October 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from Mobb Deep to Sudan Archives, here are notable releases in October that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

This month of releases felt like music pulling in every direction at once; toward memory, renewal, and risk. In R&B, hip-hop, soul, and experimental pop, artists reached back not to relive history but to rework it. As you go through this list, this speaks in dialogue: between eras, between textures, between the selves these sounds keep inventing, and together they sketch where the culture stands now—restless, porous, alive.

Edo. G & Parental, 500 Miles

Recorded across continents but bound by a shared reverence for hip-hop’s essentials, 500 Miles finds Boston stalwart Edo. G sharpening his voice over Parental’s smoky, sample-heavy beats that crackle like worn vinyl. The album plays as both correspondence and confession—Edo. G raps about endurance, community, and legacy with the clarity of someone who’s walked every block of his story. Parental’s production cuts deep with dusty drums, upright bass loops, and horn fragments that echo mid-‘90s boom bap but breathe with present-day restraint. Across its runtime, 500 Miles becomes a meditation on distance and persistence, a proof of life from artists who refuse to age out or water down. It’s a working-class masterpiece built on tone, craft, and the stubborn will to keep moving, no matter how long the road. — Harry Brown

PARTYOF2, Amerika’s Next Top Party!

Longtime LA partners SWIM and Jadagrace first discovered each other as babies, folding music into grouptherapy. sessions before an identity fall damaged their friendship, forcing them to piece together ashes into this invincible twosome, to the shock of the scene. They signed to Def Jam and their foot stays on the gas. Amerika’s Next Top Party! for their very frailty, their shade-throwing, into constructing every song as a comeback narrative where shade-throwing becomes a collective spotlight that makes the mess of relationships strained by fame shine. “Survivor’s Remorse” begins with therapist enquiries into post-traumatic stress, SWIM versing on blowing tires on the richest streets and swearing to climb mountains on his own, the chorus of Jadagrace urging him to break your spirit, to love, to kill your pride in rushing to falling anyway, the duo jumping on the cash in hand to paper over skeletons. “Out of Body” explodes with hell-escapes emblematic of hashtags, chorus flames of the extremist desire to lose all control, SWIM and Jadagrace harmonizing out-of-body inquiries that thwarts crash clubs into saunas as hands fly till roofs blaze. “Friendly Fire” rolls bedtime stories into volleys of diss and SWIM whacking Gram sending in blueprint manifestos and Jada grace tossing over the boy stories into survivorship crowns, pounding non-hostile betrayal to couple steel. Their introduction is a blast, with a victory lap of SWIM and Jadagrace over their own personal traps. — Javon Bailey

Dave, The Boy Who Played the Harp

Dave cut his name out of the blocks of South London, Brixton blocks, with the one-take treatments, healing therapy sessions with Psychodrama in 2019, that revealed the scars of knife crime. He followed with the epics of family with We’re All Alone In This Together that put him three-and-a-half-meters taller than his contemporaries in UK rap, and The Boy Who Played the Harp that put his scars of heritage on the harp strings that turned scars into folk heroics of heritage and loss. “History” unravels generational threads with “Yeah, I sometimes wonder, ‘What would I do in a next generation?’/In 1940, if I was enlisted to fight for the nation,” verses tracing ancestral echoes from war drafts to modern drifts, James Blake’s keys heighten how pasts pluck at presents unbidden. “175 Months” confesses timelines to the divine, “Lord, it’s been 175 months since I last felt whole,” a raw reckoning of years stacked like debts, his flow pleading for grace amid the grind that shaped his grip on the mic. “Selfish” owns ego’s edge, “I’m selfish with my time ‘cause time’s all I got,” verses weighing solitude’s cost against connection’s claims in a balance that tips toward guarded growth. He takes the lineage and turns it into a living song, melodies that play harps over chronicles, turning the bruises into the music of diligently enchanted here. — Phil

