Milestones: Tha Carter II by Lil Wayne

Tha Carter II remains a monument in his catalog and a milestone in 21st-century hip-hop—the moment Dwayne Carter, Jr. definitively stepped into the spotlight as a generational great.

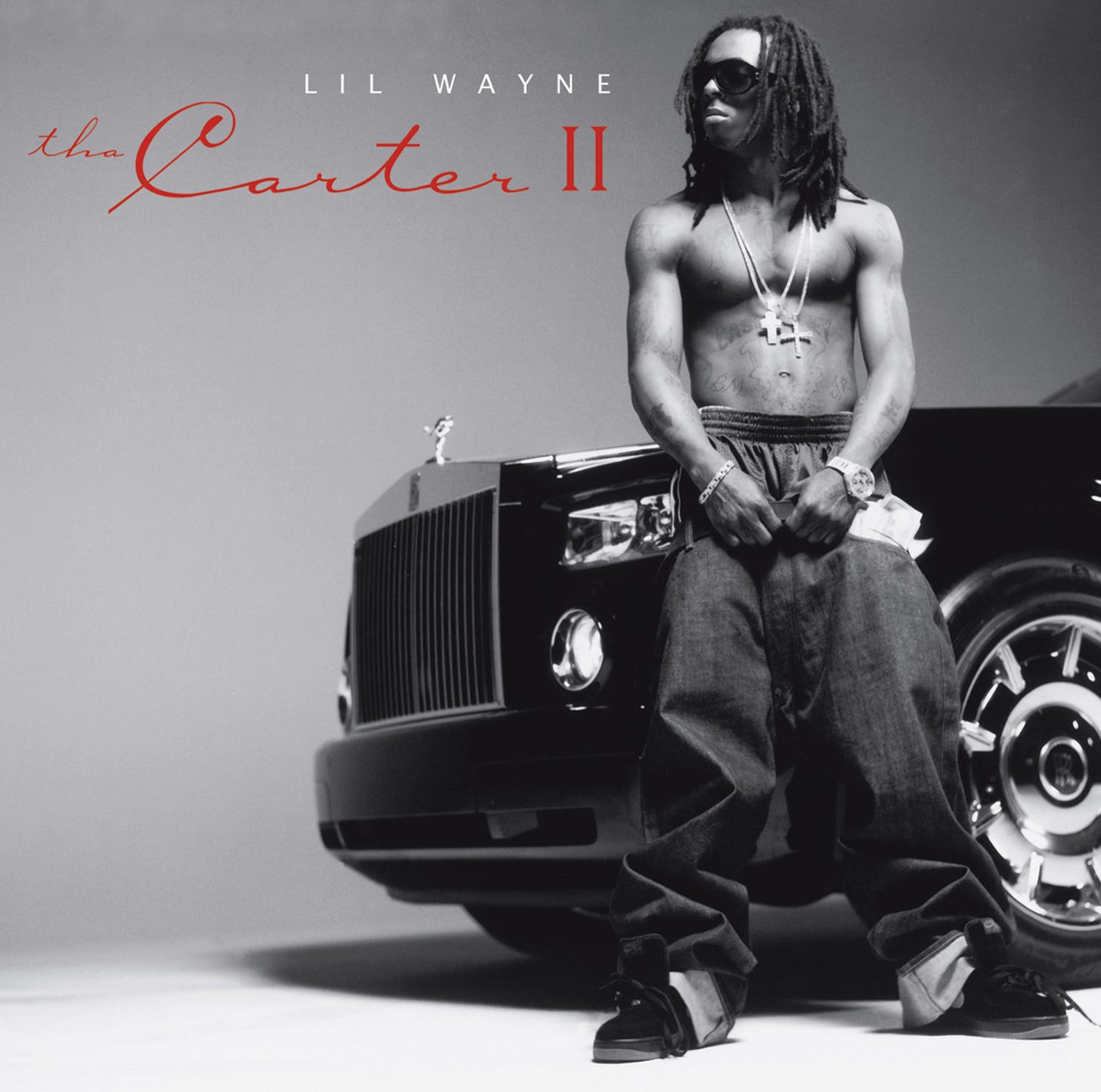

From the cover art onward, a black-and-white image of a shirtless Lil Wayne leaning against a Rolls-Royce, it was clear that this project marked a new chapter. Gone were the cartoonish flames and bling of earlier albums; in their place stood a confident young man poising himself as an adult artist. That confidence wasn’t just visual. On Tha Carter II, Lil Wayne transformed from a promising Hot Boys alumnus into a fully formed rap powerhouse, balancing raw street aggression with polished musicality in a way that would solidify his claim to being the “Best Rapper Alive.”

