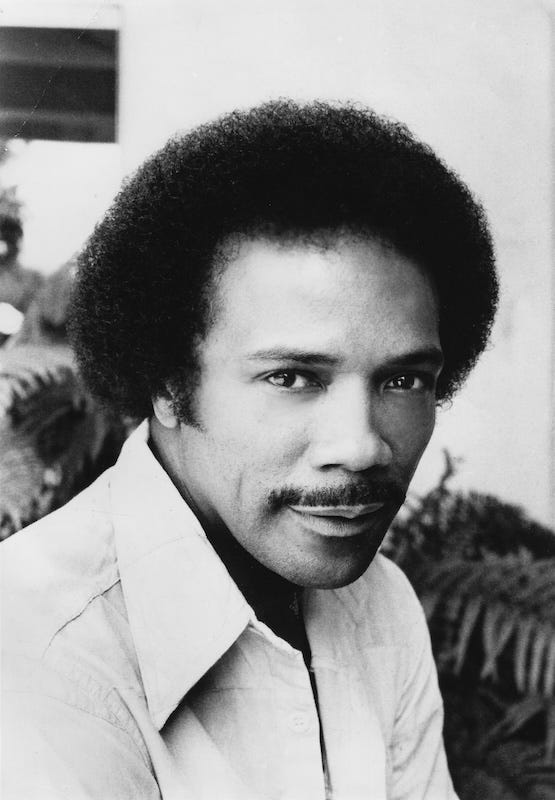

Our Tribute to Quincy Jones (1933-2024)

As Quincy Jones passes at 91, the music community reflects on his unparalleled contributions to the industry. His life's work attests to the power of music to heal, inspire, and unite.

When it comes to looking back at the trajectory of Quincy Jones, each of us feels dizzy, as the man Frank Sinatra nicknamed “Q” has left his mark on the history of popular music since the early 1950s. No list of names, even the most obvious of them, would be enough to do justice to the work and the work of a major creator who knew throughout his career how to make the talent of those with whom he collaborated shine.

Born on March 14, 1933, in Chicago’s South Side, Quincy Delight Jones Jr. had a difficult childhood due to his mother’s severe mental health problems and his parents’ separation. He was 10 years old when his family moved to Bremerton, Washington, then to Seattle. It was there that he met when he was only 14 a precocious young pianist of 16, Ray Charles Robinson, who was already performing in local clubs. A friendly and artistic relationship was formed that would last until the latter’s death. Music already occupied a major place in Jones’ life, under the influence of his mother, who sang regularly, and a pianist neighbor who allowed him to practice on his instrument. It was the trumpet, however, that seduced Jones.

At the age of 17, he received a scholarship to study music at the University of Boston, which led him to the Berklee School of Music, where he performed in local clubs but was interrupted when Lionel Hampton asked him to join his orchestra, both as a musician and arranger. It was in this context that Jones made his recording debut on May 21, 1951, with Hampton’s orchestra as trumpeter and arranger on the two parts of Eli, Eli, released on 78 rpm by MGM. His reputation quickly spread: that same year, Capitol called on him to conduct the orchestra on a few sides of Peggy Lee before many orchestras solicited him for his arrangements.

In 1953, he toured Europe for the first time with the Hampton Orchestra. The stay was an opportunity to make his recording debut under his name during Swedish sessions with Swedish-American All Stars of Circumstance, mixing some colleagues from the Hampton Orchestra and local musicians. It was also an opportunity for Jones to become politically and socially aware of the place of racism and segregation in his home country. This subject would govern his many engagements in the following years. During this period, he worked as a writer, arranger, and conductor for many sessions: in addition to Hampton, Clifford Brown, James Moody, Helen Merrill, Dinah Washington, Cannonball Adderley, and Clark Terry, among others, called upon his talents. From this time on, the world of R&B was not foreign to him, and he worked for Brook Benton, the Treniers, Big Maybelle, or Chuck Willis, then reunited with his old friend Ray Charles.

Based in New York, he worked from 1956 as a member of the orchestra of the CBS show Stage Show hosted by the Dorsey brothers, which gave him the opportunity to accompany the first nationally televised steps of Elvis Presley. He also joined the ranks of the Dizzy Gillespie ensemble, with whom he toured, under the aegis of the American government, in South America and the Middle East and recorded. Signed by ABC-Paramount, he released his first American albums there in 1957 but decided to settle in Paris, where he took lessons from Nadia Boulanger and Olivier Messiaen, an experience to which he was very attached and which he later willingly mentioned to justify his musical skills—the author of these lines remembers his cold anger during a public meeting at the North Sea Jazz Festival when a spectator thought it relevant to mention that the role of a producer essentially consisted of having a good address book. He worked at the same time for Eddie Barclay, writing and arranging for his big orchestra, but also for some of the artists on his label, such as Henri Salvador, in collaboration with Boris Vian.

