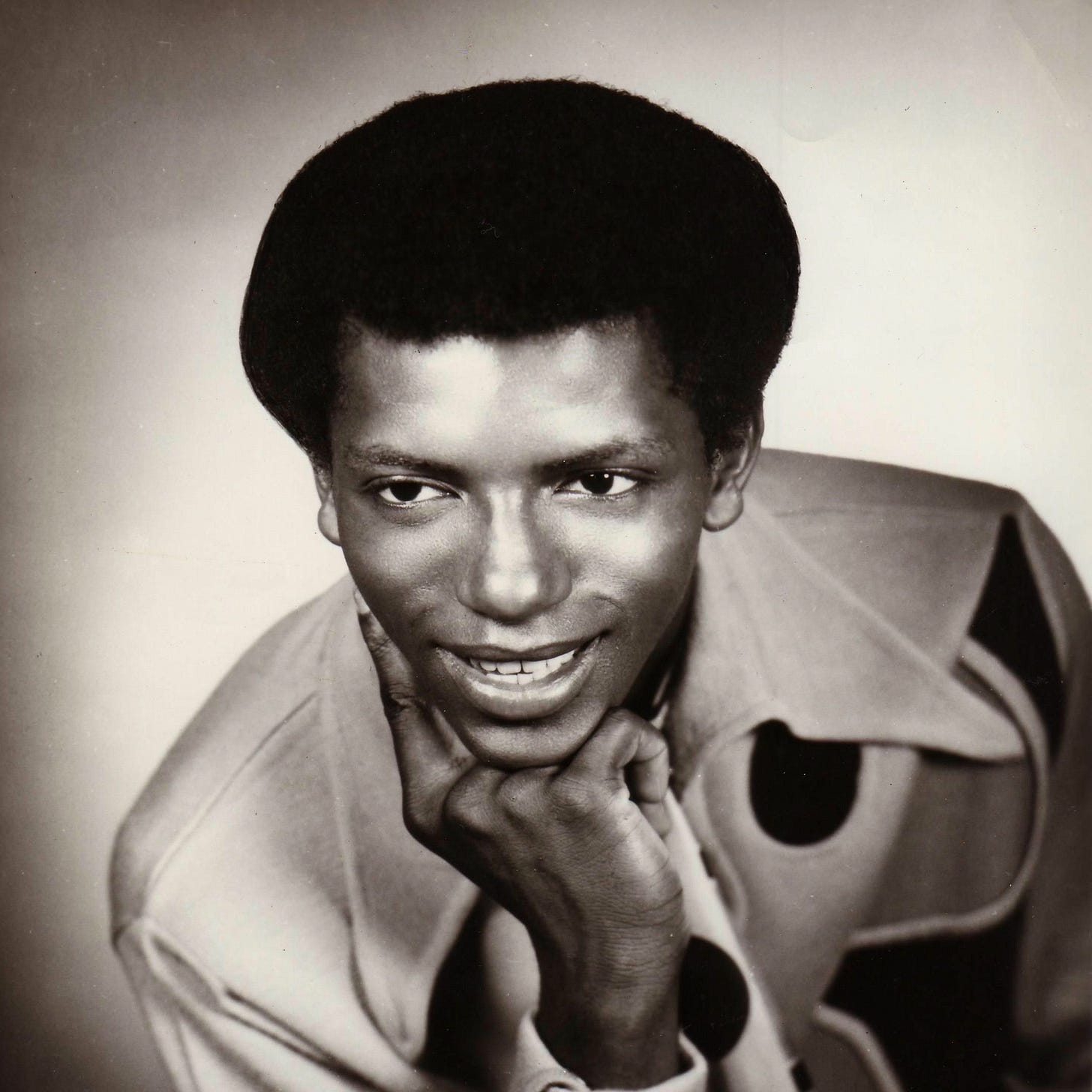

Our Tribute to Carl Carlton (1953-2025)

From Back Beat to bad mama jamas, Carl Carlton spent six decades proving that reinvention was its own kind of permanence. He sang everlasting love before he fully understood what everlasting meant.

Carl Carlton, the Detroit-born singer whose honeyed tenor powered two of the most enduring records in rhythm and blues history, died on December 14, 2025, in his hometown at the age of seventy-two. His passing closes a chapter of American music that stretched from the vacant lots of Black Bottom to the gold-record walls of 1980s funk, and the songs he left behind—“Everlasting Love” and “She’s a Bad Mama Jama (She’s Built, She’s Stacked)”—remain embedded in the cultural memory like fossils of joy that refuse to decompose.

