“Not Just Hip-Hop”—The Hidden Hierarchy Within

Does this language elevate or erase hip-hop’s value? What does it say about respect, legacy, genre hierarchy—and who gets to define “artist”?

The declaration “I’m not a hip-hop artist” has become a recurring refrain in contemporary music, but it’s never just about genre. In a New York Times Popcast interview on August 15, 2025, ahead of his country album release, BigXThaPlug stated: “I’m not just a hip-hop artist—I want to be the best artist in the world. The only way I can do that is if I can show that I can do something other than rap.” Although the clip went viral earlier last week, the implication is unmistakable: being confined to hip-hop means not being the best, that artistic legitimacy requires transcending rap.

He doubled down in multiple interviews that month. In a Billboard video, he compared himself to Beyoncé, arguing that real artists can’t be “held in one lane” before adding: “It’s the difference between a rapper and an artist.” In a MusicRow interview on his album release day, he declared, “I’m an artist. I might go pop after this—you never know. But I want to be the best artist I can possibly be. And to do that, you’ve gotta conquer different levels.”

The language reveals a hierarchy. The rapper sits at the bottom, the artist at the top. Hip-hop is presented as a limitation to escape rather than an art form to master. Yet BigX’s genre exploration was built entirely on the foundation of his hip-hop success—he used the culture as a launching pad, then positioned himself above it. Perhaps most tellingly, months earlier in February 2024, BigX had confessed to Billboard: “Sometimes I catch myself like, ‘Why are you still rapping? You know you not a rapper.’” This internal doubt about being a rapper—not about his skills, but about the label itself—reveals the internalized hierarchy where “rapper” carries stigma that “artist” doesn’t. And lord behold, he decided to work with Post Malone on “Cold” for his deluxe version of his Country-laden project, I Hope You’re Happy.

Speaking of his culture vulture self, Post Malone’s comments were more explicitly dismissive. In a November 2017 interview with Polish media outlet NewOnce, he stated: “If you’re looking for lyrics, if you’re looking to cry, if you’re looking to think about life, don’t listen to hip-hop.” He elaborated: “There’s great hip-hop songs where they talk about life and they spit that real shit, but right now, there’s not a lot of people talking about real shit.” This statement came after Post had built his entire career on hip-hop aesthetics, production, and collaborations. “White Iverson” and “Rockstar” were unmistakably hip-hop tracks that launched him to stardom. Yet here he was, characterizing the genre as shallow and devoid of meaning—this about a genre with a rich tradition of social commentary from Public Enemy to Kendrick Lamar.

The backlash was immediate. Earl Sweatshirt, Complex, The Root, and AFROPUNK all called out the statement as disrespectful cultural appropriation. Post issued a video apology three days later, blaming alcohol and claiming he was misunderstood (we call bullshit), but he doubled down on parts of his critique: “What I was trying to say is that a lot of people, except for a handful of artists, are saying the same shit.”

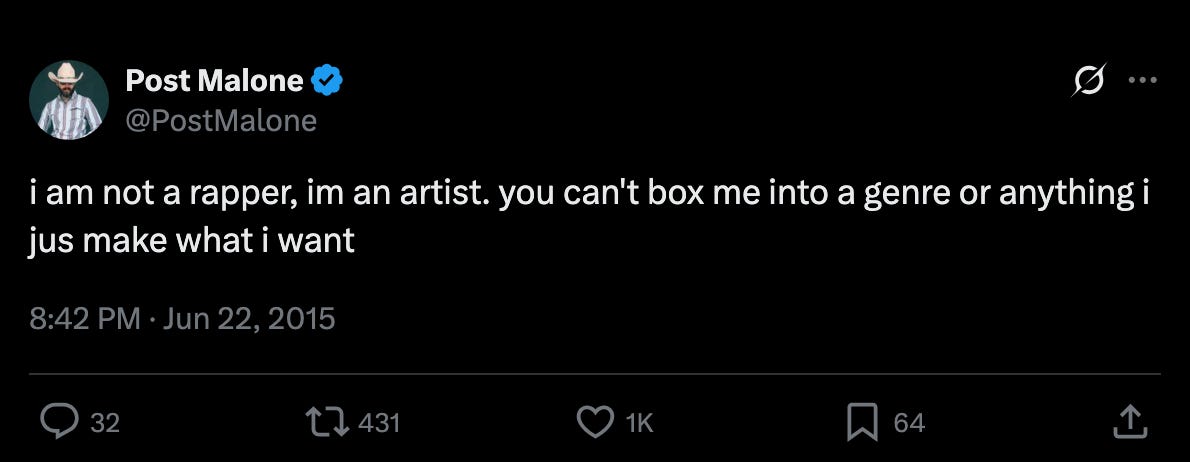

But Post’s pattern predated this controversy. In June 2015, early in his career, he tweeted: “I am not a rapper, I’m an artist. You can’t box me into a genre.” In 2016, he turned down a slot on the prestigious XXL Freshmen list because he was “going in more of a rock/pop/country direction.” And in a January 2018 GQ interview, he lamented: “I definitely feel like there’s a struggle being a white rapper. But I don’t want to be a rapper. I just want to be a person that makes music.”

