November 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from ROSALÍA to Armand Hammer, here are notable releases in November that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

This month has unfolded as one of the most richly varied months in recent memory, with artists across hip-hop, R&B, electronic, and soul dropping major statements that feel both deeply personal and broadly resonant. From long-time underground heroes refining their signature styles to newcomers staking out fresh territory, the sheer volume of high-caliber releases speaks to a creative moment that refuses to be contained by genre. Producers are leaning into live instrumentation and fractured beat-making, while songwriters probe questions of faith, mental health, legacy, and romance with unflinching honesty. Whether it’s the return of veteran voices or the relentless drive of those building new imprints, November has become a showcase for artistic autonomy and nuanced storytelling.

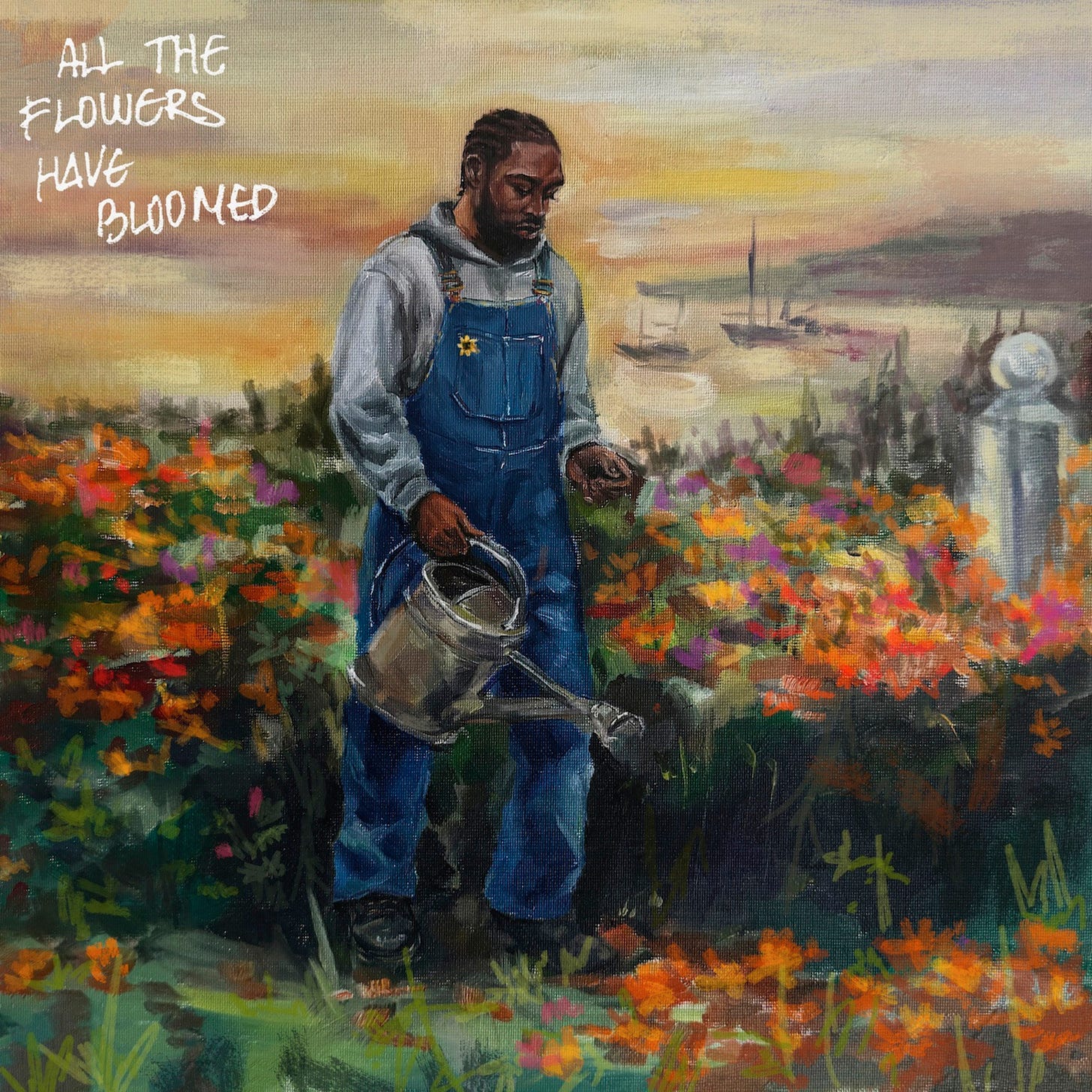

Kofi Stone, All the Flowers Have Bloomed

With this album, Kofi Stone’s style doesn’t shift drastically, but it’s refined. He grew up in Birmingham’s Selly Oak after a family move from Walthamstow, and from that mix of working-class roots and London-edge he forged his voice. A poet grandfather, a father steeped in blues and hip-hop, late nights at studios—these built the tools he uses on All the Flowers Have Bloomed. On “Thorns,” he lays out sleepless drinking, therapy sessions, and parenting in the midst of mental health struggles. There’s no neat redemption or uplift; the verse ends in a question: Is God teaching him a lesson? “Seeds” recounts the move to Brum-town, labels trying to dumb down his ambitions, plus a neighbor housing his family after a fire. The closer, title-track “All the Flowers Have Bloomed,” finds Stone almost celebratory. He opens with a toast (“Everybody in the house, how you doing tonight?”) and pulls together the thesis: the hard years, the planting, the waiting. “All the flowers have bloomed, just like it’s the middle of June.” Yet there’s no ignoring what came before. The sound brings live instrumentation, soulful touches, elements of jazz, funk, and hip-hop layered beneath Stones’s settling voice. The album becomes a map of perseverance, loss, legacy, and renewal. — Ameenah Laquita

Kaila Vandever, Another View

Grammy-winning Brooklyn trombonist Kaila Vandever, whose distinctive approach centers on sonorous tone and lyrical improvisational voice, drew inspiration from Carmen Maria Machado’s inventive memoir In the Dream House for Another View, crafting a narrative about idealization curdling into dread, the way drafts and shadows of a “dream house” reveal themselves once you move inside. Where her previous album, We Fell In Turn, stretched into ambient exploration, this Northern Spy release assembles a quartet with Mary Halvorson on guitar, Kanoa Mendenhall on bass, and Kayvon Gordon on drums into something taut yet breathing. “Staring at the Cracked Window” opens with resilience in mind, specifically the will to break free from harmful cycles, its character hopeful yet surfacing from darkness, a wistful and searching jazz number that showcases beautiful playing from Vandever and really lets Halvorson cook. Compositionally, Vandever drew on Ambrose Akinmusire, Bill Frisell, Radiohead, and Kara-Lis Coverdale, influenced by cyclical forms and free-flowing melodies, reflecting on what surfaces from repetition and intentional listening. “Cycle in Mourning,” “Withholding,” and “In My Dream House” engage heart and head with equal standing, equal parts emotionally challenging and mellifluously accessible, Halvorson’s elastic guitar lines meeting Vandever’s trombone leads in shifting light, while Mendenhall and Gordon give the music its frame, letting repetition breathe in mutable structure. — Nehemiah

De La Soul, Cabin in the Sky

They were visionary and taboo-breaking on several occasions. Despite the sunny nature of their music, released since 1988, the jazz-rap pioneers De La Soul already addressed the story of a girl sexually abused by her father on their second album. Artificial intelligence became a central theme for the trio in their AOI series, which coincided with the turn of the millennium and, soon after, the horrific events of 9/11, in De La’s hometown of New York. They steadfastly distanced themselves from the gangster rap that was flooding their scene at the time. The world always listened to them, far beyond genre boundaries, for example, when they opened for The Flaming Lips or collaborated with the Gorillaz. Their return with Cabin in the Sky was unexpected. But Trugoy, one of the three MCs, didn’t live to see it. The album’s diverse range of expressive modes includes children’s and monster voices, gurgling scratches on the voice, a radio play with screeching and slamming doors, announcements for a breathing exercise, elegant choral singing, and even an introductory round at the beginning. It is a warm, sunny, and emotional work, as can already be seen in song titles such as “Sunny Storms,” “Cruel Summers Bring Fire Life,” and “Day in the Sun (Gettin’ Wit U).” Besides the breadth of themes and vocal delivery, the sound design is also multifaceted, thanks to Pete Rock, DJ Premier, Nottz, Jake One, and others. With the help of a stacked feature list of the year, including everyday philosophical musings, De La Soul goes a big step further and builds upon the historically significant works of their early years. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Ché Noir & 7xvethegenius, Desired Crowns

When does Ché Noir ever rest? She’s already one of the hardest-working MCs in the game. As her fourth release of the year, this time, teaming up with 7xvethegenius, both hail from the fertile grounds of Buffalo, New York, a city that has spent the last decade establishing a brutalist, yet refined, sound within the landscape of underground rap. While both artists initially sharpened their edges under the banners of established industry figures—Ché Noir signing with 38 Spesh’s TCF Music Group and 7xvethegenius aligning with Conway the Machine’s Drumwork Music Group—Desired Crowns functions as a declaration of complete autonomy. Having subsequently launched their own imprints, this joint venture is explicitly about the pursuit and exercise of power. With producers from Black Metaphor to Conductor Williams, there’s no shortage of filler. The chemistry here is mutually elevating, allowing them to tap into a lyrical sweet spot reminiscent of the most potent duos in Rap history—the unflinching street narratives of a Raekwon and Ghostface or the sharp, luxurious cynicism of Clipse. These ladies did their big one. — Harry Brown

FKA twigs, Eusexua Afterglow

Riding off the universal acclaim of Eusexua, FKA twigs decides to double back and hit us with another release in almost ten months’ span. But where the former documented rave transcendence in real time, the latest, released as a standalone sequel initially conceived as a deluxe edition, expands on feelings that come after experiencing eusexua, transmuting them into a soundtrack for hours after the rave and extending that high into the afters. The beats now are fractured and derelict, and playful—most importantly—the culmination of skills across her catalog: dancefloor adoration evident across Eusexua, playful hooks of Caprisongs, vulnerability of Magdalene, sensuality of LP1. twigs proves the afterglow isn’t denouement but continuation, hedonism’s aftermath as generative as its arrival. — Charlotte Rochel

