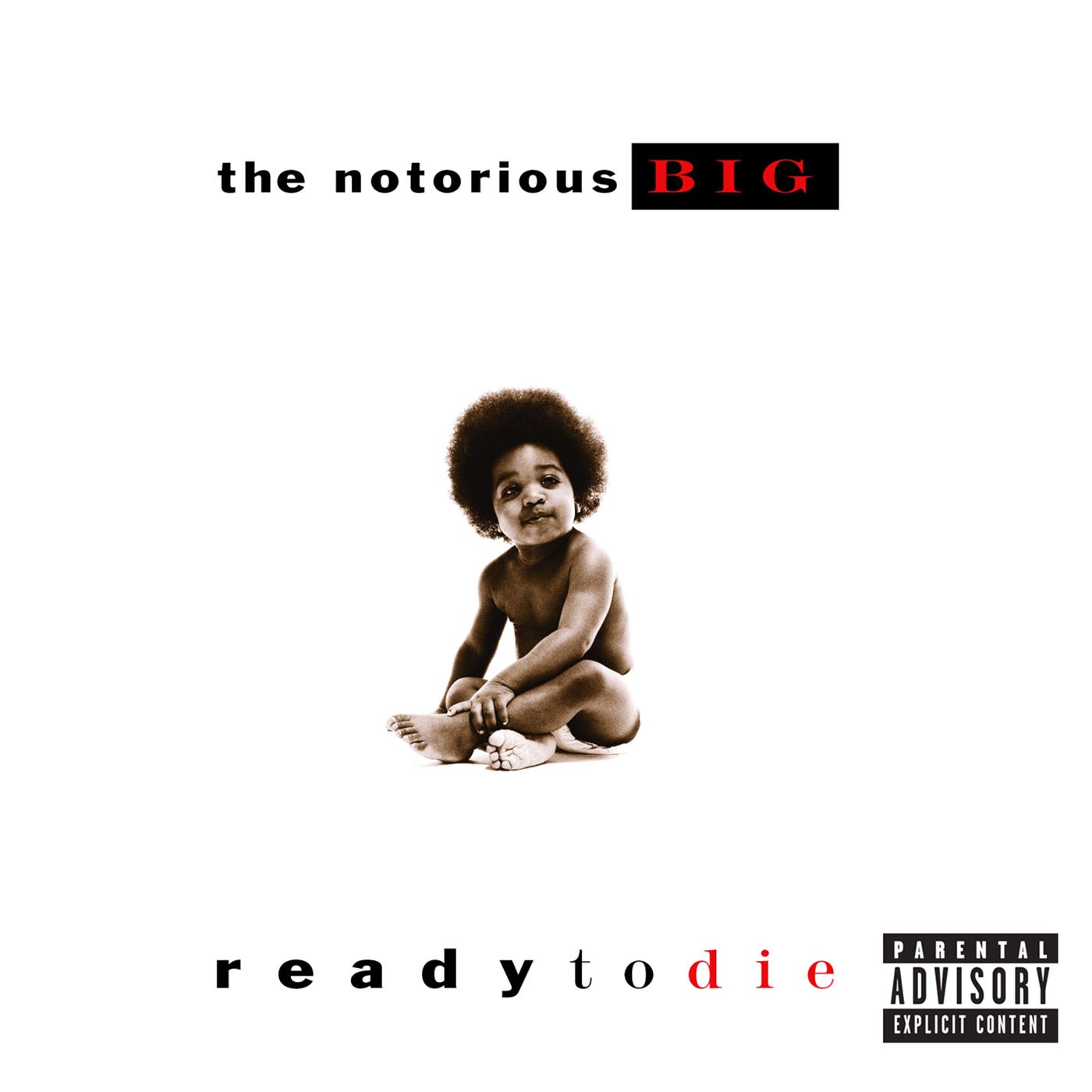

Milestones: Ready to Die by The Notorious B.I.G.

"And if you don't know, now you know.” With Biggie’s debut, not only it’s an unprecedented art in hip-hop history, but it birthed a commercial rap formula that’s still being followed to this day.

The hip-hop landscape was forever altered on September 13, 1994, when Ready to Die hit the shelves. Though it initially claimed a modest 15th spot on the charts, this groundbreaking album clung tenaciously to the hit lists for an impressive 60 weeks, eventually achieving multi-platinum status. It stands as the East Coast’s first truly lucrative rap record, marking a focal shift in the genre’s geographic dominance.

At the heart of this success lies an unprecedented fusion: a record that bridges the chasm between the harsh realities of New York’s underprivileged neighborhoods and the glitzy, often shallow world of entertainment. The album’s genius lies in its ability to be uncompromising yet radio-friendly, cinematic yet authentic, and hard-hitting yet memorable. It speaks to both the streets and the masses, a feat that seemed nearly impossible at the time.

The mastermind behind this cultural phenomenon was none other than Sean Combs, then known as Puff Daddy (The Diddler person got whole other problems going on right now). His newly established label, Bad Boy Records, rocketed to prominence on the back of Ready to Die. Combs’ innate understanding of the zeitgeist, coupled with his adept handling of a powerhouse like Biggie Smalls, proved to be a winning formula.

