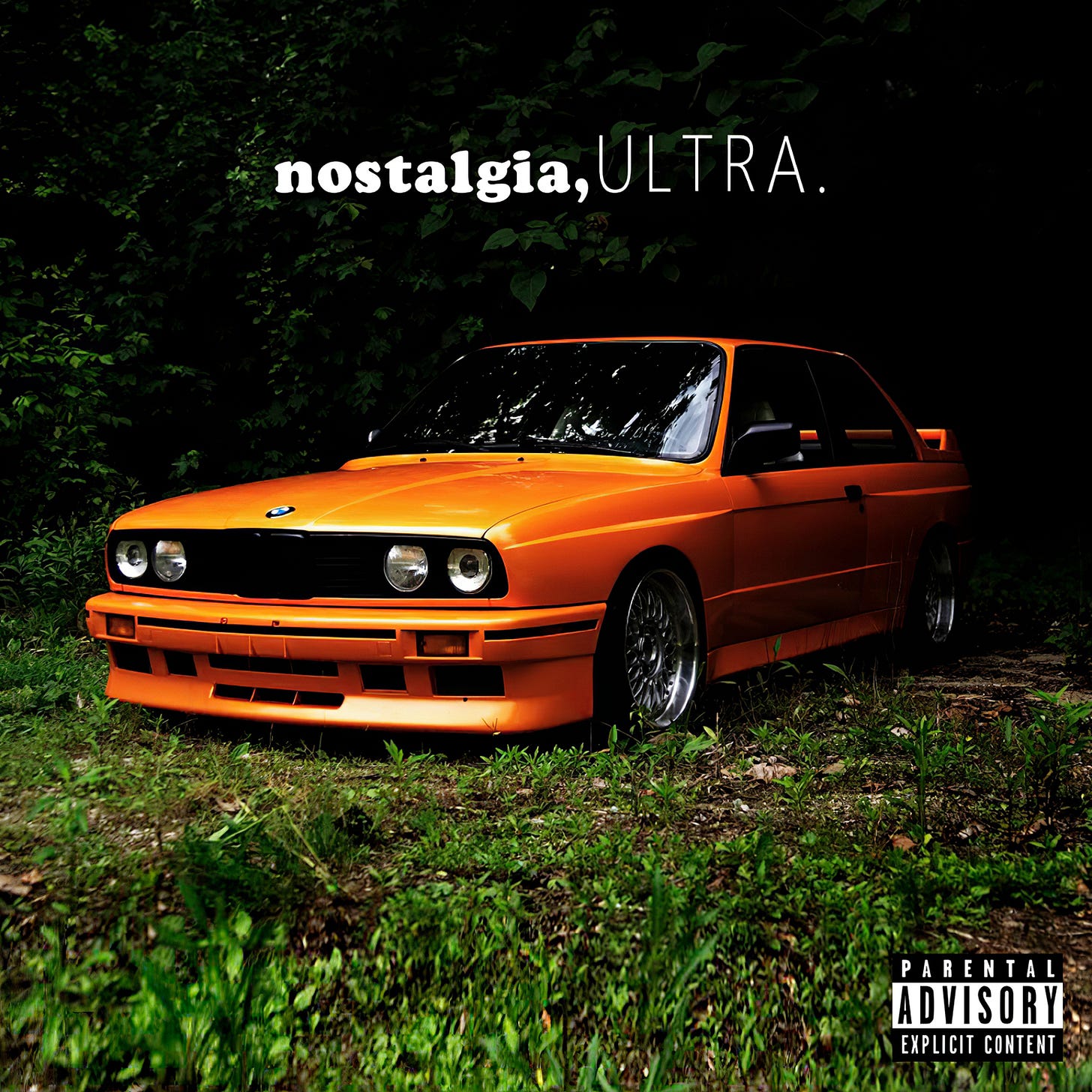

Milestones: nostalgia,ULTRA. by Frank Ocean

On his 2011 debut mixtape, a twenty-three-year-old Ocean kept reaching for anesthesia, performance, and cinema to dodge a fear he never quite named.

Before anybody knew his voice, they knew his penmanship. Christopher Breaux ghostwrote for John Legend on “Quickly” and handed Brandy “1st & Love,” competent songs that dissolved into their respective albums without clinging to his name. He signed to Def Jam through Tricky Stewart’s RedZone imprint around 2009, and for months, the label did almost nothing with him. The deal stalled. Breaux drifted toward Odd Future, the loose-cannon hip-hop collective fronted by Tyler, the Creator, who were lighting small fires across the internet with shock-value rap and a complete disinterest in industry protocol. In the summer of 2010, Ciara introduced a quiet guy named Lonny Breaux on her Ustream broadcast—they’d been cutting songs together in Stewart’s studio, and she’d been playing his demos for anyone who’d listen. He was already someone else by then, or becoming someone else. With no warning to his label, no rollout, no single, a person now calling himself Frank Ocean posted a link on his Tumblr blog, tagged the genre as “bluegrass,” and gave away everything he’d been holding.