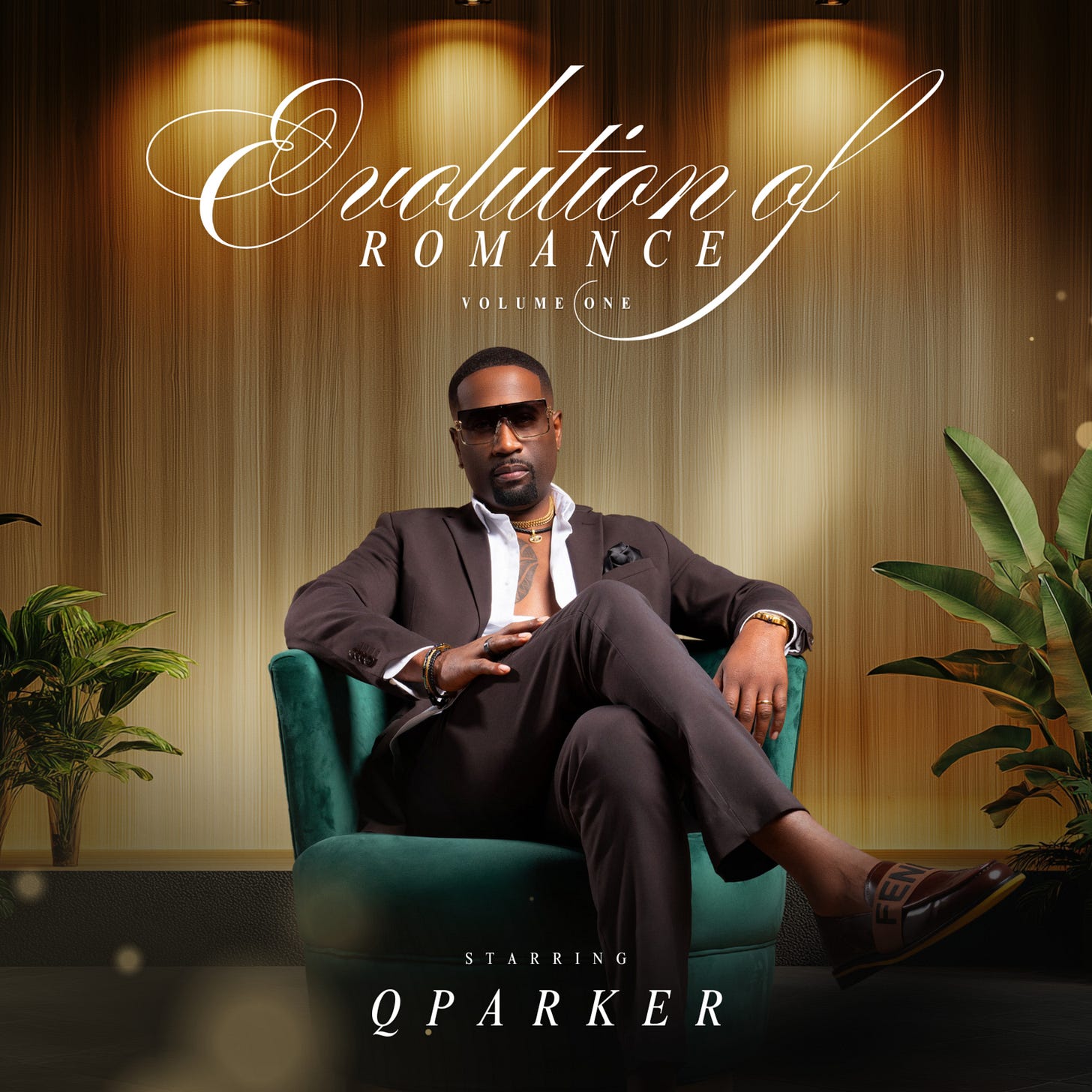

Q Parker, Evolution of Romance, Volume One

R&B’s greatest practitioners understand that romance is documented in how Black men navigate vulnerability in a culture that demands their stoicism. As a founding member of 112, Quinnes “Q” Parker is the mastermind and, with the group’s harmonies, became a radio staple through classics like “Only You,” “Cupid,” “It’s Over Now,” and the Grammy-nominated “Peaches & Cream.” But where 112’s group harmonies created collective romantic expression, Parker’s solo work demands something more personal. His 2012 debut, The MANual, established his solo identity as a vocalist embracing transparency and growth, and thirteen years later, he returns with a mission to reclaim territory he believes contemporary R&B has abandoned. The first volume of Evolution of Romance returns to true romance, courtship, and emotional intimacy. Parker dubbing himself the “Romance Dealer” to fill what he identifies as a crucial void. “BEG,” produced by Blac Elvis, its acronym standing for Bringing Endless Gratitude rather than desperation. “Keep on Lovin’” featuring Rico Love and Dondria flips The Deele’s “Two Occasions,” a nostalgic gesture that reveals Parker’s understanding that romance requires historical memory—you can’t innovate intimacy without acknowledging its lineage. “fff.” embraces being a provider while requesting only three things in return: feed me, be intimate with me, be a fan of me, frank language delivered with grown-man directness rather than youthful bravado. — Imani Raven

Shungu, Faith in the Unknown

Shungu has long built his own signature within beat culture and underground hip-hop—from lo-fi tape experiments to global collaborative projects. On Faith in the Unknown, he pulls a wide net of heavy voices (Pink Siifu, Liv.e, Fly Anakin among them) and a mindset centered on “trust, patience, and creative risk.” Take “Thin Line” with Chester Watson: subtle organ keys, hi-hats that resist typical bounce, Watson delivering rhymes in a come-on-out-of-bed voice. Or “Did You Hear the News” with Ruqqiyah, where deep bass and lofting lounge samples support vocal lines that reach without forcing. What holds the project together is Shungu’s refusal to overstate anything. He isn’t shaping this into a concept piece or trying to build a producer-as-auteur narrative. He’s anchoring each track with choices he’s comfortable standing behind. It feels more like Shungu doubling down on the parts of his method that don’t need fanfare. — Harry Brown

Grimm Lynn, Fire&Smoke

No one does it better than Grimm Lynn. Residing in Atlanta, Georgia—a city whose red clay seems to hold the heat of the sun long after it sets, much like the lingering soul of the Dungeon Family—he previously delivered the solar-drenched warmth of Southern Grooves and the humid intimacy of Sweet Heat. But Fire&Smoke operates on a different axis, a record that toggles between combustion and suffocation. Coming off of contributing Flwr Chyld’s major-label debut, you get the usual aquatic chords of The Neptunes, and the vocal elasticity of Thundercat here, but on tracks like “Palo Santo,” he orchestrates a cleansing ritual of woodwinds and percussion that feels less like a song and more like a spiritual reset. On “Fire,” he leans into urgent, staccato rhythms that mirror the panic of infatuation. He slows the tempo on “Lilies” to a molasses drag, evoking a wilting romance. — Jill Wannasa

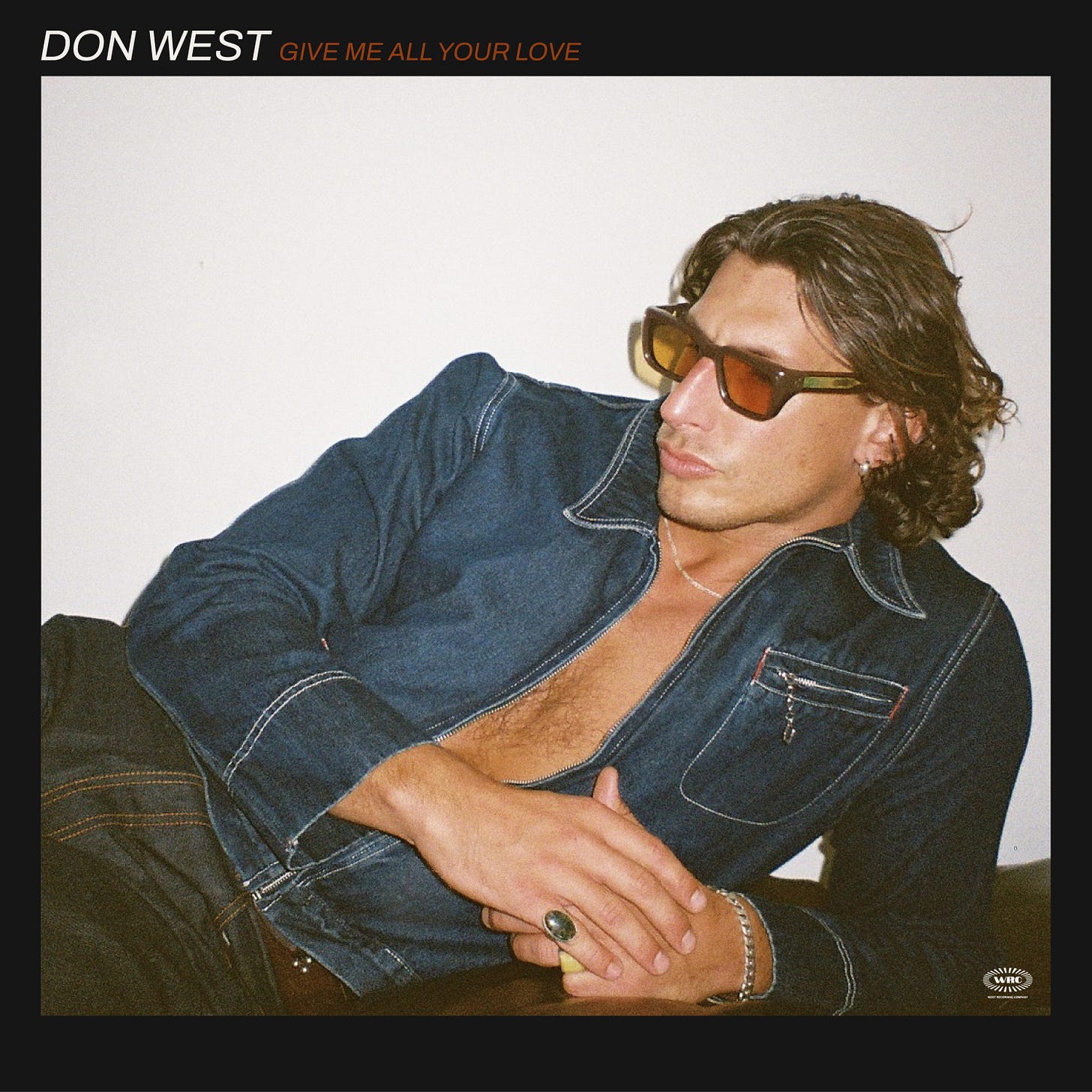

Don West, Give Me All Your Love

Don West found Marvin Gaye’s live albums, where the music barely cuts through women screaming for 40 minutes straight, the kind of frenzy that plants ideas in a young singer’s head. The explosion came fast in his career, as “Small Change” and “Friends” blew up in 2024, pulling him from thousands of monthly listeners to millions. Now there’s Give Me All Your Love, a full-length that locks into the soul renaissance happening globally through artists like Jalen Ngonda and Thee Sacred Souls, but carves out its own humid corner. Nathan Hawes produced and co-wrote the whole thing, recording on the South Coast of New South Wales with multi-track tape and vintage microphones, the twins from Surely Shirley handling choir vocals, a real brass section cutting through analog warmth. You hear Daptone Records in the dripping reverb and funky horns, but West and Hawes push beyond retro worship. On “So High,” jazzy keys dissolve into an extended saxophone solo that could soundtrack a smoky room at 3 AM. “Dreamin” slows to soft-focus drift, nodding to Donnie & Joe Emerson’s 1979 cult classic without replicating it. “Julia” keeps the grooves tight while West questions love with vocals smooth enough to hide the uncertainty underneath. West calls it “coastal soul,” which fits: sun-baked desire meets late-night confession, all captured on tape with the hiss left in. — Imani Raven

