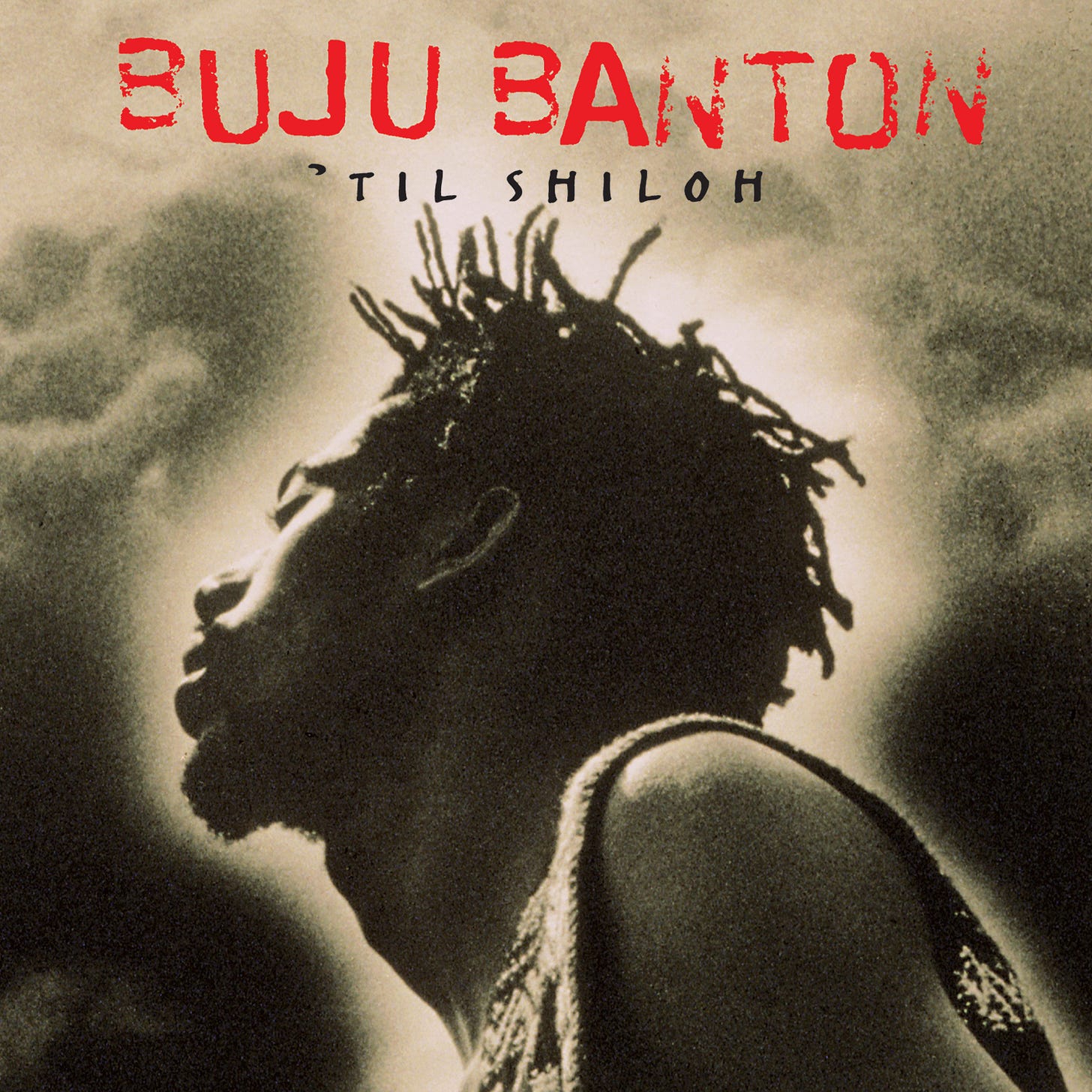

Milestones: ‘Til Shiloh by Buju Banton

‘Til Shiloh signaled a dramatic transformation in dancehall, blending spiritual roots reggae with the hard-edged energy of '90s Jamaican sound system culture.

