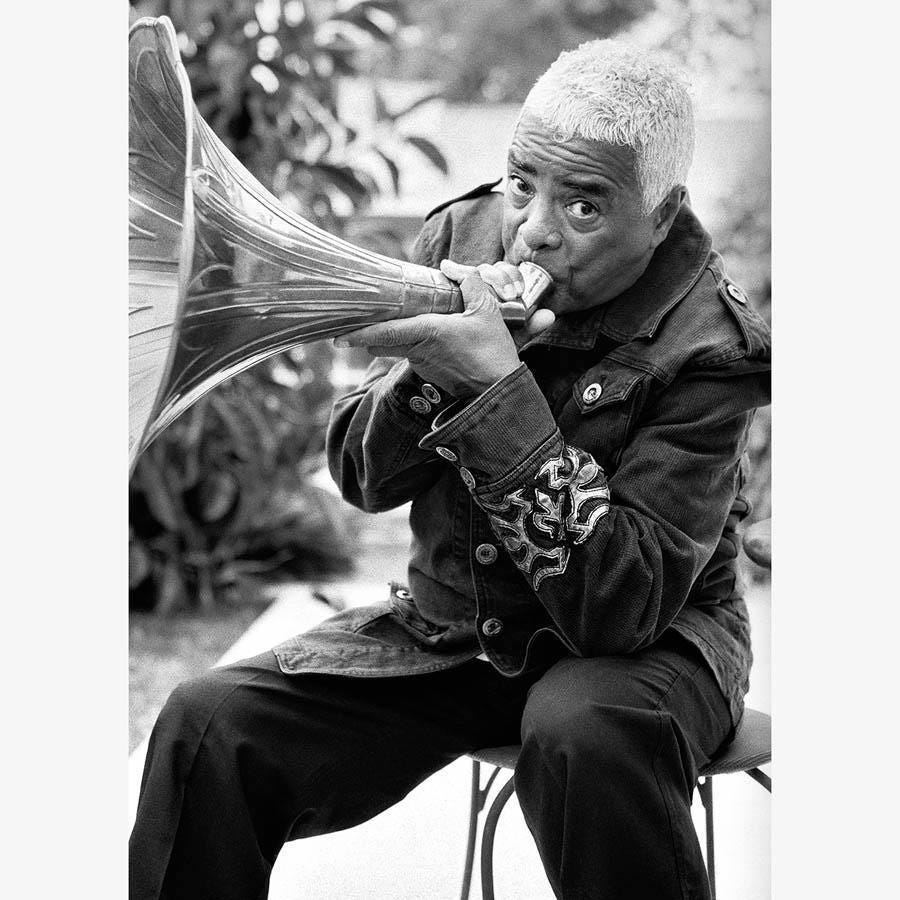

Our Tribute to Phil Upchurch (1941-2025)

A guitarist whose touch shaped generations of soul, jazz, R&B, and pop, Phil Upchurch left an imprint that stretches across some of the most enduring recordings of the last sixty years.

Phil Upchurch’s story ends where so many of his most famous sessions began: in a studio in Los Angeles, a city that became a second home to a Chicago kid who learned his craft on the bandstands of the South Side. He died there on November 23, 2025, at the age of eighty‑four, his wife Sonya Maddox‑Upchurch quietly confirming the news without giving a cause or even specifying where in the city it happened. This is another devastating loss for Black music, not because he was a household name, but because his guitar appears on so many records that people love without realizing the common thread. Upchurch was never a star in the conventional sense; he was the glue in sessions whose songs became fixtures of American life. It is impossible to recount his career without acknowledging that the joy and groove in Chaka Khan’s 1978 anthem “I’m Every Woman,” the taut drive of Michael Jackson’s “Workin’ Day and Night” from Off the Wall, and the warmth that wraps Donny Hathaway’s perennial holiday hit “This Christmas” all bear his touch. He played the same instrumental on two landmark versions of Bobby Womack’s “Breezin’,” first for Gábor Szabó in 1971 and again on George Benson’s 1976 rendition, which pushed the album Breezin’ to the top of the Billboard 200. Those credits merely hint at the breadth of a career that spanned more than six decades and touched more than a thousand recordings.