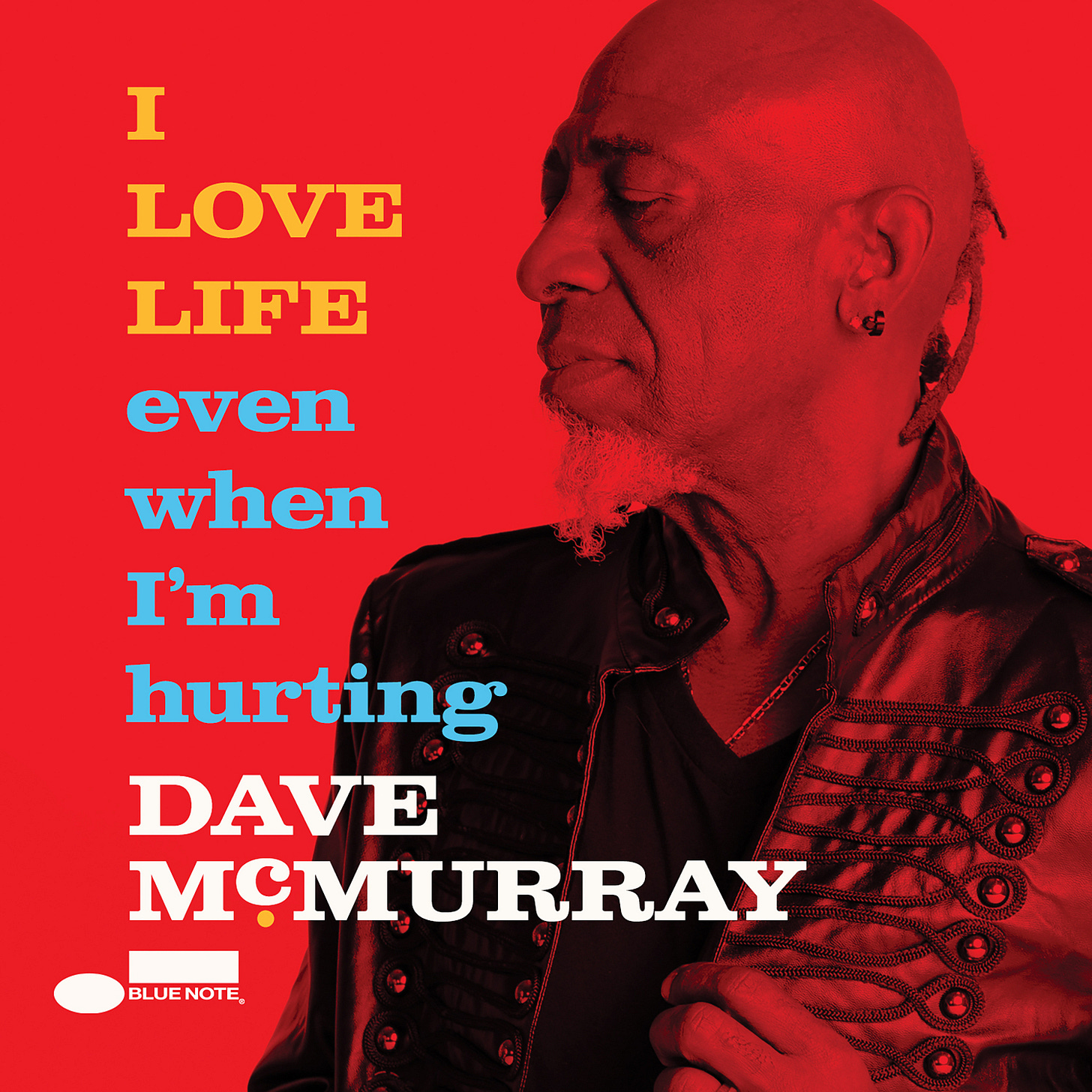

Dave McMurray, I LOVE LIFE even when I’m hurting

Came from a scene where jazz, blues, funk, soul, rock, punk, and electronic music collide, his five-decade journey spanning Was (Not Was), the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Iggy Pop, and nine years in Kid Rock’s Twisted Brown Trucker Band, Dave McMurray studied urban studies and psychology at Wayne State University before music overtook his mental health counseling career. I LOVE LIFE even when I’m hurting arrives as affirmation after deep discussion about a friend worn down by illness who gave up and died alone, McMurray’s unyielding response becoming the album’s narrative: “Man, I love life even when I’m hurting.” “This Life” opens with brawny, iridescent tenor saxophone tone before “The Jungaleers” kicks into ebullient Afrobeat groove concocted by drummer Jeff Canady and percussionist Mahindi Masai, propelled by none other than Don Was on bass—the Blue Note president and longtime collaborator whose relationship with McMurray spans four decades back to Was (Not Was)’s 1981 debut. “7 Wishes 4 G” percolates to a hazy soul-jazz deep house groove worthy of Moodymann or Norma Jean Bell, conceived in 7/4 odd meter while still feeling like house music and sounding like Pharoah Sanders’s “Astral Traveling.” “We Got By,” Al Jarreau’s soul-jazz ballad featuring Detroit’s Kem, brims with themes, while the Yusef Lateef cover “The Plum Blossom” completes a triptych honoring lineage while refusing museum treatment—Detroit’s sonic DNA recombined into positivity. — Nehemiah

Flwr Chyld, InsydeOut

Flwr Chyld has spent years shaping a lane where R&B leans on discipline rather than mood. He came up in Atlanta’s ecosystem of arranger-first musicians, the ones who build their sound brick by brick until something coherent emerges. His early projects showed flashes of that control, but InsydeOut is the first time he drags all the loose ideas into the same room. The album catches him trying to square tenderness, distance, and self-protection without letting the production turn into soft focus. What gives the record its spine is how he handles contrast. He’ll set a warm chord bed, then cut it with clipped percussion or a bass tone that refuses to sink into the background. It’s a way of admitting that the relationships he’s writing about sit on uneven ground. Songs move the same way conversations do when someone is half-trying and half-pulling back. “EmptyBaggage” shows the template clearly—Kent Jamz walks through the messiness of wanting someone while knowing he keeps breaking his own patterns, and Flwr Chyld keeps the beat tight so every line lands without cushioning. — Esther Blake

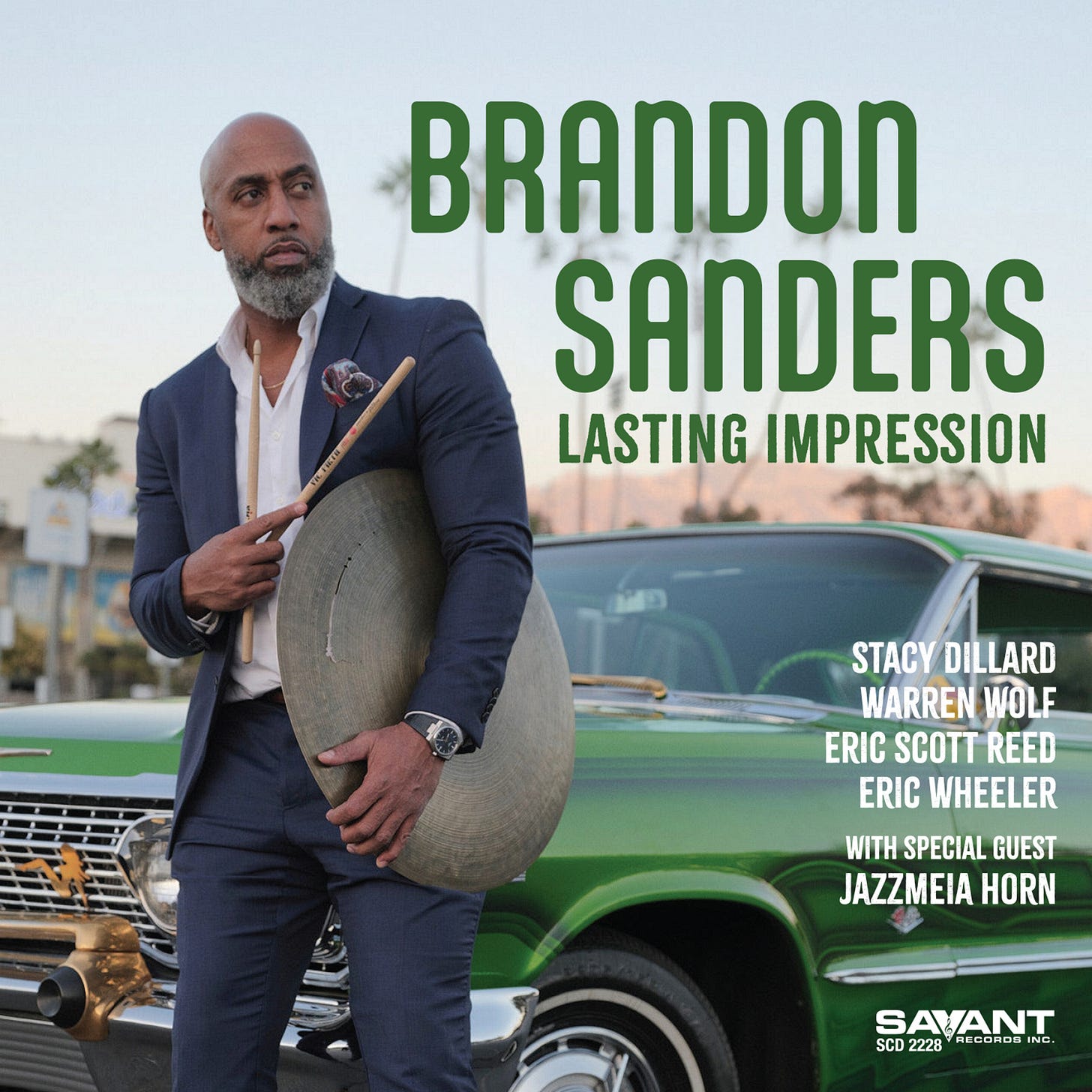

Brandon Sanders, Lasting Impression

Brandon Sanders was 25 years old before he ever picked up drumsticks, releasing his debut Compton’s Finest in 2023 at age 52, but his grandmother Ernestine Parker ran the Casablanca, a Kansas City club where young Brandon spent summers from the mid-1970s through late ‘80s surrounded by Jimmy Smith, Grant Green, and Lou Donaldson—not classroom instruction but communion, baptism in sound. Between those formative summers and his eventual arrival as a bandleader, Compton DJ, and social worker, decades as a college basketball player, and experiences that now enrich and pour forth from his music. Lasting Impression, his third Savant Records release, features vibraphonist Warren Wolf, pianist Eric Scott Reed, saxophonist Stacy Dillard, bassist Eric Wheeler, and Grammy-nominated vocalist Jazzmeia Horn, the constellation designed to linger in memory. Bobby Hutcherson’s “8/4 Beat” opens as a showcase for Wolf, while Reed’s originals “Shadoboxing” and “No BS for B.S.” balance Sanders’ own buoyant title track and poignant “Tales of Mississippi.” Dillard’s take on Mal Waldron’s “Soul Eyes” dives deep into longing and beauty. Horn’s singular style combines the timeless with the futuristic on the Gershwins’ “Our Love Is Here to Stay” and Stevie Wonder’s “Until You Come Back to Me.” — Imani Raven