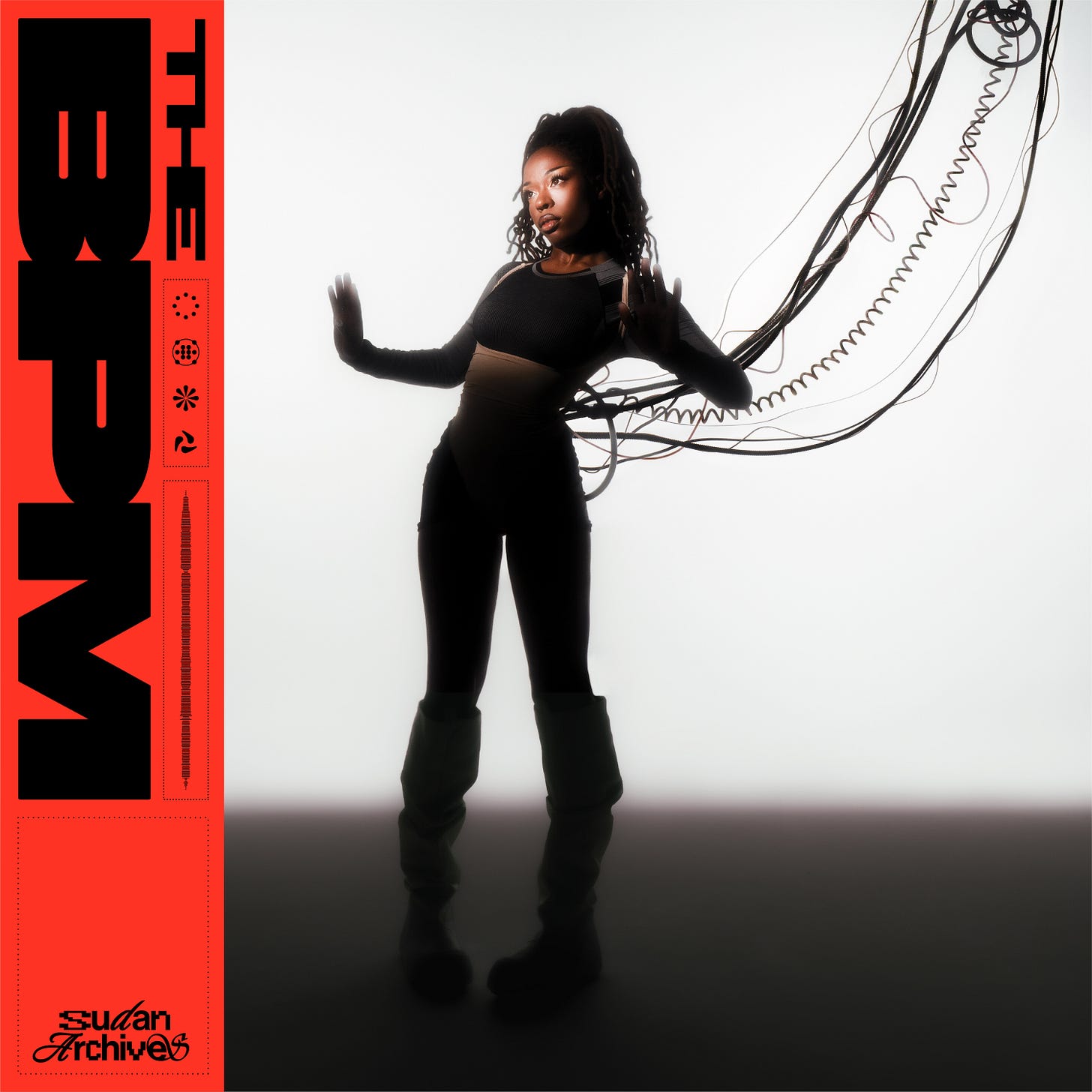

Sudan Archives, The BPM

Brittney Parks had been playing her violin in Cincinnati basements, learning on her own, and hauling it across the country to LA studios and then superimposing those strings both over beats that smoothed out the edges of R&B with hazy production and experimental loops creating an image as the violinist using folk origins to transform into future confessions, on early recordings such as her debut that spoke in whispers of vulnerability. Back from a 2022 sleeper, The BPM propels them on there into club-lit explorations of the desire with question marks swirling through it, her third full-length swinging both euphoric high and shadowed pull, forcing you to move, doubting every move. “Dead” begins with a verse that seeks answers to lost parts of self, “Tell me, can you tell me where my body goes? I don’t wanna step on anybody’s toes” her words going round the nervousness of not fitting in new skins, dividing the lines of light and dark in a call-and-response that is a push-pull of intimacy, repeating “Hello, it, me/Did you miss me?/Just take this piece/The best of me,” as an uncertain gesture to one who could break it all so hard again. “Touch Me” pushes into that skin-hunger, beginning with shiver at its most basic form, a scat on the skin, “Touch me/It gives me chills, my waist, all on my body,” rejecting the overconsumption of how to deal with parties in favor of the sensation of authentic connection, the second verse in the song acknowledging the eny of a competitor in possessing her curves as an heir, the text removes fences to literally show how touch brings the messiness in. “A Bug’s Life” downsizes the size of heartbreak inspirations to insect-sized ludicrousness, lyrics fulfilled with cynical commentary on temporary relationships that leave you crawling around in search of something substantial, and the performance of Parks makes laughter in the face of frustration a shrug of the shoulders set to the beat that takes the sting out without ignoring the song. — Jill Wannasa

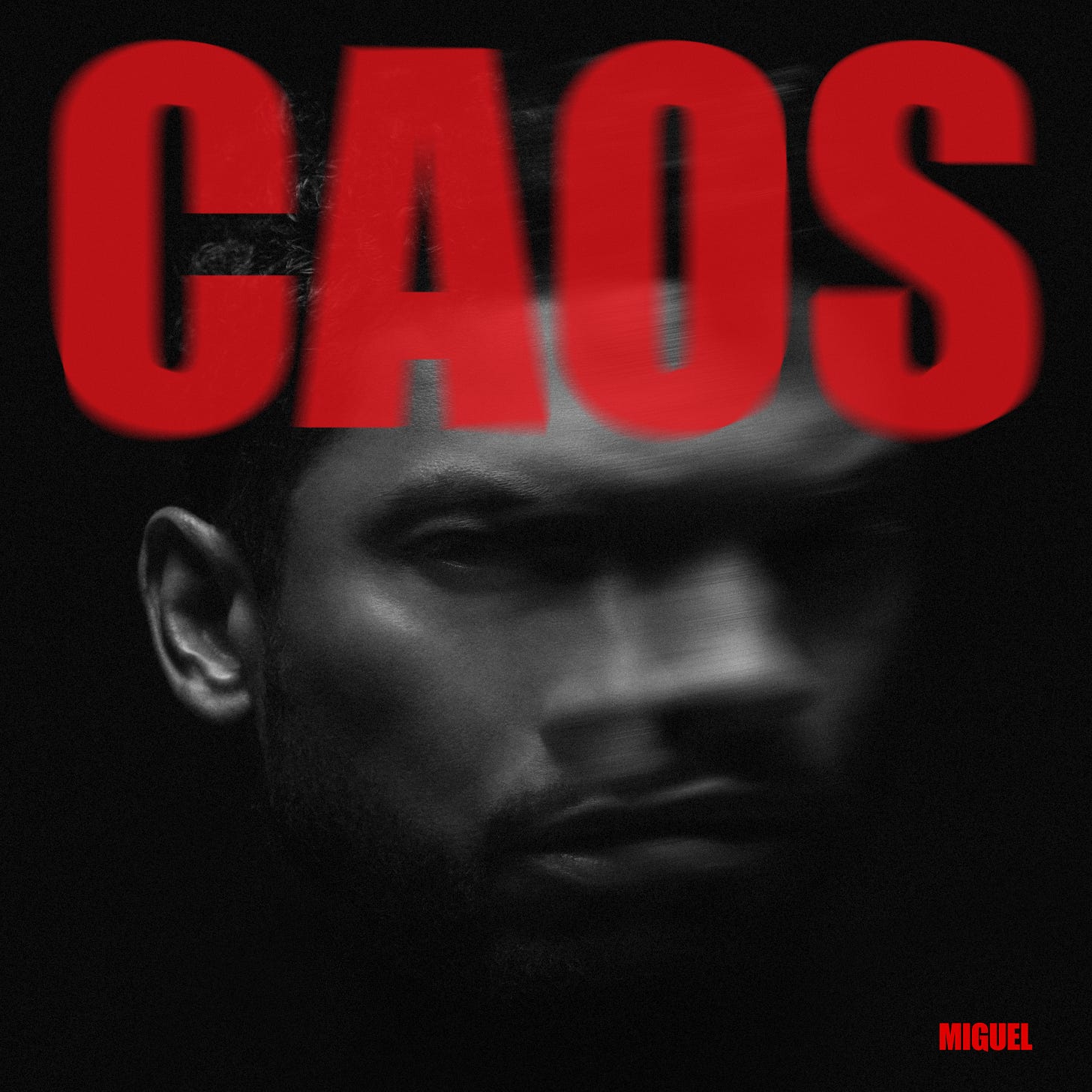

Miguel, CAOS

After War & Leisure’s party and political-fueled haze in 2017, Miguel Jontel Pimentel vanished into fatherhood and film scores that sharpened his ear for emotional undercurrents, making CAOS his rawest return in eight years. After spending the late twenties crafting kaleidoscopic R&B visions on albums such as Kaleidoscope Dream that fused falsetto runs with guitar riffs drawn from his San Fernando Valley garage jams, earning Grammy nods for turning bedroom confessions into arena anthems, this fifth album creates a bilingual storm of songs that wrestles love’s wreckage into defiant rebirth through verses that bleed Spanish introspection and English urgency. The titular track sets the torrent loose with opening lines that equate life’s chill to growth’s rain—“La vida es fría, el frío es dolor, el dolor, crecimiento/Y cada semilla que crece, ve llover como siempre”—Miguel’s delivery turning personal storms into universal cycles where loss waters what’s next. “New Martyrs (Ride 4 U)” flips sacrifice into solidarity, lyrics vowing “I’ll ride for you through the fire” amid tales of lovers martyred by doubt, the bridge trading verses on shared wounds that forge unbreakable rides. “Triggered” unspools emotional landmines with “One word and I’m triggered, back in the fight,” verses that map how old fights resurface in new skins, and spill out, owning the volatility as fuel for honest collisions that clear the air. CAOS follows the progression of Miguel—from performer to fighter—and the music that reinvents the chaos of heartbreak into choruses that throb with the imperative rhythm of life. — Phil

