Milestones: Stankonia by OutKast

Stankonia remains celebrated as a masterpiece, partly because it captured the last time André and Big Boi’s visions fully connected.

It begins in the year 2000 inside the Stankonia Studio, a converted Atlanta facility once owned by Bobby Brown. André “3000” Benjamin and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton had spent years renting time in other studios; by purchasing their own space and naming it Stankonia, they could work on music whenever inspiration struck. The sessions lasted nearly a year. Big Boi spent long hours in the studio, bringing in musicians and shaping beats. André mostly stayed home painting lyrics on his walls and would stop by to record his verses, creating the jagged, riffing anthem “Gasoline Dreams.” Their independence also meant the album’s off‑kilter experiments did not have to answer to a label schedule. They took advantage of that freedom by drawing from outside hip‑hop—Jimi Hendrix, Little Richard, Prince, George Clinton, and salsa records—and mixing those influences with the cadence of the Dirty South. Big Boi later described Stankonia as whatever the funkiest thing could be, whether a purple hue or funky‑ass music.

As their fourth studio album, Stankonia still feels like a sonic mural spray‑painted across cosmic underpasses. The album opens with “Gasoline Dreams,” a rock‑scorcher propelled by fuzzed‑out guitars and a choir intoning “Don’t everybody like the smell of gasoline?” The song’s critique of dependence on fossil fuels and the empty pursuit of the American Dream lands like a protest chant; André and Big Boi namecheck racism, drug addiction, and national complacency. Big Boi matches André’s vitriol and proves that the “southernplayalistic pimp” persona from their debut had evolved into a political voice. The track’s energy nods to Public Enemy’s rock‑influenced production while prefiguring the fury that would later fuel modern trap.

On “B.O.B. (Bombs Over Baghdad),” the duo and their production partner Mr. DJ harness the restless energy of drum and bass, gospel, Hendrix‑style guitar solos, and a full gospel choir. The track hums at 155 beats per minute and overlays techno pace with dense scratching. 2000’s hip‑hop rarely moved past 90–100 bpm; André wanted to capture the speed and ecstasy of rave culture. The result is an anti‑war anthem released as the U.S. prepared to invade Iraq. André’s hook (“Don’t pull the thing out unless you plan to bang, bombs over Baghdad!”) is a warning to both warmongering governments and street hustlers. Big Boi’s verse encourages peers to “make a business for yourself,” a message that resonated with both corporate and street audiences. The entire track accelerates to the verge of collapse before a choir and guitar solo swirl it into transcendence. It remains one of the most explosive singles in hip‑hop history.

Beyond the cosmic agitation, “Ms. Jackson” is domestic introspection. Both André and Big Boi addressed estranged mothers—Big Boi to his children’s mother, André to the mother of his then‑partner Erykah Badu. The song’s twisted keyboards and slippery drums make an unorthodox single, and the hook’s apology to “baby’s mamas mamas” became ubiquitous. Big Boi’s verse is raw, venting frustration at meddling friends and family who have “got your ass sent up the creek.” André’s verse acknowledges the dissolution of a relationship and vows to remain a present father. Against a melancholy melody drawn from early Prince and P‑Funk, the duo humanized fatherhood and co‑parenting, turning a personal apology into a global hit. The song topped the Billboard Hot 100 and won a Grammy, evidence that commercial success need not come at the expense of complexity.

Between these poles of protest and apology lies a galaxy of experiments. “So Fresh, So Clean,” produced by Organized Noize, is a slow‑rolling funk that imagines the duo strutting in winter storms cooler than Freddie Jackson sipping a milkshake. The horns on “Spaghetti Junction” recall L.A. soul; the song contemplates the obstacles young Black men face as they try to escape poverty. An early verse from Killer Mike on “Snappin’ and Trappin’” heralds his future stardom; he brags about turning raw cocaine into crack with “pen and pixel” that makes “violence more graphic.” Each song is a world unto itself, yet shares a commitment to pushing hip‑hop beyond comfort zones.