Johnny Burgos & Jeremy Page, A Long Short Story

These two gifted individuals never fail to make a great pairing. Johnny Burgos spent years navigating brand endorsements and touring with his band, Bridge City Hustle, before connecting with veteran soul producer Jeremy Page, whose credits include CZARFACE, Kendra Morris, and MF DOOM. Their 2024 collaboration (All I Ever Wonder) established their chemistry through retro-soul techniques, but A Long Short Story, their second full-length, arrives as something unexpected—not simply a homage but a transmutation, where Chicano soul and Motown aesthetics collide with contemporary club energy and prog-rap experimentation. “Under Your Window” captures love and urban heartbreak, tempo changing as horns blare in, Burgos hitting notes with sniper-like precision. The title track fills with strings while “Sidelines” bounces with bright flamboyance, striking swashes of purple surrounding them—the specter of Prince hovering without explicit mimicry. Page’s production adapts to Burgos’s range, his influences surfacing not as quotation but as DNA recombined into something that honors lineage while refusing museum treatment. — Brandon O’Sullivan

ROSALÍA, Lux

The sole single, “Berghain,” preceded Lux by a week and immediately sparked a wave of enthusiasm on social media: ROSALÍA is (finally) back with her fourth album. This audiovisual track, accompanied by a cinematic music video, immerses us in a new world of the singer: an homage to the famous Berlin techno club—on which she sings languages in German, English, and Spanish alongside the London Symphony Orchestra —heralds the album’s orchestral and spiritual direction and reveals ROSALÍA’s deep connection to her musical past, which is more reminiscent of an oratorio than pop à la Motomami. Furthermore, this opening to her new album serves as a reminder that her academic training began at the Catalan Conservatory. Now she takes a step back to her musical roots, which still lie dormant deep within her creative expression. With each album she releases, it opens the doors to a new facet of her career—and takes at least several years to develop each of her album concepts down to the last detail. Lux is structured into four movements in the style of a modern oratorio—a structure that lends a sense of order to the album’s spiritual and emotional journey, revolving around the single as a central piece that encapsulates the transition from contemplation to catharsis. It is ROSALÍA’s greatest accomplishment and perhaps most radical personal work to date: an intersection of pop oratorio, spiritual diary, and sonic laboratory. — Charlotte Rochel

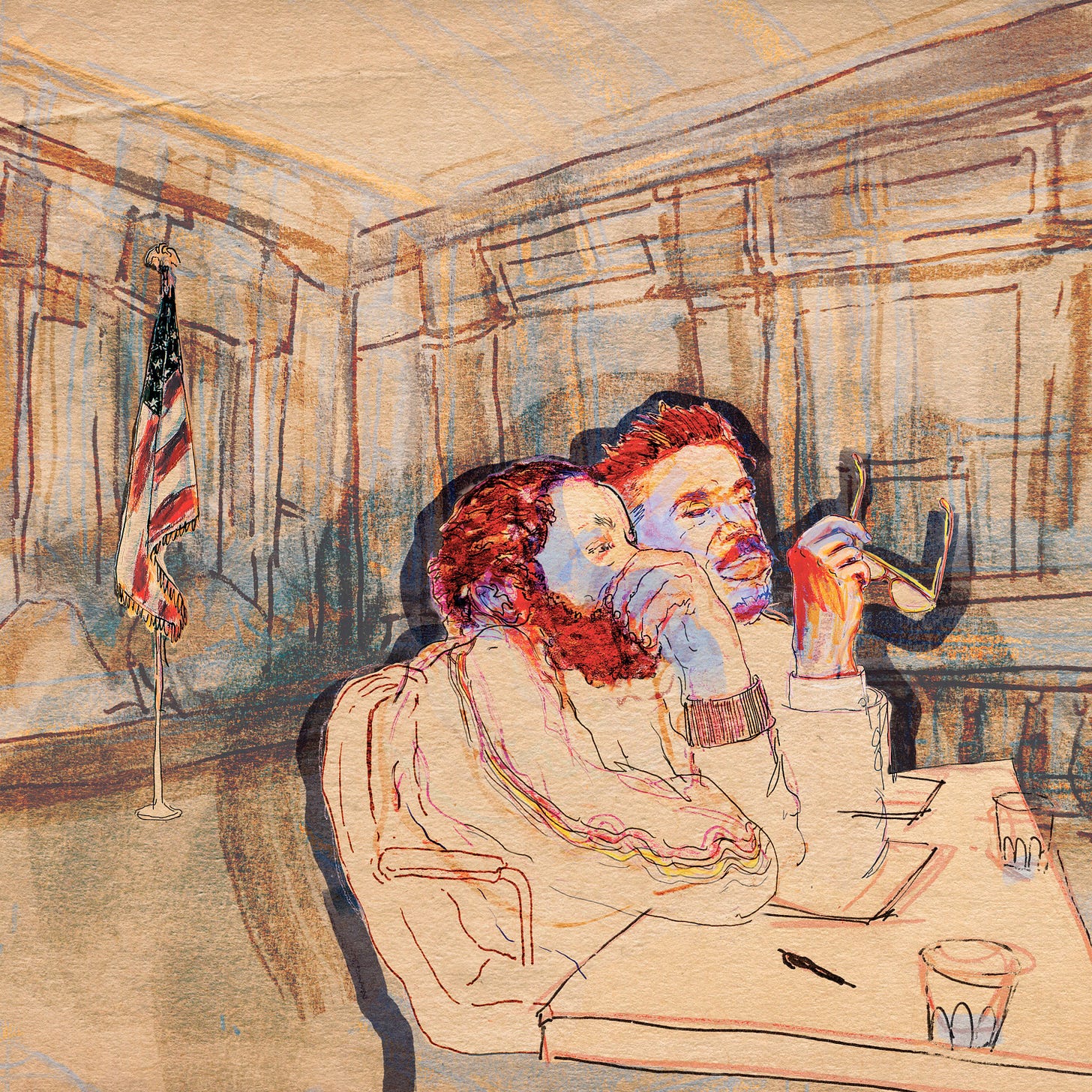

Armand Hammer & The Alchemist, Mercy

In a rap landscape often dominated by predictable narratives and glossy production, Armand Hammer and The Alchemist choose the opposite path. That of depth, with their second collaborative album, Mercy, which is not an album to be listened to distractedly, but a dense and layered work. When reality can no longer be ignored, the only choice is to face it. Alan the Chemist, who has crafted countless underground rap classics, delivers a colder and more precise sonic performance here than ever before. The instrumentals leave behind the light, jazzy samples, immersing themselves in sustained piano loops, nervous percussion, and sounds that march forward like funeral dirges. A perfect backdrop for billy woods and ELUCID’s vocals, which recite tales of environmental violence, loneliness, and systems that push for surrender. Global conflicts, artificial intelligence, and swarms of news: all of this runs through woods and ELUCID’s verses like a common thread linking personal stories to geopolitical issues. Mercy is a gaze, not an escape. Not an easy redemption, but a work that fills the space left between the cracks of the world. — Koda Lin