The story of Carlton’s discovery belongs to Detroit’s mythology, a city where raw talent could emerge from anywhere and where neighbors took notice. Playing baseball in a vacant lot near his apartment building sometime around 1964, the eleven-year-old Carlton was singing along to a radio when a neighbor leaned out a window and demanded the kids turn off the music—only to learn that the voice filling the alley belonged to a child, not a record. That neighbor connected Carlton to Lando Records, a small Detroit operation where he cut his first singles under the billing “Little Carl Carlton,” a name intended to evoke comparisons to Motown’s blind prodigy, Little Stevie Wonder, whose early recordings demonstrated a similar precocious fire. The parallels extended beyond marketing: both singers possessed voices that seemed older than their bodies, instruments capable of conveying adult longing before either had experienced much of adulthood at all. Singles like “I Think of How I Love Her,” “So What,” and “Don’t You Need a Boy Like Me” circulated locally, establishing Carlton as a promising figure in a scene already overflowing with promising figures.

The trajectory shifted in 1968 when Don D. Robey, the formidable Houston impresario who had built Duke and Peacock Records into gospel and blues powerhouses, signed Carlton to his Back Beat label. Robey had founded Back Beat in 1957 as an outlet for secular rhythm and blues, and his roster included artists like Joe Hinton and O.V. Wright—singers who understood that soul music was church music with its collar loosened. Carlton relocated to Houston to be closer to the operation, a jarring transition for a teenager from Detroit’s dense urban fabric to Robey’s sprawling ranch, where Jersey cows grazed, and the pace of life slowed to a crawl between recording sessions and performances at Robey’s Duke Peacock club. His debut Back Beat single, “Competition Ain’t Nothing,” failed to crack the upper reaches of the American charts but became a revelation on the British northern soul circuit, where dancers in Wigan and Manchester embraced its driving energy as the soundtrack for all-night sessions fueled by amphetamines and devotion. Cash Box named Carlton among the best R&B artists of 1970, a designation that promised ascent even as the industry around him prepared to shift.

The breakthrough arrived in 1974 with a cover of Robert Knight’s 1967 ballad “Everlasting Love,” though Carlton’s version bore little resemblance to Knight’s original arrangement. Producer Papa Don Schroeder—the Nashville figure responsible for James and Bobby Purify’s “I’m Your Puppet”—transformed the song into a disco-adjacent declaration, layering strings and propulsive rhythms beneath Carlton’s pleading delivery. The reimagining worked: “Everlasting Love” climbed to number six on the Billboard Hot 100 and number eleven on the R&B chart, introducing Carlton to a national audience that had never encountered his earlier Back Beat work. What distinguished his rendition from Knight’s was an almost devotional desperation, a sense that Carlton was not merely singing about permanent affection but testifying to its necessity, treating the lyric as both romantic petition and existential claim. The expressive qualities that would define his legacy—a voice capable of tenderness and assertion in equal measure, phrasing that honored the song’s structure while claiming space for improvisation—announced themselves fully on this record, and the arrangement’s sophisticated sheen masked none of the emotional rawness underneath.

After its commercial peak, Robey sold his Duke, Peacock, and Back Beat catalogs to ABC Records in 1972, transferring Carlton’s contract to a corporate entity less attuned to the particular demands of cultivating soul talent. The relationship soured quickly: beginning in 1976, Carlton became embroiled in a royalty dispute with ABC that effectively froze his recording career, leaving him unable to cut new material while contractual obligations remained unresolved. He released a few singles during this period—“Ain’t Been No One Before You,” “Ain’t Gonna Tell Nobody (About You)”—that received favorable notices in outlets like Right On magazine but failed to generate commercial momentum, their underperformance attributed by some observers to the corporate conflict that shadowed Carlton’s every move. When his ABC contract finally lapsed, he resurfaced briefly on Mercury Records in 1977, releasing a single called “You You,” a lush ballad produced by L.J. Reynolds of the Dramatics, but the Mercury tenure proved fleeting, yielding nothing beyond those initial sides.