In the mid-1990s, Jamaica’s musical landscape was dominated by the thunderous booms of dancehall. Sound systems rattled street corners with slack lyrics and “gunman” anthems, and a young deejay named Buju Banton stood at the forefront of this scene. By 1994, Buju was dancehall’s reigning star, a 22-year-old with a gravelly, thunderous voice and a string of hits laced with raw sexuality and machismo. He had even shattered Bob Marley’s record for the most chart-topping singles in Jamaica in a year. Yet amid the heights of his “rude bwoy” fame, Buju found himself searching for something deeper. Scandals had already tested him, most infamously the homophobic shock of “Boom Bye Bye” (written in his teens), which brought international protest and nearly derailed his career. The time was ripe for a rebirth. As dancehall reached its peak, a wave of neo-Rasta consciousness was also swelling in Jamaica—a return to roots and spirituality led by artists such as Tony Rebel, Garnett Silk, and Luciano. Buju Banton stood at a crossroads between the two Jamaicas: the “slack” dancehall of gun talk and the reverent tradition of Rastafari. His landmark ‘Til Shiloh album, released in July 1995, became the bridge between these worlds.

By pressing play, ‘Til Shiloh announces that a new Buju Banton has arrived. The album opens not with a bass drop or a catchy hook, but with a brief a cappella invocation: “Strangest feeling I’m feeling/But Jah love we will always believe in/Though you may think my faith is in vain/‘Til Shiloh, we chant Rastafari’s name.” For 18 seconds, Buju’s familiar rough-edged voice is unaccompanied, rising from a hushed murmur to a fervent chant that sounds like a prayer. In those lines, essentially a one-man choir chanting the name of Jah (God) and Rastafari, Buju firmly plants his flag in spiritual soil. The setting evoked is not a crowded dancehall at 2 AM, but a wooden church chancel; his deep voice beseeches inward and skyward at once, carrying the cadence of gospel even as it invokes Rastafari over Christianity. For an audience accustomed to Buju’s booming braggadocio, this intro felt jarring and mesmerizing. Buju Banton, the notorious champion of slack dancehall, was embracing a new role as a Rastafarian messenger. The very title ‘Til Shiloh hints at this mission, a Jamaican phrase meaning “forever” or until the next Messiah comes. Buju was telegraphing that from here on out, he would chant Rastafari’s name forever, come what may.

If the opening invocation posed a question—What sort of album might follow such a prayer?—the next track, “‘Til I’m Laid to Rest,” delivered a definitive answer. It begins with wordless, wailing harmonies reminiscent of Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s African gospel tones, then drops into the heartbeat thump of Nyabinghi hand drums. Buju intones, half-singing, half-deejaying: “Oh, I’m in bondage, living is a mess/I’ve got to rise up, alleviate the stress/No longer will I expose my weakness/He who seeks knowledge begins with humbleness.” The once-cocksure “Stamina Daddy” now openly speaks of bondage and weakness, countering them with upliftment and humility. It’s as if Buju is testifying, admitting the pain of “living in Babylon” and vowing to seek enlightenment. Musically, the effect is electrifying.

Buju Banton’s spiritual awakening was not just a musical gimmick; it was rooted in real personal change. In the years leading up to ‘Til Shiloh, Buju had begun growing out his dreadlocks, studying the teachings of Haile Selassie I, and communing with elders about his African ancestry. He learned that his lineage traced back to Maroons, Jamaica’s escaped slaves who fought colonial power, deepening his sense of mission and identity. This personal journey from dancehall badman to Rasta sage can be felt throughout the album. In interviews, Buju described ‘Til Shiloh as a turning point that marked his transformation “from a dancehall hardcore DJ to one who espouses views on global political social issues,” embracing his Black identity “as a Rastaman and an African.” He viewed the album as part of a calling to “re-educate the masses” about Rastafari culture beyond the stereotypes, noting that many people wear dreadlocks for style but “don’t understand the teachings.”

