Milestones: Voodoo by D’Angelo

D’Angelo released one of the holy grails in music to kick off the new millennium. After his debut LP and writer’s block dilemma, Voodoo inspired so many babies that R&B artists still leech off today.

The thing about writer’s block is this: You want so desperately to write something, but that’s not how songs come about. Songs are brought to you by life itself. You have to live in order to write. Ask an expert. If anyone understands writer’s block, it’s surely Michael Eugene Archer.

In 1995, with his debut album Brown Sugar, the man known to the music world by his stage name D’Angelo laid the foundation for the up-and-coming neo-soul genre. His blend of soul, funk, and R&B—shaped by a deeply rooted understanding of what makes hip-hop unique—cultivates the same soil that Tony! Toni! Toné! and Me’Shell Ndegeocello had already tilled, and where the careers of Maxwell, Omar, and Erykah Badu would soon sprout and reap a bountiful harvest.

D’Angelo himself does pretty well—reviews of Brown Sugar range from kind to downright exuberant. The album sells brilliantly. The promotional tour lasts two full years. By then, in the fast-paced music business, impatience starts to grow. Isn’t it time for a follow-up? Shouldn’t he be getting on with it…? But the muse cannot be rushed. She kisses whomever she pleases, whenever she pleases—not necessarily when it suits the record company’s schedule.

D’Angelo has little choice but to accept his fate. Eventually, he gives up his strained attempts at writing, smokes a bit, half-heartedly lifts some weights, and otherwise waits for inspiration. Of course, the idea of completely renouncing music is unthinkable for someone who has played piano and various other instruments since early childhood. D’Angelo punctuates his creative break with featured appearances that sometimes end up on multiple soundtracks, and he collaborates with artists like Erykah Badu and Ms. Lauryn Hill, appearing on her album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

As he later recalls, the starting gun for the second phase of his artistic career is fired by life itself. A new life, to be precise: the birth of his first son ends the deep slumber of the songwriter within him. Suddenly, the flames burn brightly again.

Still weighed down by the violent deaths of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls, D’Angelo goes searching for clues to his musical identity. He travels through the American South, tracking his musical heritage in South Carolina. “I got sucked into a real undertow,” he remembers later. “I swam in gospel, blues, a flood of old soul, early James Brown, very early Sly and The Family Stone, and plenty of Jimi Hendrix. I learned a lot—about music, about myself, and about which direction I wanted to move in musically.”

He can’t make peace with the current state of R&B: “R&B doesn’t mean what it used to,” he sneers. “R&B is pop—that’s the proper term for it. Contemporary R&B is a joke, and the funny thing is that the people making this shit take it dead seriously. It’s sad: they’ve reduced Black music to nothing but a club thing.”

D’Angelo refuses to jump on that bandwagon. Shortly after the release of his live album Live at the Jazz Café in 1998, he set his sights—this time with absolute determination—on his second album. The modest goal was to create a new sound that represents the logical, natural evolution of the work his musical heroes began.

Of course, that first requires studying them—studying them thoroughly. Music journalist Touré, who writes for Rolling Stone, among others, describes the recording sessions from which Voodoo would emerge as D’Angelo’s “years at soul university, complete with lessons, silly pranks, rumors, and about equal parts discipline and utter laziness.” D’Angelo holes up with his cohorts in New York’s Electric Lady Studios, built once upon a time by Jimi Hendrix—yes, him again.

The albums created simultaneously there paint a picture of the all-encompassing creative atmosphere: Common works on Like Water for Chocolate, Erykah Badu on Mama’s Gun. Meanwhile, Q-Tip, Talib Kweli, and Yasiin Bey drop in, as do Eric Clapton, Rick Rubin, and comedian Chris Rock. After a quick check—“Who’s here today?”—spontaneous collaborations spring up constantly.

A common vibe runs through the albums by Common, Badu, and D’Angelo, a vibe that’s nearly impossible to resist. Tonal engineer Russell Elevado is largely responsible, with his love for live instruments, analog equipment, and old-school recording techniques, giving all three records a similar underlying mood.

