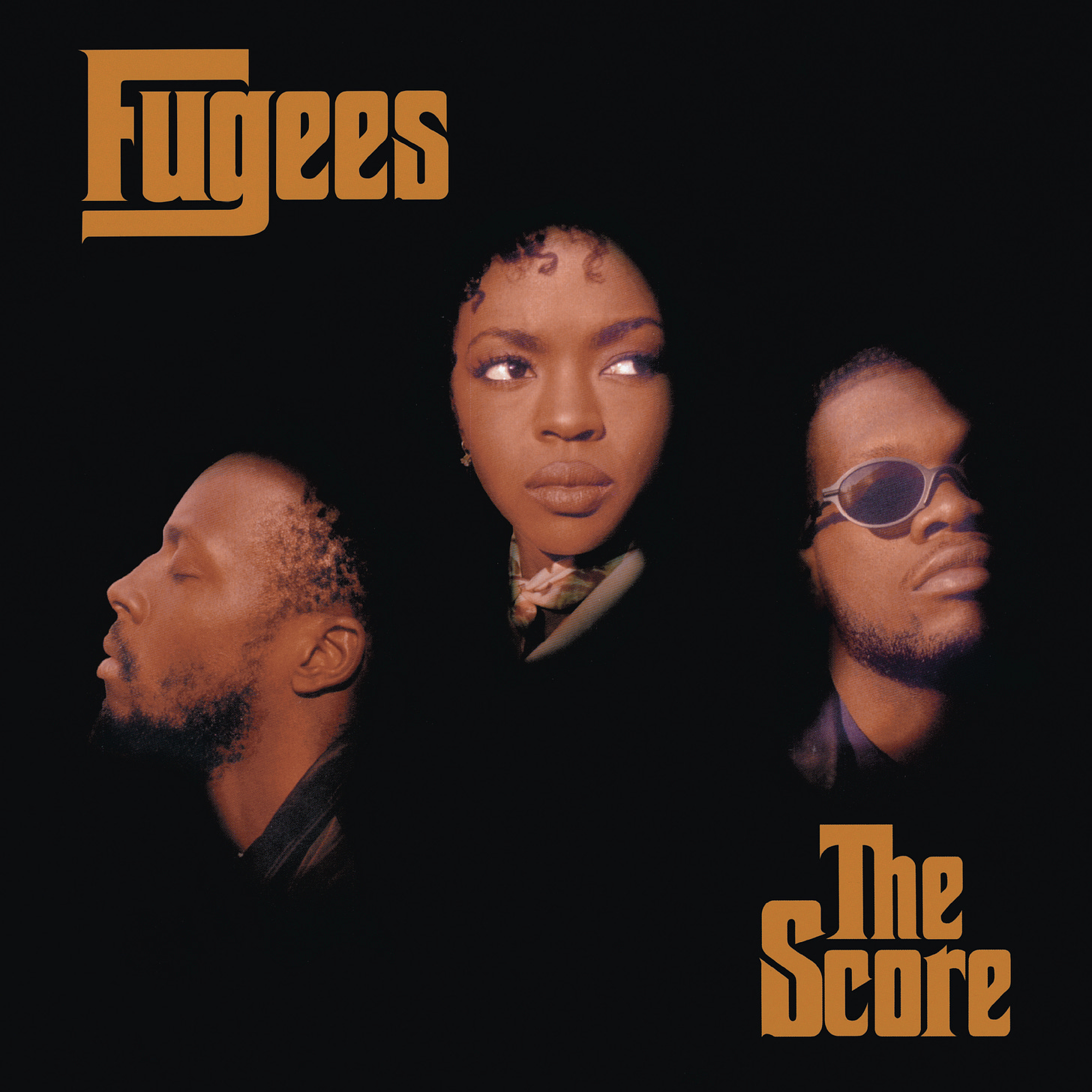

Milestones: The Score by Fugees

How a flopped debut and one Salaam Remi remix bought the Fugees a second chance. The basement sessions that followed changed hip-hop, and then success ripped them apart.

