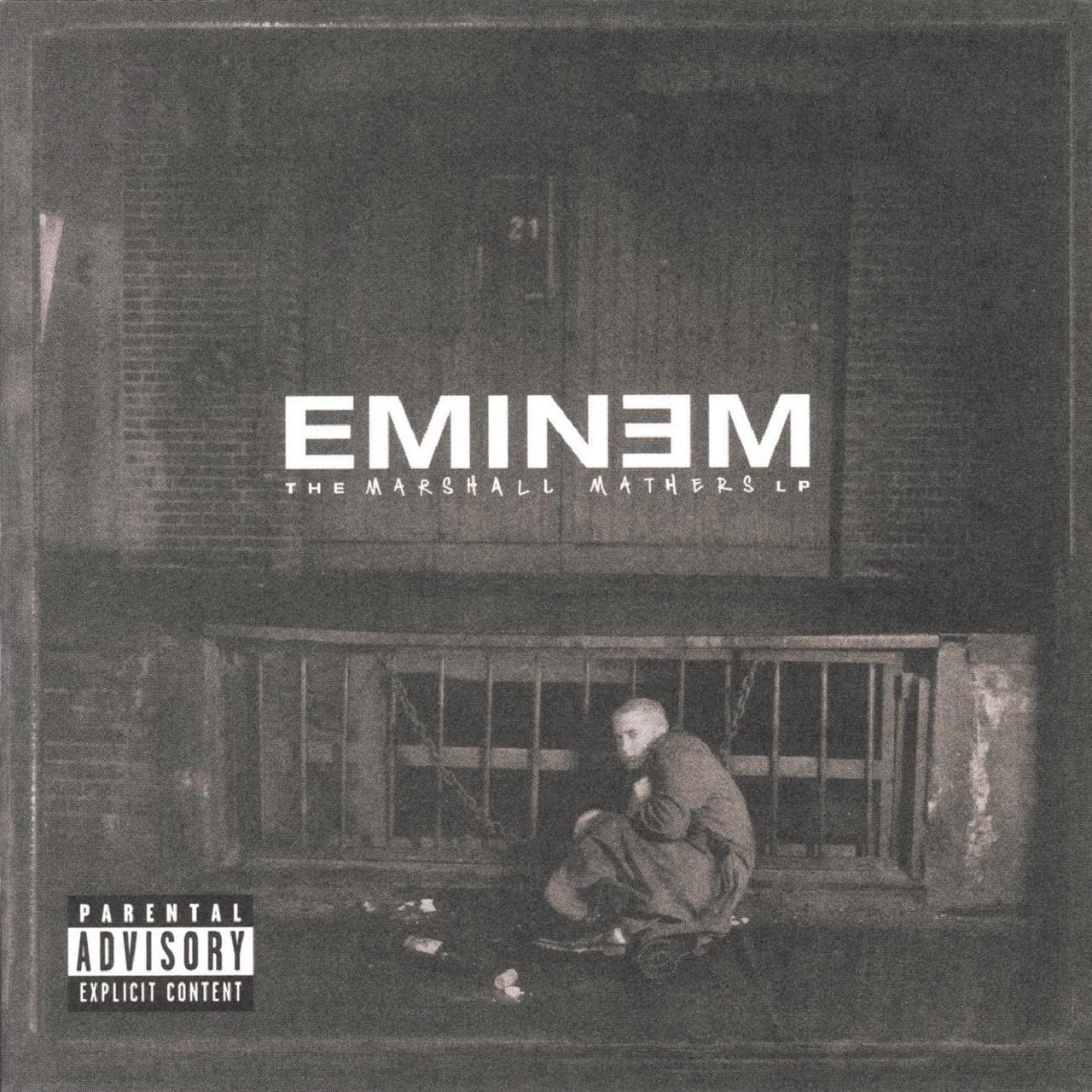

Milestones: The Marshall Mathers LP by Eminem

Eminem forged a body of work that is once a standard and an ethical Rorschach—impossible to separate from the harms it dramatizes, impossible to ignore for the virtuosity with which it is delivered.

Eminem’s ascent from Detroit’s cinder-block clubs to the center of global pop culture happened with frightening speed, and it left the industry scrambling to redraw boundaries that had long separated rap’s core audience from the wider mainstream. When The Marshall Mathers LP arrived in May 2000—only fourteen months after The Slim Shady LP had introduced his sneering alter-ego—its 1.76-million-copy first-week haul shattered every solo-artist sales record then on the books and confirmed that the decade’s most unrepentant wordsmith was also its hottest pop property. That commercial eruption mattered because it rewrote the racial arithmetic of the genre. For the first time, a single white MC, without the cushion of a crossover band like the Beastie Boys or novelty cachet like Vanilla Ice, had planted himself at the commercial summit and held it for weeks.