The project that landed, nostalgia,ULTRA., did not behave like a mixtape. Most R&B mixtapes at that moment were promotional throwaways, loosies grafted onto rap beats, clearance-bin auditions. This one arrived sequenced, with interludes modeled after cassette-deck sounds and video game references—Street Fighter, GoldenEye 007—that dated themselves to the late ‘80s and ‘90s on purpose. The original material came from producers with hitmaking resumes. Stewart handled “Novacane.” MIDI Mafia, Happy Perez, and James Fauntleroy II split duties elsewhere. But the care went past the credits. Ocean alternated between his own compositions and re-voicings of existing songs—Coldplay’s “Strawberry Swing,” Mr. Hudson’s “There Will Be Tears,” the Eagles’ “Hotel California,” MGMT’s “Electric Feel”—and fitted the borrowed material flush beside the originals without announcing its borrowed-ness. The effect was a man building a room that happened to contain furniture from different houses, all of it rearranged until it looked chosen, not scavenged.

Those covers and rewrites were not random. Singing over Coldplay is a different bet than singing over a Trey Songz instrumental—it refuses the audience’s expectation of where an R&B singer belongs and tells them to recalibrate without asking permission. Rewriting “Hotel California” as a story about a throwaway marriage that disintegrates before the reception champagne goes flat aimed the Eagles’ overplayed grandiosity at something small and self-lacerating. Draping an MGMT sample under a sex song tilted the pleasure toward psychedelia. None of these choices telegraphed taste or eclecticism for their own sake. They each repointed a familiar melody toward Ocean’s emotional concerns—loss that hasn’t finished happening, desire that curdles midway through the act, loneliness wearing someone else’s clothes. He sang these songs as if they’d always been his problem set, and the casualness of the theft made the theft disappear.

What separated him from every writer he’d ghostwritten for, and from the crowd of crooners working the same Def Jam corridor, had nothing to do with his beat selection or his name-dropping. His distinction sat in his wistful, self-effacing perspective and his numbed, restrained delivery. The voice itself was not gymnastic. He did not oversing. He held back on runs, sat behind the beat rather than ahead of it, and phrased with a flatness that mimicked exhaustion or medication or both. That flatness was a method. When the writing turned confessional, the lack of adornment forced the words to carry whatever weight the song had. There was no melisma to hide behind, no belted climax to distract from what he was actually admitting. Each line arrived sounding less like performance than dictation, someone reporting on himself in real time, slightly embarrassed that you’re hearing it.

“Songs for Women” is where the method opens up widest. Ocean begins the song questioning whether he sings to sing or sings because women respond to it. He admits he can’t play guitar like Van Halen, admits he has no hidden chords. Then the scene sharpens. After school, in his dad’s empty house, because his dad doesn’t clock off until late. He and a girl flip through his vinyl collection. She teaches him to slow dance. He gives her chills harmonizing to Otis Redding, the Isley Brothers, Marvin Gaye. The name-checks are trophies he’s mounting for a girl, showing off the only currency he owns. The brag doubles as seduction, and the seduction doubles as something sadder: a kid trying to prove his worth through borrowed greatness, alone in a house that belongs to a father who isn’t around. When the song tips forward in time and the girl stops visiting, stops listening to his recordings, starts playing Drake in his car, the complaint wraps back around into self-implication. He sang to get at women. He said so. The strategy worked until it didn’t, and the failure was baked into the honesty from the first bar. The whole song hinges on the gap between two versions of the same confession.

Ocean salted the tape with Stanley Kubrick. He dropped the name casually in “Novacane,” calling himself visionary while filming pleasure with his eyes wide shut, and later, on a separate song, sampled actual dialogue from Eyes Wide Shut. The two references land far enough apart that they register as a recurring habit rather than a gimmick. Kubrick is a useful prop for him. The director’s films are cold, meticulous, and fixated on people losing control inside controlled environments. Ocean borrowed that temperature for his own material, ornamenting loneliness with a reference that said he’d thought about his loneliness rather than merely suffered it. The cinema was a second layer of self-consciousness on top of an already self-conscious vocalist, and it worsened the loneliness, because intelligence doesn’t cure anything. It just annotates the wound.