“I got big plans, nigga. Big plans.”

With these words and a self-assured chuckle, The Notorious B.I.G. kicks off his debut, diving headfirst into a world of violence tempered by his signature charm and wit. The confidence in his delivery suggests he already knew Ready to Die was destined for legendary status.

The album’s triumph can be attributed to the unbeatable pairing of Puffy’s commercial instincts and Biggie’s raw talent. Crucially, it was Biggie’s willingness to embrace his mentor’s vision that set the stage for their success. This mutual trust formed the bedrock upon which the debut LP was built. By reclaiming the spotlight for the East Coast, Ready to Die effectively ended the West Coast’s reign over the rap scene. It ushered in a new era of gangster rap in the very place where hip-hop was born, forever changing the landscape of the genre.

The journey from obscurity to stardom is a tale as old as time, yet Ready to Die narrates this quintessential American saga with unprecedented authenticity. The album’s power lies in its ability to embrace contradictions, presenting a multifaceted narrative that spans from destitution to opulence, from illicit substances to carnal pleasures.

Sean Combs, then an A&R at Uptown Records, stumbled upon a demo tape of an aspiring rapper. Despite The Notorious B.I.G.’s unconventional appearance and lack of experience, Combs envisioned not just a successful artist, but a sex symbol. This audacious gamble would prove to be a watershed moment in hip-hop history.

Initially, Biggie and Combs focused on crafting grittier, more visceral tracks like Ready to Die, “Gimme the Loot,” and “Things Done Changed.” These compositions resonated with the harsh realities of urban life, reflecting Biggie’s firsthand experiences in the criminal underworld. His vivid depictions of street life in tracks such as “Gimme the Loot” and “Warning” stem from his intimate knowledge of that environment.

The album’s dual nature—showcasing both the grim realities of street life and the glitz of success—is a product of its tumultuous creation. When Combs unexpectedly lost his position at Uptown Records, Biggie’s musical aspirations were suddenly jeopardized. Faced with uncertainty, the rapper briefly returned to his former illicit activities.

However, setbacks only fueled Combs’ determination. He established his label, becoming his boss and bringing his protégé back into the fold. During this period, Biggie honed his craft, no longer relying on written lyrics for his recordings.

“Things Done Changed” captures Biggie’s fervent desire to trade his life of crime for an entertainment career:

“If I wasn’t in the rap game, I’d probably have a key knee-deep in the crack game.”

This sentiment underscores the album’s narrative of transformation and ambition.

Ready to Die thrives on its contrasts rather than being torn apart by them. It paints a complex picture of life, death, struggle, and triumph, offering a raw yet nuanced portrayal of the American Dream. From poverty to prosperity, from despair to hope, the album tells a story that is as multifaceted as it is compelling.

The creation of Ready to Die was marked by extraordinary talent and unexpected collaborations. Easy Mo Bee, who produced many of the album’s tracks under Puffy’s guidance, found himself creating hardcore beats he hadn’t encountered before. “I actually didn’t work with anyone who used such hard vocabulary,” he confessed. “When I was in the studio, I was always the one who said, ‘Man, are you really sure you can put it that way?’ I kept hearing only: ‘Mo, relax’ you. You Sensitive!’ I was only worried because I finally wanted the record to be sold.”

One of Easy Mo Bee’s notable contributions was “Gimme the Loot,” a track that ingeniously sampled James Brown, Onyx, Ice Cube, Gang Starr, and A Tribe Called Quest. The song’s narrative follows two individuals planning a heist. “People are still asking me who the second rapper is. ‘Yo, who was that? Was that the puff?’ The fact that no one hears that Biggie has rapped in both voices only shows how good he was,” Easy Mo Bee remarked.

As the album neared completion, DJ Premier was brought in at the eleventh hour to produce “Unbelievable,” the final track for Ready to Die. Premier recounted to Complex magazine, “I almost wasn’t there. Big called me at the last minute and asked: ‘Give me a track!’, and I told him that I don’t have time at all to make one.” Despite Premier’s usual rates being much higher, Biggie’s limited budget of $5,000 and their friendship led to a compromise. Surprisingly, Biggie was present during the beat-making process, even suggesting the use of the Nasty Piper’s “Your Body’s Callin’” as a sample—a choice that proved brilliant.

By this point, Biggie’s freestyle abilities had reached astonishing levels. DJ Premier observed, “He sat there for hours, and you thought he didn’t do anything. He’s not even concentrating. Then it’s three or four in the morning, and you ask: ‘Hey, do we want to record this today, or do we finish it tomorrow?’, and he says, ‘Nah, I’m ready.’ And then he gets up, goes into the booth. Get it out. Done.”

This extraordinary talent was evident throughout the recording process. DJ Premier recalled, “I never saw him jot down a single word. He always made a big show of needing a pen and paper, but then he’d create magic! At most, he’d sketch a few odd doodles.”