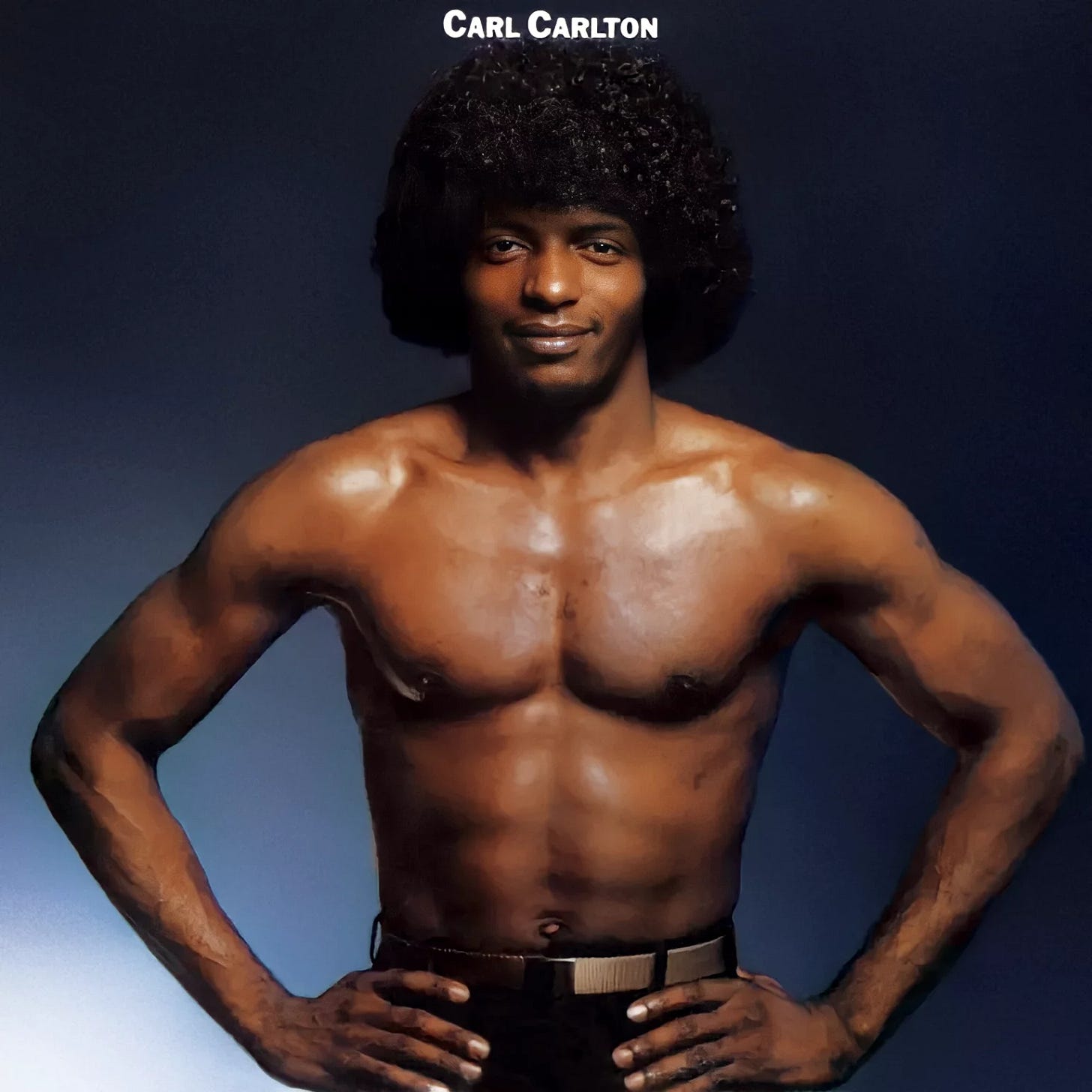

The wilderness years that followed might have ended Carlton’s story entirely, but the intervention of Leon Haywood—the Los Angeles songwriter and producer responsible for “I Want’a Do Something Freaky to You”—proved decisive. Haywood secured Carlton a singles deal with 20th Century Records and began crafting material suited to his voice and the changing sonic landscape of early-1980s funk. The first release, a cover of Haywood’s own “This Feeling’s Rated X-tra,” performed modestly, but the follow-up announced Carlton’s return with unmistakable authority. “She’s a Bad Mama Jama (She’s Built, She’s Stacked)” arrived in 1981 as a strutting, synthesizer-laced celebration of feminine confidence and male appreciation, its title phrase borrowing from Black vernacular tradition while its arrangement embraced the electronic textures that defined the era’s most forward-looking funk. The song climbed to number two on the soul chart, held from the top spot for eight consecutive weeks by Diana Ross and Lionel Richie’s “Endless Love,” and earned Carlton a Grammy nomination for Best R&B Vocal Performance, Male at the 24th Annual Grammy Awards.

The accompanying album, titled simply Carl Carlton, went gold, its cover featuring a shirtless Carlton displaying the chiseled physique he had developed during his years away from recording, when weightlifting and jogging alongside boxer Thomas “Hitman” Hearns had become his primary outlets. The success afforded him appearances on Solid Gold, Soul Train, and American Bandstand, as well as touring opportunities alongside Rick James, whose own brand of aggressive funk shared certain philosophical commitments with Carlton’s reinvented persona. The transformation from tender balladeer to confident funk architect demonstrated Carlton’s adaptability, his willingness to inhabit different modes of Black masculine expression as the genre demanded, never abandoning the vocal instrument that had first drawn attention in that Detroit vacant lot but learning to deploy it in contexts that would have been unimaginable a decade earlier.

