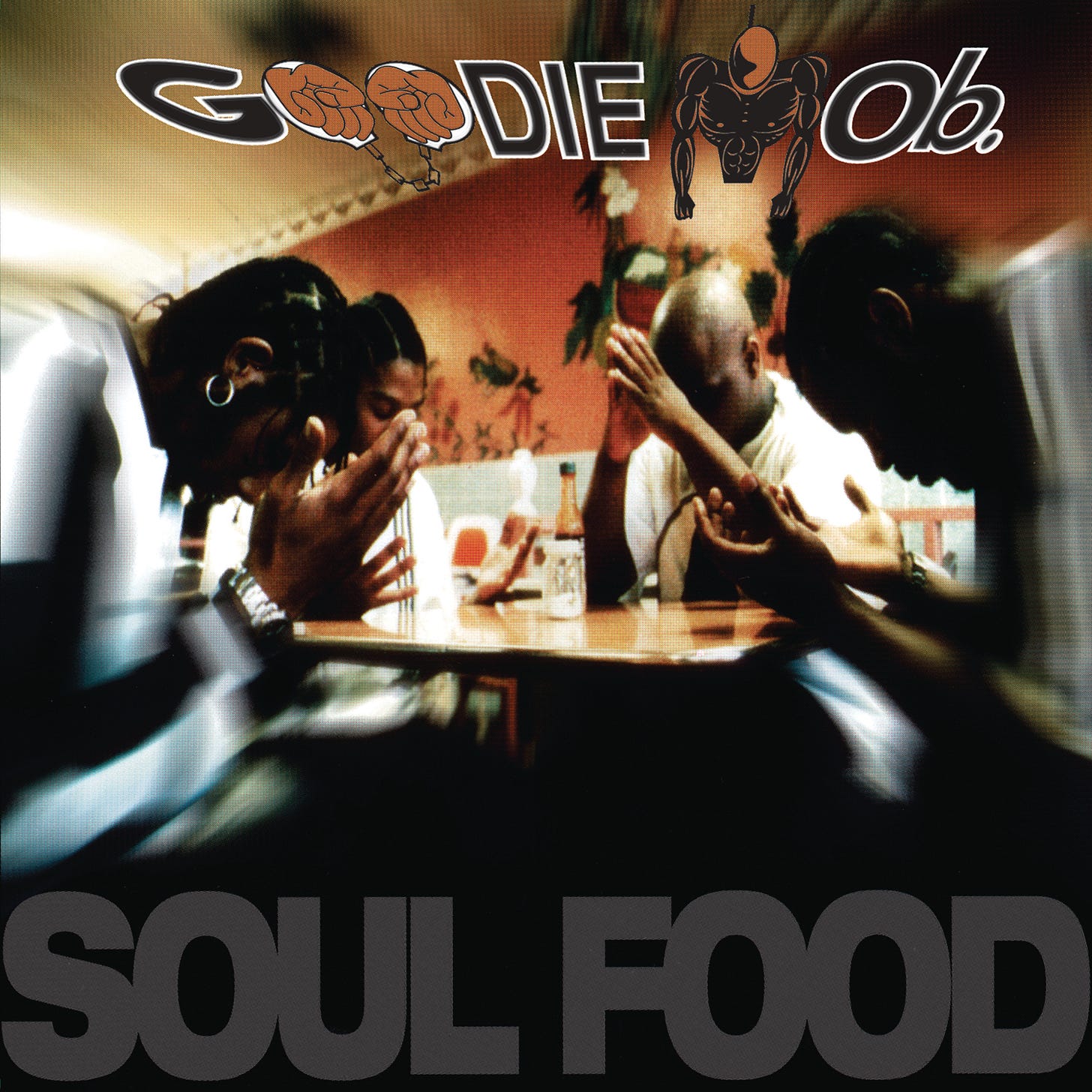

Milestones: Soul Food by Goodie Mob

Goodie Mob invited us to their table to break cornbread and share truths. The feast they cooked up in the Dungeon nourishes, and its spirit of community and perseverance still tastes like deliverance.

After Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, the next step feels like an invocation from the Georgia clay and the church pew. It was born in the Southern Baptist churches and the red clay of southwest Atlanta, then forged in the Dungeon, where the Organized Noize’s legendary basement studio was equal parts tabernacle and sonic laboratory. In that cramped, musty space beneath late producer Rico Wade’s house, sacred traditions met street rituals: voodoo incantations collided with the warm tones of Rhodes organs and gospel harmonies, as young rappers freestyled amid burning incense and crawling instrumentation. Soul Food, the collective’s 1995 debut, originated from this crucible, sounding like a prayer delivered over a funk groove. It blended the corporeal and the spiritual, the desperation of Atlanta’s streets and the exaltation of Sunday worship—an essential text that hasn’t lost one ounce of its power to inspire and provoke, even as its truths remain as unprovable (and undeniable) as any sacred revelation.

In the mid-1990s, Dungeon Family compatriots OutKast may have been the face of Atlanta’s new hip-hop movement, but Goodie Mob was its spine, its vital nervous system. While OutKast’s Aquemini is widely hailed as a masterpiece of Southern rap, Soul Food is the essential nerve running through it all. Goodie Mob’s four voices—Cee-Lo, Big Gipp, Khujo, and T-Mo—attacked songs with raw harmonies and rap flows like a Southern-fried Wu-Tang Clan or a spiritual Public Enemy. They delivered something that was at once a feast and a famine: music as nourishing as a home-cooked meal, yet as chilling as standing out in the cold. The album is everything at once: the feast, the list of secret family recipes, the feeling of standing out in the cold. It captures the full spectrum of Black Southern life: the comfort of community and the ache of poverty, the hope of redemption and the reality of oppression, all within an hour of music.

Goodie Mob’s own origins are as richly storied as their music. The name itself is layered in meaning; on the album, they define Goodie Mob as an acronym (“the Good Die Mostly Over Bullshit”), a mordant reminder of the fate of too many young Black men. More colloquially, it sprang from the “goodie bags” that members T-Mo and Khujo used to carry their weed and cash back in the day. Fittingly, the group coalesced organically out of Atlanta’s music scene in the early ‘90s. Originally, Goodie Mob was just two friends: T-Mo (Robert Barnett) and Khujo (Willie Knighton Jr.), who performed as a duo called The Lumberjacks and even guested on OutKast’s debut album in 1994.

Meanwhile, Cee-Lo Green (Thomas Callaway) and Big Gipp (Cameron Gipp)—childhood friends of OutKast—popped up on the same OutKast album. Cee-Lo’s show-stealing verse on “Git Up, Git Out” earned him a Source Award hip-hop quotable for lines that defined Goodie Mob’s essence: “I get high, but I don’t get too high.” That single lyric proclaimed a worldview of balance and duality—living in the pitfalls of the hood but refusing to lose oneself completely. Cee-Lo, the son of not one but two Baptist preachers, had been honing his musical gifts in church choirs since childhood. He and T-Mo had known each other since nursery school. Khujo had a reputation around Atlanta as a straight-up brawler, the kind of guy you wanted on your side in a scrap. And Big Gipp? He made an unforgettable entrance the first time they all met: rolling up to the Dungeon in a Cadillac, wearing a white lab coat fresh from beauty school classes. “Ancient” souls in twenty-something bodies, these four young men found a kinship in their differences.

Their chemistry was evident from the start, but interestingly, Goodie Mob only formed as a quartet when a record deal was on the line. In 1994, LaFace Records chief L.A. Reid dangled the prospect of a contract—but only if these individual talents united as a group. They took Reid’s offer and planned to join forces just long enough to make one album, then spin off into separate projects. Thankfully, the breakup never came (at least not until much later), because together these four had alchemy that none could replicate alone. You can hear that hard-won unity in every bar of Soul Food. The group’s formation may have been pragmatic, but their bond was spiritual. Once Goodie Mob came together, they never doubted their mission: to represent their reality and uplift their people by telling hard truths.

From the very first seconds, Soul Food announces itself as rap born of struggle and devotion. Instead of kicking off with a rapid-fire verse, the album opens with a weary croon: “Lord, it’s so hard living this life,” sings Cee-Lo Green in a raspy, plaintive wail. This isn’t a typical hip-hop intro. Absolutely not. It’s a benediction, a church spiritual beamed into a ‘90s rap album. Cee-Lo’s voice, the raspy hallelujah of a preacher’s son, scratches at the heavens with half-angel, half-devil urgency. In that single line, he channels the blues and gospel of his upbringing into the contemporary plight of the streets. You can practically feel the duality in his tone: gifted and damned, righteous yet wicked. That dual nature runs through the album’s veins. Goodie Mob draws from the same poisoned well as the blues greats (singing of suffering and temptation), but they feverishly try to purify it with hope and faith. Over dusky Rhodes piano chords and organ drones, Goodie Mob testify about a world where sin lurks close at hand, but the promise of salvation is just as real, whether through music, prayer, or a hot plate of soul food at week’s end. Freedom is the only goal, but demons dog their every step.

