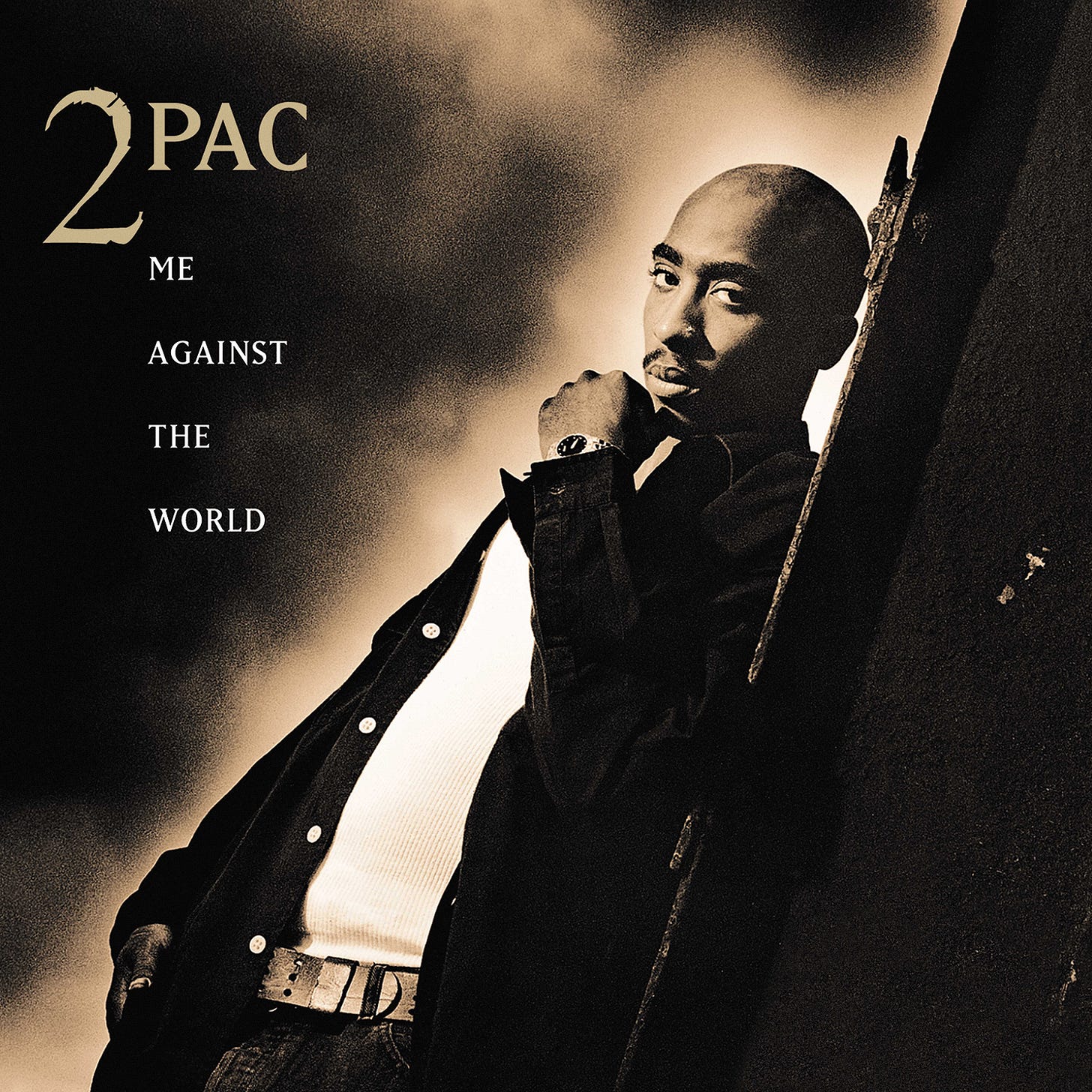

Milestones: Me Against the World by 2Pac

2Pac went all out on ‘Me Against the World’ to steer away from the orthodoxy he had tried to establish in his early years.

Although the structures of certain standout tracks venture into previously explored territory—one can doubt that a longtime fan, or even a neophyte more accustomed to the work of any number of MCs influenced by 2Pac (Master P, Freddie Gibbs, or even YG), would fall off their chair listening to “Young Niggaz” or “Outlaw”—2Pac went all out on Me Against the World to steer away from the orthodoxy he had tried to establish in his early years.

