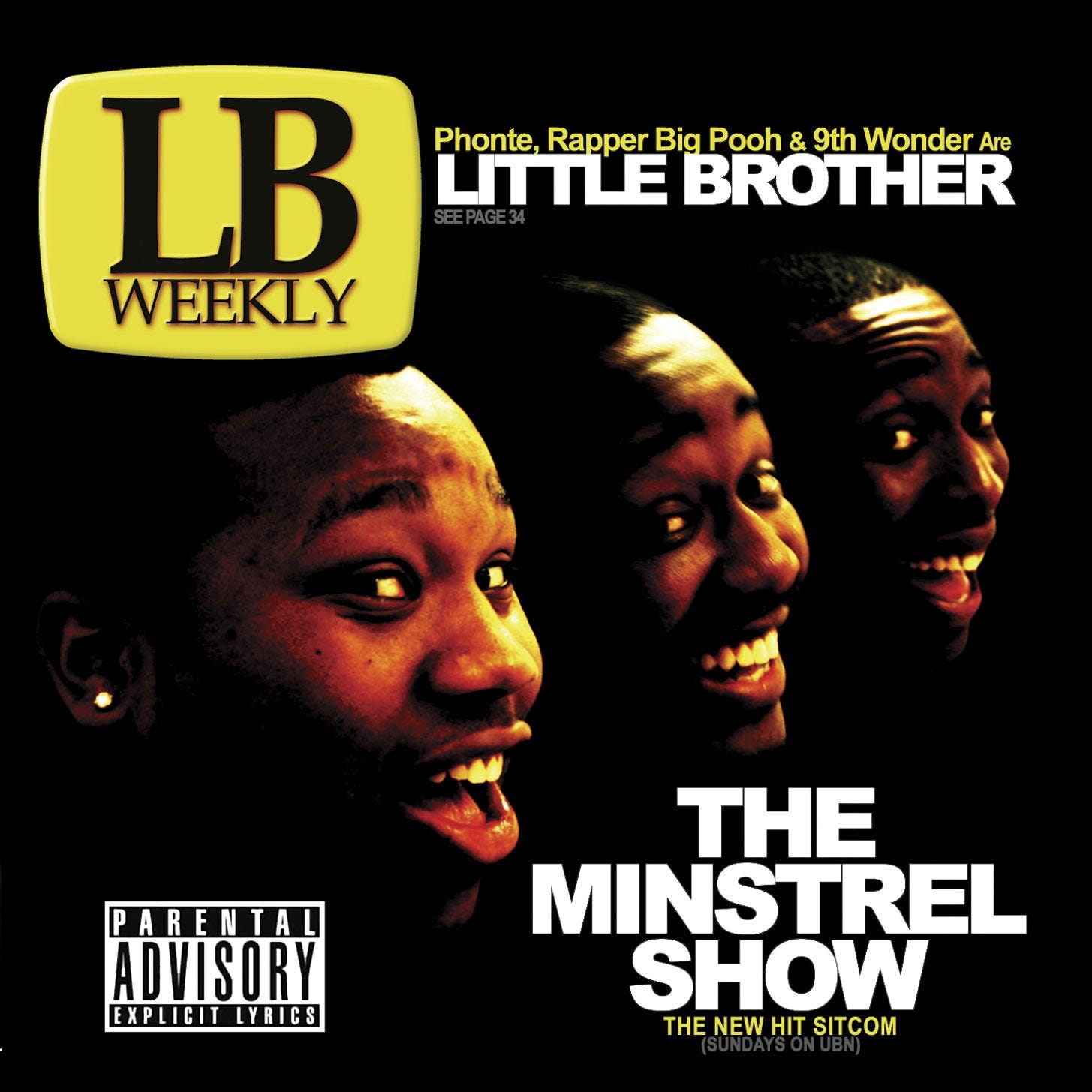

Milestones: The Minstrel Show by Little Brother

As their magnum opus, The Minstrel Show is proof that Little Brother kept faith in their audience and in their artistry, even when the industry around them pulled in another direction.