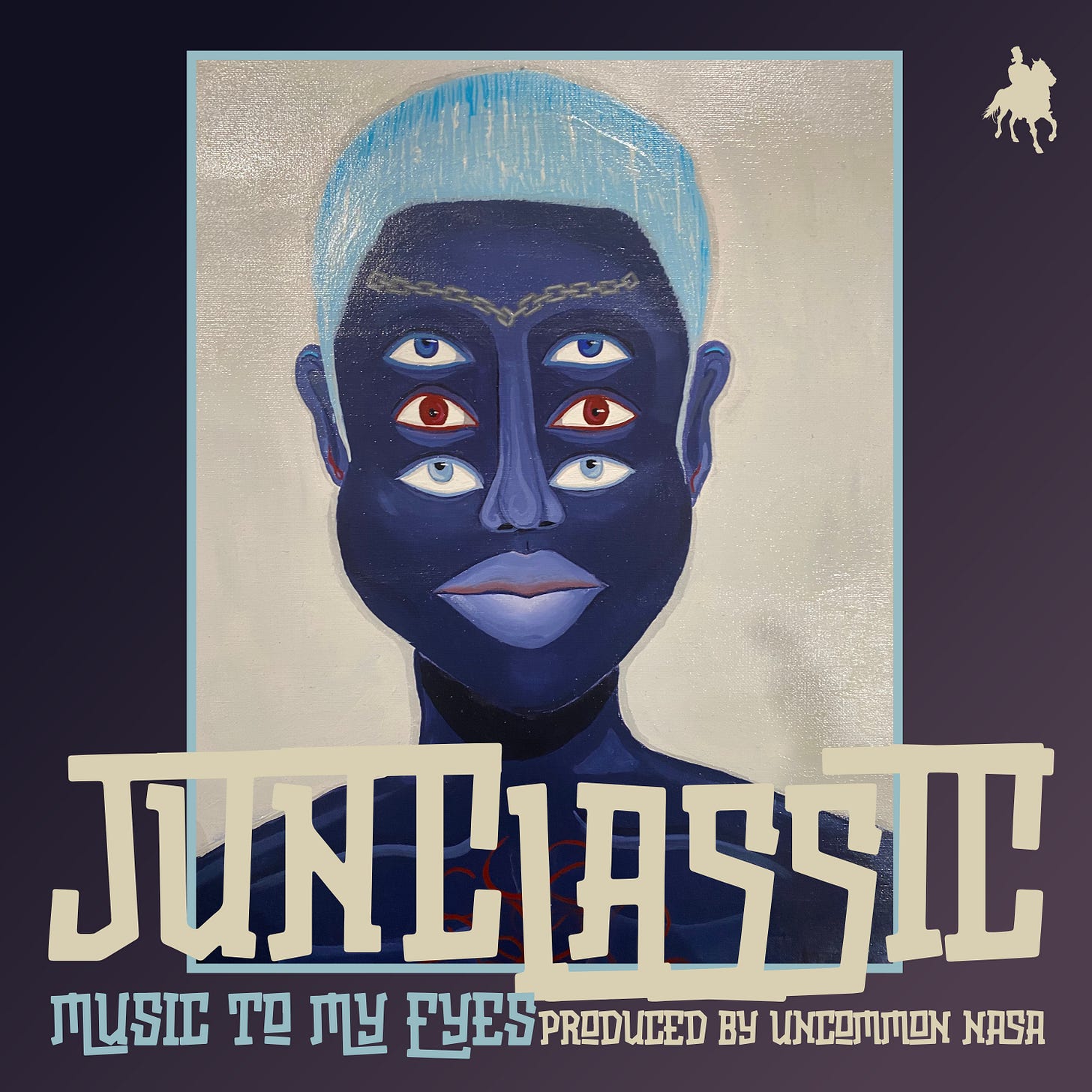

junclassic & Uncommon Nasa, Music to My Eyes

junclassic comes from a place where underground rap meant gritty loops, personal rhyme books, and loyalty to the booth rather than the spotlight. His death before the release of Music to My Eyes gives the record a shifted weight—less a debut and more a closing chapter for what he built. The fact that Uncommon Nasa handles full production gives the record unity while anchoring it in a clear, unified voice rather than a scatter of features. From “1NCE B4” to “Snake Charming,” Nasa steers junclassic through bare-knuckled drums, Rhodes lines, and samples that refuse to sit still. “Glitches” lands with the energy of a group moving as one, the beat loop and the mic loop in sync, not in competition. On “F.E.B.,” the turntables show up as part of the architecture, not decoration, and junclassic rides them without letting them override his presence. He moves through gratitude, loss, and the hunger to stand up in a scene built for collapse. He dedicates the record “to every emcee who had a dream, especially to those who had to let that dream go.” The real note of the album is survival, not celebration. — Phil

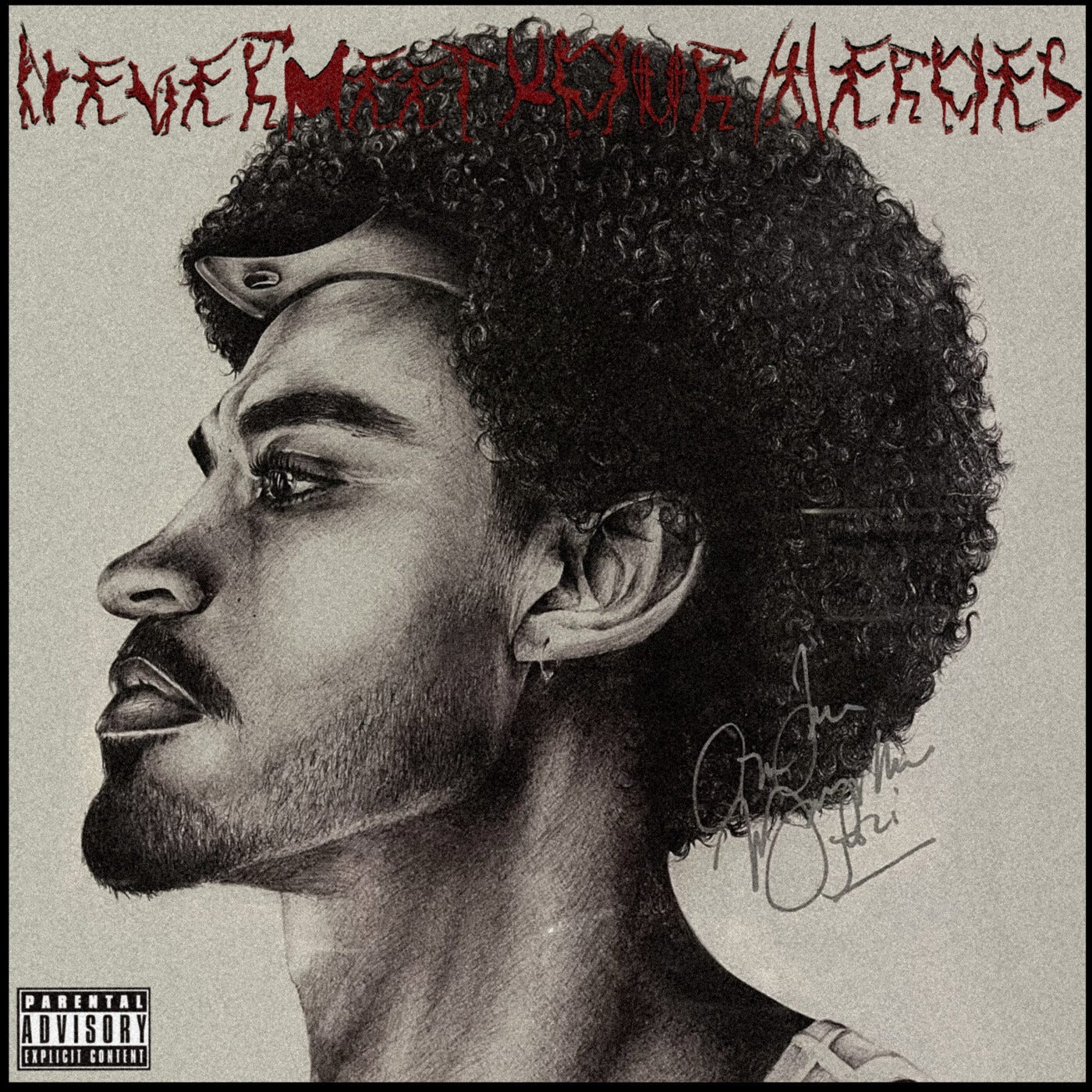

Shane Eagle, Never Meet Your Heroes

Growing up in Johannesburg’s Rabie Ridge, Shane Eagle has always walked the line between township roots and global reach, between faith and street bristle. He comes from a space where ambition meets contradiction. On Never Meet Your Heroes, he steps into a zone of reckoning—of confronting his ideals, his lineage, the pedestal of influence—and plants his mic in that friction rather than avoiding it. The album operates through two clear moves. First, it places Eagle in dialogue with identity, as Son of Yahweh” and “Let There Be Light” signal something spiritual, something that stretches beyond rap’s usual terrain. Then he flips into the grit: “Ride Out,” “Lil D.” and “Wolves” suggest danger, expectation, and life under pressure. There are moments where those mechanics show up plainly. In “Outraged,” he loops a string phrase, letting it wrap around his voice like an echo from a chapel, while the lyrics mention ghosts of ideals and the cost of survival. “Cognac & Cigarettes” trades swagger for confession, the beat tight and sparse, letting his verses hang in a hush rather than filling them with noise. And on “My Daughter’s Hand,” he turns vulnerability outward, giving someone else the vision instead of the mic—this move stakes his place differently, not as a lone hero but as a father, witness, human. — Phil

R.A.P. Ferreira & Kenny Segal, The Night Green Side of It

R.A.P. Ferreira has been turning his own life into coursework for a while now. Small labels to run, a custody battle laid bare on the last record, a shifting list of cities and responsibilities, all funneled into a talky, bookish style that still carries a blues weight. Teaming again with Kenny Segal, he arranges this one as the quiet, late chapter of a trilogy that reaches back to So the Flies Don’t Come and Purple Moonlight Pages. At this every‑few‑years summit, the two of them see how far they can push this shared language without losing the everyday details that keep it grounded. Segal builds the setting from live jazz players and crooked loops—Mekala Session’s restless drums, Skyline Electric’s band takes, Aaron Shaw’s tenor sax, Jason Wool and Diego Gaeta on keys, Jordan Katz’s trumpet, extra bass and tape murk stitched underneath—so the beats feel less like a neat grid and more like a small combo learning to follow a sampler instead of a bandleader. Inside that loose frame, “Spicer and I” lets a scrambled piano line finally settle into a strut while Ferreira flips between bragging and self‑correction. Somewhere else, “By the Head” wraps thin strings around a dry drum pattern as he pokes at the question, “Is the language alive?” “Credentials” drops a memory of his grandfather explaining what fatherhood costs, as “Defense Attorney” stacks images of injured children, demons, and his own exhausted empathy into a plea that sounds aimed at a judge and at himself. — Harry Brown