For a twenty-three-year-old, Ocean spent a suspicious amount of the mixtape staring into his rearview. The backward gaze was everywhere, from the title down through the cassette-deck interludes and the decades-old rock samples he repurposed as confessionals. But nostalgia on nostalgia,ULTRA. wasn’t warmth or comfort. It surfaced as hesitation, the pause before committing to a feeling, the instinct to measure a present-tense experience against something already finished. His narrators daydreamed about old bedrooms, old records, old girls. They flinched at right now. Desire arrived already tinted with aftermath, as if he’d trained himself to grieve pleasures before they ended. That reflex aged the tape past its maker, and it gave the love songs a particular claustrophobia. The past kept crowding into the present, and the present never got enough oxygen to develop on its own terms.

The claustrophobia turned physical on a shore drive. A Lincoln Town Car with a trunk big enough for broken hearts, the trunk “bleeding” as Ocean cruised the boulevard. Black suit on. Headed somewhere that looked like a funeral. Then the destination arrived on “Swim Good.” Driving into the ocean, trying to swim from something bigger than himself. The self-destruction was plain, and he lit it with a punchline, the Patrick Swayze ghost joke, that deflated the gravity without erasing it. The Swayze line didn’t soften the image of a man steering his car into the water. It proved that Ocean could hold two tones at once, the comedic and the annihilating, without one canceling the other. The humor was a survival mechanism, and the song knew it wasn’t working.

How real was any of this? Two songs near the tape’s end pulled the question in opposite directions. “Nature Feels” staged a Garden of Eden fantasy, frank about sex, unbothered by shame, and mounted it on MGMT’s “Electric Feel,” whose warped synthesizer swirl dragged the biblical toward the hallucinatory. The borrowed production did specific work. It turned the temptation narcotic, less like a decision than a drift, and the pleasure arrived unstable, half-convincing, as if the Eden were someone’s fever and not a place. “Novacane” pulled in the opposite direction and wound up somewhere adjacent. A dental student moonlighting in pornography, cocaine for breakfast, a tripod with a red light on, Kubrick surfacing again. Ocean crooned about chasing a feeling he’d already lost, numbing the loss with the same anesthetic the girl dispensed, and the song played both drugged-out and hyperaware, conquest-heavy and desperately lonely, all inside a Tricky Stewart beat so sparse it almost evaporated. When the production dropped away entirely and a distorted voice seized the track, the dissociation stopped being a subject and became a formal property of the song itself. “Novacane” was the most unreal thing on the mixtape and, because it refused to prettify its confusion, maybe the most grounded.

The mixtape mattered as an arrival because of what it refused. Ocean did not shop a single to radio. He did not run a campaign. He did not wait for clearance from the label that had shelved him. He typed a Tumblr URL, tagged it incorrectly, and disappeared from the frame. The construction did the rest: the careful sequencing, the re-sung rock songs presented as private letters rather than cover-band flexes, the self-aware voice that kept sabotaging its own seductions. People passed the link because the tape sounded finished, and because Ocean’s willingness to give it away for free scrambled the usual arithmetic of how a new vocalist accumulated attention. The beats were not the reason it spread—they were functional, content to stay out of his way. The attention gathered around his writing, his perspective, and the strange intimacy of hearing a stranger confess things he seemed to half-regret confessing.

The productions deserve their honest accounting. They are serviceable: crisp enough, professional enough, occasionally inert. No beat on nostalgia,ULTRA. sounds especially left of center, and none pushes the sonic frame past competence into personality. On weaker stretches, the instrumentals sit where a sharper ear would have injected tension or friction, and Ocean glides over them the way a driver steers through flat highway, safely, distantly, with the scenery doing little to sharpen the trip. What keeps the mixtape from sagging under that blandness is his phrasing. He timed syllables against the beat in ways that created suspense where the production offered none. He bent lines at odd intervals, paused where a lesser voice would have filled, and treated silence as a rhythmic instrument. The gap between what the beats gave him and what his delivery extracted from them is, in many stretches, the entire show.

He kept reaching for things to put between himself and the fear. Anesthesia, literally, in the form of Novacane. Performance, crooning for women because the crooning worked, until it didn’t. Nostalgia, looking backward because the past can’t hurt you a second time, except it can. Reference—Kubrick, Swayze, Otis, the Eagles—other people’s language used as furniture for an interior he couldn’t decorate with his own. None of it sealed. The fear sat under every song, patient and un-narrated, waiting for the jokes to stop, the samples to end, the girl to leave, the car to reach the water. Ocean knew it was there. He never named it. The mixtape was built around that evasion, and the evasion was the most honest thing on it. A man making beautiful, elaborate moves to avoid saying the plain, small thing he was afraid of, and every move confirming its presence by the size of the distance it tried to open.

Great (★★★★☆)