By early 1995, the Fugees were dead in the water. Blunted on Reality had limped onto shelves in January ‘94 and promptly disappeared from everybody’s radar, moving units so slowly that Columbia started eyeing the door. The trio from Jersey—Pras Michel, Wyclef Jean, and a teenage Lauryn Hill—had signed to Ruffhouse with dreams of fusing Caribbean flavor with East Coast grit, but the label’s heavy production hand squeezed the life out of those ambitions. Critics yawned. Radio stations passed. Street cats couldn’t vibe with it. Even the group later admitted they’d surrendered too much creative control and ended up with an album that sounded like somebody else’s idea of what they should be.

Salvation arrived through Salaam Remi’s remix boards. When he stripped down “Nappy Heads” and rebuilt it around a breezy synth line and jazzy bassline, the track finally clicked. That reworked version cracked the Billboard Hot 100 at number 49, proving the Fugees had ears in the streets if somebody would just let them cook their own food. The remix sessions with Remi also yielded an early blueprint for “Fu-Gee-La,” and suddenly Ruffhouse head Chris Schwartz saw enough promise to gamble again. He cut the group a check for $135,000 and handed them something they’d been starving for since day one: complete artistic control.

That bread went straight into equipment. Wyclef’s uncle Jerry “Wonda” Duplessis had a basement at 232 South Clinton Street in East Orange, and the crew converted that modest underground space into their own laboratory. They christened it the Booga Basement, and from June through November of ‘95, three young heads from Jersey set up shop and started building. “The basement wasn’t even like luxurious or a big studio,” John Forté recalled years later. “It was you know just a studio that was heartfelt and earnest…and by that I mean small.” Didn’t matter. Pras and Wyclef crashed there regularly, L-Boogie practically lived there, and soon the basement attracted a rotating cast of visitors who heard something special brewing. Redman might pop in one night, Queen Latifah another, Rah Digga whenever inspiration struck. The Booga Basement turned into the illest sleepover in hip-hop history, cats nodding their heads to beats at three in the morning while the rest of Jersey slept.

Recording proceeded at what Wyclef described as a “relaxed pace.” Nobody breathing down their necks about radio singles or crossover potential. Just three kids from an urban background expressing themselves, making music that felt different from the gangsta posturing and player anthems crowding the airwaves. Hill was twenty years old. Pras had just turned twenty-three. Wyclef, the elder statesman at twenty-five, brought his guitar and his Caribbean ear to sessions that stretched until dawn. “It was done calmly, almost unconsciously,” he told interviewers later. “There wasn’t any pressure—it was like ‘let’s make some music,’ and it just started forming into something amazing.”

Each member occupied a distinct lane. Pras kept his eye on the big picture. He’d been the original architect back at Columbia High in Maplewood, the upperclassman who spotted young Lauryn and wanted to build a group around her presence. On The Score, his executive producer credit meant he was asking the hard questions every session: Is the hook right? Is it strong enough? Will this bang outside the basement? His verses arrive economical and direct, never overstaying their welcome, always making room for his partners to breathe. That selflessness doesn’t get praised enough. Plenty of MCs would’ve fought for more bars on tracks destined for platinum plaques, but Pras understood the group chemistry required restraint.

Wyclef operated as the sonic mad scientist. Haitian roots ran deep in his DNA, and he brought reggae cadences, acoustic guitar flourishes, and an immigrant’s perspective on American contradiction to every recording session. His voice shifts between rapping, singing, and straight-up toasting depending on what the track demands. On “Family Business,” he straps on his guitar and lets the strings do the talking. Throughout the album, his production choices refuse to stay in one stylistic neighborhood. He’d flip the Delfonics and Enya on “Ready or Not,” then pay homage to Bob Marley on the closer. That restlessness kept the record unpredictable even as it cohered around the group’s shared sensibility.