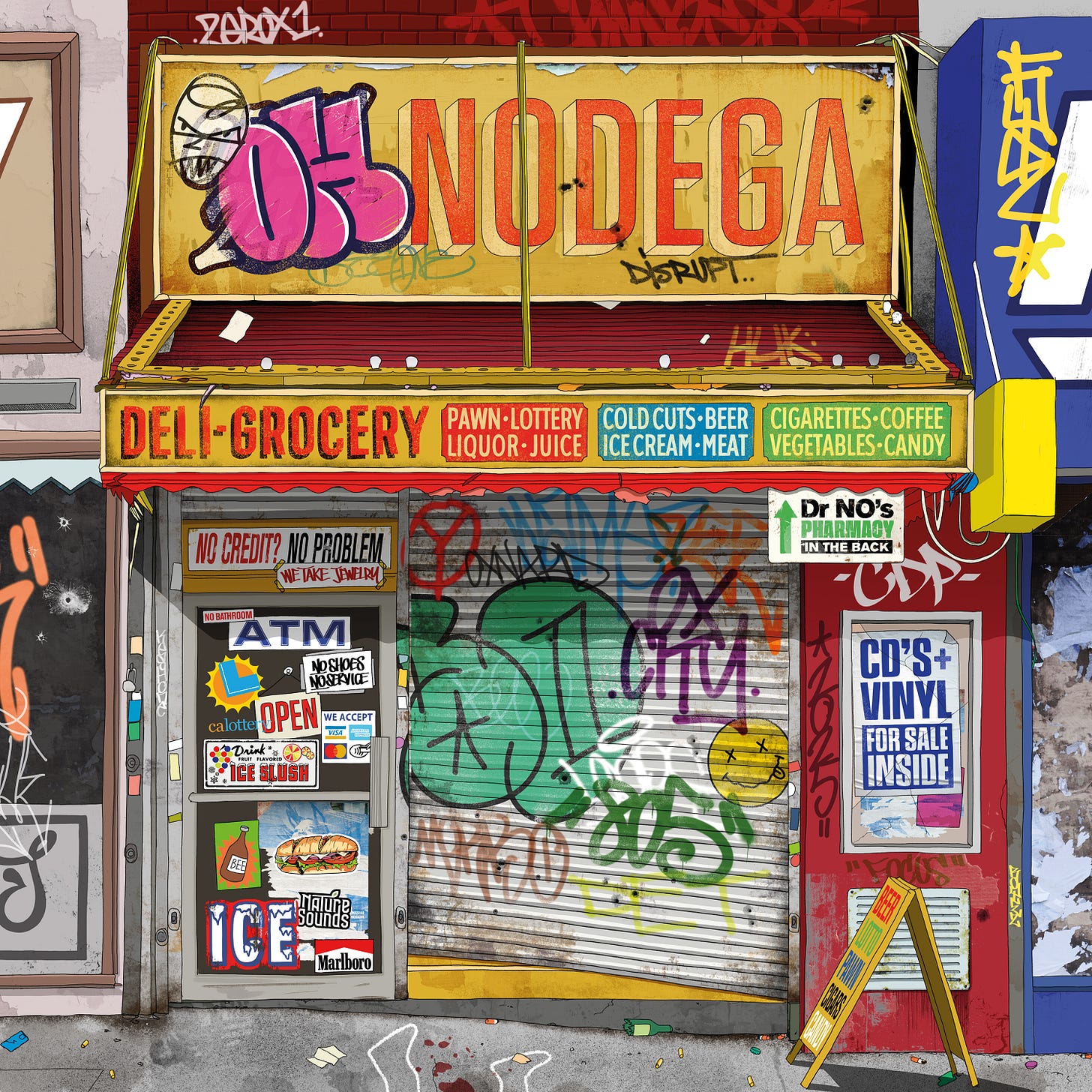

Oh No, Nodega

Where his brother Madlib became hip-hop’s mad scientist, fragmenting soul into abstract collage, Oh No erupted as the visceral counterpoint—his 2004 Stones Throw debut, The Disrupt, announced a producer who could make drums feel like blunt force trauma. But while his sample-based instrumental suites have long explored far-flung sounds, mining Mediterranean psyche-funk on Oxperiment, Roy Ayers’ cosmic jazz catalog, and the dusty corners of Italian library music. Nodega finds him returning to the bodega’s fluorescent-lit urgency, the corner store as both sanctuary and war zone. The album’s concept materializes as a neighborhood bodega where microphone assassins congregate to document street chronicles, but Oh No’s production transcends simple boom-bap nostalgia. On “Gutter Streams,” he reunites with The Alchemist as Gangrene, their chemistry recalling the paranoid funk of early Mobb Deep. “Nodega Run” employs vibraphones to anchor J. Sands’s storytelling, the rhythmic shimmer evoking Detroit’s most introspective moments. “ICU With Bottle Service” samples what sounds like 16-bit video game warnings, transforming digital arcade menace into street-level threat. The album’s genius lies not in reinvention but in Oh No’s understanding that the corner store, like the drum break, like the sampler itself, remains hip-hop’s most democratic space, where veterans like Ghostface Killah, Rah Digga, and Talib Kweli share oxygen with Tha God Fahim and CRIMEAPPLE, all congregating under flickering lights to testify. — Harry Brown

Tawobi, Rosemary’s Baby

Tawobi bills himself as “Rosemary’s only begotten sun,” a deliberate misspelling that transforms Polanski’s 1968 occult nightmare into autobiography. Where that film tracked paranoia and possession through pregnancy, Rosemary’s Baby tracks what gets birthed when you refuse to let systems abort your ambitions. The project features production largely from Oldman, moving through tracks that document the transition from uncertainty to uncompromising purpose. “Amerikkka” arrives as a sonic indictment that triple-K spelling inherited from Ice Cube and dead prez, and “Now That’s What I Call Music” ironically appropriates that compilation series’ title for something considerably less sanitized than pop radio allows. The album closes with a voicemail from Tawobi’s father, “Hey Oldman, where the hell are ya?” addressing him by family name, the same voice that narrated his 2020 album F.A.T.E., teaching the lesson of eating the elephant one bite at a time. But this conversation marked the first time since childhood that his father had doubted or regretted encouraging him, with paternal uncertainty sliding into the end of the song “13,” written when HBC’s core members moved into their first collective house in 2016. Tawobi proves that Philadelphia’s basement isn’t a burial—it’s an incubation chamber for what refuses to stay underground. — Koda Lin

Apollo Brown & Ty Farris, Run Toward the Monster

Longtime veteran producer Apollo Brown arrived just as the city’s post-Dilla landscape demanded producers who could honor boom-bap tradition while documenting contemporary collapse. Enter Ty Farris, who came up from Detroit’s cutthroat battle scene as T-Flame before evolving into one of the underground’s most prolific chroniclers of street life. His No Cosign Just Cocaine series became his calling card—gritty, introspective meditations on survival without industry backing. Run Toward the Monster centers on confronting internal and external fears, in other words, “fear meets concrete,” and across these tracks, Brown’s production provides exactly what the concept demands: grimy, soul-drenched textures laced with surgical clarity. “Follow My Soul” opens with Brown’s thick bass lines and clipped vocal fragments, while “No Celebrations” focuses on the relentless grind required to reach the top and the humility needed to stay there. “Sacred” tightens around chopped soul fragments wrapped around straightforward drum patterns, Farris treating the microphone as both confessional and weapon. “Flawless Victory,” featuring Top Hooter, uses a flute sample to create an eerie, floating hook as the drums keep the track rooted, and “Young Rebels” speaks directly about younger generations navigating the same storms, the same traps, the same cycles. — Harry Brown

Mavis Staples, Sad and Beautiful World

When she was little and too lazy to rehearse for the family gospel group, Mavis Staples received this warning from her father, Roebuck “Pops” Staples: “Your voice is a gift from God. If you don’t use it, he’ll take it back.” As devout as she was, a talented singer, Mavis Staples listened to her father and never stopped singing. For over 70 years, it’s been almost an eternity. Since We’ll Never Turn Back in 2007, Mavis Staples’ discography has been a generous and flawless collection, an impressive celebration of her family history and the best way to capitalize on it. From Ry Cooder to Ben Harper, by way of Jeff Tweedy and M. Ward, everyone is eager to produce Mavis Staples’ albums or offer her songs. She has become a kind of queen mother of American music. And there’s nothing exaggerated about that: you only need to see her on stage in the 2000s (or listen to her live albums) to understand that the singer is an almost miraculous force of nature, more energetic, radiant, dignified, and generous than the average person. At 86, she’s back with the poignant and essential Sad and Beautiful World, whose title (borrowed from a Sparklehorse song covered here) shows that, once again, Mavis Staples has it all figured out. — Kendra Vale