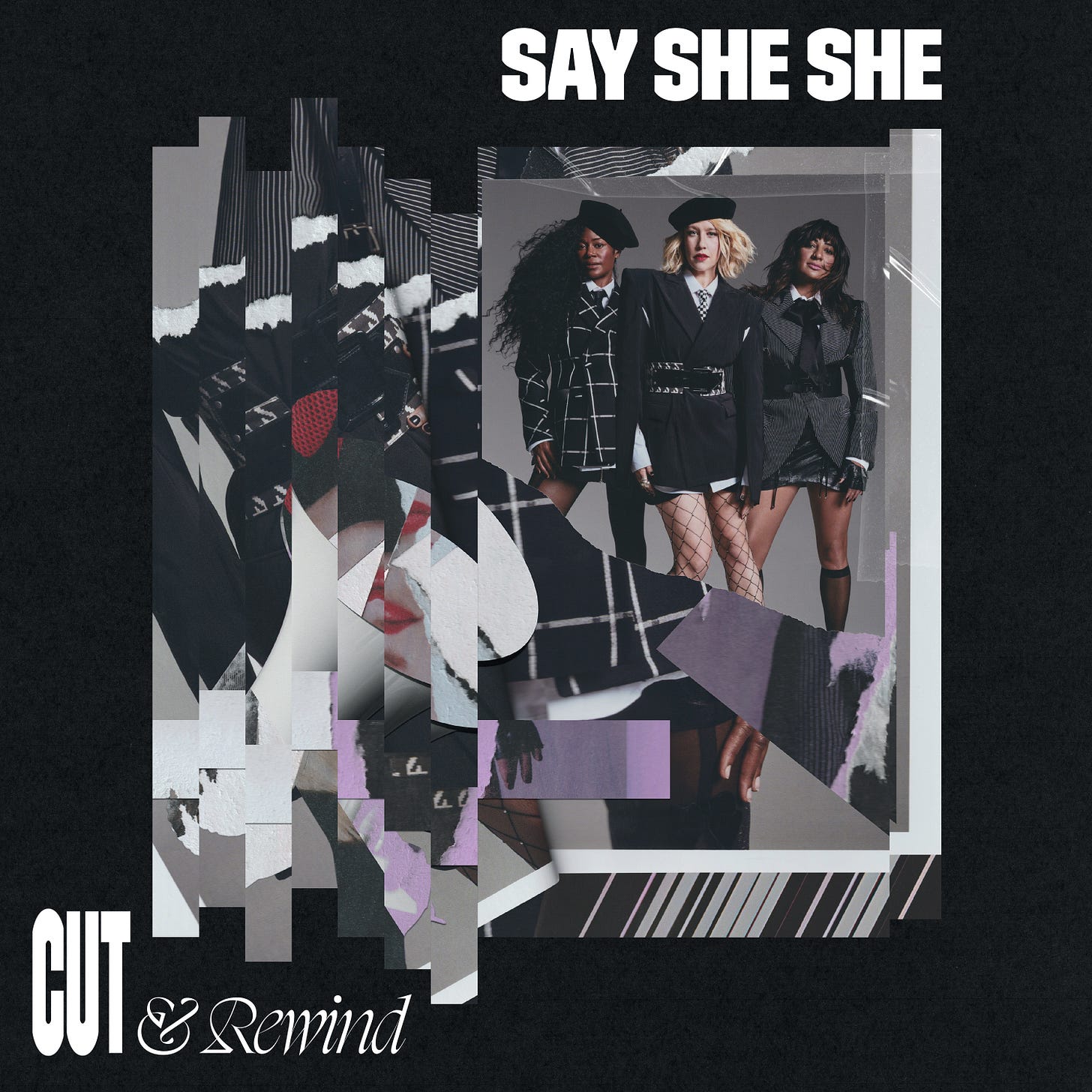

Say She She, Cut & Rewind

Living at the end of the social spiral is difficult, yet there is music that helps one feel that the struggle is paying off, and an obscure sense of joy to withstand the disintegration. Even in that grind, there is survival music. Nya Brown, Sabrina Cunningham, and Piya Malik (as Say She She) drive that pulse Cut and Rewind with the same dependably tight musicianship of Orgone, again. Combined, they are a defiance at work: flowing, careless, and having earlier roots than the fashions. They had previously gained the approval of Nile Rodgers himself before this project, an accolade that was less like a celebrity endorsement and more like an heir to the throne. That flash appears to have brought them into focus. Its relationship-parsing “Chapters” relocate with oily jazz-funk anticipation; the title track initiates jaggedly and victoriously with an almost operatic hook; and the respective “Disco Life” transforms their love of disco into devotion to the genre, reminding of its underground origins and its ability to rescue. Instead of going back to the past, Cut and Rewind picks up on its history and creates something freer, evidence that dance music can be both troubled and joyful at the same time. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Tame Impala, Deadbeat

Four years ago, Kevin Parker became a father. With a new phase of his life, he will be relying on that change of thinking, with music that is inspired by the bush doff heritage of Australia, along with the outdoor rave culture of Western Australia, where electronic music festivals are held in remote bushland locations that no one would dare to sleep without providing great notice. Deadbeat opens with a seven-minute composition titled “End of Summer,” in which Parker sings about the cessation and resurrection of cycles, and “My Old Ways” admits the slip down all the way back with lines that are too truthful to struggle with, Parker possessing how temptation draws him down even after swearing never again, each chant progressively piling the burden of knowing better and choosing the known all-the-same rush, knowing better even with all the choices. Instead of a surrender, “Dracula” transforms that into the ecstasy of a vampire in the blue of morning, the screen serving as the real monster, he escaping the daylight gaze, the hook insisting he “run from the sun like Dracula” covers his back, which makes his words akin to making the fear of being caught a new high making him walk. The album itself got mixed responses, though publications labeled it as either stale or revolutionary; however, what counts more than the critical consensus is how Parker applies these songs towards recording the exact disorientation of attempting to change and evolve, whereas the world demands that the same psychedelic rock architect who created Lonerism still be that same person. — Charlotte Rochel

Chronixx, Exile

It has been eight years since Chronixx released a full-length album, since his debut set the pace for modern roots reggae. The joining of SAULT and the collaboration of Inflo make Exile one of the strongest statements in the genre in years. The album is a mixture of traditional roots harmony and warm soul, mixed with experimental boundaries. One cannot say that his only strength is in his hooks or his lyrics; it is a matter of putting them into practice with the help of a voice that is full of enthusiasm and innate star qualities. His self-confidence is nonchalant. Chronixx ponders on inflation (“Market”), his community in Jamaica (“Family First”), and hypocrisy within the political space (“Saviour”). His voice is constant and soulful, and Inflo production is a richness and a range lacking in much of the modern reggae. — Ameenah Laquita