Two decades later, Dr. Dre would remind the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame audience that labels had once dismissed the very idea of a white rapper on his roster, only to watch the partnership transform the sound of the early 2000s. In that sense, Eminem’s breakthrough is inseparable from an ongoing conversation about American music’s racial gatekeeping: his arrival illuminated how whiteness could both complicate and accelerate access to radio, retail, and relentless coverage, even as his skill set was too prodigious to be reduced to demographics alone.

That rise began in the battle pits of Detroit’s Hip Hop Shop and was accelerated by a second-place finish at the 1997 Rap Olympics in Los Angeles, where a battered demo reached Interscope’s Dean Geistlinger and, within days, Dr. Dre’s desk. Dre’s decision to ignore cautious colleagues who warned him that America would not embrace a white rapper became the hinge on which modern commercial rap swung; within twelve months “My Name Is” had placed the Slim Shady character on daytime MTV and The Slim Shady LP was scanning half a million copies in two weeks. Yet commercial momentum alone cannot explain the velocity of what followed.

What distinguished Marshall Mathers was the way he applied techniques usually reserved for underground cypher circuits—dense multisyllabic rhyme chains, knotted internal rhyme, compulsive assonance—to songs built for radio rotation. Linguists like Adam Bradley have pointed out that the verses on “The Way I Am” place as many as nine assonant vowel hits inside a single bar, an almost unheard-of compression in mainstream rap at the time. Fans who might have bristled at the cartoon violence found themselves quoting schemes whose rigor rivaled Rakim’s and GZA’s. Skill was the Trojan horse; once the drawbridge was down, the outrages came pouring through.

The Marshall Mathers LP is a study in ferocious craft harnessed to nihilistic spectacle. Recorded in the pressure cooker of sudden fame, its production kept Dre’s clean low-end but surrendered the glossy surfaces that had softened The Slim Shady LP; Eminem’s own minor-key loops allowed him to sound both claustrophobic and gargantuan, boxing himself in only to tear the walls down. “Kim” rewrote the domestic-murder fantasy as Grand Guignol, while “Stan” inverted fan mail into gothic tragedy, feeding Dido’s spectral hook through cascading internal rhymes that stacked with the elegance of a sonneteer who hates himself for caring.

The record’s language was radioactive even by rap’s desensitized standards. GLAAD denounced its homophobic slurs; women’s groups condemned scenes of dismemberment; and the Guardian ran a Sunday essay labeling the album “the most blatantly offensive homophobic work we have ever heard.” Yet the friction between verbal orchestration and moral provocation only intensified the public’s fixation: Columbia University scholars later noted how the album’s rhetoric of violent caricature courted—and thrived on—outrage, forcing audiences to ask whether authorial intent could ever be disentangled from social consequence.

“Public Service Announcement 2000” opens the record with an almost-throwaway half-minute that is anything but filler: over Jeff Bass’s circus-organ flourish, Slim Shady interrupts the broadcast to promise “we would like to take this time to tell you kids not to do drugs.” It is the first misdirection, a wink that the next seventy minutes will satirize every moral panic aimed at rap, and because it is placed before any full song, it positions the album as media critique before it is autobiography. The gag works because the voice is faux-official; the government tone sets up a cheap moral, only for “Kill You” to smash through the wall nineteen seconds later. That bait-and-switch is the album’s structural tic. Two skits—“Paul” and “Steve Berman”—repeat the trick, but with real names attached.

“Kill You” is the album’s most relentlessly quoted indictment in Senate hearings and newspaper op-eds, partly because its horror-core theater arrives before the listener has time to calibrate nuance. Lynne Cheney held up the lyrics—“Slut, you think I won’t choke no whore till the vocal cords don’t work in her throat no more?”—as proof that the industry profited from gendered violence. However, the track’s technical choices are often skipped in moral hand-wringing. Dre programs sub-bass kicks so dry they resemble muffled gunshots, while Em threads triple-rhymed end words across four-bar phrases, turning the flow into a runaway flywheel. The dissonance between baroque rhyme play and grind-house subject matter is the very point. The uglier the fantasy, the prettier the structure, daring listeners to decide which sensation wins.

When the album does pause to breathe, it does so with gallows humor. “Marshall Mathers” rides a languid Dre bass line while Em dismantles pop-star etiquette: “I was put here to put fear in f****t-to-dope queer/And Britney Spears to switch me chairs…” Here, the rhyme bursts aren’t incidental ornament; they function as percussion, filling gaps the drum machine refuses to occupy. He flips the same trick on “Amityville,” where Bizarre’s grotesque satire merges with Mathers’s comic timing, and on “Remember Me?” where Sticky Fingaz’s sandpaper rasp forces Em to accelerate his cadence just to stay in the pocket. Each guest verse becomes a stress test for his own, and he answers by threading jokes through breathless triple-times, proof that agility can coexist with crudity.