By the mid-2000s, hip-hop’s underground had become major-label bait. Young emcees who’d built loyal followings on indies now faced pressure to water down their sound for mainstream exposure. Durham, North Carolina’s Little Brother—rappers Phonte Coleman and Thomas “Big Pooh” Jones and producer 9th Wonder—had proven themselves by 2003, releasing The Listening on indie ABB Records to strong notices. They then inked a deal with Atlantic Records, hoping to expand their audience without sacrificing their style. The tension of that transition infuses The Minstrel Show. From the outside, Atlantic’s resources looked like a breakthrough. Behind the scenes, label turnover and creative disagreements were real. A&Rs who signed Little Brother left before the ink was dry, and the group found themselves explaining their vision to new executives. Remarkably, Atlantic allowed Little Brother to make the album largely on their own terms. Phonte later said Atlantic “very much let Little Brother do it their way,” a rarity on a major at the time. He also quipped they chose the provocative title The Minstrel Show because “we couldn’t call it Nigga Music.” The era was a give-and-take: the trio had to prove they could thrive on a major, but the record released to the world was, in Phonte’s words, “the exact record we took out of our computer in Durham.”

Conceptually, The Minstrel Show plays like a day of programming on a fictional network, UBN (“U Black Niggas Network”), complete with theme music, live performances, backstage interludes, and tongue-in-cheek commercials. In this Sunday-morning broadcast, Chris Hardwick introduces the show, and radio DJ Pete Rosenberg voices UBN’s announcer. YahZarah and Darien Brockington appear as gospel singers on the opening “Welcome to the Minstrel Show” intro. Fake ads hawk odd products—“5th & Fashion” sells off-brand Ferragamo loafers and a DVD called Left A-1s—and characters like “Angry Black Dad” rant about self-esteem and math homework. The extended concept is a satire of stereotypical Black-targeted programming and advertising, a playful but pointed homage to Black pop-culture tropes. Even the physical packaging mimicked a TV Guide issue with print ads and a crossword puzzle. In both structure and spirit, the album pays affectionate tribute to variety shows and soul revues while skewering them. Phonte’s R&B alter ego “Percy Miracles” turns up on “Cheatin’,” spoofing melodramatic romantic sagas in the vein of R. Kelly or Ronald Isley. One skit calls it “the biggest colored show on earth,” and Little Brother gleefully pulls every lever of TV satire—from goofy jingles to mock news updates—without losing love for the culture they lampoon.

Sonically, the group stays true to their throwback roots with a fresher shine. 9th Wonder’s soul samples and chopped loops fuel nearly every track, keeping a warm, classic feel while sounding cleaner and more focused than before. The sole outside production is “Watch Me,” handled by Justus League affiliate Khrysis. It rides majestic minor-key piano and closes with a quick scratch cameo from DJ Jazzy Jeff—a small flourish that reads as a nod to the golden era and fits the album’s past-meets-present lens. Elsewhere, 9th toggles from buoyant funk (“Lovin’ It”) to gospel-tinged lift (“Slow It Down”) to lush balladry (“All for You”), polished enough for a major platform without betraying Little Brother’s identity.

As a duo, Phonte and Big Pooh balance playful bravado with unguarded reflection. “Beautiful Morning” sets that tone. Big Pooh opens with a bricklayer’s boast—“Stack them up like bricks, you can call me the mason of shit / Foundation has been rock solid no replacing, ya dig?”—and then shrugs off gray skies with, “even if the birds ain’t singin’ and the sun ain’t shinin’,” it’s still a beautiful morning. Phonte follows by grounding the swagger in cost and commitment: “This is the price that I pay for this music/And every word that I write is a testament to it/And if I had to go back, I wouldn’t change a thing/Wouldn’t re-cut it, re-edit, or change a frame.” Gratitude and sacrifice sit side by side.