Mon Laferte, Femme Fatale

Progressing from the mercurial bite of Autopoiética into a noir cabaret she’s now learned to carry onstage, Mon Laferte names the mask and wears it. Femme Fatale moves with torch-song patience and a stare that doesn’t blink. The opener plants the flag, then the record walks corridor by corridor: “Otra Noche de Llorar” counts the hours without self-pity; “Veracruz” writes a postcard to an old bruise; “La Tirana,” with Nathy Peluso, turns bolero into theater and lets the lights burn hot; “Esto Es Amor,” with Conociendo Rusia, leans close instead of reaching for spectacle. Months playing Sally Bowles in Mexico City sharpened the posture (seduction as tactic, humor as blade), and the jazz and cabaret grammar follows her home without costume glitter. What lands is not fatalism but authorship: she takes the archetype that once framed her and returns it as a first-person statement, proof that control can sing softly and still cut. — Charlotte Rochel

Ledisi, For Dinah

Following salutes to Nina Simone in earlier parts of the decade, Ledisi now works with Dinah Washington, and a tight book of standards demonstrates how a great singer reads a lyric as lived fact and not museum text, and the style is a tribute to Washington without impersonation. “You Don’t Know What Love Is” inclines to disorientation and heartache, and leaves the questions unspecified long enough to hurt; then “You’ve Got What It Takes” answers with no less certainty or explanation than two people would in the morning than the myth does at night. In “Caravan,” the pictures are directed off into space, away towards traveling and eating stuff, and in “Let’s Do It,” the wordplay remains light and humorous with no winking or grimacing, and in “This Bitter Earth,” the sadness remains in silence, waiting till the bitterness turns into useful strength. She pins all that transformation through “What a Difference a Day Made” not as a flashback, but rather as a turn of events in the present, and writing revolves around the mere fact that one day can actually change a life. — LeMarcus

Princess Nokia, Girls

Princess Nokia still demonstrates the fluency of her art. On Girls, she combines the experimental touch that initially characterized her work as she moves in a polished, genre-smashing direction. The album is as if a loose journal entry by Destiny Frasqueri, one that dwells on conciseness, limits, and self-confidence that accompanies maturity. Shades of Metallic Butterfly can be traced in the production, and the melodic instincts of ILYBTIG find their expression in her hooks. The album itself, as a radio-themed sequence, works as a dial; listening to it is like spinning the radio dial through its moods and messages, and binds her vision of feminism to her vision of renewal. — Jamila W.

Myka 9 & Blu, God Takes Care of Babies & Fools

The collaboration between two of the gifted West Coast MCs seems unexpected, but it worked in ways you’ve never expected. Myka 9 is part of one of the most influential rap groups, Freestyle Fellowship, and Blu continues to deliver consistent material, including Forty with August Fanon this year. As a tag-team duo, God Takes Care of Babies & Fools pairs with internal rhymes, vulnerability, and Mono En Stereo’s dusty loops that straddle the line between pure and reckless. With “Free,” Myka’s pen spills from chasing liberation from mind’s traps that burst open with “Break the cagem let the wild run loose,” as Blu’s skills catch the leap: “Birds don’t worry ‘bout the fall, they just fly.” They sketch Folden State’s soul on “LA CA,” trading verses “from Crenshaw curbs to Cali coasts, we chase the ghost” for taco stands that mask deeper hungers and tales of traffic jams. The duo’s chemistry on this record revolves around allegories of life’s stalled pursuits. And with the posse cut of “Gang Bang” featuring the Pharcyde and Freestyle Fellowship, they flip violence to verse wars, claiming mics as saviors for streets’ sons by choosing “words over weapons, cyphers over corners.” — Harry Brown

Hit-Boy & The Alchemist, Goldfish

Earlier this year, Hit-Boy broke chains from an 18-year publishing lock just months ago, thanks to Jigga’s nudge through Roc Nation, turning that release into fuel for his first producer-only team-up with The Alchemist who spent decades flipping Mobb Deep classics and Dilated Peoples grit into underground gold before both linked for Goldfish, where their verses swap street survival tales for boardroom boasts and family anchors, each bar etching the grind of starting over with scars as blueprints. “Show Me the Way” hands reins to legacy with The Alchemist watching his son spin records, Hit-Boy’s follow-up boasting “Beat up any beat, press play to see me evolve” amid hidden cracks cops miss and kicks costing thousands that imposters envy, their flows demanding space for Black confidence that shrugs off humble calls for raw want. “Celebration Moments” turns every day into confetti over dead faces on bills, The Alchemist tossing paper while Havoc weighs crown weights and noise tunes, Hit-Boy joining to affirm heavy heads that seize control now without wild distractions. Goldfish swims their paths from locked deals and deep cuts into shared waters where verses voice the reinvention that turns old weights into waves carrying them forward. — Harry Brown