Bundled in his superstar persona, under scrutiny from the tabloids and puritanical leagues that transformed each misstep into a major scandal, he peppered his lyrics with various maxims (“Always do your best,” “Don’t let the pressure panic you”), rapped calmly, and made his words the absolute critics of a society plagued by widespread defects. In short, he was no longer a thug in resistance mode but rather one seeking redemption—obsessed with death. “If I Die 2Nite,” “Death Around the Corner,” and “Lord Knows” all border on the suicidal:

“I smoke a blunt to take the pain out/‘Cause if I wasn’t high, I’d probably try to blow my brains out”; “I’m hopeless/They should’ve killed me as a baby / Now they got me trapped in the storm /I’m goin’ crazy.”

Such admissions of vulnerability were almost unheard of in gangsta rap, where only Gravediggaz’s “1-800 Suicide,” released in 1994, had dared to write lyrics drenched in despair.

Originally, the album was going to be called Crucify, which explains the presence of these nighttime visions, contradictory emotions, and personal remorse. “All around me, I feel suicidal. But I can’t kill myself. I just wish someone would do it for me,” he confided a few weeks before recording. That’s why only “Young Niggaz” carries any hope, while other tracks reveal a nihilistic view of the world (“Fuck the World”), a profound analysis of gangster life (“Heavy In the Game”), a nostalgic tribute to hip-hop’s early years (“Old School”), or a grim forecast of the future (“It Ain’t Easy,” “So Many Tears”):

“Today I’m lost and weary, so many tears/I’m suicidal, so don’t stand near me/ Every move is a calculated step to bring me closer/To embrace an early death, now there’s nothin’ left.”

Fueled by this dark outlook—a tense mood that keeps him from smiling and narrates a tragedy—and bolstered by a variety of samples (“Walk On By” by Isaac Hayes, “Computer Love” by Zapp, “My Adidas” by Run-D.M.C.) and production work finally on par with the lyrics (producers like Tony Pizarro, Shock G, and Easy Mo Bee—known at the time for his collaborations with Biggie—each bring their own touch), Me Against the World was certified double platinum on December 6, 1995 (two million copies sold, then three and a half million by September 2011) and became the first album by an incarcerated artist to reach No. 1 on the American Billboard charts. Even more impressive, the record was honored as Best Rap Album of 1996 by the Soul Train Music Awards and nominated for Best Rap Album at the 1996 Grammys—although the award ultimately went to Poverty’s Paradise by Naughty by Nature.

If Me Against the World was his biggest success thus far—with three and a half stars in Rolling Stone (“an album of pain, anger, and burning desperation”) and four stars in The Source—it was produced using the same methods as before. In the studio, he was constantly chain-smoking joints and knocking back cognac. That had become the engine of his creativity, as well as a way to escape and relieve stress. “He wasn’t that happy; a lot of his laughter sounded fake,” Shock G, who was involved in the production, later lamented. As for Easy Mo Bee—perhaps the most involved producer in the making of Me Against the World—he remembers his friend as an artist with “a very particular recording process” and expanded on 2Pac’s methods in interviews:

“When he started recording, he never wanted to stop, and he didn’t like doing multiple takes. In other words, a song typically has three verses. And Tupac…would ask you to run the tape for the entire track. ‘Don’t stop it, don’t rush me,’ he’d say. Some people do one verse, then stop, then start on the second verse. Pac didn’t like stopping… He’d do everything in one take. If there’s something I learned from him during those sessions, it’s that you don’t need to be perfect. Just be yourself and pour your heart and soul into it…”

Despite the success of Me Against the World, 2Pac avoided flaunting it. He felt he was at his peak, at least artistically, but he had learned to keep a low profile.

“In prison, you see things differently. Nothing really matters. You can’t take everything so seriously because you’re dealing with killers. If they talk down to you, you can’t be like, ‘What did you say?’ You have to say, ‘Okay, if you don’t mind…?’ You learn to keep everything in check.”

Speaking with an impressive flow of consciousness rather than any pompous academic style, he admitted suffering from a sort of schizophrenia. He claimed he had two Black men inside him. One wanted to live in peace; the other couldn’t accept dying without finding freedom:

“My mother and the Black Panthers dreamed of a better world for us and fought for that. I was raised with those ideals. But in my everyday life, I see that this world is out of reach. It only exists in our minds. We can dream about it on Christmas Day…”

He also said he wanted “to dig deeper into his music.” So he decided to gather his people—all the rappers who had backed and supported him in recent months. He kept in touch with Big Syke and his half-brother Mopreme but also brought on board members of an Atlanta-based group called Dramacydal, who had already joined him on the B-side to “Holler If Ya Hear Me,” “Flex.” The goal was to form the Outlaw Immortalz. “Immortal outlaws”? Not exactly. Once again, 2Pac turned definitions on their head, using the word “outlaw” as an acronym for “Operating Under Thug Laws As Warriorz.”