Upchurch’s life began far from Los Angeles, in Chicago, on July 19, 1941, where his father, a jazz pianist, raised him in a house full of rhythm. He received a ukulele when he was thirteen, a gift that opened a path to guitar, bass, and drums. Soon, he was playing professionally; friends from high school recall that by sixteen, he was already gigging around town. Jazz was his first love, and he studied the records of Oscar Peterson and Jimmy Smith; the latter’s albums became his “bibles.” After graduating, he took a job as a guitarist with the Spaniels, a vocal group known for “Goodnite, Sweetheart, Goodnite,” and toured the Midwest. This early exposure to R&B and doo‑wop shaped his versatility; Upchurch learned to support singers without overpowering them, a skill that would define his future sessions.

Success as a solo artist came quickly. In 1961, he recorded “You Can’t Sit Down,” an instrumental single that wed gospel drive to funky guitar riffs. Released under the name the Philip Upchurch Combo, the record sold more than a million copies and became a surprise hit; the Dovells later turned it into a vocal version that reached No. 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. Upchurch’s original track hit No. 29 and earned a gold disc. The song’s groove made it a dance floor staple and proved that an instrumental could crossover to the pop charts in an era dominated by vocal groups. Rather than chasing fame as a bandleader, Upchurch took the hit as license to follow his curiosity wherever it led.

One of the more surprising detours was his appearance on Cassius Clay’s 1963 spoken‑word album I Am the Greatest!, a proto‑rap record released when Clay was already a brash heavyweight contender but not yet Muhammad Ali. Upchurch’s guitar punctuated the boxer’s boasts, providing rhythmic commentary without calling attention to itself. Working on an album that blurred music and sports foreshadowed the genre‑blurring projects he would embrace later. Yet Upchurch’s path wasn’t without interruption. Drafted into the U.S. Army, he spent two years in Germany during the mid‑1960s as a radio reporter. Even in uniform, he found ways to make music; he performed in his unit’s glee club and jammed with other soldiers, sharpening his skills on borrowed instruments.

When he returned to Chicago, he entered what he later described as a golden period of learning. Chess Records hired him as a house guitarist, and he became a fixture at the company’s South Side studios. On any given day, he might cut a blues side for Muddy Waters, play a jazz groove for Ramsey Lewis, lay down a funky riff for Howlin’ Wolf, or back the Dells and Etta James. That environment demanded a chameleon’s touch; Upchurch could adapt his tone to the needs of a soulful ballad or a hard‑driving blues, and producers knew he would consistently deliver. He played bass as often as guitar, giving him insight into the rhythmic foundations of the songs he adorned. Working with Donny Hathaway in the early 1970s further stretched his imagination; together they developed a tight studio band that would shape Hathaway’s sound. Upchurch appears on all of Hathaway’s studio and live albums, including the 1972 classic Live, recorded at the Troubadour, where his improvisations on “The Ghetto” and “Voices Inside (Everything Is Everything)” elevated the material.

Upchurch’s ability to dissolve into any musical context made him indispensable in the 1970s. He joined Curtis Mayfield on the soundtracks for Superfly and Sparkle, films that defined the blaxploitation era with gritty social commentary and lush orchestrations. On Superfly, Upchurch’s guitar accentuated Mayfield’s falsetto pleas, while on Sparkle, he supported the big, horn‑driven arrangements that Aretha Franklin later made famous. He moved seamlessly from the Staple Singers’ gospel‑inflected soul to Minnie Riperton’s feather‑light ballads and from Natalie Cole’s pop‑soul hits to Bob Dylan’s mid‑1970s recordings. His rhythm work added muscle to Dr. John’s New Orleans funk and sophistication to Anita Baker’s early sessions. Each collaboration demanded a different vocabulary, yet Upchurch’s touch was always identifiable by its buoyant groove and clean articulation.

The session that introduced him to millions of radio listeners came in 1978 when he was asked to play on Chaka Khan’s “I’m Every Woman.” Written by Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson, the song required a guitar part that could cut through horns and background vocals without dominating the mix. Upchurch provided a rhythmic counterpoint, accentuating the backbeat with percussive strums and creating a lattice of notes that seemed to dance around Khan’s powerhouse vocals. The single spent three weeks at No. 1 on Billboard’s R&B chart and launched Khan’s solo career. A year later, he rejoined producer Quincy Jones on sessions for Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall. On “Workin’ Day and Night,” his guitar combined with Louis Johnson’s bass to create an irresistible funk pattern; Jackson’s youthful tenor rode the groove while Upchurch and Jones built layers of rhythm behind him. These hits, though credited to marquee artists, rely on his feel for timing and tone. Upchurch’s modesty kept his contributions in the shadows, but fellow musicians recognized his importance.