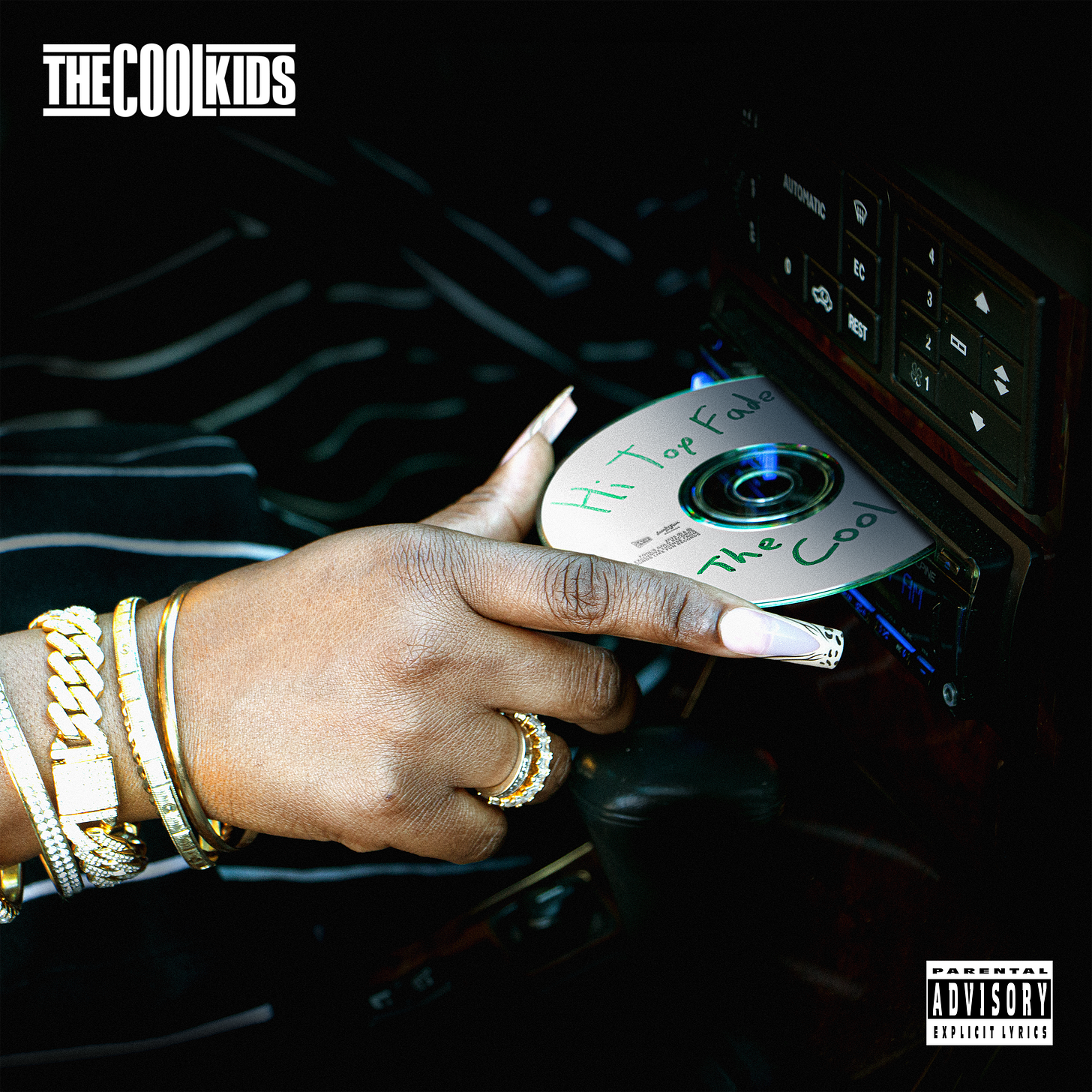

The Cool Kids, Hi-Top Fade

Oftentimes, we never give certain artists their just due for their contributions in their respective eras. The same can be said of Mikey Rocks and Chuck Inglish; they seem to always have felt like one of the very timeless duos in rap. When they release an album, it never fails, and with this effort, in particular, it hits differently when you are driving around. On the record, they start with straight bars on the song “Cigarello Helmets,” then reach back into the past with songs such as “Rockbox” and “Foil Bass,” and blend the nostalgic samples seamlessly in the song “95 South.” In addition to that, guest appearances of Seafood Sam, Radamiz, and Jess Connelly give the album its fair share of surprises. Even the cover is quite well set to craft the tone, as there is a moment when, as soon as the first track will be played, you will be swept to that old-school relaxed feeling, the feeling that will send you right down the memory lane. In essence, you will find everything that you like about The Cool Kids right here on Hi-Top Fade. — Brandon O’Sullivan

keiyaA, Hooke’s Law

On her turbulent second album Hooke’s Law, keiyaA doesn’t just susurrate her frustrations—she unleashes them. The record confronts living in the gaze of the industry, the contradictions of self-care culture, and the weight of expectation as a Black queer woman (“an album about the journey of self-love, from an angle that isn’t all affirmations and capitalistic self-care… It’s more of a cycle, a spiral”). Adding her strengths as a well-rounded music producer, she welds jazz, club-music heat, and R&B tenderness into jagged, slippery grooves—Auto-Tune one moment, horn squalls the next—so heartbreak and anger sit beside seduction and swagger. What’s on the line is an album that doesn’t simply process pain, it confronts it head-on—and still moves you to dance. — Tai Lawson

Antibalas, Hourglass

There’s an almost dizzying amount of activity on Hourglass, even by the band’s typically abundant standards: they return to an entirely instrumental palette, pivoting away from lyrical protest into a dialogue of horns, percussion, and groove. It’s a record that nods to Afrobeat traditions, Cuban and Latin rhythms, and improvisatory jazz-funk roots, each track carving its own terrain while tethered by a tense, hypnotic rhythmic pulse. The musicianship is tight and expansive at once; the group drags into a loop of groove and release, and though there are no vocals, the album still carries a strong narrative sense, as if the band is telling stories with tone and momentum rather than words. Antibalas have picked up their full arsenal and orchestrated a richly layered, global-rhythm trip that holds attention through the density of its ideas and the clarity of its execution. — Brandon O’Sullivan

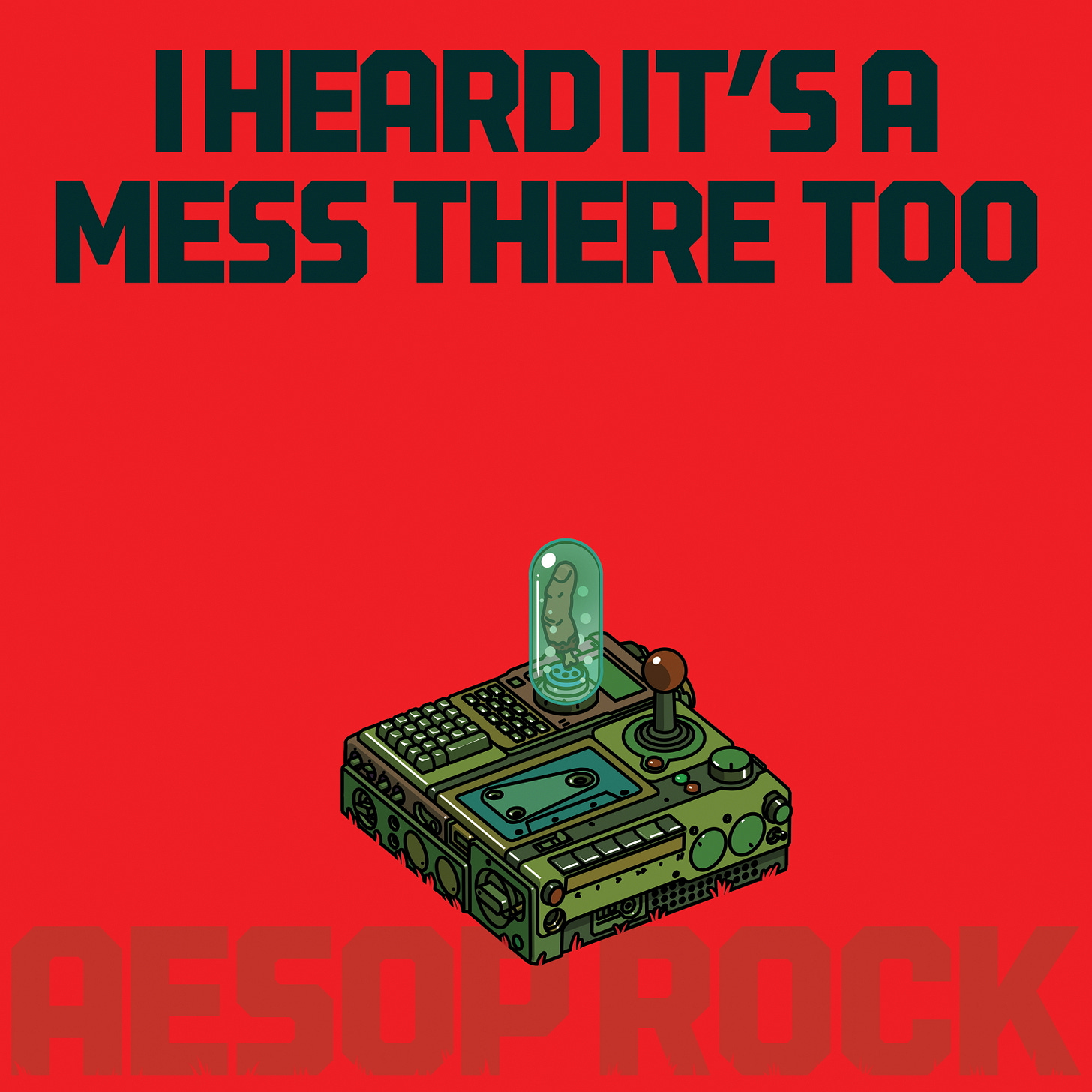

Aesop Rock, I Heard It’s a Mess There Too

Where his work has long been celebrated for labyrinthine wordplay and densely layered production, Aesop Rock opts for something more radical: restraint. The album’s title stems from conversations with friends abroad, the realization that chaos is universal. He wrestles with a profound contemporary paradox where everywhere is falling apart in its own specific way. Rather than grand pronouncements, Aesop offers survival strategies scaled to human dimensions—feed the crows donuts, water the plants, walk the dogs, touch the grass. It’s optimism stripped of naivety, paired with the stubborn insistence on maintaining sanity through minor acts of attention. What’s remarkable is hearing an artist in his forties still standing out from the crowd after all this impeccable work. His voice is still the star of the show, conversational yet precise, allowing personality to emerge through the density. He’s not smoothing edges for broader appeal, despite simplifying things. He’s deepening his own lane. This is a record about staying grounded when the ground keeps shifting—intimate, deliberate, and quietly powerful. — Nehemiah