When Soul Food dropped in November 1995, the expectations were modest. The Atlanta rap scene was still defined mostly by bass-heavy party music and player anthems. LaFace may have hoped for a Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik Part II from their new signees, but Goodie Mob delivered something altogether different—a work more akin to Paradise Lost set in East Point, ATL. At a time when much of Atlanta’s rap focused on “booty shake” anthems and glossy anthems, Soul Food was defiantly ancient in soul and tone. These were spiritual sinners from the SWATS (Southwest Atlanta) who merged socio-political commentary with down-home folk wisdom and dope-boy realism.

Though OutKast were like the cool cousins mixing pimp flair with poetry, Goodie Mob were the older siblings passing the blunt and dropping knowledge in a circle of scuffed college dorm couches. They brought a heady mix of spirituality, cerebral introspection, Black mysticism, and topical commentary to Southern hip-hop. And crucially, they did it while embracing their Southern roots unabashedly. The album is laced with references that any Atlantan would recognize—from whuppins and clay roads to fish frys and the old Omni Coliseum. Cee-Lo’s intro hymn “Free” sounds like a Negro spiritual beamed straight out of a rural church revival into the studio. It’s followed by the title track, “Soul Food,” which lovingly describes a Sunday family supper with Mom at the stove and every relative welcome at the table. In 1995 Atlanta, a city on the cusp of post-Olympics gentrification, Soul Food plays like an elegy for a rapidly changing community—name-checking streets, neighborhoods, and old landmarks that defined an era. To listen now is to step into a time capsule of pre-millennium Atlanta: Bankhead before the boom, Techwood before the tear-down, the SWATS before the city got glossed over for the world’s stage.

At the thematic heart of Soul Food is a profound exploration of sin and redemption. Goodie Mob took the often-mocked idea of “struggle rap” and elevated it into genuine art. Every member grappled with inner demons and the hope of deliverance. Faith in Soul Food is constantly tested but never abandoned. The push-and-pull between doing wrong and striving for righteousness is embodied in the group’s very name (Good and Evil are always at war in a Goodie Mob song)—the album’s imagery swings between demons at the doorstep and salvation at Sunday dinner. Few albums have better captured the feeling of being young, Black, and under siege in America while still holding on to hope. Soul Food makes you feel the hunger in your belly one day and the communion of a family feast the next. There is pain here—poverty, violence, injustice—that eats at the spirit, but there is also nourishment: love, unity, and belief strong enough to keep a person alive. When Goodie Mob rap about food, it’s more than just sustenance. Actually, it’s soul medicine.

The album’s signature songs drill even deeper into that tension between fear and faith. Take “Cell Therapy.” Built on a spooky, music-box glockenspiel loop and an ominous, unresolved piano riff, the track became Goodie Mob’s breakout hit and a centerpiece of paranoia in hip-hop. Over a slow-rolling beat as eerie as an urban night full of unseen threats, the Mob deliver verses steeped in Orwellian anxiety and Illuminati lore. It’s as if George Orwell met William Cooper (author of the conspiracist manifesto Behold a Pale Horse) in a Georgia trap house. “Cell Therapy” channels 90s survivalist conspiracies about government surveillance, New World Order plots, and black helicopters circling overhead. “Who’s that peeping in my window? Pow! Nobody now!” goes the haunting hook, a line that speaks to both intrusion and resistance—the sense that oppressive forces are always watching, and the instinct to fight back. When Goodie Mob recorded this song, the Oklahoma City bombing was fresh in the headlines, and militias lurked on the fringes of American culture. Cell Therapy repurposed those paranoid ideas through a Black survivalist lens: the hood as a warzone, the government as a suspect entity, and knowledge (however far-fetched) as the only shield. Yet amid talk of concentration camps and constitutional suspensions, the song’s community spirit is potent. It’s a record that celebrates community and the exposing of lies, revealing how the hood can see through false promises.