D’Angelo’s sessions bring together the absolute cream of the crop of studio musicians available in R&B, jazz, and hip-hop at the time. The ever-present bass is ruled by Pino Palladino—except in “The Root,” “Greatdayndamornin’,” and “Spanish Joint,” where Charlie Hunter handles all the strings (both guitar and bass). Roy Hargrove plays flugelhorn on “Spanish Joint.” The multi–Grammy-winning James Poyser plays keys. Raphael Saadiq is involved in the songwriting of “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” and DJ Premier provides the programming for “Devil’s Pie.” In the form of Method Man and Redman, hip-hop’s infernal duo makes a guest appearance on “Left & Right.”

At the center of this creative whirlwind stands Roots drummer Ahmir ‘Questlove’ Thompson, whom D’Angelo calls his “co-pilot.” Together, they set a course for new horizons—by looking far back into the past. They spend hours, days, and weeks watching music videos and live concert footage of their idols, as well as old episodes of Soul Train.

They devote enormous amounts of time and energy to playing through classic albums, note for note, from start to finish. From these sessions, new sounds and melodies emerge naturally. “One night, they were playing Prince’s Parade,” recalls Touré, who was there to witness it. “At some point, they drifted off into a new groove that later became ‘Africa.’”

Voodoo is literally rooted in its predecessors. Everyone D’Angelo reveres collectively as his “Yodas” has left their mark: Al Green, Fela Kuti, George Clinton, Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye. Stevie Wonder (the organ he used on Talking Book had already been hauled into the studio by Elevado), Prince, J Dilla, and Sly & The Family Stone’s 1971 classic There’s a Riot Goin’ On, and always Jimi Hendrix. “I’m convinced he was there,” D’Angelo says of the studio atmosphere. “Jimi, Marvin Gaye, all those guys we worshipped. I think they blessed this project.”

They must have blessed it generously. With Voodoo—the title itself a reference to Black tradition and myth, dark and powerful—D’Angelo, singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and producer, delivers one of the finest modern R&B albums. If not the very best, then certainly, it’s a pure funk record filled with the purest soul. One thing leads to another; each genre grows from what came before. Blues, jazz, funk, soul, hip-hop, and ambient blend so organically that the development of Black music flashes before your inner eye like a film.

“I have the utmost respect for the masters who came before me,” D’Angelo explains in an interview with Ebony. “I feel a certain responsibility to distill the essence of their work and carry it forward into my time and my generation.” Voodoo fulfills that mission perfectly, even if its creator later regards the album only as a first step in the right direction: “My inspiration is to keep moving, to reach the next level… I’m still evolving the sound in my head, letting it grow—and I’m listening.”

The lengthy and unorthodox recording process is reflected in the structure of Voodoo. The tracks have a jam-session character; none run less than four and a half minutes. Naturally, the label’s decision-makers eye this with mixed feelings. They would have much preferred traditional three-minute hits for mainstream radio, something Brown Sugar had in abundance.

The first three singles from the long-awaited follow-up—the overtly critical “Devil’s Pie,” the highly explicit bedroom jam “Left & Right,” and “Untitled (How Does It Feel)”—sell only moderately, none climbing high in the charts. To recoup their investment, the marketing strategists push an expensive promo campaign with ads, interviews, and videos.

