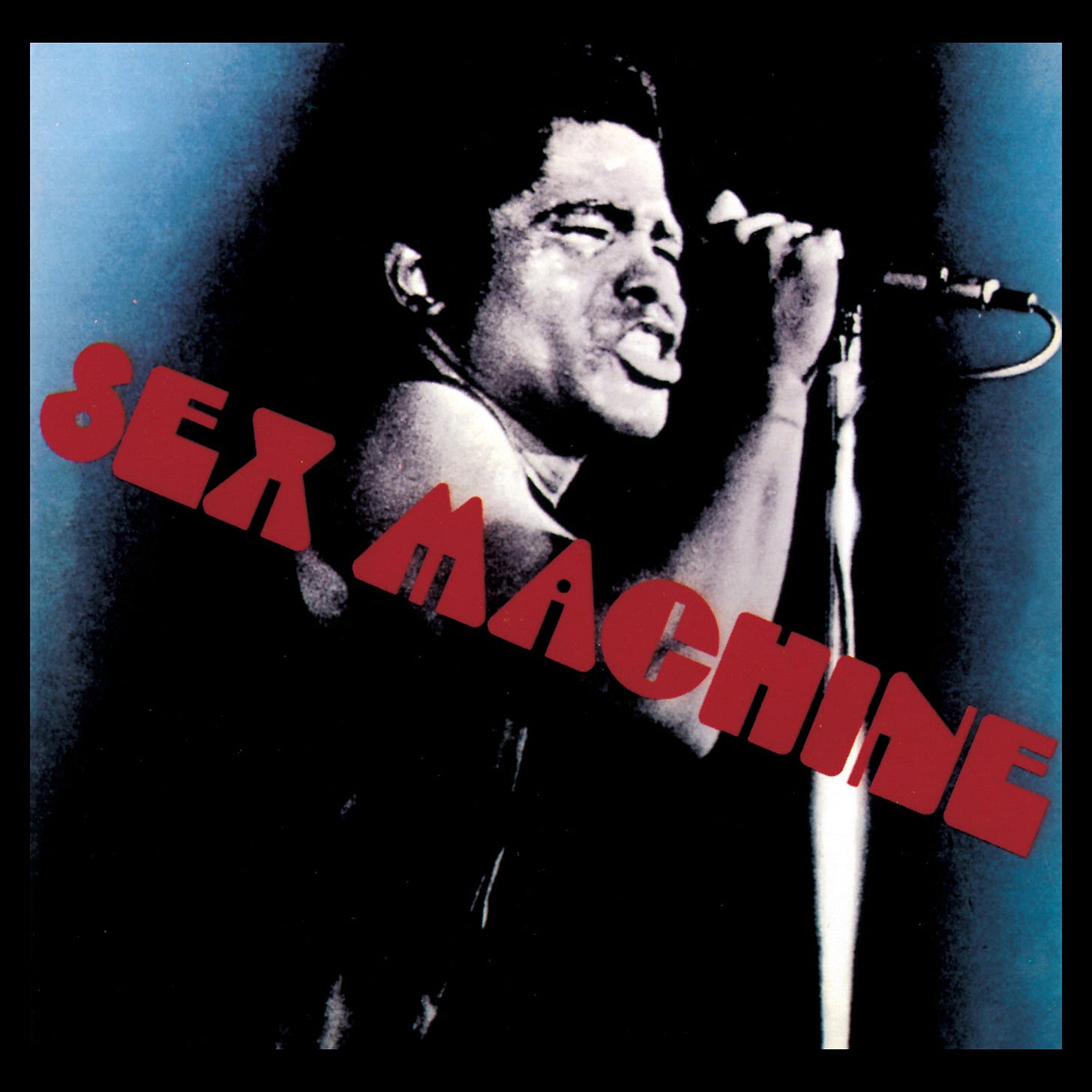

Milestones: Sex Machine by James Brown

The revolution he unleashed on that Apollo stage in 1970 still reverberates—a live document that remains a gold standard of funk, sending shivers down spines and making people get on up to this day.