Released at a critical moment, Tha Carter II built boldly on the foundations of its 2004 predecessor in both attitude and artistry. If Tha Carter showed Wayne shedding his child-star image and finding his voice, Tha Carter II was the album where that voice reached full strength. Wayne was no longer merely cocky—he was truly confident, rhyming with a looseness and daring that yielded that perfect cross between hustler cool and comic timing. His flow and pen game had sharpened since hits like “Go DJ” from the first Carter. His youthful squeak had matured into a gravelly croak, and his once-simple punchlines evolved into complex, free-associative wordplay. It was as if the gloves had come off; Wayne rapped like he had nothing to prove to anyone but himself, which paradoxically proved to everyone that he was a force to be reckoned with.

One of the most striking aspects of Tha Carter II is how it balances hard-edged, freestyle-feeling tracks with smoother, radio-ready singles. Lil Wayne himself seemed to recognize the duality he needed to master—underground credibility and mainstream appeal—and the album achieves both. On one end of the spectrum are the hookless, “freestyle-ish” tracks that feel like Wayne off-the-leash in the booth. The album’s epic opener “Tha Mobb” is a prime example: five minutes of uninterrupted bars, no chorus in sight, just Wayne viciously planting his flag. Over a Heatmakerz-produced beat driven by thumping bass and soulful samples, Wayne proclaims “Cash Money, Young Money, motherfuck the other side,” immediately letting listeners know where his loyalty lies and how high his ambitions reach. The sheer ferocity of his delivery on “Tha Mobb”—“I’m here, motherfucker, make room!” as he snaps in the opening seconds—signals that he’s hungry and gunning for the top spot. This track (much like “Fly In” and its counterpart “Fly Out,” which bookend the album’s two halves) has a mixtape-like grit; it’s the sound of a rapper who doesn’t need a pop formula to entertain. Throughout the album, Wayne sprinkles these no-hook barrages (“Tha Mobb,” “Fly In/Fly Out,” “Best Rapper Alive”) that showcase pure lyrical athleticism and recall the “gutter” aesthetic of his Hot Boys days.

On the other end of that spectrum are the slicker, more melodic songs that court radio. Tha Carter II offers a handful of these “club singles,” but even here Wayne does things his own way. The lead single, “Fireman,” for instance, was a certified banger lighting up request lines in late 2005. Over a stomping Southern beat (all brass and bombast, echoing the anthemic style of classic Cash Money hits), Wayne unleashes fiery boasts and even sneaks in a cheeky punchline—“I’m hot but the car cool/She’s wet, that’s a carpool”—reminding everyone that serious rap can still be fun. “Fireman” cemented Wayne’s image as a human torch of hip-hop, a rapper so ablaze with energy that he threatens to burn up any track he touches.

Yet it’s the other singles and radio-friendly tracks on Tha Carter II that truly showcase Wayne’s evolution. “Hustler Musik,” “Grown Man,” and “Get Over” are all imbued with a smooth, soulful R&B undercurrent that wasn’t present in Wayne’s earlier hits. Instead of slapping on a token R&B chorus in hopes of airplay, these songs have soul woven into their very fabric. “Hustler Musik,” in particular, stands out as an introspective anthem. It rides a mellow guitar-laced groove crafted by in-house producers T-Mix & Batman, and finds Wayne crooning as much as rapping, delivering one of the most heartfelt performances of his career. Over the lush backdrop, his verses bleed together street ambition and emotional vulnerability, making “Hustler Musik” a track that’s as reflective as it is infectious. Many fans consider it the quintessential Lil Wayne song—a smooth, contemplative hustler’s ballad that captures the many facets of his persona. Even years later, Wayne himself has noted its enduring resonance, and some have argued that none of his later singles quite top the soul and sincerity of “Hustler Musik.”

“Grown Man,” featuring young New Orleans protégé Curren$y on a velvety hook, follows a similar template: mid-tempo drums, warm Rhodes piano chords, and a laid-back Wayne reflecting on love and maturity. It’s a decidedly adult song, the kind of suave rap tune you could almost two-step to, and it underlines Wayne’s willingness to step outside hardcore posturing and embrace a more suave, R&B-inflected sound. “Get Over,” produced by Miami duo Cool & Dre, flips a vintage soul sample into a lush backdrop, complete with a female vocal refrain. Wayne rides this beat with a breezy confidence, proving he can glide over grown-folks music just as effortlessly as he snaps on a street banger. Notably, despite their radio-ready sheen, these tracks weren’t even released as singles. It’s just how deep the album’s bench of strong songs was.