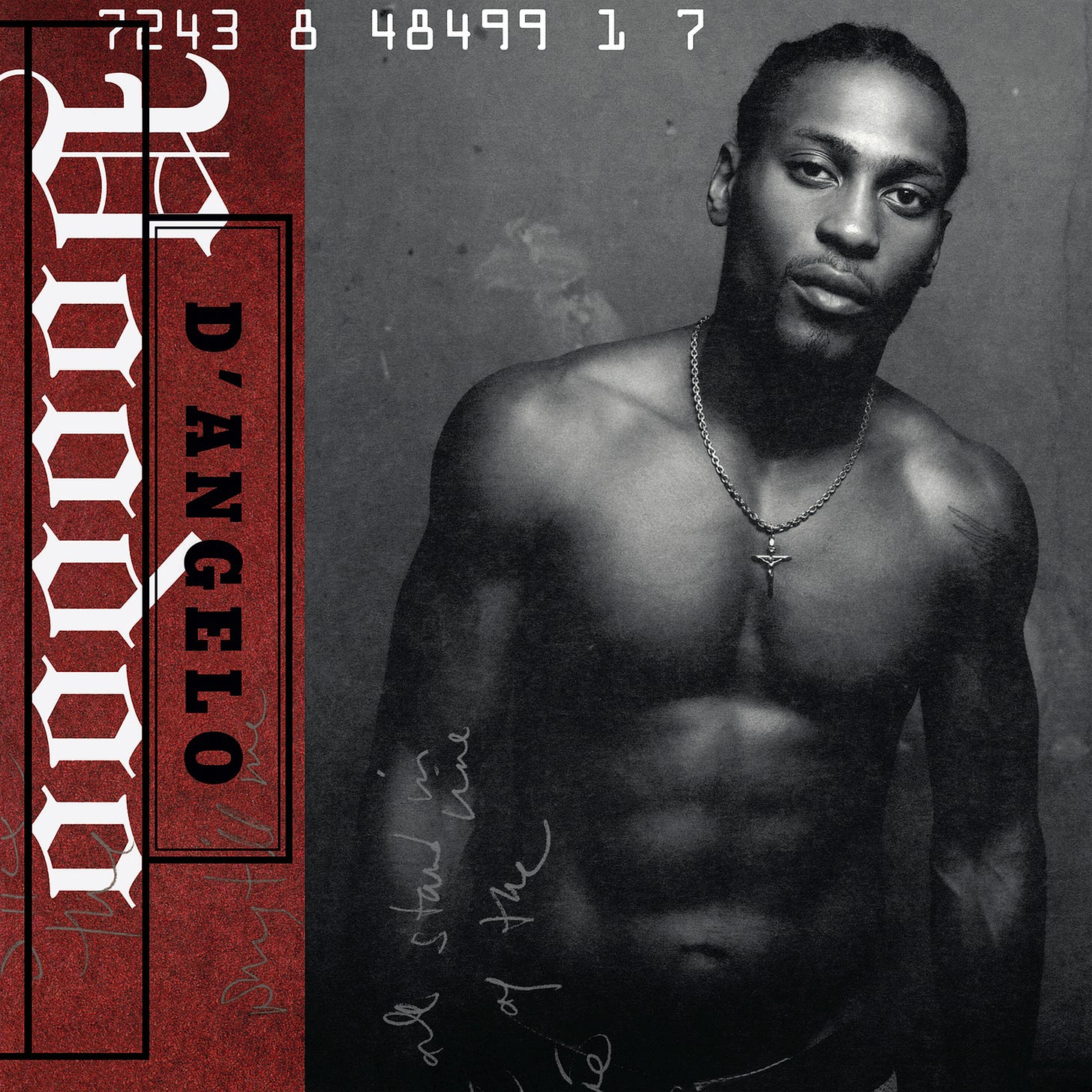

The turning point comes with the video Paul Hunter directs for “Untitled.” And how! It shows D’Angelo naked, gleaming with sweat, singing his heart out—from the hips up, anyway, but not much imagination is needed to envision the rest. This video changes everything—not entirely to D’Angelo’s advantage, as we will see. It elevates the singer to sex-symbol status while simultaneously reducing the artist to a mere pin-up.

First and foremost, the look of “Untitled” provides an impressive testimonial to Mark Jenkins. Hired by D’Angelo—who had let himself go a bit during his long hiatus—as a fitness trainer, Jenkins, nicknamed the “Drill Sergeant” by D’Angelo’s musician friends, earns his stripes: three hours a day, he relentlessly puts his client through the paces. The results are clearly visible.

Still, if you look closely at the “Untitled” video, you can tell D’Angelo isn’t entirely comfortable in such an exposed pose. “You have to realize he’d never looked like that before,” Jenkins told Spin years later. “A guy who was extremely introverted, suddenly three or four months later, he’s literally naked—it all happened so fast.” Far too fast to gauge the far-reaching consequences.

Even without the video, the track exudes pure sex—everything that makes sex great: total surrender, passion, utter ecstasy. Some critics call the track “the best Prince ballad Prince never wrote.” Saul Williams, who wrote the Voodoo liner notes, finds it amusing: “I would have paid good money to see the look on Prince’s face when he heard this album.” D’Angelo considers the song a tribute to one of his greatest idols.

Voodoo finally appears on January 25, 2000—after multiple postponements—enters the charts at number one, and knocks Santana’s Supernatural off the top spot. In the first week alone, 320,000 copies are sold. It remains on the Billboard charts for a solid 33 weeks. The eight-month “Voodoo Tour” becomes a victory lap—at least in the beginning.