While continuing to write regularly for American jazz stars, from Count Basie to Sarah Vaughan, he participated in the adventure of the innovative French vocal group the Double Six. At the same time, he formed his own big band, with which he toured throughout Europe. The result was an artistic success (the recording of one of these concerts at the Olympia was published a few years ago by Frémeaux), but a commercial failure. Almost ruined, Jones—who passed on the arrangements written for his ensemble to Ray Charles, who would make good use of them—decided to return to the United States and accepted the offer from Mercury, of which he became musical director and then, a few months later, vice-president, an exceptional role at the time for an African-American.

While he continued to work occasionally for others, notably for Impulse!, during Ray Charles’ legendary Genius + Soul = Jazz, Mercury allowed him to deploy the range of his talents broadly. In addition to his personal albums, including Big Band Bossa Nova in 1962, which included the ineffable Soul Bossa Nova, he contributed to the recordings of the label’s main stars (Billy Eckstine, Dinah Washington, etc.). He made his pop debut with the hits of singer Lesley Gore, who reached the top of the charts with It’s My Party in 1963. Determined to prove his versatility, he also produced the first international album of a young Greek singer, Nana Mouskouri. He also began a long-term collaboration with Frank Sinatra, which largely contributed to his notoriety with the general public, the crooner taking care to put him in the spotlight. In 1964, he published his first film score for The Pawnbroker by Sidney Lumet, the start of an activity in which he proved particularly prolific, for example, signing at least five original soundtracks in 1968.

Hyperactive, he chained together, in addition to his own records (Body Heat in 1974, the biggest success of his career), collaborations with artists and labels, passing his difficulty from Tony Bennett to Billy Preston, from Sinatra to BB King, the time to launch with the latter an improbable dance, The BB Jones! He put his growing notoriety to the service of his commitment to civil rights alongside Martin Luther King and then Jesse Jackson: he was thus one of the participants in the 1972 Expo organized by the latter and documented by the film Save the Children, recently made available by Netflix.

This incredible workload ended up weighing on his health, and he was forced to take a step back from 1974. This did not prevent him from launching his own production company, Qwest, the following year, under whose aegis he produced his own albums, notably The Dude, considerable success in 1981, and those of others, among which were obviously the three products of his collaboration with Michael Jackson (Off the Wall, Thriller and Bad), which helped to redefine what pop music was, but also spectacularly successful records for George Benson, Frank Sinatra, James Ingram, and Patti Austin. His primary role in the marathon session that gave birth to We Are the World helped to consolidate his central role in the music industry. However, he did not wholly neglect R&B, for example, accompanying the emergence of the Brothers Johnson for a few very successful albums.

An entrepreneur as much as an artist, he launched his label, Qwest, in 1980 and a few years later got involved in the production of films and television series, enjoying major success with The Color Purple—no less than eleven Oscar nominations—then in another register with The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. In 1993, he launched Vibe magazine, dedicated to African-American music and culture. In 2017, he was also associated with the launch of the online music video platform Qwest TV. In 1991, he organized a Miles Davis concert event in Montreux just a few weeks before the latter’s death. Less prolific than before, he nevertheless released a few personal records, Back On the Block in 1989 and Q’s Jook Joint in 1995, on which he enjoyed bringing together musical generations. While he continued to sponsor young musicians like Nikki Yanovsky or pianist Alfredo Rodriguez (as well as French singer Zaz), he was much less active musically from the 1990s onwards, which did not prevent him from making some special appearances on stage, including a tour that stopped at Bercy in 2019 and various anniversary celebrations, surrounded by friends, in Montreux. A final album in 2010, Q: Soul Bossa Nostra, saw him revisit some of the most extraordinary pages of his career with guests.

In 2001, he published his memoirs, Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones, and a documentary that does not hide his personal flaws; Quincy, co-directed by one of his daughters, was dedicated to him in 2018. Having become an iconic figure, accumulating titles and honors, he appeared in his own role in the film Fantasia 2000 as well as in the second volume of the Adventures of Austin Power. His stature is such that he only needs to make a brief appearance on stage to trigger the emotion of the audience, as the author of these lines will note one evening at the North Sea Jazz Festival when the great man will come in person to provide the introduction to Alfredo Rodriguez’s concert in a small room.

It is obviously impossible to summarize such a journey in a few discographic references, especially since the most ambitious anthologies (among countless products from the public domain), but he left behind decades worth of greatness.