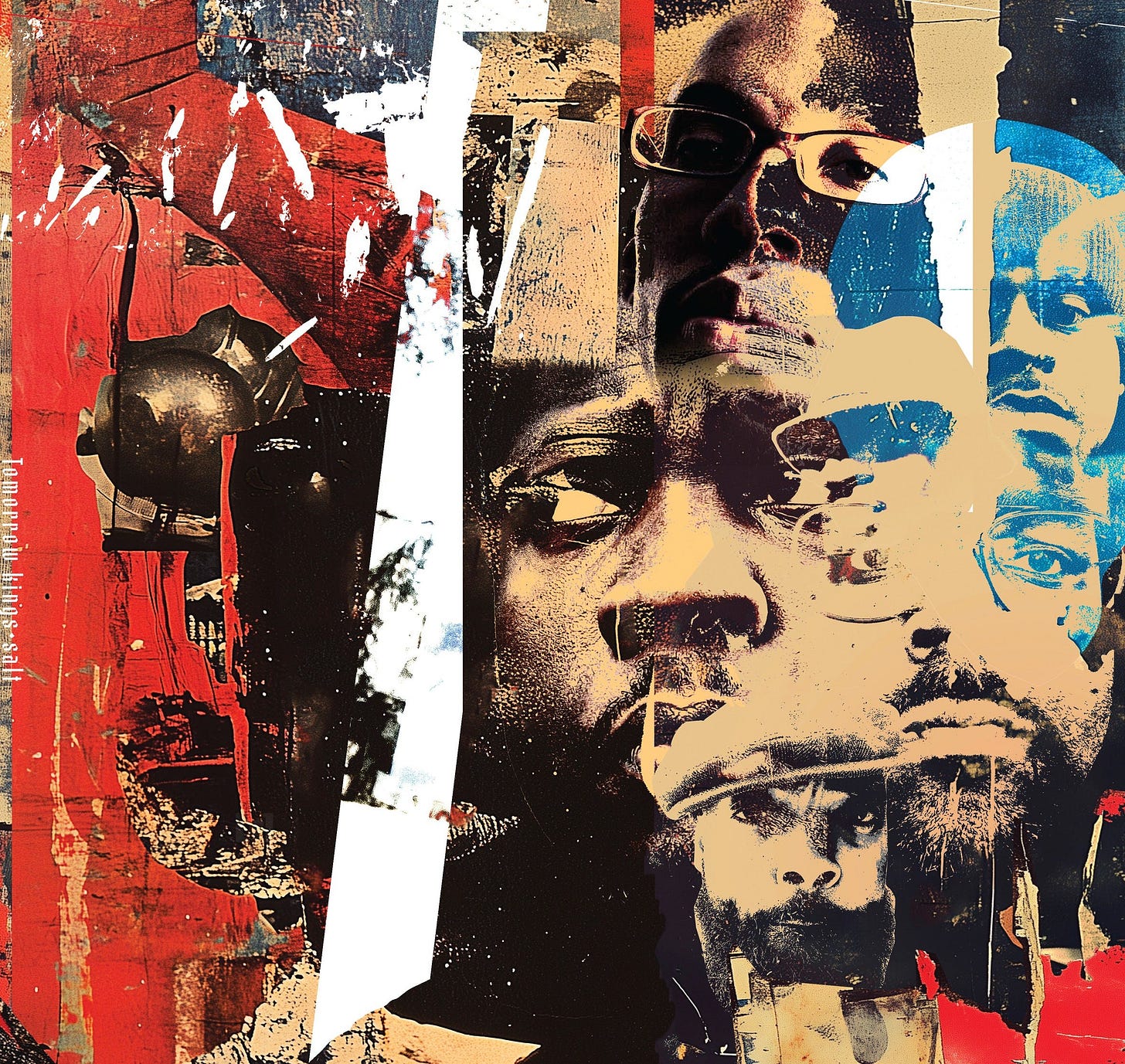

Tomorrow Kings, SALT

With their 2013 debut, Tomorrow Kings made that clear in every bar. It pushed back against racism and systemic neglect while warning any flimsy rapper who thought they could hang. The record landed so hard, they let a dozen years pass before returning. Recorded during the height of COVID-19, SALT picks up that thread with a quieter confidence, pairing street-level anger with dispatches from a world that looks even more unstable than the one they came up in. You find post-industrial soundscapes here, dust-heavy drums here, chopped horns and sirens wailing here, but “Regicide” opens with Collasoul Structure’s four-year-old daughter Ava singing “This world will never end,” an eerie lullaby that sets up everything. On the title track, IL. Subliminal builds a collage where processed cocoa leaf becomes sugar and cocaine, where salt masks the smell of dead flesh, where diabetes and hypertension kill as many people as the Klan and Reaganomics combined. Salt as preservative and poison, a necessary mineral, and a metaphor for the injuries Black bodies absorb. What stands out this time is how focused the group sounds after all that distance. “No Brands” packs all of America’s absurdities into four minutes, abstract and heavy, refusing to choose between marketability and authenticity. Defcee guests on “Airblades,” Curly Castro and the late Jason Gatz appear on “Stains,” D2G shows up for “B-Side Losers,” all of it literary impulse and working documents for surviving capitalism and structural racism, all of it battle rappers acknowledging everything is political without making political rap. — Phil

Ben Reilly, SAVE!

Raised on Nas and Rakim before relocating to Atlanta as a teenager, Ben Reilly named himself after Marvel’s Spider-Man clone, a secondary Peter Parker whose entire existence questions what it means to be authentic when you’re built from someone else’s DNA. Hip-hop’s most compelling concept albums understand that superhero mythology isn’t escapism—it’s camouflage for excavating masculine vulnerability in a culture that punishes Black men for admitting they need rescue. But where Freelance operated at high-wire velocity, SAVE! arrives from pressure rather than energy, the Heroman mythology shifting from costume play toward negotiating what he owes himself versus what everyone demands from him. His debut functions as personal superhero narrative exploring resilience, responsibility, loyalty, and self-discovery, but the architecture is confessional rather than triumphant. “Bulletproof” admits his heart is Kevlar yet concedes “A man of steel is just a man, still.” A standout, “Hero Complex,” builds three verses around conversations with his mother, who questions whether he can’t look for a father in his friends or count on the world to pretend for him. Reilly allows contradictions to coexist, where claiming loyalty is bulletproof one moment, confessing he can’t recall the last time he didn’t share his open home the next. — Rafael Greene

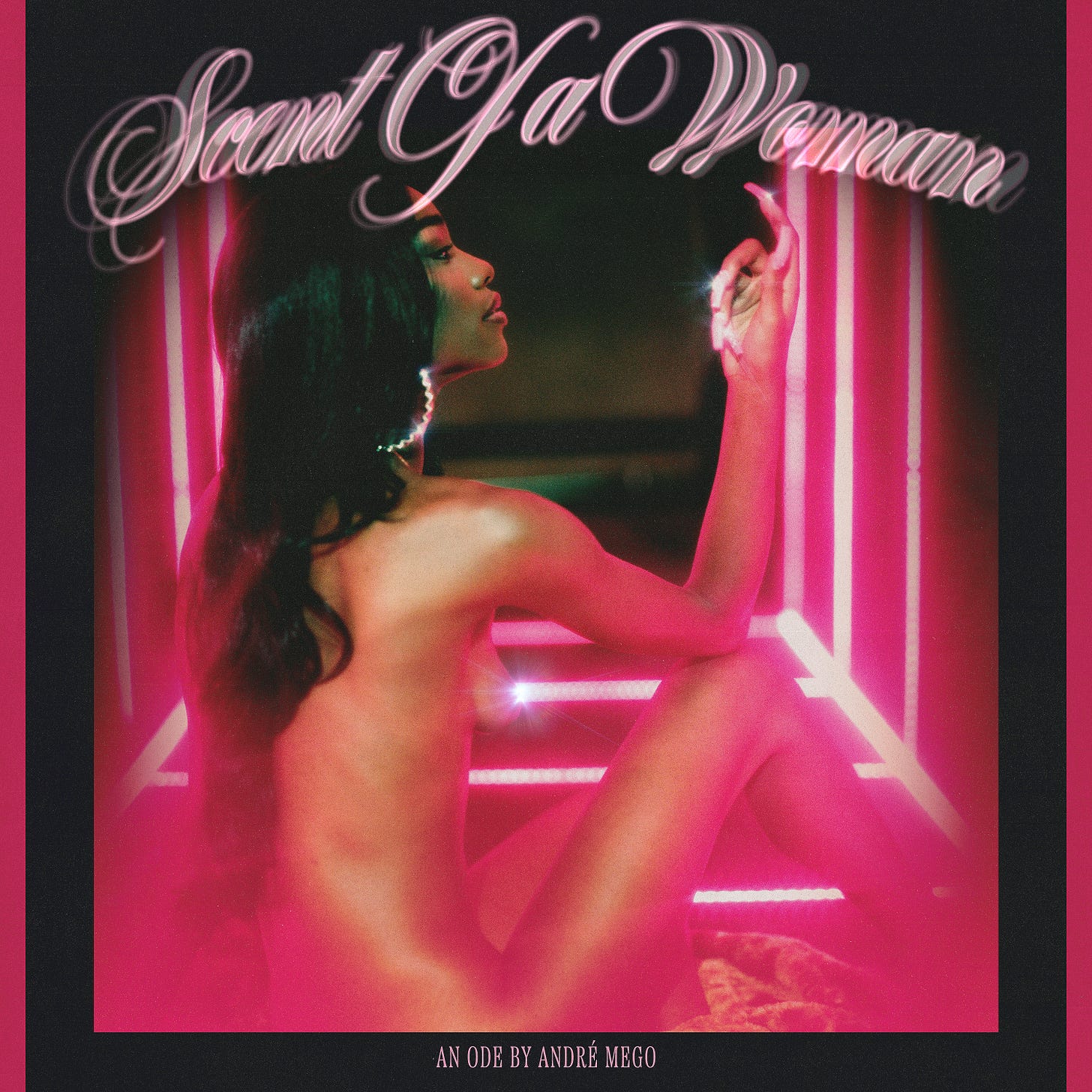

André Mego, Scent of a Woman

Raised in South Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, classically trained on piano, and pushed through pre‑med at Duke before becoming a producer and merch coordinator for 9th Wonder’s Jamla Records, André Mego has long treated hip‑hop as a spiritual syllabus, publishing books like A Wounded Lion and Reverend Duckworth that mine Kendrick Lamar for theology and poetics. Now, as Rapsody’s business partner and co‑founder of the We Each Other creative house, he pours that scholarship into a lush, cinematic ode to womanhood he keeps portraying as “for women to feel seen, not looked at.” If his earlier One Night EP Vol. 1: An Ode to Brotherhood tightened his production into a compact hip‑hop suite with Chris Patrick and Niko Brim, Scent of a Woman widens the frame, pulling in an ensemble that includes Tanerélle, Domani, Tiffany Gouché, Durand Bernarr, Wyann Vaughn, Reuben Vincent and others across songs like “Setbacks,” “Back & Forth,” “Come to My Room,” “Body,” and “Lover.” The record sits at the crossroads of the soul music he grew up on—Nas and especially D’Angelo’s devotional harmonies—Jamla’s jazz‑rap swing, and the tender alt‑rap balladry of Mac Miller, whose song “ROS” is reimagined as “Sunshine or Rain.” This project is a short film about desire, care, and the radical act of adoring women without ever reducing them to scenery. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Domo Genesis & Graymatter, Scram!

If, like us, you’ve been following the scene for many years, you’ve inevitably come into contact with Odd Future, one of the most revolutionary rap groups of the 2010s. Younger people may not know about it, given that it effectively disbanded as a crew about ten years ago, but you’ve undoubtedly come into contact with many of the talents that arose from it: Tyler, the Creator, Frank Ocean, The Internet, Earl Sweatshirt, to name the biggest ones. But alongside these artists who have achieved remarkable solo careers, there are many other talents, unfairly left in the underground, who deserve greater commercial success. One of these is certainly Domo Genesis.

But since 2023, Domo Genesis seems to have found its definitive path, one that allows it to combine quality and productivity like never before. The credit goes to its producer, Graymatter, who always seems to give Domo the foundation he needs. Their partnership has spawned a maxi-single, a project, the EP released this year (World Gone Mad), and now, Scram! Throughout these releases, the technical level is consistently high, with songs that are enjoyable to listen to and powerful yet never banal. With Evidence and 3wayslim as featured artists, Domo has always been more accustomed to more classic rap sounds and, therefore, less eclectic than other members of the group. Rap is a true outlet, a way to talk about himself and lay himself bare. Over the years, Domo has told us about a myriad of personal and family issues, such as the serious disability of a younger brother he’s raising, and this record is no different. — Koda Lin