The album’s broad-shouldered confidence peaks on “Lovin’ It” and “Say It Again.” Over a horn-happy 9th groove, Phonte bellows, “When I’m on the mic y’all should expect the grandest,” and Pooh adds, “Constant hits keep ’em scrambling ’til the stores, ’til the shelves dismantling.” Even the hook reads like a mission statement: “Don’t stop, can’t stop, yes I love it… East Coast say they lovin’ it.” On “Say It Again,” Pooh pushes the boast to cartoon scale—“I’m overweight, rap is fat to deat /Obese when these beats catch wind of my breath”—then flips to a sideline warning: “Niggaz ain’t ready for damage… y’all niggaz off-sides and gotta extra man.” Phonte takes his turn with “I got so many rhymes, many styles to go with,” and slips the knife on industry nonsense: “I love hip hop, I just hate the niggaz in it.” The tone is confident and wry—victory laps that poke fun at victory laps.

The quiet core lives in “All for You,” a two-part father-son reckoning. Big Pooh’s verse reads like a letter to his absentee dad. He apologizes, admits what the absence did—“his child was scarred”—and asks forgiveness “for yanking your chain.” The voice catches as he confesses, “I give a fuck how he gon’ react,” after years of waiting for a call that never came. Phonte answers from another angle, a new father watching history echo: “I did chores, did bills, and did dirt/But I swear to God I tried to make that shit work/‘Til I came off tour to an empty house/With all the dressers and the cabinets emptied out.” Love curdles into “chains,” the family gone while he was chasing songs. Darien Brockington’s hook stitches the verses into a single ache. The skits keep levity in orbit—“Angry Black Dad,” the 5th & Fashion ad breaks, a sermon-slam in “Hiding Place.” They aren’t throwaways; they hold the concept together and clarify the thesis: the group loves Black culture and refuses to worship its clichés uncritically. The Percy Miracles bit works as both parody and craft, and several characters would reappear on May the Lord Watch, showing how the world-building stuck.

The rollout met turbulence. Before most fans heard a full song, The Source’s mic-system dispute made noise: an editor voted 4.5 out of 5, but ownership allegedly dropped it to 4, and the editor resigned in protest. Phonte later joked that the dust-up drew more attention than a clean 4.5 ever would. Then came BET. Little Brother filmed a bright, house-party video for “Lovin’ It,” but it never aired. Rumors said the clip was “too intelligent” for the network; BET’s PR shrugged that they simply didn’t have to play it. Either way, the album effectively had no visual single on the main TV channel of the moment. The Minstrel Show debuted at No. 56 on the Billboard 200 with about 18,000 sold, then slid. Atlantic moved on, pushing only one official single and no follow-up. Within a year, the partnership ended. 9th Wonder left the group and didn’t tour the album; he would surface across the wider scene while Pooh and Phonte made the next LP, GetBack, as a duo. Meanwhile, the indie-rap conversation shifted to new names.

Commercially, the album fell short of the targets a major label typically expects. Artistically, it became a quiet cornerstone. With distance, you can hear how it anticipated later blends of social commentary, humor, and soulful uplift that would surface in different ways across the next decade. Phonte and Pooh have called Little Brother “ahead of its time,” and the arc reads that way: visionary artists a few steps in front of the market’s understanding. Their reunion LP, May the Lord Watch, tapped the same vein—reusing characters and tones from The Minstrel Show—and confirmed how durable the idea was. The Minstrel Show didn’t become a blockbuster, but it holds up. That’s a big part of why the group remains beloved.

Today, the record is remembered for marrying satire and soul without losing its grin. On “Lovin’ It” and “Say It Again,” they earn the hype with punch-line boasts—“I’m overweight, rap is fat to death,” “constant hits… dismantling the shelves.” On “Beautiful Morning” and “All for You,” they show the weight under the wit: Phonte admits, “I did chores, did bills, and did dirt/But I swear to God I tried to make that shit work,” and Big Pooh pledges to keep the foundation “rock solid.” Industry setbacks may have slowed its rise, but they didn’t blunt its resonance. Fifteen years on, it still feels like “a classic album motherfuckas couldn’t find,” as Phonte put it—and in the long view, it finally found its audience.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)