The raw, unfiltered nature of some tracks raised concerns. Easy Mo Bee admitted, “I was apprehensive because I truly wanted the record to succeed.” However, these edgier numbers had been recorded long before “Unbelievable” came to fruition, showcasing the album’s evolution and the diverse influences that shaped its sound.

The evolution of this album showcases the remarkable chemistry between Biggie and Puff Daddy. As the album neared completion, Puff recognized the need for radio-friendly hits to complement the gritty street tracks. “Okay, so far we’ve done what you wanted. Let’s do what I want now,” Puff declared. Rather than resisting, Biggie responded with pragmatism: “Puff says: Do it that way. So I’ll do it. Anyway, I’m trying.”

This willingness to set aside his artistic ego and embrace guidance was crucial, according to Lord Finesse. “That gave the whole thing the last kick,” he observed. “That he could put his artist ego aside and also accept advice once.” The result? Tracks like “Juicy”—admittedly saccharine, yet undeniably iconic. Sampling Mtume’s “Juicy Fruit,” became hip-hop’s first mainstream hit and set the template for rap tracks with R&B hooks.

Lord Finesse, who produced the album’s haunting finale “Suicidal Thoughts,” reflected on Biggie’s transformation: “When I first worked with Big, he was as street as you can be… But he and Puff have both evolved at incredible speed. Watching them both learned and how Biggie everything that Puff told him, like a sponge absorbed, that was crazy!”

He continued, “Puffy delivered the template, Biggie picked up the ball and sank it. The combination was simply incomprehensible… Puffy had it on to shape Big—not only as an underground artist, he rounded him off. He showed him not only how to throw baskets, but also how to dribble and all sorts of other tricks that made him the best player on the court. And Biggie learned really, really quickly.”

Biggie’s comedic talent and acting abilities shine throughout the album. Take “Warning,” for instance, or the awkwardly explicit “#!*@ Me (Interlude)” with Lil’ Kim, which reportedly left the piano stool worse for wear. Chucky Thompson recalled, “We had much crazier recordings than this one. But they were completely useless because we all laughed our asses off.”

Method Man, the album’s sole featured artist on “The What,” fondly remembered Biggie: “We always got along. He was a hilarious guy, kept you laughing all day.” However, not all of Method Man’s Wu-Tang colleagues shared this sentiment. “It’s no secret: Rae and Ghost weren’t fans. They accused him of biting. But then again, Rae and Ghost hardly like anyone.”

The recording process was marked by full-bodied commitment and a willingness to follow Puff’s lead. Despite Biggie’s initial protests that Puff was trying to turn him into an opera diva, tracks like “Juicy” emerged. This blend of street credibility and pop sensibility would ultimately define Ready to Die and cement its place in hip-hop history.

The album’s structure, chronicling Biggie’s life from birth to his imagined demise, is foreshadowed in its introduction. As Easy Mo Bee recounts, “Puffy said he wants ‘Rapper’s Delight,’ Audio Two’s ‘Top Billin’,’ ‘Superfly’—records that represent the whole era.” This amalgamation not only reflected Biggie’s journey but also captured the essence of his time and environment.

Surprisingly, the inclusion of radio-friendly singles doesn’t detract from the album’s raw overall impression. Instead, these tracks showcase another dimension of an incredibly adaptable artist. Biggie’s greatest talent lies in his ability to convincingly deliver fictional narratives by interweaving elements of his biography. As he raps, “Shit, my mama got cancer in her breast/Don’t ask me why I’m motherfucking stressed, things done changed.” This seamless transition from exaggerated bravado to disarming honesty, from hardened hustler to vulnerable individual, is a hallmark of Biggie’s style.

The New York Times praised this balanced approach: “By also presenting the lowlands of this lifestyle, Ready to Die contains perhaps the most balanced, honest representation of the dealer exity that hip-hop has to offer.” This multifaceted representation is evident throughout the album, from Biggie’s bold declaration to his attempts to leave behind the “Everyday Struggle” and focus on his craft: “I’m doing rhymes now. Fuck crime now.”

Initially, this new path seems promising: “I went from negative to positive.” However, underlying doubts persist, culminating in the album’s jarring conclusion, “Suicidal Thoughts.” Nashiem Myrick, involved in the production, admits, “I never talked to Biggie about this song, but we all had our concerns about whether you could even include it on the album. He killed himself on this record. How are you supposed to get back there?”

These concerns about the album’s finality proved prescient in an unexpected way. Ready to Die would be the only album The Notorious B.I.G. released during his lifetime. On March 9, 1997, mere days before the scheduled release of his sophomore effort Life After Death, Christopher Wallace was fatally shot in Los Angeles. His murder, like that of his friend, colleague, and rival Tupac Shakur, remains unsolved to this day.

The album’s concept, blending gritty realism with commercial appeal, set a new standard in hip-hop. Easy Mo Bee’s introductory track encapsulates this, combining influences that span generations of music. From the outset, Biggie’s intent is clear. These words, tinged with self-assured laughter, launch listeners into a debut that balances violence with charm and wit, seemingly confident of its place in hip-hop history.

Standout (★★★★½)