Picture the legendary Apollo Theater in mid-1970—the air inside crackles with anticipation. On stage, James Brown’s newly forged band, the fiercest he ever assembled, is poised to strike. There’s Bootsy Collins on bass, barely 19 but already laying down a bass line as thick and funky as wet cement. His brother Catfish Collins stands on guitar, ready with a razor-sharp “chank” chord. At the drum kit is Clyde Stubblefield, the Funky Drummer himself, flanked by co-drummer John “Jabo” Starks—a two-headed rhythmic monster driving an unstoppable groove. In the horn section, Fred Wesley’s trombone and Maceo Parker’s alto sax wait to cut in with stabbing syncopation. And hovering by the organ is Bobby Byrd, Brown’s long-time right-hand man, primed to egg the crowd on with call-and-response shouts. The Godfather of Soul has reconvened his J.B.’s, a band of young guns with something to prove. After a tumultuous spring in which Brown’s old band walked out on him en masse, these upstarts from Cincinnati, the Collins brothers and their crew, answered the call overnight. They had zero rehearsal time, but they didn’t need it; like so many hungry Black bands of the day, they already knew James Brown’s repertoire inside out. Now they are The J.B.’s, and tonight is their trial by fire.

Suddenly, the announcer’s voice booms: “And now, it’s Star Time! James Brown!” The Apollo erupts in a roar. Brown strides onstage in a cape, soaking in the screams, then tosses the cape aside. “Fellas, I’m ready to get up and do my thing!” he shouts into the mic. “Yeah!” Bobby Byrd hollers back. “I want to get into it, you know, like a sex machine!” Brown declares. “Go ahead!” Byrd responds, stoking the crowd. “Can I count it off?” Brown asks. “One, two, three, four!”—and with that, the band detonates into “Get Up (I Feel Like Being a) Sex Machine.” What follows is nearly 11 minutes of pure, uncut funk that feels like a revolution happening in real time.

From its first downbeat, “Sex Machine” announces that James Brown has entered a bold new era. This isn’t the polished soul revue of his earlier Apollo recordings—it’s something rawer, nastier, and unpredictably funky. Bootsy Collins’s bass is the engine of the groove—busy, in-your-face, yet perfectly locked on the One (Brown’s signature emphasis on the first beat). He weaves a two-bar figure that bubbles around the guitar, climbing to octave jumps that hit you in the chest. “I threw a little bit of Jimi Hendrix’s style into the bass line,” Bootsy would later say, and you can feel that rock-inspired bravado in his playing. Jabo Starks holds a steady, no-frills drum pocket on this tune, while Clyde Stubblefield soon swaps in on the next numbers with his trademark kinetic groove—the same funky syncopation that would launch countless hip-hop breakbeats. Brown mostly plays ringmaster here: he’s on the mic and on the organ at times, but “Sex Machine” is about vibe over vocals. Compared to his 1960s hits, this track has minimal horns and lyrics—just a few key phrases like “Get on up! Stay on the scene, like a sex machine,” punctuating an extended instrumental workout. James and Bobby trade lines like live wires, Brown commanding “get up,” Byrd answering “Get on up!,” turning a simple refrain into a communal exhortation. The vocal interplay is as electric as the instrumental chemistry—two old friends urging each other (and the audience) higher.

The groove is relentless. When Brown feels like it, he cues a “bridge”—his famous command to shift the jam’s gears. “Take ’em to the bridge!” he shouts to Byrd, signaling Catfish Collins to snap into a faster, choppier guitar vamp around the two-minute mark. In James Brown’s world, a “bridge” isn’t a gentle song interlude; it’s a pressure release, a chance for the band to explode in a new direction before slamming back into the main groove. The genius of “Sex Machine” is that it barely resembles a conventional song—there’s no tidy verse-chorus structure, just a hypnotic rhythm that ebbs and flows with Brown’s calls. One critic put it this way: “It was so essential what he was doing. I don’t even know if you can call it songs… it was like a new form of music.” What Brown and the J.B.’s create on “Sex Machine” is groove as the dominant element—a blueprint for funk that would redefine popular music’s future. Close your eyes and you can see him on that Apollo stage: feet gliding in the James Brown shuffle, sweat flying as he spins and drops into splits, then popping up right on the One. The energy is so vivid it seems to leap from the speakers. Even though the original Sex Machine album was half recorded in the studio (with fake crowd noise added), Brown’s live intensity is palpable on every track. As a contemporary review noted, “James Brown’s live energy comes through on all of it. Close your eyes and you can see him spinning, dropping, and sliding across the stage.”