Then the pendulum swings back. The mainstream audience now floods the concerts, appetite whetted by the “Untitled” video. Instead of caring about his music, these fans are far more interested in glimpsing the chiseled physique of the man music critic Robert Christgau has since dubbed “the R&B Jesus.”

D’Angelo grows increasingly frustrated by the constant cries of “Take it off! Take it off!” and the accompanying disregard for his artistic achievement. “He got pissed,” Questlove recalls, having witnessed the tour from behind the drums as leader of the backing band The Soultronics. “The crowd thought: ‘Fuck your art—we wanna see your ass!’ It made him angry.”

Questlove sees another cause for the problem: “Everyone’s insecure,” he explains. “But his insecurity reached a point where sometimes I thought I should quit playing drums and just be his cheerleader. Some nights on tour, he’d stare into the mirror and say, ‘I don’t look like I did in the video!’ That was all he could think about. Sometimes, we’d have to wait an hour and a half to start the show until he felt mentally or physically ready. Some shows didn’t happen at all. But that was just a pretext. Deep down, he was thinking: ‘They don’t get it. They just don’t get it. They only want me to strip.’”

“I think if he had known what ‘Untitled’ would lead to, he wouldn’t have done the video,” Questlove concludes. But time can’t be reversed. Somehow, everyone manages to bring the Voodoo tour to a close.

What we’ve heard from D’Angelo since then has been sporadic and mostly unfortunate. Alcohol and drugs have taken their toll. He’s had multiple run-ins with the law, including illegal weapons possession and driving under the influence—one incident nearly cost him his life. He’s entered rehab more than once. His relationship fell apart; he lost contact with his family. In 2010, he spent a brief stint in jail for offering $40 to an undercover cop for a blow job.

Rumors of a planned follow-up to Voodoo pop up again and again. D’Angelo’s attempt to play not just most but all of the instruments himself—for total creative control—has presumably not sped up the process. The label eventually lost patience and cut off his funding.

D’Angelo announced a new album first in 2009, then in 2010. A year later, Questlove, supposedly involved in its creation, claimed the work was “97 percent done.” In early 2013, he upped that to “99 percent” in an interview with Billboard. As of May 2014, the latest word is that two videos have surfaced from recent studio sessions.

The absence of a follow-up only feeds the legend of Voodoo up until we get Black Messiah out of nowhere in December 2014. “I’m like that old bucket of Crisco sitting on top of the stove,” D’Angelo once said, summing up his achievement of blending all his predecessors’ flavors to create his own, unique taste. The NME puts it just as aptly: “This album represents nothing less than African-American music at a crossroads. Calling D’Angelo’s work straight-up neo-soul doesn’t do it justice—it leaves too many elements off the table: Vaudeville jazz, Memphis horns, ragtime, blues, funk, bass grooves, not to mention the hip-hop that flows from every pore of these 13 songs that take hold of you.”

Whether he employs basketball metaphors in “Playa Playa,” denounces materialism in “Devil’s Pie,” explains the “Chicken Grease,” laments a lost love in “One Mo’ Gin,” covers Roberta Flack’s 1974 hit “Feel Like Makin’ Love,” or, as in “Africa,” cradles his son in a gentle lullaby tracing the Black diaspora back to the motherland, D’Angelo always puts his bleeding heart and entire soul on the line.

Voodoo earns him and Russell Elevado a Grammy for Best R&B Album and the singer another for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance. Time Magazine declares it the best album of 2000. It sounds like the record Marvin Gaye or Curtis Mayfield might have made had they survived to see the new millennium. The omnipresent groove burrows under your skin and sends chills through your body—emanating from within.

“I think he’s a genius, and I don’t have the words to describe it,” says Questlove, who otherwise never lacks for vocabulary. “But then I ask myself how I can go around calling someone a genius when there’s barely any work to prove it. Then I remind myself that the little he has recorded is so powerful it lasts for ten years.” Those ten years, however, have long since passed.

It seems writer’s block continues to hold the musician in a stranglehold—perhaps fueled by the nagging fear D’Angelo once admitted in an interview. When confronted with the fact that 98 percent of his musical heroes ended up failing, burned out, or dead, he quietly responded: “That’s exactly what I think about all the time.”

Masterpiece (★★★★★)