The album did not abandon the grit of real-life Kingston—instead, it grounded its spirituality in the hard truths of Jamaica’s streets. Take “Murderer,” one of the album’s most haunting tracks. Over a somber bassline and siren-like keys, Buju addresses the cycle of violence plaguing his community. A real tragedy inspired the song with the murders of fellow dancehall artists Panhead and Dirtsman, gunned down in late 1993/94. Buju’s voice seethes with grief and controlled fury as he calls out the perpetrators and the system that enables them. “Murderer! Blood is on your shoulders,” he chants, simultaneously a condemnation and a warning. According to Buju, the track was also a direct “callout to Jamaica’s corrupt government” and the impunity of gunmen who got off scot-free. This was a startling turn for an artist who, just a couple of years prior, had flirted with glorifying gun culture. The communal shock of losing fellow musicians had clearly galvanized Buju’s conscience.

On the flip side of that confrontation is “Champion,” the album’s most famous dancehall anthem. Built on a driving, instantly infectious riddim, “Champion” gave Buju a massive hit and ensured that ‘Til Shiloh would rule the dance floors as much as the spiritual retreats. At first blush, “Champion” seems like a throwback to Buju’s braggadocious past— it’s a triumphant boast track, declaring “I’m a champion, no boy can test!”—and indeed the song’s punchy drums and taunting hook made it a sound system staple for years. Yet in the context of the album, even “Champion” takes on a richer meaning. It’s as if Buju is redefining victory and strength on his terms. The “champion” in Buju’s new vision is not just the dancehall don, but the soul that overcomes hardship and remains true. Placed alongside somber songs like “Murderer” and uplifting pleas like “Untold Stories,” “Champion” feels like a moment of redemption—a burst of joy and confidence that celebrates the power of survival and faith. And by including such a crowd-pleasing banger on a rootsy album, Buju proved that embracing spirituality didn’t mean forfeiting his status as dancehall’s reigning entertainer.

Nowhere is Buju Banton’s duality more moving than on “Untold Stories.” This track has often been called Buju’s “Redemption Song,” and for good reason. Stripped to an acoustic guitar and light percussion, “Untold Stories” finds Buju forsaking the deejay chatter entirely to sing a poignant folk ballad. The gentle strum and melody immediately evoke Bob Marley’s classic acoustic laments, or even the stark honesty of a Tracy Chapman ballad. Buju’s delivery here is a revelation: his voice, usually so rough, turns tender, cracking at the edges as he pours out a searing testimonial of ghetto life. “It’s a competitive world for low-budget people, spending a dime while earning a nickel,” he sings plaintively, sketching the impossible economics faced by the poor. He speaks of hungry youths and despairing mothers, and asks why equal rights and justice still elude the sufferahs. In crafting this song, Buju applied the exact intricate rhythmic timing of his dancehall art to an “emotionally raw subject”, achieving an immediacy that feels like someone baring their soul on a street corner. “Who can afford to run will run, but what about those who can’t? They will have to stay,” he cries, giving voice to the voiceless.

For all its heavy themes, ‘Til Shiloh is far from one-note. Buju and his collaborators were careful to balance the album’s mood, interweaving hard-hitting reality tunes with moments of uplift and even romance. After testifying on the stand of “Untold Stories,” Buju flips the script with “Wanna Be Loved,” a sweet lovers rock-flavored hit. Over a mellow groove, Buju croons his desire for genuine love and acceptance, showing that even a devout Rasta can flirt and sing a soulful love song, “Rastas could flirt just as passionately as they prayed to Jah,” as one writer quipped. “It’s All Over” and “Only Man” bring back a touch of the playful dancehall vibe, the latter riding the popular “Arab Attack” riddim, reminding listeners that Buju hasn’t lost his mischievous charm. These lighter tracks don’t feel out of place; instead, they highlight ‘Til Shiloh’s carefully curated journey. Just as a reggae sound system set might intersperse conscious tunes with party songs to keep the crowd engaged, Buju’s album sequences spiritual and secular themes in conversation with each other.