More than fifty years later, “Sex Machine” is widely hailed as one of the most important funk records. It marked the high point of Brown’s creative heyday (1967–1971), and a defining moment for this short-lived yet historic J.B.’s lineup. In early 1970, Brown’s veteran band (which had backed him on classics like “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” and “I Got You [I Feel Good]”) threatened mutiny over pay. The Godfather, ever the taskmaster, wasn’t about to be held hostage—he famously fined and disciplined his musicians onstage, demanding perfection. When nearly the entire band quit on the eve of a gig in March 1970, Brown replaced them overnight with the Pacemakers from Cincinnati—Bootsy, Catfish, and their crew. These young players were bursting with “Soul Power” and hungry to prove themselves. In Brown, they found a mentor (Bootsy later called him a father figure) who pushed them to get sharper each night. In turn, they pushed Brown’s music to new heights of rawness and streetwise urgency. The J.B.’s were the perfect band to carry Soul Brother Number One into the Black Power era of the early ’70s. Together, they traded the sleek, choreographed polish of the ’60s for a hard, uncut funk sound that captured the defiant spirit of the time. Sex Machine was the first major document of this new sound—a double-LP funk manifesto that both cemented Brown’s crown as King of Funk and pointed toward the future.

From the moment Sex Machine hit turntables in 1970, musicians knew something had changed. Its influence reverberated widely—especially in the birth of hip-hop a decade later. Clyde Stubblefield’s vicious drum patterns and Bootsy’s rubbery bass lines have been sampled on countless rap records; the album launched a thousand hip-hop samples and breakbeats. The break from “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” became a secret weapon for DJs and B-boys in the Bronx—one of those crucial funk breakbeats that helped kickstart hip-hop. As Rolling Stone later noted, Brown, Clyde, and Bootsy “played such a large part in the sound of hip-hop. Listen to these songs with that in mind and you’ll hear it.” The legacy of Sex Machine runs through groove-centric music that followed, from Parliament-Funkadelic (where Bootsy took funk to outer space) to Prince, Michael Jackson, and beyond. Brown had drawn the blueprint for modern funk—a style defined not by hummable melodies or tidy songcraft, but by rhythm, repetition, and feeling. “Brown’s music was about groove… he got to the groove being the dominant element of the music,” producer Rick Rubin observed. To ears attuned to the funk-laden ’70s, the sampled beats of ’80s rap, and later jam-band experiments, Sex Machine still sounds fresh. It’s the wellspring of so much, yet the raw power on these tracks still sends shivers.

The Sex Machine double LP isn’t just about its title track. It’s a panoramic live experience, moving from extended funk workouts to snippets of earlier soul hits, sequenced like a single continuous show. On vinyl, Sides A and B were presented as “live” (in truth, cut in the studio with applause added), while Sides C and D captured a real concert in Brown’s hometown of Augusta, Georgia. Yet the record plays almost like one performance—multiple songs woven into a long, breathless piece of music. Brown was a master of the medley. With tightly rehearsed transitions and cue-driven segues, he could switch grooves so precisely you’d instantly forget the previous tune. On Sex Machine, this approach is on full display. After the sprawling “Sex Machine,” the band drops into “Brother Rapp,” a Part I & II funk jam that digs even deeper into the pocket. The groove is “a relentless, mesmeric juggernaut,” as one critic described it. Bootsy and Catfish lock in tightly, the guitars and bass bouncing around each other in a trance-inducing pattern. Brown’s vocals ride lightly on top; “Brother Rapp” is more vibe than song. Lyrically, it carries a message—Brown later said it was about letting the brothers rap, a plea for voices to be heard—but onstage it serves chiefly as a showcase for the band’s new funk vocabulary. Under close listening, a groove like “Brother Rapp” remains hypnotic. The interplay of the rhythm section, with congas pattering (hear Johnny Griggs on percussion) and two drummers syncopating around each other, creates a dense polyrhythmic stew. The repetition becomes intoxicating; subtle variations in Bootsy’s fills or Catfish’s chords become thrill points. This is the essence of funk: finding infinity in a single chord, a single vamp.

The band’s ability to stretch a three-minute song into a ten-minute workout is the marvel here. Take “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose.” The original 1968 version was tight and punchy, but when Brown recut it in July 1970 with the new J.B.’s, it became a show-stopping epic. On the album, “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” runs about 6½ minutes (and some performances went even longer). The energy is cranked up from the earlier version. The tempo is brighter, the groove more aggressive. Catfish Collins introduces a revamped guitar riff—a syncopated single-note line that meshes tightly with the bass, almost like a second percussion instrument. Clyde Stubblefield lays down an intense “Funky Drummer”-style beat—all fast syncopations on the hi-hat and ghost-note snare rolls—giving the track extra adrenaline. And then there’s Bootsy, who absolutely owns this track. He “took the James Brown bass chair to its busiest, most in-your-face level,” pushing a rambunctious bass groove to the forefront.