Over a beat as dusty as a Georgia backroad, with “Thought Process,” T-Mo opens up about scrounging for change to get by, trying to stay focused and keep his head on straight. His consciousness doesn’t stem from self-righteousness, but out of pain—he’s seen so many of his friends die that wisdom came as a necessity, not a luxury. T-Mo grimly notes he went to “too many funerals before he could grow facial hair,” a line that lands like a punch to the gut. Meanwhile, Khujo’s verse on “Thought Process” might be one of the earliest references to the “trap” in popular rap lexicon. “Khujo is in the trap,” he raps—and in 1995 that term was not yet the ubiquitous label for Southern drug-hustling culture it would become. Here, Khujo uses it bluntly: life is trap or die, nearly a decade before T.I. and Jeezy made those words famous. The effect is to cast their everyday life as its own kind of conspiracy or predestination—a struggle to break free from the cycle that ensnares young Black men.

Toward the middle of the album comes perhaps its most haunting moment, the song “I Didn’t Ask to Come.” Even the title reads like a weary sigh at the burden of existence. Over a somber, bluesy melody, the group contemplates mortality and fate with unflinching honesty. In what might be Soul Food’s most chilling verse, T-Mo delivers an opening line that hits like a prophecy: “Every day somebody gets killed… It’s 1995 and a nigga wanna live.” (In plain terms: it’s 1995 and a Black man wants to survive.) That raw plea sums up the album’s prescient confession of mortality. Decades later, the sentiment sadly endures: every day brings new tragedy, and the simple act of living to see tomorrow can feel like a luxury. As the song unfolds, Goodie Mob members trade verses that blend weariness with resolve. They sound like old souls tired of funeral after funeral, yet still striving for meaning in why they’re here. Soul Food doesn’t offer easy answers to these big questions—instead, it offers the comfort of camaraderie and the courage to face another day.

Across all these tracks, Organized Noize's production provides a richly textured yet uncluttered canvas. The album’s sound is steeped in live instrumentation and bottom-heavy grooves that draw from the entire continuum of Black music. Samples of Soul Food are few and subtle; instead, the funk rolls in real time. Bass lines slither, guitars strum faintly in the background, and churchy organs hum like a Sunday service. It’s music you feel in your bones. Some moments sound like accidental séances captured on tape—as if some ancestral spirit was summoned in the Dungeon, echoing through those minor-key piano loops and atmospheric hums. When many East Coast peers were chopping up James Brown loops and West Coast producers were layering synthesizers, Organized Noize took a distinctly Southern approach: recreating the feeling of soul and funk classics without outright sampling them. They even recorded parts of the album at soul legend Curtis Mayfield’s Atlanta studio, as if to draw directly from the well of Southern soul.

Soul Food’s impact on hip-hop history is undeniable, even if Goodie Mob themselves never attained the pop-icon status of their Dungeon Family brethren OutKast. This album was the sinew beneath OutKast’s face—the strong supporting muscle under the flashy visage of Southern hip-hop’s rise. Goodie Mob gave the Dirty South its conscience and its rallying cry. In fact, Soul Food literally introduced the term “Dirty South” into the hip-hop lexicon. The song “Dirty South” (track four on the album) wasn’t just a posse cut; it was a manifesto. Conceived by Goodie affiliate Cool Breeze and featuring Big Boi of OutKast, that song coined a name for Southern hip-hop’s burgeoning movement. With references to Atlanta’s infamous Red Dog police unit and history lessons stretching back to slavery, “Dirty South” solidified a regional pride and pain in a way no one had before. It’s richly ironic that a group as political and spiritual as Goodie Mob ended up giving rise to the nickname for a Southern rap explosion often associated with crunk party anthems and strip-club beats. But that speaks to Goodie Mob’s role: they were the unifying thread, tying the South’s past to its future.

From Atlanta to Houston to New Orleans, the ripple effects of Soul Food can be traced in the Southern artists who followed. Whether it was the socially conscious tracks of a young T.I., or the way OutKast carried Dungeon Family’s eclectic spirit forward, Soul Food set a template. And its influence didn’t stop at the Mason-Dixon line. Look to Compton’s introspective superstar Kendrick Lamar, for example, and you’ll hear Dungeon Family echoes in his work. Kendrick’s acclaimed albums blend searing social commentary with funk/soul influences and spiritual overtones—a recipe Goodie Mob was cooking up in ’95. It’s simultaneously an indictment of the powers that be, a call for unity and love, a repentance for sins, and a requiem for those we’ve lost. If the Dungeon Family mantra was “the South got something to say,” then Soul Food was its most coherent and soulful statement—musically, spiritually, philosophically.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)