The album’s midsection deploys a kaleidoscope of textures. “Humble Mumble” marries upbeat Caribbean grooves with abrupt beat shifts. Big Boi raps about grinding through adversity, while André ponders the contradictions of activism, noting that speeches often reach only those already converted. Erykah Badu enters like a free‑form chant, her vocals swirling around the beat and gradually taking over the song. Rolling Stone described the duo as merging André’s “third‑eye consciousness” with Big Boi’s street style, and nowhere is that more evident than here: Big Boi grounds the track in hustler pragmatism while André and Badu float above the fray. The interplay creates friction that crackles, but instead yields momentum—a hallmark of Stankonia.

On “Red Velvet,” the duo warns against flaunting wealth over a stuttering beat that stops and starts like a skipping CD. Big Boi spells out his verse like a K‑Solo impersonation, building tension, while André uses a helium‑voiced style that would later define his The Love Below persona. The chorus cautions those bragging about their poundcake that “them dirty boys turn your poundcake to red velvet”—a metaphor for flashy riches turning into bloodshed when jealousy and robbery strike. The track’s unsteady rhythms embody the unease of material success; it feels like an Aquemini outtake, but its funk groove roots the album between cosmic flights.

“Gangsta Shit” is perhaps the album’s most straightforwardly aggressive moment, yet even here OutKast subverts the genre. Over a slow 808 burn, the Dungeon Family posse—Slimm Cutta Calhoun, C‑Bone, T‑Mo, and Killer Mike—spell out what gangster means. Big Boi’s verse turns his flow into a spelling bee, while C‑Bone and Slimm lean into drawlin’ funk. André enters with his signature eccentricity: “We’ll pull your whole deck, fuck pulling your card/and still take my guitar and take a walk in the park.” The line emphasizes that true strength comes not from violent posturing but from artistic freedom. The track’s hi‑hats foreshadow the proto‑trap rhythms that would dominate Southern rap in the mid‑2000s. Even as the posse brags, the message is not about murder fantasies but about community codes and creative authenticity.

Where we get past the raw bravado, “I’ll Call Before I Come” delivers wry sensuality. The track is built on a playful funk groove reminiscent of late‑‘70s Sly Stone. Big Boi and André express a gentlemanly approach to sex: André claims a preference for “old school, regular draws,” while Big Boi emphasizes his partner’s satisfaction. The duo invites Memphis rapper Gangsta Boo and Atlanta’s Eco to deliver the final word, giving female perspectives equal weight. The inclusion of women ensures that the song is not an empty boast but a conversation about mutual pleasure. Its off‑kilter hook and lyrical humor lighten the album’s heavier themes without breaking its thematic integrity.

As the album deepens, the tone darkens. “Toilet Tisha” is a haunting ballad about a 14‑year‑old girl who becomes pregnant and ultimately dies. The watery synths and guitars evoke mid‑1990s Prince, while André sings through heavy vocal distortion, making his voice nearly unrecognizable. Big Boi’s spoken‑word verse paints the harsh details the singing hints at. The narrative doesn’t exploit tragedy but uses it to humanize those lost in cycles of poverty and despair. The track’s somber mood is so convincing that it’s the album’s darkest song. Its presence reveals OutKast’s willingness to tackle topics seldom addressed in mainstream hip‑hop.

A psychedelic dedication to everyday women follows in “Slum Beautiful.” André, Big Boi, and Cee‑Lo praise the beauty of women from their neighborhoods. The track’s backward‑masked guitars and resonant bass evoke Jimi Hendrix and Graham Central Station. Cee‑Lo’s verse is evocative: he envisions traveling through time, tasting outer space, and seeing the face of God in his lover. The song drips with cosmic romance and reaffirms the duo’s Afrofuturist lineage; early in André’s life, he kept a poster of Plutonia, a 1950s Russian sci‑fi novel, on his wall. That poster inspired the group to imagine Stankonia as a futuristic utopia, and the album’s name combines “stank” (funky) with Plutonia. “Slum Beautiful” thus situates everyday love within interstellar fantasies, a hallmark of Afrofuturism.