In that same Rolling Stone interview period, Post claimed he’d been the target of “reverse racism,” which is utter fucking ridiculous, and said of Charlamagne Tha God: “He hates me because I’m white and I’m different.” The pattern is clear when you use hip-hop to gain fame, distance yourself from the “rapper” label once successful, claim victimhood when questioned, then pivot to country music, where you’re welcomed with open arms. In 2024, Post released the country album, F-1 Trillion, and made his Grand Ole Opry debut—the transition was complete.

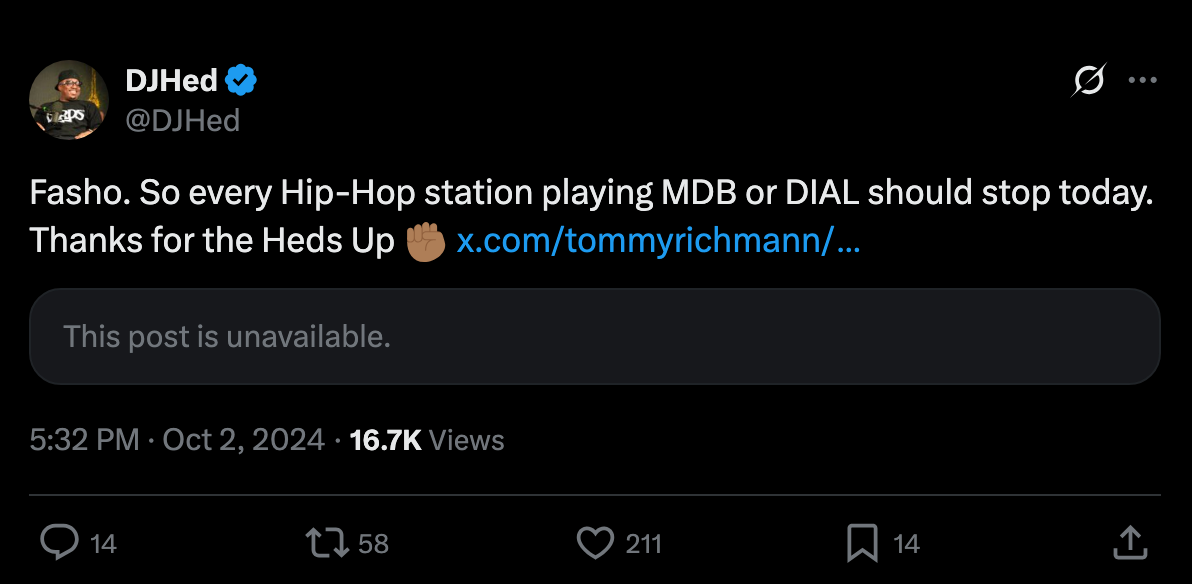

Tommy Richman’s case was more compressed but equally revealing. On October 2, 2024, approximately one week after releasing his debut album Coyote, he tweeted: “I am not a hip hop artist.” The statement came after hip-hop radio, playlists, and culture had propelled his song “Million Dollar Baby” to #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and #1 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart for three weeks. The backlash was instant. DJ Hed, a West Coast radio personality, responded: “Fasho. So every hip-hop station playing MDB [Million Dollar Baby] or DIAL [Devil Is a Lie] should stop today.” He added pointedly: “NO ONE is bigger than the culture.”

Richman quickly backtracked, posting the same day: “I meant to say I’m not SOLEY a hip hop artist” and “I’m saying I don’t wanna be boxed in. I grew up on hip hop. But I’m a singer.” He later described it as one of his “little fucking manic little tweets” and admitted, “I was just seeing discussions about it, and I just wanted to tell people that I was a versatile artist.” Fucking cop-out. The controversy intensified when, two weeks later, news broke that his team had submitted “Million Dollar Baby” for Best Rap Song and Best Melodic Rap Performance at the 2025 Grammy Awards. What a hypocritical crock of shit. The optics were devastating: reject the hip-hop label publicly, then attempt to benefit from hip-hop categories at the industry’s most prestigious awards.