Big Syke explains:

“We got together to decide on a name, and I suggested ‘Boss Playa.’ Pac was like, ‘Naaah,’ and started reeling off the different nicknames we’d come up with. So, the next day, we go to see him again, and he says, ‘We’re gonna be the Outlaw Immortalz.’ I didn’t really get what ‘immortal’ meant at the time, but Pac was always throwing out words that made us run to the dictionary.”

In the visiting room at Dannemora prison, Tupac sat with the Outlawz and gave each of them a personal nickname, all inspired by the names of dictators and heads of state. For him, it was a way to strengthen his mythology and secure the group’s legacy. As Big Syke notes:

“If you look at those names, whether they were good or bad, they changed the world, they broke down barriers. It wasn’t just about music. For Pac, it went deeper than that; it was about immortalizing the moment we’d blow everyone away.”

Hence, Big Syke became Mussolini, Mopreme became Komani, Yafeu Fula became Yaki Kadafi, Bruce Edward Washington became Hussein Fatal, Mutah Beale became Napoleon, and Malcolm Greenidge was renamed E.D.I. Mean and K-Dog took the name Kastro.

“He renamed everyone,” Big Syke recalls with a barely concealed smile. “I didn’t know who that fucking Mussolini was, so I had to read up on the guy. Pac made me want to read.”

Napoleon, whom Tupac saw as his protégé, also acknowledges his mentor’s importance in his life. Orphaned at three after seeing his parents gunned down before his eyes, he saw in the creator of Me Against the World the big brother he needed to succeed:

“The first time I recorded, I was sixteen. When I first met this brother, I had moved to Atlanta and joined this group called Young Thugz, which later became Dramacydal, with Kadafi, E.D.I., Kastro, and me. One of the first songs he put me on was ‘Me Against the World.’ I was just a teen back then, but I wasn’t living like a normal teen. With Pac by my side, I had to grow up. He wanted us to grow up and stay focused—simply because he poured his heart and soul into his music. Half of the Outlawz are related to him. So I remember Pac introducing us, saying, ‘Here’s my cousin Edi, my cousin Kastro, my brother Kadafi, here’s my man Fatal, he’s the lieutenant, here’s my man Mussolini, Noble, and here’s my protégé Napoleon.’”

As he had done a year earlier with Thug Life, 2Pac saw supporting the Outlawz as a way to highlight rappers who had never been in the limelight, never appeared on TV shows, or graced the covers of hip-hop magazines. It was also his way of letting the American public know that he was thinking beyond his own experiences:

“I took under my wing a group addressing the issues that a younger generation is going to face. They incorporate these problems into their rhymes, almost like turning a psychology session into music.”

The only issue: the Outlawz members were never outstanding lyricists, top-notch technicians, or impressive freestylers. Their inclusion in hip-hop encyclopedias is more about their connection to Tupac than their own inherent skills. According to Big Syke, he and his bandmates were also far from the most disciplined artists:

“The thing about Pac is that when it was time to hit the studio, he never let us bring groupies. He was smart. He wasn’t gonna fall for that groupie game; only his people could be there.”

Like young students in search of life lessons, the Outlawz learned to stay focused, refine their lyrics, and work relentlessly seven days a week. In a voice that suddenly takes on a nostalgic tone, Big Syke recalls:

“We might have been exhausted, going from studio to video shoot nonstop, but if we wanted to sleep, he’d either curse us out or threaten to send us home. He controlled us with military-style methods. […] We messed up hundreds of times, and I still wonder what drove him to be so patient with us. He was always by our side; he was a great teacher. He taught me plenty of things, but especially to talk about what’s going on in the world, not just follow popular trends. He told us that sooner or later, our music would become popular because it would talk about things people could relate to.”

From the very first minutes of Still I Rise—the fruits of their collaborative efforts, released in 1999—you can sense the emergence of a fired-up collective on “Letter to the President,” which criticizes Clinton’s contempt toward the Black community:

“They claim that bein’ high got me fiendin’/But America is messed up and cursed/I figure it’s ’cause we Black that we targets/My only fear is God, and damn I ain’t scared to say it/In case you don’t know, I give a holla out to my niggas/I’m fightin’ for Mutulu like I’m fightin’ for Geronimo/I’m ready to die for all the causes I believe in/So for every word in this letter to the President…”

True to form, 2Pac also delivers other socially charged tracks here—“Teardrops and Closed Caskets” explores ghetto realities, while “The Good Die Young” proves the Outlawz kept working on this album well after 2Pac’s death because its final words are dedicated to the victims of Columbine—yet Still I Rise ultimately raises more questions than it answers. After all, can an album help bring about a new world without rethinking the very possibility of a new sound? Not that this record advocates a drastically reformist social agenda through an inherently conservative hip-hop filter, but it must be acknowledged that Still I Rise was produced with a formulaic approach that can become tiresome on certain tracks.