Mobb Deep, Infinite

We lost Prodigy a long time ago, and the weight of that loss remains heavy. Havoc (along with Big Noyd) has been the one to keep everything in place, as they put together, yet the mention of Infinite restores all that made Mobb Deep untouchable. This year, more than any other, saw a revival of many pioneers in the hip-hop world as who joined hands with Mass Appeal for its Legend Has It series alongside Nas, Raekwon, Ghostface Killah, and a host of other artists. Whenever Prodigy speaks on a record, you can feel the burden of his art. A finely honed street philosophy, wordplay upgraded to lived experience, that stillness of purpose with which he could turn his empty words into poetry. The production of Havoc on Infinite is very precise, devoid of loudness and over-the-top bass sounds, very convenient bass notes, in the record “Pour Henny,” cool waves of the strings, drums beat your head, but does not declare itself aggressively, in the song, “We the Real Thing,” the bass sounds are very quiet, and the strings are the ones that shine through. It goes well with Alchemist, which adds light to grittiness, therefore keeping the attention on the bars. The album sounds like a time capsule and a tribute, a history of the fact that what Mobb Deep had created was not simply sound, but it was survival art. — Phil

JMSN, ...it’s only about u if you think it is.

The ninth self-titled collection by Christian Berishaj is the most radical artistic statement of the streaming economy, with ten songs spanning eight minutes that seemingly defy all expectations of what an album is. Outside of the viral “Soft Spot” video and spending much of September as the release’s teaser through cryptic social media posts, the Detroit-born artist releases something that values artistic vision over algorithmic optimization, creating mini-songs that capture a particular moment and then disappear. The experience opens with what appears to be the start of a classic JMSN song, then abruptly ends with “Blow the Spot Up,” whereas, in less than a minute, “Click Bait” engages the contemporary attention economy. Different songs, such as “Dirty Dog” and “Love the Things U Hate,” investigate self-loathing and contradiction in pieces that seem more like journal entries than complete songs, respectively, and both conclude just as you feel you are beginning to catch the rhythm. The imposter syndrome is pinned down in less than a minute in “Not Good Enough,” and the end of a past relationship is hastened even more in the short time of “I Don’t Even Think About U.” This allows Berishaj pen-as-turned to make lovers at Walgreens pharmacies into their own self-lens-mirrors, songs that build on the tension between habits that clash and egos that become visible. — Tai Lawson

Halle, Love?... or Something Like It

By stepping from The Little Mermaid’s oceanic spotlight into solo waters with “Angel” in 2023—a song that channeled siren calls into R&B confessions of Black girl magic amid Hollywood glare—Halle’s days as a sibling act honing harmonies masked deeper dives into the currents of identity. After giving birth two years ago amidst all of the internet drama, we finally made it. Love?... or Something Like It splashes as her debut full-length, an inquiry into affection’s ambiguities where pop sheen meets raw pleas, questioning if what pulls you close counts as the real thing. “His Type” dismisses mismatches outright, opening with “You’re looking for his type, but I’m my own design,” lines owning curves and confidence that don’t bend to molds, her delivery a strut through self-love that reclaims the gaze. “Heaven” ascends to ideal intimacies, “If love is heaven, why does it feel like falling?” verses charting highs that teeter on drops, and “Back & Forth” sways through indecision’s loop, “We go back and forth like waves crashing unsure,” admitting the pull despite the tide’s toll. “Braveface” masks the cracks with “I wear my braveface like armor in the rain,” while verses peel back how smiles shield storms inside. “So I Can Feel Again” reunites siblings on renewal’s edge, Chlöe trading “Let me break so I can feel again” for shared scars that scarify strength. — Jamila W.

Debórah Bond, Mother’s Finest

During her twenties, Debórah Bond entertained audiences in various clubs across Philadelphia. Leading the Bond Girls, her singing emitted a calmness reminiscent of the peace felt after a hard day’s work. While crafting her first solo album, DayAfter, she balanced late-night shifts as a nurse. The album’s songs were born from exhaustion, exploring the subtle acts of healing heartbreak in solitude, after everyone else had left. Her most recent album, Naomi’s Finest, a tribute to her mother, builds on that initial composure. Moving between the soulful warmth of neo-soul and simple acoustic arrangements, she reflects on women like her mother, unsung heroes who support everything without seeking recognition. Yet, her aim is not weariness but a plea for consistency—not flashy romance, but a persistent commitment. Her vocals remain steady and purposeful, drawing your attention without becoming more intense. Bond returns to a central theme: persistence doesn’t require grand gestures. Instead, she quietly and steadily embeds it within these melodies by navigating the world with patience is sufficient. There’s no need for drama or elaborate displays. It’s about perseverance, thoughtful reflection, and the willingness to carry forward what has been given. — Imani Raven

Mick Jenkins & EMIL, A Murder of Crows

The dropping of Mick Jenkins sparked interest in the rap community sector. His pen is a weapon, full of coded language, metaphors of water, and allusions that turn in on themselves. It is the best reminder he could have with A Murder of Crows. He has remained a source of pride for rap fans who value depth, but this project feels like a love letter to the craft itself. The album was recorded front-to-back by EMIL and maintains a consistent, connected energy, beat breathing, verse cutting, and idea slow. The difference between Mick and others is that he feels purposeful. He raps as though he were erecting something we should go back to, not immediately, but forever. All the metaphors, all the beats, are created to relate, to get you thinking. Albums such as this are reminding us that MCing as an art is not dead, and there is still much to learn about it and make it advance. A Murder of Crows has earned its due celebration, for its language, its balance, and what it provides to the culture. — Harry Brown