The album ends with “Stankonia (Stanklove),” a funk‑drenched slow jam channeling P‑Funk ballads. The track features Bootsy‑inspired basslines and Sleepy Brown’s vocals. Big Rube delivers a spoken‑word piece, promising a love so profound it feels like a “cataclysmic shockwave.” The song fades into echoes instead of finishing, suspended in Stankonia’s utopian soundscape. It shows how the album moves from the political to the cosmic, from social critique to sensual liberation.

Throughout Stankonia, the interplay between André and Big Boi drives the narrative. André emerges as the visionary, his lyrics filled with metaphors and triple entendres. He conjures Afrofuturist imagery, flips unpredictably, and occasionally sings in falsetto. Big Boi is the anchor, his razor‑sharp street poetry and southern drawl grounding the music. On “Gasoline Dreams,” he matches André’s protest line for line; on “Humble Mumble,” he raps about coping with adversity while André muses about activism. Their personas clash and converge; the friction yields unpredictable shifts in mood and rhythm. Big Boi’s focus on hustle and community ensures that the album never floats too far into abstraction, while André’s flights of fancy push the music into new dimensions.

Another key dynamic is the role of Earthtone III, the production collective of André, Big Boi, and Mr. DJ. Together, they handled most of the production, inviting local musicians to play live instruments. Live guitar, bass, and horns cohabit with drum machines and turntables. On “B.O.B.,” they layered a guitar solo reminiscent of Jimi Hendrix over a drum‑and‑bass beat; on “Red Velvet,” they built a skittering beat that stops and starts unexpectedly; on “Slum Beautiful,” they used backward‑masked guitars for a psychedelic feel. The result is an album that refuses to settle into a single style. As Big Boi told a Fader writer, Knox Robinson, in 2000, they would finish studio sessions, head to Big Boi’s house, and party until the afternoon. The nights often ended in the Boom Boom Room, where unmastered tracks blasted while the crew drank Hennessy. The chaotic environment fed into the album’s density and unpredictability.