One hallmark of Lil Wayne’s style that truly flowered on Tha Carter II is his outrageous sense of humor and inventive wordplay—what one might call his scatological wit. Perhaps no track exemplifies this better than “Money on My Mind.” On the surface, it’s a standard-issue hustler’s anthem about Wayne’s relentless paper chase, but Wayne injects it with a zany, almost gleeful vulgarity that’s unmistakably his. Over blaring horn stabs and trunk-rattling drums (courtesy of Florida producers The Runners and DJ Nasty & LVM), Wayne unleashes one of his most famously filthy punchlines: “Dear Mr. Toilet: I’m the shit.” This absurd, self-aggrandizing couplet—followed by “Got these other haters pissed ’cause my toilet paper thick,” manages to be juvenile and brilliantly boastful at once. It’s arguably one of the wildest ways to call yourself rich that anyone’s ever thought of. Such potty-mouthed whimsy might make your average listener do a double-take, but it perfectly describes Wayne’s brand of raunchy cleverness (which ended up being his weakness in the long term, starting with I Am Not a Human Being).

Perhaps the most significant change on Tha Carter II was behind the boards. This album was Lil Wayne’s first without a single beat from Mannie Fresh, Cash Money’s in-house super-producer who had crafted the entirety of Tha Carter I and virtually all of Wayne’s earlier hits. Fresh’s absence could have been a handicap—his playful, synth-laden “bounce” sound was integral to the Cash Money identity—but instead it became Tha Carter II’s secret weapon. Freed from the comfort of his mentor’s production, Wayne spread his wings and embraced a broad array of sonic styles. The album’s production roster was essentially an ensemble of fresh perspectives: some seasoned, some up-and-coming, many of them hailing from outside the usual Cash Money orbit. Rather than try to re-create the old formula, Wayne and Cash Money’s founders (Birdman and Slim) tapped into a mosaic of sounds that pushed Wayne into new territory.

To fill Mannie Fresh’s shoes, The Heatmakerz—a New York production duo known for soulful sped-up samples in their work with Dipset—were called in and set the album’s tone with “Tha Mobb.” They draped the intro in triumphant horns and vintage soul loops, providing a gritty East Coast-flavored canvas for Wayne’s Southern flow. The synergy was electric, and Wayne sounds utterly at home over the Heatmakerz’ crackling backdrop. (They later also contribute “Receipt,” flipping an Isley Brothers sample into a sultry slow-burner, showing the duo’s range and Wayne’s adaptability.) Cash Money’s own in-house engineers T-Mix & Batman handle a bulk of the album’s tracks, crafting everything from the eerie, piano-plinking menace of “Lock and Load” (a duet with West Coast vet Kurupt) to the sublime bounce of “Grown Man” and the heavy knock of “Hustler Musik.” Their beats have a definite Southern slap but also a glossy sheen, bridging the gap between the old Cash Money sound and something new. Then there are the curveballs, courtesy of a few wildcard contributors.

A young producer nicknamed Yonny (Ronald “Young Yonny” Ferebee) gives “Mo Fire” its distinctive flavor, looping a reggae dancehall bounce under Wayne’s verses. The track literally smokes—it’s built around a slow, skanking groove and toking sound effects, with Wayne adopting a patois-inflected flow as he raps about weed and women. “Mo Fire” stands as one of Tha Carter II’s most adventurous cuts, bringing a Caribbean heat that nods to New Orleans’ own reggae influences and Wayne’s love of experimentation. Another surprise comes from Robin Thicke—yes, the R&B singer (and son of actor Alan Thicke) who at the time was an unexpected name to see on a rap album. Thicke co-produces and sings on “Shooter,” which is actually a reimagining of a song from his own catalog. Over slinky live instrumentation—a bluesy guitar lick, crisp snares, and Thicke’s falsetto crooning the hook—Wayne delivers brash verses that sit somewhere between a rock song and a funk jam. With its genre-blending vibe and a Gang Starr sample tucked in for good measure, “Shooter” is arguably one of the most stylish and adventurous songs Lil Wayne has recorded to date.

Over 78 minutes, Tha Carter II has no shortage of highlights, but a few tracks merit special mention for their lyrical or conceptual brilliance. We’ve covered “Tha Mobb” as a statement of purpose—it’s often lauded as one of the great album intros in hip-hop, and justifiably so. Not only does Wayne spit with ferocity, but his wordplay and internal rhymes on that track announced that a new lyricist had truly arrived. He packs in street wisdom, braggadocio, and homage to New Orleans all in one go, referencing everything from his Uptown roots to his ambition to take over the rap game. By the time he coolly declares “Best rapper alive” on a later track of the same name, it doesn’t come off as hyperbole—Tha Carter II practically shows him earning that title in real-time.