The albums that followed through the 1980s—The Bad C.C. in 1982, Private Property in 1985—continued to generate minor R&B chart entries but failed to replicate the explosive success of “She’s a Bad Mama Jama.” The Bad C.C., recorded at San Francisco’s Automatt studios with contributions from Narada Michael Walden and Randy Jackson, included a well-received cover of the Four Tops’ “Baby I Need Your Lovin’” that reached number seventeen on the R&B chart, but the boogie-funk formula was beginning to show diminishing returns as the decade progressed. Private Property, released through Casablanca, produced a title track that charted respectably but signaled that Carlton’s commercial peak had passed. After 1985, he entered a prolonged recording hiatus, disappearing from studio work while the music industry underwent seismic transformations that left many of his generation struggling to find purchase.

The return came in 1994 with Main Event, a collaboration with singer Janet Jefferson that attempted to position Carlton within the new jack swing landscape without sacrificing his established identity. The album failed to chart, a casualty of an era that had little patience for legacy artists whose names carried weight only among listeners old enough to remember the original context. Carlton responded by pivoting toward live performance, joining the circuit of multi-artist R&B revue shows that kept golden-age soul musicians working even as their recording prospects diminished. His voice remained remarkably intact, capable of delivering the emotional payload of “Everlasting Love” and the playful bravado of “She’s a Bad Mama Jama” with conviction that suggested neither song had become mere routine.

In late 2002, Carlton appeared alongside Aretha Franklin, Lou Rawls, the Three Degrees, Billy Paul, and the Manhattans on the “Rhythm, Love, and Soul” edition of the PBS series American Soundtrack, a production designed to celebrate the architects of classic R&B before television audiences who might otherwise never encounter such a concentrated display of living history. His performance of “Everlasting Love” was included on the accompanying live album released in 2004, introducing the song to listeners born after its original chart run and demonstrating that Carlton’s interpretive gifts had only deepened with time. Throughout the 2000s and into the 2010s, he continued touring alongside fellow R&B luminaries on nostalgia circuits and festival stages, participating in revivals that celebrated soul and funk heritage while occasionally releasing independent singles that reflected his spiritual evolution.

The gospel turn arrived on August 1, 2010, when Carlton released “God Is Good,” his first venture into explicitly devotional material and a declaration that the voice once associated with romantic longing and funky celebration had found another register entirely. He followed with additional independent releases—“Saturday,” “One More Minute”—that circulated among devoted fans even as mainstream industry attention remained elsewhere. In 2011, he received a nomination for a Detroit Music Award in the Outstanding Gospel/Christian Vocalist category, recognition from the city that had first heard his gift echoing off apartment walls decades earlier. A comprehensive compilation, Everlasting: The Best of Carl Carlton, was released through Hip-O Select in 2009, gathering 22 tracks spanning his career and reintroducing his catalog to streaming-era listeners discovering golden-age soul for the first time.

Health challenges shadowed the final years. Carlton suffered a stroke in 2019, temporarily sidelining him from the touring that had sustained his career through decades of industry indifference. His original master recordings were among those destroyed in the 2008 Universal Studios backlot fire, a loss that affected hundreds of artists but carried particular weight for someone whose catalog represented not merely commercial product but documented evidence of a journey from Detroit child prodigy to certified hitmaker to resilient survivor. He recovered sufficiently to continue performing, though at a reduced pace that reflected both the limitations of his body and the realities of an industry that had long since moved on from the sounds he helped define.

What remains is a legacy with a career built on two undeniable smashes separated by seven years and surrounded by decades of work that deserved more attention than it received. Carl Carlton belonged to a generation of Motor City vocalists who absorbed Motown’s lessons without limiting themselves to Motown’s formula, artists who understood that Detroit’s musical education prepared them for journeys that might lead anywhere—Houston, Los Angeles, gospel sanctuaries, funk palaces, PBS specials, independent releases distributed through channels that bore no resemblance to the industry that first signed their contracts. His voice carried the particular warmth of Detroit soul, a tone shaped by church choirs and street corners and the peculiar energy of a city that made music the way other towns made automobiles: with precision, with pride, with an understanding that the product would outlast the factory.

The neighbor who leaned out that window in 1964 and demanded the radio be turned off heard something that would take six decades to manifest fully. This voice would soundtrack weddings and cookouts and late-night drives and reunion tours and compilation albums and film scenes and moments of private nostalgia for anyone who lived through the years when “Everlasting Love” and “She’s a Bad Mama Jama” defined the sound of American rhythm and blues. Carl Carlton understood, perhaps better than most, that a song could mean different things at different moments—that “everlasting” was both a promise and a burden, that a “bad mama jama” was both celebration and complicated desire—and he sang accordingly, never reducing his material to simple statements when layered interpretation was available. He leaves behind a catalog that rewards attention, a legacy that shaped the golden age of R&B, and a silence in which that remarkable voice once filled vacant lots, recording studios, and concert stages across five decades of American music.