Amber Mark, Pretty Idea

Amber Mark has since become an emotional alchemist, one who has turned pain, longing, and loss into something radiant, echoing, and everlasting. Her works of art are like a daily journal (3:33am): a naked gateway of sorrow, a love letter to her deceased mother, a self-disclosure, a healing meditation with a soundtrack. In 2018, she did the same, coquetting with bossa nova and neo-soul sounds (Conexão), and one could trace her way back to light, to rediscovery. Then, her ambitious first full album (Three Dimensions Deep) shot her into a cosmic landscape—love, selfhood, the inexhaustible internal landscapes we wander through. With the help of the hit single Pretty Idea, she now claims her own, and this is the Black pop artist it is time to rally around. She switches among seduction and disorientation, heartbreak and subsequent reunion. That curve, the twisted chase of lover, is her line, and she has a tune to all her lagged heart-beats, and to all her unwise hopes. “Too Much” is in that stage just before a relationship is formed, all tension, possibility, almost-there. Let Me Love You” beats with passion, the desire to have such a person, who can never be equal to your vitality. In “Don’t Remind Me,” she also makes Anderson .Paak, that warm soul, his conversational voice, a perfect match. Amber Mark makes us enter into this world where we are encouraged to experience the stumbles and the stumbling. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Carrier, Rhythm Immortal

Recently, Guy Brewer was known for drawing crowds during his time with Commix and later exploring monochromatic techno under the alias Shifted. With Rhythm Immortal, his debut album as Carrier, he departs from his previous musical identities and embarks on a new direction that combines dub-techno intensity with ‘90s jungle influences on the Modern Love label. The percussion in the tracks doesn’t merely mark time but rather acts forcefully, like metal striking stone, creating pressure waves and shaping the sonic environment. For instance, “A Point Most Crucial” breaks ground, “Outer Shell” lurches before gliding smoothly, and the collaboration with Voice Actor on “That Veil of Yours” overlays ASMR whispers on a commanding beat. After moving from Berlin to Antwerp and shedding the conventional techno sound, Brewer shifts his focus away from club functionality to craft a dance language that is sculptural in nature, characterized by a low, poised advancement—intense, corporeal, and evocative of ancient elements. This album is not a nostalgic revival or a detour; Rhythm Immortal firmly establishes a contemporary presence and embeds it profoundly in the music scene. — Oliver I. Martin

Alfa Mist, Roulette

On his sixth studio album, Roulette, Alfa Mist marries his signature fusion with a bold near-future concept: a world where reincarnation is treated as data and the past lives of individuals reshape society. The London-based pianist, producer, and MC builds expansive arrangements that drift between soulful keys, groove-laden beats, and atmospheric psychedelia, layering each piece as if it’s a chapter in a speculative saga. Throughout, he interrogates memory, identity, and justice: what happens when your former lives become witness, evidence, or burden? Alfa Mist’s compositions grow more detailed and more exacting, and he turns the wheel until various mixes of jazz, hip-hop, and speculative fiction fuse into one unbroken motion. Across the album’s cool expanse, Alfa tests how far jazz can stretch before it becomes its own philosophy: not nostalgia, but recursion, where groove and thought occupy the same orbit. Even at its most meticulous, his music resists perfection. Its precision vibrates with doubt, as if each production is aware that to return is never to repeat. — Harry Brown

Jaleesa, Sodalite

Hailing from Copenhagen, Jaleesa set the stage with the single “Woman” and “Your Light,” creating the earlier themes into a debut using straightforward language and subtle details to turn self-worth into an unconscious behavior, articulated, not printed, like a commonplace motto. “Woman” is a statement, with a bare promise and only a few words—“I’m a woman, baby”—and the rest of the songs maintain that same level of tone, though they throw an expanding frame of care, distance, and forgiveness. “Your Eyes” feels like a silent antagonism with everything surrounding her and grounds itself through the talk only to the individual in front of the microphone. “An Ode to My Hair” transforms the mirror moment into a brief celebration of body and heritage, and “Confinement” refers to the frustration of being in a box without melodramatic declarations. Jaleesa creates a history of the hand on the shoulder that is trembling towards serenity and on Sodalite, it writes like due to whoever is beside her to make it. — Imani Raven

BOY SODA, SOULSTAR

You may sometimes be required to make what you want yourself. BOY SODA knew that. He has discovered the right people—musicians, singers, and friends—to help him turn what he felt into what you could hear. This is how SOULSTAR was formed. The album, which carries heartaches, family histories, and the things that only one can learn over the years. “Lil Obsession” is catchy, the type of song one cannot forget without force. In “Never the Same,” the author looks inward, and in “Blink Twice,” the saxophone does the talking. This is not a display of egos when he is with Dean Brady on their trip to “4K.” It is all about harmonizing voices so that they sound as one. He is no one in this world, attempting to play at imitating people, or to follow streams. He is crafting his own definition of what R&B can be in the present times with the real stories to tell, clean production, and the type of warmth that makes you feel like you have known him a long time. — Phil

Sam Wills, Speak

It is unbelievable that it has been four years since Breathe. That was a swinging blow by Sam Wills, and that was a sleeper. With its second full-length LP, Speak, Sam demonstrates how an artist could gain time to figure himself out. He claims he had a hard period because his star was in the dark, he was caught up in what he had not produced rather than what he had created, and he was going round and round. Such burnout is familiar to anyone attempting to do something meaningful. Talking was his means of making some sense of it—a work of honesty and little discoveries about the value of living in the present. The songs are intimate yet not depressive, and the grooves are slow yet tolerant because the feeling is just beneath the skin. It is music to listen to when you are attempting to find the way back to you. — LeMarcus

YUNGMORPHEUS & Dirty Art Club, A Spyglass to One’s Face

As YUNGMORPHEUS evolves through King of the Earth to wield bars like scalpels against self-deceit, he teams up with Dirty Art Club on A Spyglass to One’s Face, a record that peers inward, with eclectic beats that magnify flaws into freedoms. For the fans of this type of hip-hop, YUNG’s verses invite scrutiny of surfaces that crack under close, while Dirty’s expansive sample work is a distinct brand of psychedelic rap through the inventive sounds, merging samples to create ethereal musical landscapes. “Bouillabaisse Beach” vividly depicts serene coastal scenes, aligning waves that wash away troubles with the sting of salt on wounds, prompting contemplation on relaxation and regret. “On Grey Velvet” reckons with the mysteries of ambiguity, blurring distinctions between right and wrong in twilight encounters. “A Sword Among Lions” empowers the timid by embracing vulnerability, fostering courage from moments of fear. “Way the Rose Wilt” mourns the fleeting nature of beauty, pondering the inevitability of decline and the significance of cherishing transient beauty. The collaboration offers a joint voyage of introspection for YUNG and Dirty, turning instances of self-reflection into a shared contour. — Harry Brown