Holiday playlists around the world owe a debt to Upchurch thanks to his work on Donny Hathaway’s “This Christmas.” Recorded in 1970, the song has become a seasonal standard, and Upchurch’s relaxed strumming and subtle chord voicings give it a warmth that never grows old. He revisited the holiday spirit on Gábor Szabó’s “Breezin’,” an instrumental he recorded in 1971. Composed by Bobby Womack, the tune combines Latin‑tinged chords with jazz phrasing. Upchurch’s lines floated above Szabó’s acoustic guitar, hinting at the smooth jazz that would dominate radio later in the decade. When producer Tommy LiPuma asked him to play on George Benson’s version five years later, he refined the part, smoothing the edges and letting Benson’s fluid soloing take center stage. The 1976 recording became a pop and R&B smash, propelling the album to No. 1. Two sessions, five years apart, illustrate how Upchurch could reinvent a song without losing its essence.

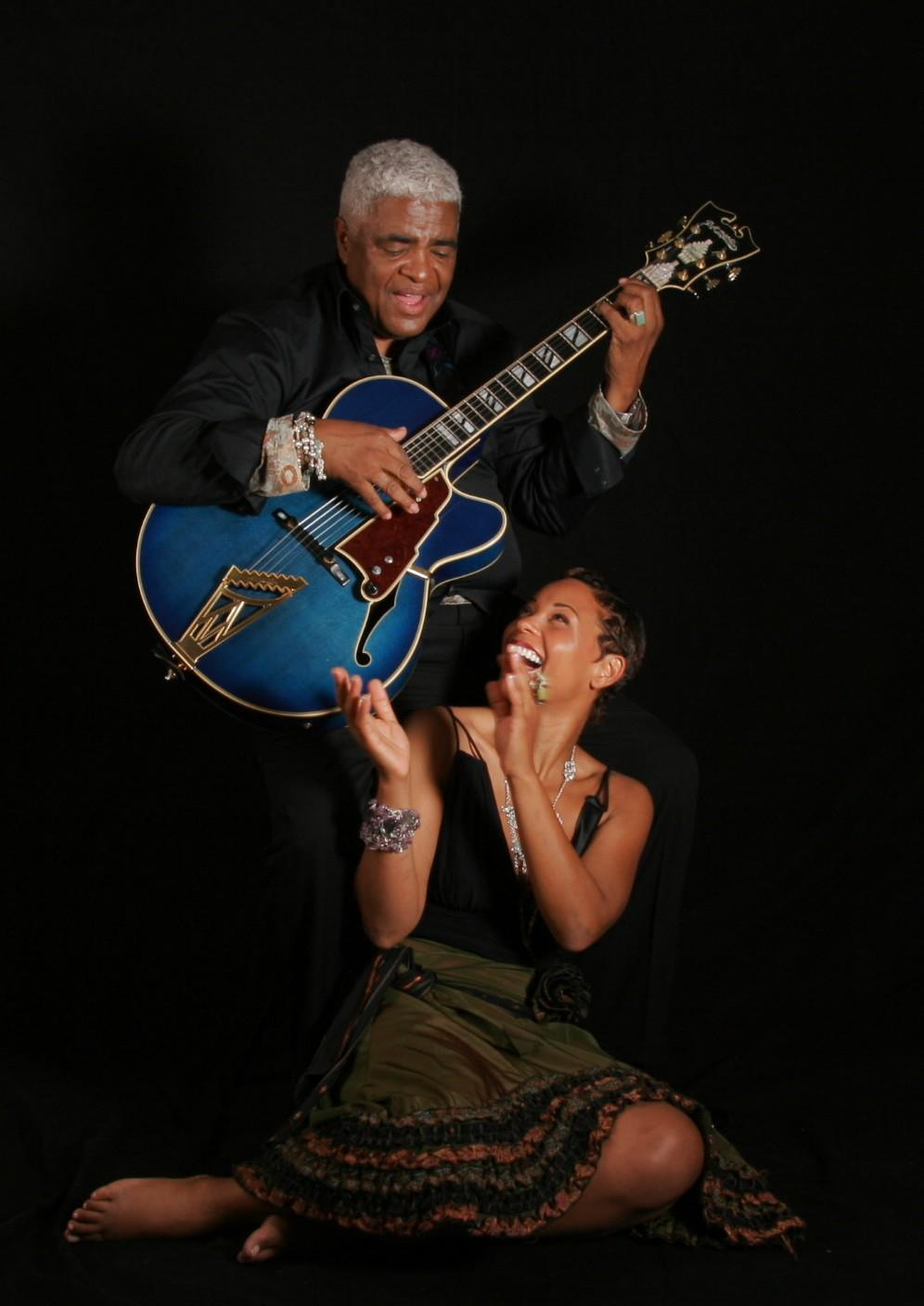

Despite his session work, Upchurch never stopped recording his own material. Throughout the 1970s, he released albums such as Darkness Darkness and Lovin’ Feeling, experimenting with rock, funk, and jazz fusion. He later collaborated with keyboardist Tennyson Stephens on Upchurch/Tennyson, merging their respective rhythmic sensibilities. In the 1980s and 1990s, he returned to his jazz roots, recording albums like Dolphin Dance and Midnite Blue and performing with organ giants Jimmy Smith and Jack McDuff. His teaching instinct led him to author instructional books; one of them, Twelve By Twelve, co‑written with his wife Sonya Maddox, offers a dozen blues guitar studies and reflects his desire to nurture younger players. At the time of his death, he was working on an autobiography, a project that would have chronicled an era of American music through the eyes of someone who played its grooves.

Upchurch’s adaptability was not simply a matter of technical facility. He had an innate sense of song, an ability to hear what a composition needed and how to serve it. Friends recall that he was as comfortable quoting Charlie Parker solos as he was laying down a two‑note vamp. He rarely took extended solos on pop records; instead, he focused on rhythmic motifs that supported the singer. His tone—warm, with a hint of grit—came from his touch rather than equipment. During sessions, he arrived early, tuned his instruments meticulously, and watched producers for cues. That professionalism earned him the respect of bandleaders like Quincy Jones and Curtis Mayfield, who often requested him by name. Jazz musicians admired his chordal vocabulary; funk and soul artists appreciated his groove. In every context, he listened first, then played.