Where the old bass line was content to repeat a simple phrase, Bootsy expands it into a two-bar saga, climbing up the scale with chromatic runs and then thumping back down to the root on the One. The effect is monstrous—the whole band sounds turbocharged. Midway through, Brown breaks the music down: “Clap your hands! Stomp your feet!” he yells, cueing a segment that leaves only the bare rhythm thumping. This stretch—Bootsy popping octaves, Clyde riding the cymbal, the horns slicing in for stabs—became pure catnip for generations of DJs and producers. In 1970, it was simply the sound of a band on fire, stretching out and cutting loose. You can imagine the Apollo crowd—clapping on the backbeat, some jumping in the aisles—while Brown prowls the stage, letting his band groove at length, only to pull them back with a shriek and a flick of his wrist. The chemistry of this unit was so airtight that even at their most stretched-out, they never lose the pulse. It’s a tightrope walk between discipline and abandon: they give it up but never quite turn it loose unless Brown permits.

Another gem in the extended funk repertoire here is “Mother Popcorn.” Originally a No. 1 R&B hit in 1969 (co-written by saxophonist Pee Wee Ellis as an ode to a dance), “Mother Popcorn” appears as the rousing finale of the live set on Sex Machine. By this point, Brown’s shirt is surely soaked through, but he’s not dialing back. The band tears into “Mother Popcorn” with turbocharged propulsion. Bootsy hammers a feverish two-note riff while Maceo Parker (alto sax) and St. Clair Pinckney (tenor sax) blast the infamous popcorn horn line—a zigzagging figure that mimics a popping motion. Brown’s voice rides high and hoarse: “You got to have a mother for me!” he howls, a line half-nonsense, half raw sexual energy. Mid-song, he might drop to a knee and do the Popcorn dance himself, feet shuffling rapidly, then leap back up with a scream—“Good God!” It’s funk theater at its finest. Under close listening, the groove still holds up mightily—the guitars, bass, and two drummers create a syncopated storm. Notably, on the album mix, this track (like others on side four) was truly recorded live in concert at Augusta’s Bell Auditorium and released without the phony crowd overdubs. The rawness is apparent: you hear the audience reacting, the cavernous reverb of the hall, the band feeding off the shrieks as they hit each break. Compared to the 1969 studio single, the live “Mother Popcorn” here is longer, looser—extra vamps, improvised call-and-response with the audience. Five decades on, it still compels movement.

Crucially, Brown knew even the hardest funk barrages need contrast. Part of what makes Sex Machine a captivating live album (and not just a relentless jam session) is how it balances extended workouts with earlier soul cuts and ballads. In the midst of the funk fury, Brown cools things down with a few numbers from his 1960s bag: the torch song “Bewildered,” a snippet of “I Got the Feelin’,” the heart-rending plea “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World,” and, of course, his eternal closer “Please, Please, Please.” Some last only a minute or two, serving as breathers—brief islands of melody amid the uptempo jams. When Brown slides into a slow number like “Bewildered” on side two, the transition is seamless; the band simply downshifts and suddenly the hardest working man in show business becomes the soul crooner, testifying under a lone spotlight. His voice on the ballads is still raspy from the funk shouting, which lends extra pathos—as if he’s baring his soul after exhausting his body. The inclusion of older hits shows Brown saluting his past even as he forges the future. In one concert, he can bring the audience from the doo-wop plea of “Please, Please, Please” straight into the hyper-modern funk of “Sex Machine.” That set list balance was shrewd—it kept longtime fans happy and grounded the show in showmanship, while unleashing the new funk bit by bit. On the album, you get a full panorama of James Brown’s genius: the lover, the showman, the preacher, and the funk inventor, all in one evening.

The 1970 Sex Machine album is a raw document of a band and sound in metamorphosis. It’s useful to compare its gritty intensity to another celebrated live recording of the same J.B.’s lineup: Love Power Peace: Live at the Olympia, Paris 1971. That Paris show (finally released two decades later, in 1992) captured Brown and the Collins brothers at the tail end of their year together, in full flight on a European stage. The performance on Love Power Peace is incendiary—some consider it among Brown’s greatest live albums—with excellent sound and the band in peak form. But it’s also more polished. By March 1971, the J.B.’s had road-tested their act around the world; in Paris, they delivered a tightly arranged revue. The recording is clean, multi-tracked, every horn line in place, every transition executed like second nature.