Joe Budden (I hate to quote him) captured the frustration: “You in that group of people that can receive your success and never have to talk to Black people. But the first time you speak... You saying it when hip-hop has broken you and accepted you, it gives us remnants of all of the white acts who their barrier of entry is hip-hop and then they abandoned it.” Elliott Wilson was even more scathing on The Bigger Picture, noting that Richman declined his interview request but sat down with Apple Music’s Zane Lowe: “You’re number one on the hip-hop and R&B charts, but you don’t want to claim hip-hop. And now he submitted his records for the Grammy hip-hop categories.” When the Grammy nominations were announced in November 2024, Richman received zero nominations—a notable “snub” that we all saw as justice served.

The insistence on being an “artist” rather than a “rapper” functions as racial coding. “Rapper” has become synonymous with Blackness, while “artist” suggests a transcendent, race-neutral (read: white) universality. The distinction implies that rappers are limited, one-dimensional, trapped in their genre, while artists are versatile, creative, free to explore. But the box isn’t really the genre—it’s the racial associations that come with it. Being a “rapper” means being associated with Black culture, Black communities, and the perceived limitations and stigmas attached to Blackness in American society. Being an “artist” means claiming access to the full range of cultural production, including white-dominated genres like country and rock.

Scholars have documented how this works systematically. A 2022 study by Van Venrooij and Schmutz, published in Sociological Inquiry, found that Black musicians are less likely than white musicians to be described as category spanners—meaning Black artists’ versatility is systematically underrecognized. Meanwhile, Schaap and Berkers’ 2022 research showed that genre associations operate at a “non-declarative cognitive level”—rock music’s whiteness is implicit, while rap’s Blackness is explicit and marked.

When Machine Gun Kelly switches to pop-punk, he’s celebrated as versatile. When Lil Nas X makes a country song, he’s removed from the charts. When Post Malone pivots to country, Nashville welcomes him. When Black artists make “white music” like punk or metal, they’re chronically under-promoted and rarely achieve household-name status—think of Fishbone, Death, or SOUL GLO, all virtuosic musicians who’ve labored in relative obscurity for decades despite their talent. The double standard is built into the language itself. Andre 3000 can act, play instruments, sing, and compose, but people still just want to know when he’ll rap again. White artists “do” rapping; Black artists “are” rappers. One is a choice, a versatile skill among many. The other is an identity, a limitation, a box.

For decades, the music industry used “urban” as a euphemism for Black music (at times, we can be guilty of that). Tyler, the Creator called it “a politically correct way to say the N-word.” The term originated in the 1970s, when Black DJ Frankie Crocker coined the term “urban contemporary” to make Black music more palatable to white advertisers who were uncomfortable with “Black radio.” The industry maintained entire “urban departments” with Black executives working exclusively with Black artists under white executive leadership. Atlantic Records had a “President of Black Music” but no “President of White Music”—that person just ran the company. The structure created a two-tier system in which Black artists received separate (and smaller) budgets, promotion, and opportunities than pop and rock acts.

Following the 2020 George Floyd protests, major labels announced they would drop “urban” terminology. The Recording Academy renamed “Best Urban Contemporary Album” to “Best Progressive R&B Album.” But the underlying segregation persists—labels still maintain separate departments for Black artists under different names, and chart systems continue to segregate Black music. Billboard has maintained combined R&B/Hip-Hop charts while giving rock and pop individual recognition, perpetuating the idea that Black music is “other,” requiring separate categorization. The historical evolution of chart names tells the story: “Harlem Hit Parade” (1942), “Race Records” (1945), “Rhythm and Blues” (1949), “Soul” (1969), “Hot Black Singles” (1982), “R&B” (1990). Each name change was a superficial attempt to mask the underlying segregation.

When white artists operate in Black genres, they receive measurably different treatment. The 2014 Grammys, where Macklemore & Ryan Lewis’s The Heist won Best Rap Album over Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city, became emblematic of this dynamic. Macklemore himself recognized it, texting Kendrick that he was “robbed” (though he undermined the gesture by posting the screenshot on Instagram for public credit).

Macklemore later analyzed his own white privilege in hip-hop on the 2016 Billboard cover interview: “I think regardless of where you come from or how amazing you are, you’re still a white person appropriating a Black art form.” He noted that mainstream audiences connect with him partly because “I look like that guy,” granting commercial advantages, “they might be reluctant to, in terms of a person of color.”