The impact of ‘Til Shiloh was immediate and enduring. In Jamaica, the album’s success marked a sea change in dancehall culture. Many of Buju’s contemporaries soon followed his lead towards “conscious” lyrics and Rastafarian themes. Artists such as Capleton, Dennis Brown, Garnett Silk, Anthony B, and Sizzla began infusing their music with the same blend of digital fire and roots spirituality, accelerating what became known as the neo-roots movement. Veteran deejays who had built careers on pure slackness found themselves increasingly out of step; indeed, observers noted that after ‘Til Shiloh’s release, few of the old dancehall badmen (Shabba Ranks, Ninjaman, Cutty Ranks, etc.) scored any major hits—the center of gravity had shifted. Buju’s album had expanded the possibilities of what dancehall could be: it proved that drum machines and synthesized riddims could coexist with Nyabinghi drums and acoustic guitars, and that a deejay famed for gun talk could dedicate an album to prayer, social commentary, and personal growth without losing his edge.

Producer Donovan Germain and the team behind ‘Til Shiloh carefully crafted this sonic fusion, and its influence was soon evident on seminal late-90s records like Sizzla’s Black Woman & Child (1997), Luciano’s Sweep Over My Soul (1999), and Capleton’s More Fire (2000)—all of which took the idea of a holistic, album-oriented dancehall statement to heart. Beyond Jamaica, ‘Til Shiloh sent ripples through the global music scene. The Fugees’ blend of hip-hop and reggae in the mid-90s had a similar spirit, but it’s telling that when Ms. Lauryn Hill set out to craft her magnum opus The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998), one of her most powerful tracks, “To Zion,” unfolded like a neo-roots reggae hymn straight out of Buju’s playbook. With its gentle guitar, loping Rasta rhythm, and spiritual invocation of God’s guidance for her son, “To Zion” echoed the template Buju perfected—personal testimony over acoustic reggae soul. It was a sign that ’Til Shiloh’s legacy had traveled far: from Kingston’s Trenchtown to American R&B/hip-hop, the idea of merging the personal, the political, and the spiritual in music had found new adherents.

As the years have passed, ‘Til Shiloh has only grown in stature. A quarter-century on, it’s routinely cited as one of reggae’s classic albums, and in 2020 it was officially certified Gold, underscoring its ongoing popularity. But statistics alone can’t capture its legacy. More important is how Buju Banton’s full emergence on ‘Til Shiloh as the self-declared “Voice of Jamaica” still resonates today. Buju earned that moniker (which he’d boldly used as an album title in 1993) by fearlessly channeling the joys and pains of the Jamaican people in his music. On ‘Til Shiloh, he truly became that voice—empathetic, unfiltered, and unbowed.

In the words of reggae historians Kevin Chang and Wayne Chen, “many critics saw Buju’s 1995 album ’Til Shiloh as the genre’s first masterpiece.” It was a masterpiece born not just of musical innovation, but of personal conviction. Buju showed that an artist at the height of fame could fundamentally reinvent himself and, in doing so, help shift his whole genre’s course. That courage—to offend the powerful in defense of the powerless, to risk backlash for speaking truth—gives ‘Til Shiloh a timeless fire. “You will get some backlash for calling out the powerful… but that’s good backlash. You’re offending the right people,” one of Buju’s colleagues observed of his evolution. Buju Banton understood by 1995 that his voice could be a weapon or a balm—could harm or heal—and he chose the path of healing.

Standout (★★★★½)

one of the most formative albums of my youth ❤️