world of injustice. She asserted feminist self-care (“all you must hold on to is you”) and communal uplift in the same breath, showing that those aims aren’t contradictory but deeply intertwined. Whether it’s the sonic influence (the live-band aesthetic that can be heard in the musical DNA of groups like The Roots or in D’Angelo’s disciples) or the thematic influence (think of India.Arie’s self-love anthems, or the way today’s alt-R&B singers freely mix activism with sensuality), Mama’s Gun is a north star. The album’s very title hints at protection and offense in equal measure: the nurturing mother and the metaphorical weapon.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)