Just a few months before the album’s December 2005 release, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, flooding the city and scattering its residents. Wayne’s own neighborhood, the 17th Ward’s Hollygrove, was hit hard. Though Wayne had been splitting time in Miami and was physically safe, the calamity weighed heavily on him. On the track “Feel Me,” tucked near the end of the album, he addresses the disaster bluntly: in one line, he directs anger at FEMA’s slow response (a “FEMA diss” in rap form). There’s a bitterness and sorrow when he references the state of his city—it lasts just a bar or two, but it’s a rare moment of topical urgency from an artist who usually preferred wordplay over politics. Given recording timelines, most of Tha Carter II was likely completed before Katrina, so the album isn’t a commentary on the storm’s aftermath. But symbolically, Tha Carter II stands as proof that Lil Wayne could weather cultural upheaval just as he was weathering personal and professional ones. The disaster underscored how much had changed since his Hot Boys youth—New Orleans was in crisis, and its prodigal son was now rising to global stardom, carrying his city’s spirit with him.

Equally pivotal was Wayne’s position within his record label. Around the time he was crafting Tha Carter II, Lil Wayne was famously appointed President of Cash Money Records, a bold move by founders Birdman and Slim to entrust their young star with greater leadership. In practice, the title might have been honorary (Birdman still oversaw much of the business), but symbolically, it mattered. Cash Money’s roster had thinned drastically by then—Juvenile, B.G., and Turk (Wayne’s fellow Hot Boys) had all departed, and even Mannie Fresh would leave during this period. Wayne was truly carrying the label on his back, the last man standing from the original Cash Money era, now also the face of its future. Tha Carter II reflects that weight and that freedom. On the one hand, he had all of Cash Money’s resources and focus aimed at him—this was his shot to prove the label wasn’t a spent force. On the other hand, without his old crew and mentor around, Wayne had room to craft an album entirely in his vision. Birdman and Slim essentially “bet the farm” on Wayne’s talent, and Wayne delivered in kind.

This was also a time when hip-hop’s throne was relatively unoccupied—JAY-Z had retired (temporarily), and Eminem was on hiatus around 2004-2005, leaving a vacuum for a new “best rapper alive” to arrive. Wayne audaciously claimed that title, and through Tha Carter II, he made a compelling case for it—at least in the future. After this album, Wayne exploded into a mixtape monster and cultural phenomenon, releasing Dedication 2 and Da Drought 3, which would further cement his Best Rapper Alive claims. One can draw a line from the lyrical onslaught on this project to the dizzying wordplay on those mixtapes. Tha Carter II proved Wayne’s capacity for sustained lyrical brilliance, giving him the confidence to experiment even more wildly on unofficial releases.

When Tha Carter III arrived in 2008 and turned Wayne into a bona fide pop star, it was riding the momentum and artistic growth that Carter II kick-started. And let’s not forget, Wayne’s approach—the fearless mixing of the hardcore and the accessible, the rockstar attitude with a rapper’s dedication to craft—became a blueprint for many who followed. Without Tha Carter II, would there be the same Mr. Degrassi or Sicki Facade (artists Wayne nurtured who similarly blend genres and modes)? Wayne’s influence on the next generation is immeasurable. You hear echoes of his witty, free-associative punchlines in countless rappers today, from the metaphorical play of Kendrick Lamar’s verses to the irreverent flexes of younger Southern artists. In the years that followed, Wayne would hit astronomical highs (multi-platinum success, Grammy awards, cultural ubiquity) and also face lows (record label battles, personal struggles), but the skill, resilience, and audacity he displayed carried him through it all.

The fact that the album was released twenty years ago today is an experience of a turning point in hip-hop. The album stands tall as a classic that captured an artist on the cusp of legend, bridging the gritty Southern rap of the early 2000s with the more expansive, genre-blending direction the culture would take in the years after. For all its fire and bravado, Tha Carter II also has a certain sincerity—the sound of a young man pouring everything into his craft, determined to prove himself. That sincerity, coupled with Wayne’s inimitable talent, is why the album remains his high-caliber peak. However, his albums since the 2010s have progressively worsened, and unfortunately, he hasn’t reached those heights in quality since. Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter II remains a monument in his catalog and a milestone in 21st-century hip-hop—the moment Dwayne Carter, Jr. definitively stepped out of any shadow (be it his forebears or a hurricane’s) and into the spotlight as a generational great.

Standout (★★★★½)