The set overlaps with Sex Machine (“Brother Rapp,” “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose,” “Sex Machine”) and adds new hits like “Super Bad,” plus soul interludes by Bobby Byrd and Vicki Anderson. Side by side, you notice that on Love Power Peace, the songs run slightly shorter—“Sex Machine” under nine minutes, “Give It Up or Turnit a Loose” around five—and the delivery is more streamlined. It was intended to be Brown’s grand live album for 1972 (originally a triple LP), and it feels like a polished product of a revue at its apex. Sex Machine, by contrast, hits like a grenade. The first half (with its simulated live ambience) has a gritty, almost bootleg quality—you can sense the band testing how far out they can go, stretching and flexing. The second half, recorded live in a less controlled environment (Brown’s home turf in Augusta), has a murkier, booming auditorium sound. Brown didn’t intend Sex Machine to be an audiophile showcase—he intended it to grab you by the collar. As one reviewer noted, even if parts weren’t truly live, “it doesn’t really matter because the album is a stone-cold classic and a searing funk manifesto.” The rough edges are the point.

Other live albums in Brown’s catalog each have their character: the original Live at the Apollo (1963) is a polished, taut masterpiece of soul showmanship; Live at the Apollo, Volume II (1968) catches him pivoting toward funk with elongated medleys and a bigger band; Revolution of the Mind: Recorded Live at the Apollo, Vol. III (1971)—recorded about a year after Sex Machine—showcases a later lineup (with some of the old members like Maceo back in the fold) and has ferocious moments, though by then the Collins brothers had departed. Yet Sex Machine holds a unique place even among these giants. It is the pivotal live document of James Brown’s funk revolution. Unlike the more finely crafted Apollo releases, Sex Machine feels like you’ve snuck into an after-hours jam—unfiltered, bawdy, locked in the groove. Its impact comes from that raw intensity, the sense that at any second Brown might scream “GOOD GOD!” and take the band somewhere unplanned and dangerous. You hear him call out individual players—“Bootsy! Take it to the bridge!” or “Give the drummer some!”—and the musicians respond in a millisecond, unleashing a solo or break that raises the hair on your neck. The interplay between frontman and band is jaw-dropping: Brown essentially uses the band as his instrument, conducting with shouts, dance steps, and hand signals, and they answer with razor-sharp precision. It’s call-and-response on a grand scale—not just between Brown and Byrd or Brown and the crowd, but between Brown and his entire ensemble.

So, what is the lasting legacy of Sex Machine in funk history? It’s a touchstone—the record you hand someone who asks, “What was James Brown’s funk about?” It captures the birth of 1970s funk in uncut form: rhythm over melody, the stage (or studio) as a space for extended exploration, showbiz slickness fused with raw Black musical power. It also immortalized a particular lineup whose impact far outweighed its brief tenure. The fact that Love Power Peace is the only other live recording of the original J.B.’s underscores how precious Sex Machine is. As the 1970s rolled on, Bootsy and Catfish Collins took their talents to Parliament-Funkadelic, carrying Brown’s innovations into the next decade’s psychedelic groove. Maceo Parker and Fred Wesley would also join that P-Funk orbit after reuniting with Brown, spreading the gospel of the One. Brown kept churning out hits through the early ’70s (“Soul Power,” “Get Up, Get Into It, Get Involved”—both nurtured in the Bootsy era), but many agree the Sex Machine period was an unrepeatable peak. It was the moment James Brown pushed his music to the edge—and changed the course of popular music in the process.

To ears raised on everything from disco to hip-hop to modern R&B, the album doesn’t feel dated so much as elemental. These grooves are part of the DNA of contemporary music. But nothing matches hearing them in their original form, played by a band of young virtuosos led by a man at the height of his powers. There’s a reason that, whenever people speak of James Brown’s live prowess, Sex Machine sits alongside his Apollo shows. It isn’t as polished as those earlier records—it’s dirtier, heavier, more chaotic. In that controlled chaos lies the soul of funk: freedom and discipline dancing together. As the last notes of “Sex Machine (Reprise)” and “Super Bad” hit, you can almost hear Brown addressing an exhausted, ecstatic crowd: “Good night, folks—and remember, whatever you do—get up, get into it, and get involved!” The revolution he unleashed at the Apollo in 1970 still reverberates—a live document that remains a gold standard of funk, sending shivers down spines and making people get on up to this day.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)