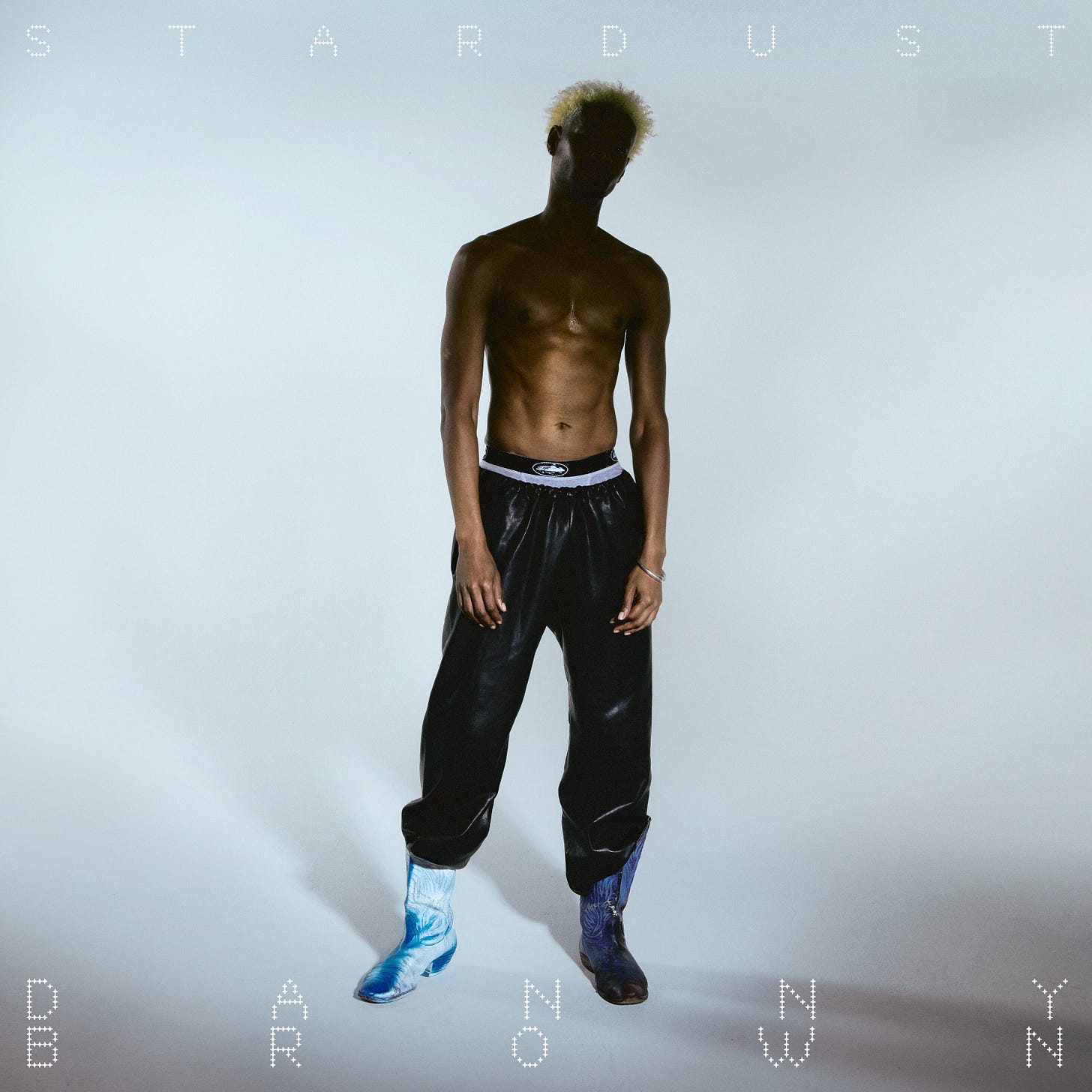

Danny Brown, Stardust

Armed with a singular creativity, Danny Brown brought a new hue to Detroit and the hip-hop scene when his second album, XXX, became a symbol of what the genre could become through word of mouth on the internet. This madcap ride of albums was fueled by a schizophrenic personality, master of a controlled chaos in which addiction played both a blessing and a curse. Precisely for this reason, when Brown decided to get completely clean in 2023, his primary fear was losing that creative magic, undoubtedly seasoned with narcotics. Stardust casts doubt and reveals an artist renewed but fundamentally and essentially still himself. This may be challenging for the casual fan, but for Danny Brown fans, it’s a sigh of relief and a great testament to creativity in its most sober form. The effortless rhymes of “Green Light” support the pop nuances of Frost Children, transporting us to a dimension poised between early 2000s pop rock and a genre capable of inflaming the stages of Blade Runner-era Los Angeles. Dariacore and EDM hues separate the generational gap between Danny and the incredible Jane Remover, whose closing track, “All4U,” reveals the Detroit rapper’s gratitude for all the support he’s received. Danny Brown’s post-sobriety newfound lucidity reaches its climax before the closing credits in the gigantic eight-minute “The End,” in which, accompanied by Ukrainian rapper Ta Ukrainka and Australian rapper Zheani, Danny goes from doomed rapper to uncle-mentor. — Randy

Navy Blue, The Sword & The Soaring

On The Sword & The Soaring, Navy Blue stays committed to the approach of working at the edge of his own interior world, turning small moments into anchors. He handles the music the same way he handles his life—quietly, with the weight of lineage and self-examination sitting in the same space. He builds the record around choices that don’t announce themselves. “Orchards” takes a loop that carries a faint unease and lets the verses walk through it without trying to stretch the moment into something larger. “God’s Kingdom” follows the same logic. He talks about grief and inheritance while keeping the production unobtrusive, so nothing distracts from the responsibility he’s naming. On “24 Gospel,” Earl Sweatshirt enters the track like someone stepping into a conversation already in motion, and Navy keeps the pacing steady so the shift doesn’t distort the song’s shape. What stands out across the album is how settled he sounds in the work itself. He doesn’t chase elevation or reinvention. He keeps the focus on the craft he trusts and the history he carries, and the record holds because he refuses to dress any of it up. — Harry Brown

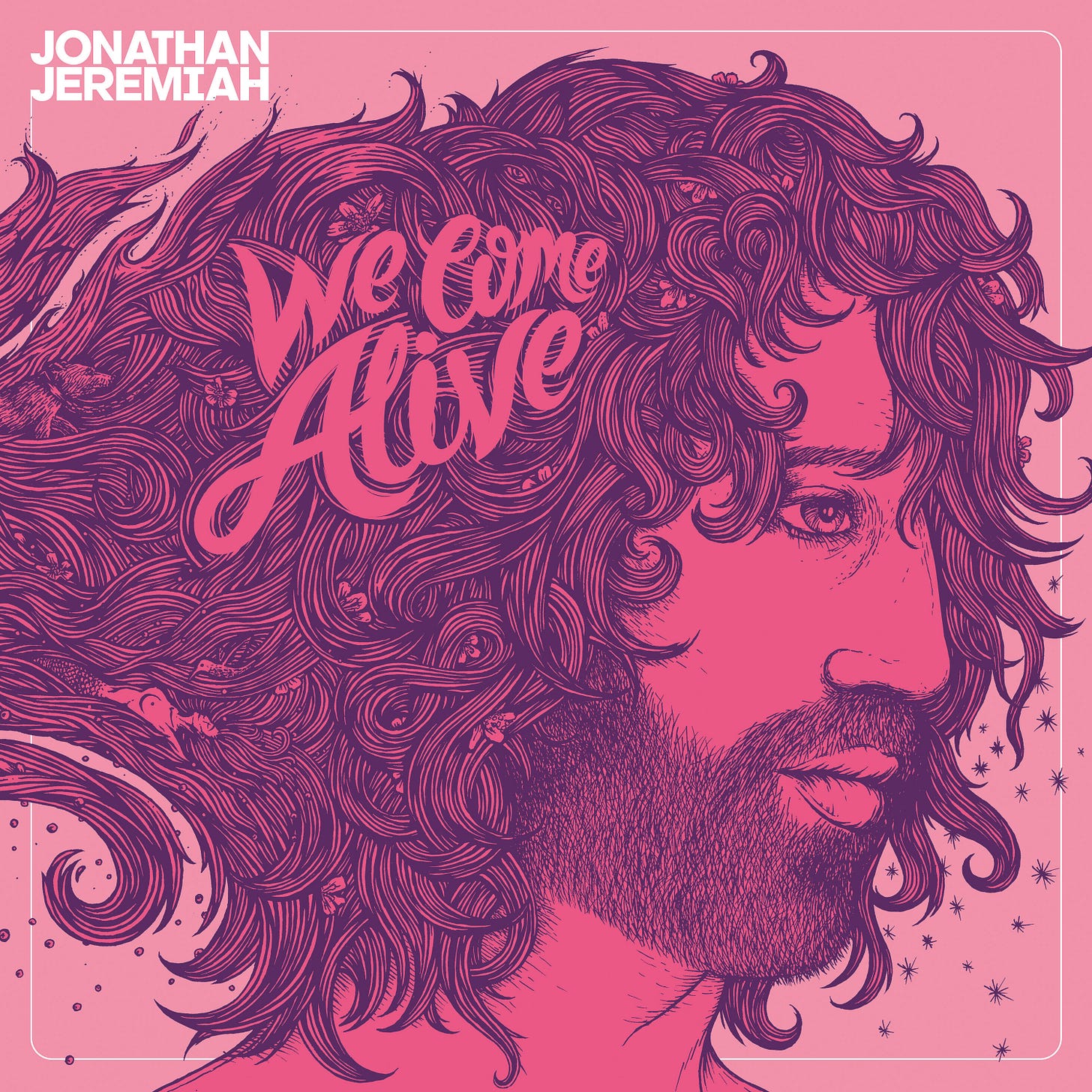

Jonathan Jeremiah, We Come Alive

Jonathan doesn’t retreat into introverted self-analysis beneath the sometimes lush arrangements, but instead marches boldly towards the listeners. He reveals his need to communicate, enchantingly delivering well-chosen, often nature-inspired metaphors. A beautiful woman choir, soulful compositions, and classical elements in the cinematic instrumentation repeatedly push the boundaries of the genre, steering the folk storyteller toward Scott Walker, a crooner, and a chansonnier. The individual pieces all reach a high level, while at the same time providing creative variety under a homogeneous roof. “Counting Down the Days” sounds a bit sweeter and more dramatic, where “Lorraine and the Mermaid” shimmers with a more poetic, sophisticated feel, and the title track has the most exciting mix. “Kolkata Bear” goes faster, is catchier in the ear, quotes the sixties more strikingly; “The Suntrap” scores in dramaturgy, loud-silent dynamics, and psychology; “Lush” delivers first-class Northern Soul. Great, indispensable, warm, nostalgic, and soulful are all these songs—a strong record and another increase compared to the predecessor. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Celeste, Woman of Faces

Where the influences of Amy Winehouse weaponized self-destruction and Adele built cathedrals from heartbreak, Celeste interrogates the performance of identity itself—the masks women wear to survive love and industry expectations. Coming off the extremely underrated Not Your Muse, Woman of Faces was born from the slow unraveling of a romantic relationship and label pressures that left her drowning in depression, a chronicle produced by Grammy winner Jeff Bhasker and Beach Noise (who famously worked with Kendrick Lamar). Nothing is more apparent than “On With the Show,” an anthem and industry critique, whereas “Keep Smiling” exposes how forced smiles become polished trophies. The title track arrives with sweeping string arrangements plucked from Old Hollywood scores, a modern meditation on female identity questioning “Who really knows the woman of faces?” “Could Be Machine” provides the album’s sole industrial detour, using noise to mimic the alienation of online abuse seeping into personal life, and “This Is Who I Am” offers a James Bond-esque declaration, the final unmasking reclaiming identity with quiet authority. — Charlotte Rochel

Zheani's album, with a Danny Brown feature, is fantastic like his is.