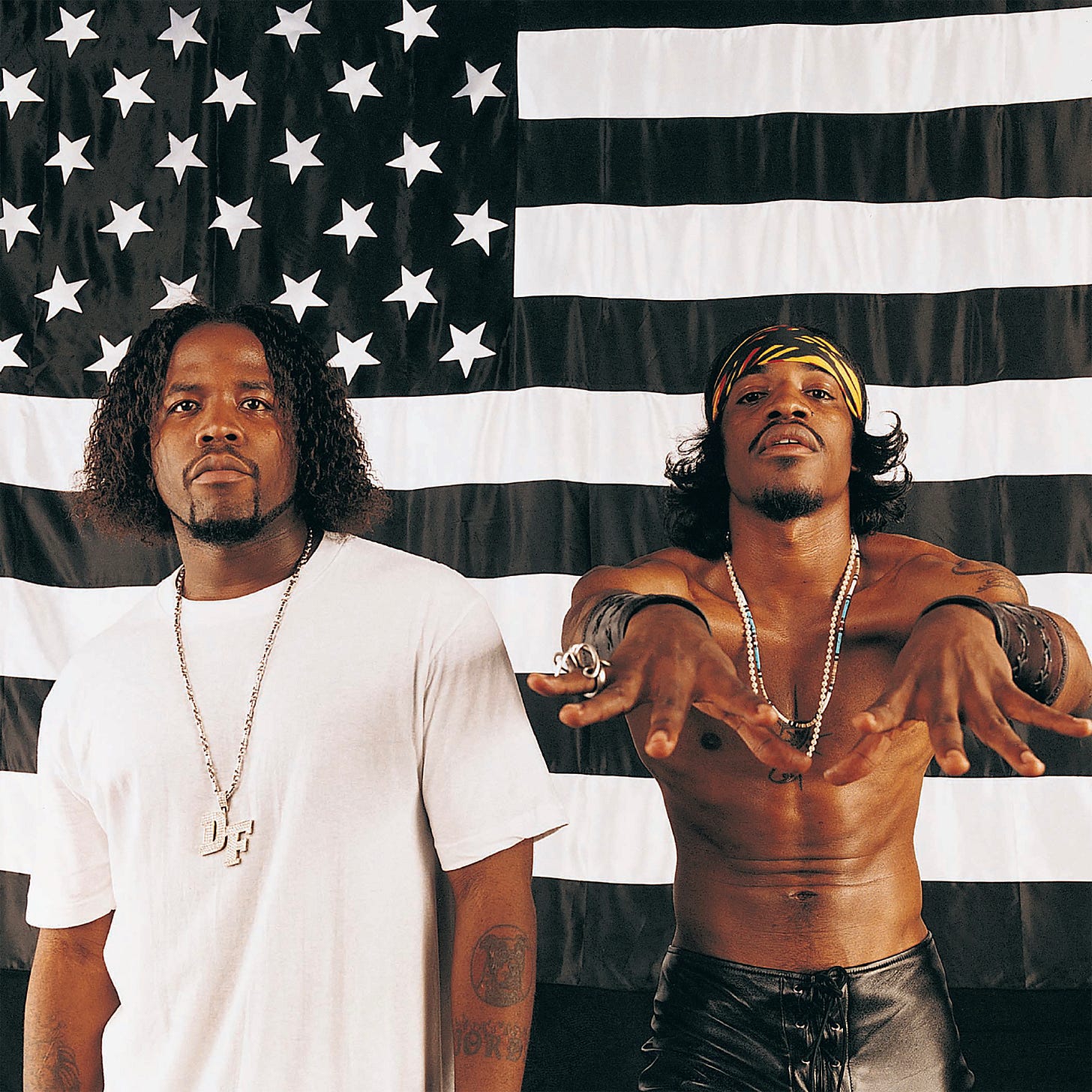

Stankonia also engages with the broader Southern rap scene. The posse cuts “Gangsta Shit” and “We Luv Deez Hoez” feature the extended Dungeon Family. Killer Mike’s debut verse on “Snappin’ and Trappin’” positions him as a star. The album features guests like Goodie Mob’s Cee‑Lo, Erykah Badu, Gangsta Boo, and B‑Real, bridging the realms of soul, funk, and rock. Yet OutKast never cedes control; their sonic vision remains cohesive despite varied collaborators. The cultural impact extends beyond music. The album cover—André shirtless with arms outstretched, Big Boi in a baggy t‑shirt, both standing against a drooping black‑and‑white American flag—became iconic. It signaled a reimagining of patriotism through a Black futurist lens. André described Stankonia as a place where one could be free to express anything; the album invites listeners into that imaginary space. Even if certain fans are split on the music, Stankonia remains celebrated as a masterpiece, partly because it captured the last time André and Big Boi’s visions fully connected.

As crazy as it sounds, Stankonia still sounds radical. Its triple‑entendre lyrics and bold metaphors remain fresh; its genre‑blending production prefigured the multi‑hyphenate artists of today. While other early‑2000s hip‑hop albums can feel dated, Stankonia anticipates EDM rap, trap, and neo‑psychedelia. It appeals to intellectual nerds and street audiences simultaneously, bridging Afrofuturism with crunk energy. The album’s endurance lies not only in its innovation but in its human core: it is as loud as bombs over Baghdad and as sly as a mumble in the jungle, yet it is anchored by stories of love, struggle, and freedom. Stankonia lets funk be their compass—to imagine new worlds while never forgetting where they come from.

Standout (★★★★½)