Eminem acknowledged the same dynamic in “White America”: “Let’s do the math: if I was Black, I would’ve sold half.” Cultural critic Shawn Setaro noted that white artists’ “distancing from ‘rapper’ to the more nebulous ‘musician’ is the sort of thing only white artists attempt—or can pull off. André 3000 can act, play instruments, sing, compose, or write cartoons until he’s blue in the face, and all anyone wants to know is when he’ll rap again.”

Perhaps the most telling evidence comes from comparing who successfully crosses genre boundaries. Fluidity across genres without commercial suicide is possible, but far less accessible to Black artists. Queen ran the gamut from waltzes and skiffle to metal and psychedelia with lasting commercial success. Compare that to Fishbone, who virtuosically fused metal with funk, ska, and soul for decades, yet never became a household name. Death—three Black brothers who played punk before the Sex Pistols—labored in obscurity for decades despite being pioneers.

The National Center for Institutional Diversity research concludes: “When Black artists make ‘white music’ such as punk, metal, and country, they typically don’t get the same level of record-company support and rarely achieve the same popularity as race-genre-aligned artists.” The industry structure creates a self-fulfilling prophecy: Black artists in “white” genres don’t get promotional budgets, so they don’t achieve commercial success, which “proves” there’s no audience for them, which justifies continued underinvestment.

Meanwhile, Post Malone transitions seamlessly from hip-hop to country, welcomed by Nashville’s establishment. BigXThaPlug collaborates with Luke Combs, Bailey Zimmerman, and Jelly Roll on his country album, debuting at #1 on country charts. Machine Gun Kelly pivots to pop-punk and finds immediate success. The pattern reveals that whiteness functions as a passport to cross genre boundaries, while Blackness serves as a border wall. When Tyler, the Creator pushed genre boundaries with IGOR, the Grammys still categorized it as rap, prompting his critique that “guys that look like me” are always put in the “Rap or Urban category” regardless of the actual sound. Genre labels constrain Black artists’ mobility while white artists move freely—because the labels aren’t really about music. They’re about race.

When artists declare “I’m not a hip-hop artist,” they’re not making neutral statements about musical style. They’re participating in a system that devalues Black cultural production while exploiting it for profit. They’re reinforcing the hierarchy that positions hip-hop as artistically inferior, commercially limiting, and culturally stigmatized—a hierarchy rooted in anti-Black racism. The language of “artist” versus “rapper” does real harm. It tells young Black artists that excelling in hip-hop isn’t enough, that true artistic legitimacy requires transcending the genre. It tells the industry that hip-hop albums can win Pulitzer Prizes but not Grammys, that they can dominate streaming numbers but get minimal radio play, that they can generate massive profits but their creators deserve minimal executive representation.

The pattern is exhausting: white artists use hip-hop as a launching pad, benefit from Black cultural infrastructure (radio stations, playlists, festivals, collaborations), achieve mainstream success, then distance themselves from the culture and pivot to “respectable” white genres where they’re welcomed. Meanwhile, Black artists who pioneered those white genres—punk, country, rock—remain marginalized, their contributions erased from official histories. The solution isn’t to police who can make what music. Music should be fluid, collaborative, and cross-cultural. But we must recognize that genre fluidity is not equally accessible to everyone. White artists cross boundaries with career upside; Black artists face career risks. That asymmetry reflects and reinforces racial hierarchies that harm Black artists materially—in a major award show nominations, radio play, promotional budgets, executive representation, and cultural legitimacy.

When artists declare they’re “not hip-hop,” we should ask: Why does hip-hop feel like a limitation? Why is “artist” positioned as transcendent while “rapper” suggests constraint? What does it mean that this distancing language predominantly comes from white or lighter-skinned artists who’ve benefited from Black culture? And what does it say about our industry that the most commercially dominant genre faces systematic exclusion from the highest honors?

The music industry needs structural change: diverse leadership at executive levels, elimination of segregated chart systems, equal promotional budgets regardless of genre, and recognition that artistic legitimacy isn’t determined by proximity to whiteness. Until then, every “I’m not a rapper, I’m an artist” statement serves as evidence of a system that profits from Black creativity while denying Black artists full recognition, respect, and power.

Hip-hop doesn’t need to be defended—it’s already the most influential musical and cultural force of the past half-century. But those who benefit from it owe it something more than coded distancing language. They owe it respect, credit, and a refusal to participate in systems that devalue Blackness while commodifying Black culture. Anything less is exploitation wrapped in the language of artistic freedom.