And then there was L-Boogie. Anybody paying attention during those basement sessions knew Lauryn Hill had evolved into something special. She could rap with the aggression of any MC on the come-up, but she could also sing with the church-trained conviction of a Roberta Flack or an Aretha Franklin. That combination barely existed in hip-hop at the time. Female rappers had to choose between being hard or being pretty, between rocking the mic and catching vibes. Lauryn rejected the binary and claimed both territories simultaneously. Her version of “Killing Me Softly” became the album’s signature moment precisely because she refused to treat singing and rapping as separate pursuits. She inhabits the Roberta Flack melody like she owns it, then pivots back into MC mode without missing a breath.

The Score ran on samples and live instrumentation working in tandem. Warren Riker handled engineering alongside Jerry Duplessis, ensuring the basement recordings achieved a warm, spacious quality despite their humble origins. Diamond D contributed beats. John Forté brought his own rhythms and eventually grabbed verses on several tracks. The Outsidaz crew—Rah Digga, Young Zee, and Pacewon—dropped guest verses that kept the cipher rotating. Salaam Remi’s fingerprints remained on “Fu-Gee-La” and other cuts, his remix sensibility helping polish rough diamonds into radio-ready jewels without sacrificing the group’s underground credibility.

February 13, 1996. The Score landed in stores and promptly detonated. The album climbed straight to number one on the Billboard 200 and the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart. “Fu-Gee-La” had already primed the pump, dropping in early January to reintroduce the Fugees as a completely reconfigured unit. Then “Killing Me Softly” arrived and changed the conversation entirely. The cover shot to number one in twenty countries, including five consecutive weeks atop the UK Singles Chart. In America, the track dominated airplay charts even though it technically couldn’t qualify for the Hot 100 under the era’s physical single rules. “Ready or Not” followed as the third single and duplicated that UK chart-topping success, its eerie Enya sample giving the track an otherworldly feel that separated it from anything else bumping that summer.

Within eighteen months, The Score achieved sextuple platinum certification in the States. Grammy voters named it Best Rap Album for 1997, and the Recording Academy also honored “Killing Me Softly” with the trophy for Best R&B Performance by a Duo or Group. The Source included the album on its list of the 100 greatest rap records ever pressed. Worldwide sales eventually topped twenty million copies, an astonishing figure for a sophomore effort from a trio that had been on life support barely two years earlier.

The victory tasted bittersweet. Success breeds opportunity, and opportunity breeds separation. By ‘97, all three members had launched solo ventures. Wyclef dropped The Carnival and established himself as a genre-hopping producer with clients ranging from Canibus to Carlos Santana. Lauryn started cooking what would become The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, a 1998 masterpiece that won five Grammys and sold eight million copies domestically. Pras linked with Mýa and Ol’ Dirty Bastard for “Ghetto Supastar,” a massive soundtrack single that demonstrated he could command the spotlight alone. The Fugees never officially announced a breakup, but another album never materialized. Internal tensions, external demands, romantic entanglements between members—the usual culprits chipped away at the collective until only memories remained.

The aftermath scattered the trio across vastly different trajectories. Lauryn retreated from the industry’s demands and became increasingly elusive, her live performances growing legendary for their unpredictability. Wyclef maintained visibility through production work, humanitarian efforts in Haiti, and that ill-fated 2010 presidential campaign bid in his ancestral homeland. Pras stayed active in documentary filmmaking and music, but his name returned to headlines for grimmer reasons. In April 2023, a federal jury convicted him on ten felony counts related to an illegal foreign influence campaign involving the Malaysian financier Jho Low and the 1MDB scandal. The charges included conspiracy, acting as an unregistered foreign agent, and funneling millions into Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign through straw donors. In November 2025, a judge sentenced him to fourteen years in federal prison and ordered forfeiture of nearly $65 million.