“Drug Ballad” arrives like a guilty exhale. The tempo loosens and Dina Rae croons “Back when Mark Wahlberg was Marky Mark” while Em, for once, lets the rhyme scheme lounge in half-notes. It’s a hazy reminiscence rather than a confession, yet even the nostalgia is destabilized by internal slippage: “I’m the type to wake up naked next to Freddy Krueger…” slurs into “I’m wasted” before the bar ends, as though the narrator can’t even keep his syntax upright. The track’s woozy swing underlines a seldom-credited side of Mathers—his instinct for groove. Listen to how his consonants soften on every snare, dragging behind the beat like a drunk who knows exactly where the curb is but keeps tripping anyway.

If hip-hop history often measures legitimacy by co-sign, then “Bitch Please II” is the song that suffocated the argument. Snoop Dogg delivers the opening drawl, Dre drops the glue-snare mix he once reserved for “Still D.R.E.,” and Eminem walks in on the third verse rhyming like a human Dictionary as though English were begging to stretch for him. For the Dre camp, it stamped Mathers as peer, not novelty; for skeptics, it closed whatever daylight remained between color and craft. Album sequencing matters here. “Criminal” closes the record with a burlesque organ loop and an explicit disclaimer—“If I offended you, you ain’t gotta listen to my music”—then spends the next five minutes offending everyone possible.

Taken song by song, The Marshall Mathers LP reads less like a single provocation than a collection of short films bound by a director’s unflinching eye. However, some individuals who accused the album of relying too heavily on technique were only half right. The method doesn’t hide the ugliness so much as force us to stare at it longer, because the ear stays to admire what the gut wants to flee. Beyond that, nowhere did that tension feel more visible than at the 2000 MTV Video Music Awards, where Eminem marched up Sixth Avenue trailed by more than a hundred peroxide-blond doppelgängers in white T-shirts, a living echo of the chorus line mocked in “The Real Slim Shady.” The stunt worked as pop meta-theater as an artist accused of warping young listeners’ literalized the fear by flooding Radio City Music Hall with his own replicas, then pivoted into a barked rendition of “The Way I Am” that recoiled from the very circus he had just created.

The contradictions only harden under cultural scrutiny. Protesters outside the 43rd Grammys held placards quoting “Kill You,” yet inside the venue, Elton John sang the author’s most empathetic ballad, collapsing the binary of villain and ally with one arm-around-the-shoulder hug. A year earlier, a phalanx of peroxide clones had followed him into Radio City Music Hall, and parents gasped while teenagers memorized every bar before bedtime. In 2017, the Oxford English Dictionary added “stan” to its lexicon, proof that the LP’s most heartbreaking story had metastasized into everyday slang, a reminder that even cautionary tales can become memes. Meanwhile, academics still cite the record in studies on misogyny in rap, noting that eleven of its fourteen songs deploy derogatory language against women. The numbers can coexist because the art is built on coexistence: tenderness and brutality, empathy and scorn, metrical elegance and vulgar punchline, all compressed into bars tight enough that none of the tensions can escape.

What those bars ultimately did was redraw hip-hop’s center of gravity. Before 2000, a white solo rapper achieving diamond status without novelty framing looked implausible; after The Marshall Mathers LP, crossover gatekeepers recalibrated their expectations, and a generation of MCs—Mac Miller, Logic, Jack Harlow—entered a market whose doors had already been unhinged. The re-scaling came with a cost. Eminem’s presence intensified debates over appropriation, privilege, and the line between persona and prejudice. Yet even detractors concede that his surge forced hip-hop’s critical apparatus to sharpen its vocabulary around flow, breath control, and rhyme density, facets once dismissed as insider metrics. The conversation today, about whether polysyllabic patterns matter more than punch-in authenticity, whether narrative ambition offsets rhetorical harm, traces directly back to the track-by-track machinery of this record.

So, if it ever sounded as though the previous essay lingered too long on the gridwork and not enough on the grooves, the corrective is simple: press play on any individual cut. Forget the sales records; listen instead for the moment in “The Way I Am” when the violins drop out and he has to land a sixteen-bar free-fall with nothing but consonants to break the impact. Or the instant in “Stan” where a seat-belt click becomes a percussive stop-sign before the final plunge. Each flourish confirms what the controversy sometimes obscures: for all the moral static, the album already had its own perfect reception system—headphones on, eyes closed, heart braced for whatever the next bar might do.

Standout (★★★★½)