Over the decades, Upchurch recorded nearly thirty solo albums and appeared on an estimated 1,000 records. The list of artists he worked with reads like a cross‑section of postwar American music: he backed gospel giants the Staple Singers, pop‑soul diva Natalie Cole, the ethereal Minnie Riperton, singer‑songwriter Bob Dylan, jazz‑rock saxophonist David Sanborn, New Orleans icon Dr. John, and R&B vocalist Anita Baker. He also composed material for other artists, including George Benson’s single “Six to Four.” His contributions extended into film and television scores and commercial jingles; like many session musicians, he sometimes worked without credit, leaving fans to discover his playing through careful listening. Yet he never complained about anonymity. In interviews, he insisted that the joy of making music with talented people outweighed any desire for fame.

Outside of music, Upchurch found creative outlets in photography and painting. He often brought cameras to recording sessions, documenting the camaraderie of musicians between takes. He exhibited his photographs in small galleries and on his website. His 2006 marriage to actress and singer Sonya Maddox led to further collaboration; they co‑wrote songs and stories, and she managed his career in later years. Those close to the couple describe their relationship as a partnership built on mutual respect and shared curiosity. Sonya accompanied him on tour, assisted with his instructional projects, and shielded him from the more exploitative aspects of the music business.

Phil Upchurch leaves no children, but his musical descendants are everywhere. Guitarists across genres study his voicings and rhythms; they sample his work in hip‑hop tracks and cite him as an influence in liner notes. The fluidity he brought to the instrument helped bridge jazz, soul, funk, and pop at a time when marketers policed those categories. Upchurch’s legacy is not in fame or chart positions but in the feeling his playing continues to evoke. He was, and remains, one of the most sought‑after session musicians of his era, a quiet architect of modern American music whose work will continue to be felt wherever people dance, celebrate, or reflect on the stories songs tell.