That courtroom ending casts long shadows backward across The Score and its refugee mythology. The album’s title came from Lauryn, who told interviewers she wanted something “powerful and metaphorical” because the group “had a couple of scores to settle” after critics dismissed their debut. Settling scores with doubters is one thing. The federal charges against Pras suggest he eventually tried settling scores of a different sort entirely, courting billionaires and political power brokers in schemes that would’ve bewildered the twenty-three-year-old kid making music in his cousin’s uncle’s basement.

None of that diminishes what the album actually captured when those three young voices committed their perspectives to tape in East Orange during 1995. The Score documented a particular moment when hip-hop could still accommodate crews who refused to pick a single lane. The Fugees never fit neatly into the gangsta category, and backpack purists couldn’t entirely claim them either. Their politics ran subtler than Public Enemy or KRS-One, yet they never ducked substance for party records. They occupied a crowded middle ground where Caribbean heritage, Haitian immigrant experience, New Jersey street knowledge, and crossover ambition could coexist without anybody accusing them of selling out or going soft.

“How Hard Is It” rides a stripped-down loop while Wyclef and Lauryn trade verses about the grind of survival in a system designed to crush dreams. “The Beast” confronts the prison-industrial complex with the fury of three people who’d watched friends and family vanish into the system. When Pras declares “Can’t even trust the court appointed lawyer/Mad man gonna be bored to death,” he’s spitting from genuine frustration with a justice apparatus that warehouses Black and brown bodies. “Fu-Gee-La” celebrates persistence and self-determination. “Where your keys/Where your deeds/Where your G’s at/Refugee camp,” Wyclef demands, turning the immigrant slur into a badge of defiant pride. The group reclaims “refugee” and flips it into an identity worth celebrating rather than a stigma requiring apology.

“Killing Me Softly” outgrows its origins as a Roberta Flack cover by becoming a statement about recognition and artistic kinship. When Lauryn sings about a stranger performing her life in song, she’s describing the vulnerability every honest artist feels when they hear somebody else articulate their interior world. That universality explains why the record crossed every demographic barrier radio programmers could erect. “Ready or Not” channels paranoia into propulsion, its sample of Enya’s “Boadicea” creating an atmosphere of creeping menace that suited the mid-‘90s mood of hip-hop fans who’d just lost Tupac and Biggie to real-world violence. “Zealots” loops a Flamingos sample into soul-stirring commentary on spiritual conviction. The record closes with a gorgeous take on Bob Marley’s “No Woman, No Cry” that honors Jamaica while acknowledging the Fugees’ own American roots.

Does any of it still matter three decades later? The twenty million copies suggest it mattered plenty to listeners seeking hip-hop that didn’t demand they choose between intelligence and enjoyment. The Grammy wins signaled the industry recognized something significant had occurred. Lauryn Hill’s subsequent solo triumph confirmed that The Score wasn’t a fluke but a launchpad for generational talent. The album’s inclusion on countless greatest-of lists ensures new generations will encounter its lessons about creative autonomy and cross-cultural fusion.

Whether the music itself holds weight for future generations depends on whether they still need reminders that hip-hop can synthesize influences without abandoning its roots. “Cowboys,” “Vocab,” and “Family Business” remain textbooks on group dynamics and microphone rotation. “The Mask” shows that earnest social commentary doesn’t require lecturing your audience into boredom. Every beat Wyclef and Pras constructed in that basement testified that modest budgets and cramped quarters can’t constrain imagination if the artists refuse to accept limitation.

The Score settled scores with everyone who dismissed the Fugees after their debut stumbled. Then it raised the stakes for everyone who came afterward, proving that a trio of Jersey kids with Caribbean blood and street credentials could build something that resonated from Maplewood to Manila. The basement studio became a transitional house for young Haitian refugees after the group disbanded. Some scores, it turns out, stay settled.

Masterpiece (★★★★★)