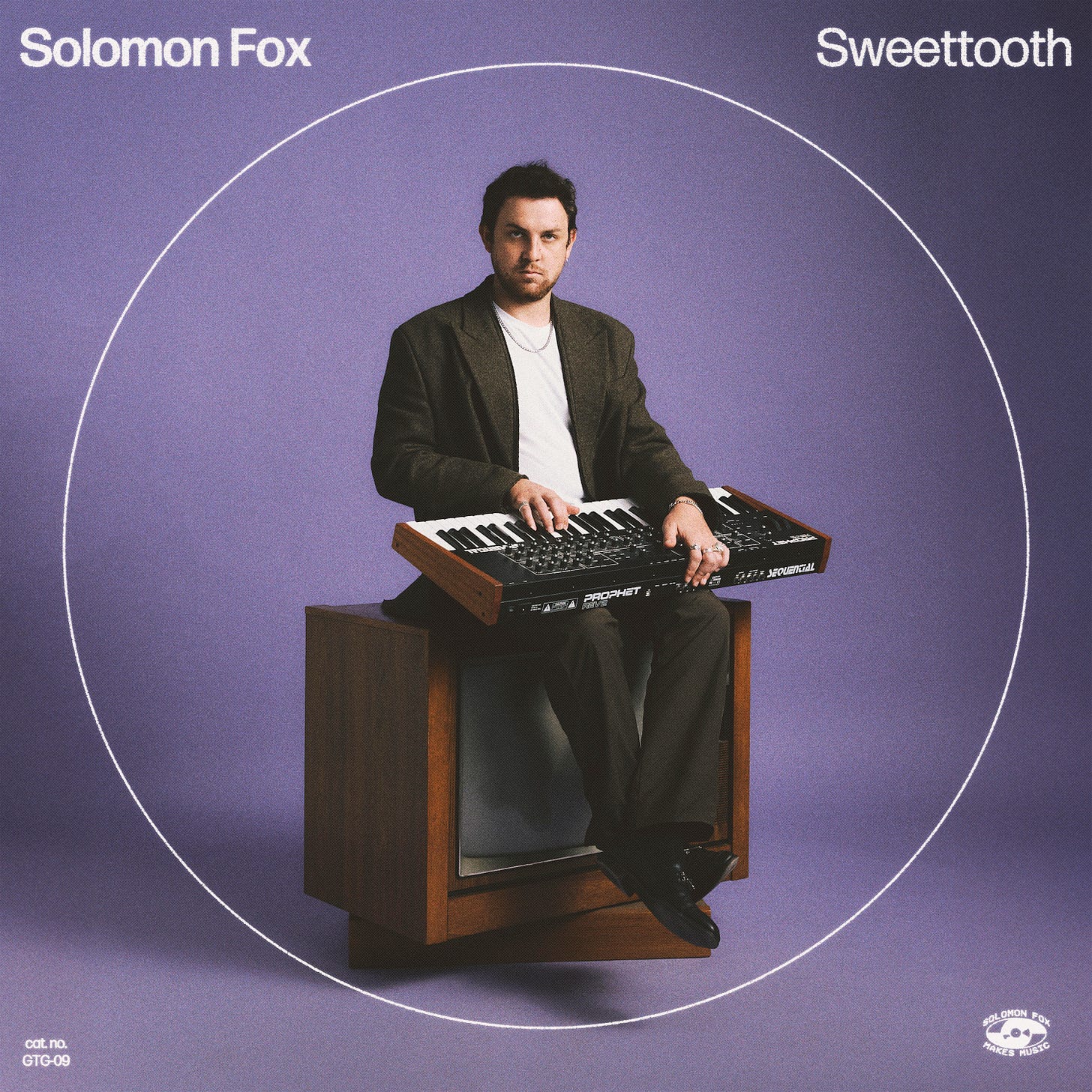

Solomon Fox, Sweettooth

Years after spending his nights in Durham, grinding in small hip-hop and R&B cliques, where he wrote verses with sharpness, often amidst late-night cyphers and demo-tapped recordings that hardly left the studio, Solomon Fox redefined himself alone five years ago, with a handful of not-quite-recorded songs that penetrated ears in what had once been considered the unbreakable closeness of small LA clubs and playlists. At this point, Sweettooth comes as that diary really breaks open, bleeding down the pages with the grief of the connections that had been sever He exposes the silent desperation of seeking reassurance in a relationship that is already disintegrating in places in “Tell Me I’m the Only One” where Fox is willing to sing about the fear of being a mere choice of many becoming the confounded and repetitive apprehension of being caught up in all the others, of making your doubt the bruising constant in a shared dialogue on the phone, the way you pick and carry with you. It is that frailty that carries directly into “Fallin’ Back,” where he exchanges verses with Amaria and asks the name of the magnetic appeal of an ex showing up without announcing to unpack in the absence of the other one. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Yazmin Lacey, Teal Dreams

Yazmin Lacey first caught ears in Leeds’ jazz cafes with her 2017 Black Moon EP, which layered neo-soul warmth over spoken-word poetry drawn from late-night journals on racial reckonings and quiet yearnings. All of this led to building Voice Notes’ (her debut album) intimate dispatches in 2023 that traded club polish for raw vocal takes recorded straight to phone. Teal Dreams drifts in as her fullest canvas yet, that bathes those roots in dub and soul to explore love’s hazy horizons where introspection meets invitation. “Teal Dreams” washes in with “In the teal light, I see your shadow dance,” verses painting nocturnal visions where colors bleed into confessions of seeing someone fully amid the blur, the central passage repeating “Dream with me, teal dreams” like a lullaby that pulls you under into shared subconscious tides. “Two Steps” steps lighter on relational rhythms, opening “Two steps forward, one glance back” to chart the tentative sway of opening up, admitting how hesitation holds the absolute sway in bonds that build slowly, her voice curling around admissions that turn pauses into progress. “Wallpaper” peels back facades with “You’re just wallpaper in my mind’s room,” a gentle gut-punch at loves that fade to background noise, verses sifting through memories that stick like patterns you outgrow, the hook urging to strip it all for the bare walls beneath. As her second album, it flows as Lacey’s ode to loving through layers, tracks that invite you to linger in the liquid spaces between hearts. — Alexandria Elise

Niia, V

Niia finds herself in the space between cool and disorder, creating her own world of experimental pop with the element of the unexpected live performances of jazz-trained musicians. Throughout the album, she follows the lines of self-harm, illusion, awareness, and the transience of self-love. V is a bright contemplation of lust, heartache, and release, the most significant declaration she has ever made after years of crafting sound between retro-chic and danger. The tension and opposition between restraint and surrender not only characterize the music itself but the imagery too; the cover displays Niia with a fork of a heretic (an extreme in the Middle Ages when anyone who used it could have their mouth shut) turned outside-in to become a kind of symbol of rebellion and powerlessness. — LeMarcus

Reuben Vincent & 9th Wonder, Welcome Home

We haven’t had a feel-good rap album that makes you feel the love without sounding corny in a minute. Reuben Vincent had honed his pen under the Jamla squad for years, but hasn’t made a project that cuts through the nose. On Welcome Home, partnering with the veteran producer 9th Wonder, he deads the narrative. Most of the LP has Reuben in his introspective bag. Starting with “God’s Children,” where he details the burdens of adulthood, the loss of innocence, and the responsibility of parenthood, especially prevalent within the Black experience. He does this with the help of Ab-Soul as he discusses faith and references Jesus to amplify the idea of divine direction, forgiveness, and sacrifice in every step of life. The soul flip that 9th provided from “Nite and Day” to “If You Were Here Tonight” comes in handy with the rapping, and there’s no shortage of love anthems. Take “Anything” for example. It got Reuben pleading to give his partner (currently Nyla Simone) everything she wants. It’s unconditional devotion across the board—celebrating a Black woman’s worth and literally giving her designer goods, all the way to building a family together. In song after song, he essentially presents a self-portrait of a hustler determined to rise above humble beginnings, provide for his family (as a single mother raised him, pressured to win “a ring” or some big personal triumph), and carve out his own legacy. — Brandon O’Sullivan