“Homeboyz” or “Killuminati” refuse to go against the grain and, in the end, add nothing particularly new to 2Pac’s body of work, while “Baby Don’t Cry (Keep Ya Head Up II)” is appealing but lacks the impact of the 1993 version. Even so, Still I Rise is exciting—likely thanks to the cornerstones of 2Pac’s art: linguistic mastery, the depth of his words, and a consistent worldview bursting with power and scope. Also, starting in 1995, there was a clear willingness to lean on G-funk beats and to encourage blending rap with the most melodic side of R&B, including sung hooks and swooning female choruses. Juxtaposing tracks like “Black Jesuz” and “Hell 4 a Hustler” shows that 2Pac still found himself halfway between good and evil, between raw brutality and idealism—just as “Secretz of War” features a melody and mass appeal fit for MTV while staying grounded in the raw essence of rap.

When Me Against the World was released on March 14, 1995, Tupac had already been in prison for several weeks. After the trial, the court granted him two and a half months of recovery time—first at Metropolitan Hospital, then at Jasmine Guy’s home. Ultimately, however, he ended up in the monotony of a drab cell, trying to pass the days however he could. Everyone was telling him he’d never rap again. If he answered back, he was immediately sent back to his cell. And yet, Tupac had reasons to boast: Me Against the World debuted at number one on the sales charts, moving 240,000 copies in barely a week. In the second week, sales continued to climb. So did they during the following three. The album was a genuine hit. Tupac was understandably overjoyed:

“I was getting Entertainment Weekly to see the rankings. It tripped me out to be number one in the country.”

Two months earlier, Vibe had sensed an opportunity. The article would only appear in the April issue, a few weeks after Me Against the World hit the shelves, but the editor-in-chief was firm on the matter: they had to land an interview with the rapper. If they pulled it off, it would be his first interview since November 30 of the previous year. Luck was on their side: Tupac wanted to speak and requested that a journalist come see him.

On a cold January day, Kevin Powell arrived at Rikers Island prison. After passing a series of checkpoints and metal detectors, the journalist found himself in a plain white conference room. Tupac came in shortly afterward, wearing a white Adidas sweatshirt and oversized jeans, no longer limping, and seemingly open to conversation. Kevin Powell was not surprised by his cooperative attitude. However, what shocked him was Tupac’s nervousness and the compulsive way he chain-smoked Newport cigarettes. And also his first words:

“This is my last interview. If I get killed, I want people to know my real story.”

From that moment, Tupac let everything spill out, never worrying about the possible consequences. He said he was constantly being insulted in prison, regretted having more responsibilities than anyone else his age, saw his incarceration as “God’s will,” admitted he had been “addicted to weed,” and spoke of how Black people can sometimes betray each other. To illustrate this, he cited Malcolm X—murdered by “his own”—and directly pointed the finger at Bad Boys Records. Behind all these accusations, Tupac seemed primarily to be questioning himself. He knew that clubs, weed, alcohol, and women were all normal temptations for someone his age, yet he now prayed that God would “let him live long enough to accomplish something extraordinary.”

In prison, Tupac had apparently stopped smoking weed, quit coffee and red meat, taken up yoga, practiced various martial arts, and studied meditation. On April 29, in front of his mother and cousin, he even married Keisha Morris, a young woman he had met at the Chippendale’s Club in June 1994. Their relationship was still fairly new, but they were sure of their love. For her birthday on November 10, 1994, Tupac bought her a BMW 735 and a Gucci watch. To everyone around him, Tupac appeared serene. But that feeling did not last. When Kevin Powell interviewed him again in December 1995, Tupac had signed with Death Row, ended his marriage, and was playing a dangerous game that worried those closest to him:

“The first week of December 1995 was the last time I spoke to him. I really believed, based on our prison conversations, that he was going to change. He talked differently about women and about racial issues. But when I interviewed him on a video set, there was marijuana smoke coming out of his trailer, and he was flashing his money. I took it personally. I was thinking, ‘My God, this dude is never going to change.’ It depressed me. I knew it was the last time I wanted to interview him. I didn’t know he was going to die; I just knew it was the last time. I remember wishing he was still in prison. He would have been protected from the people who wanted to kill him physically—and also spiritually.”

Rating: Masterpiece (★★★★★)