Our Tribute to Sly Stone (1943-2025)

Sylvester Stewart exits, but Sly Stone remains, encoded in the DNA of any musician who believes rhythm and fellowship belong in the same sentence.

Sylvester Stewart, who’s known to the world as Sly Stone, entered the world on March 15, 1943, and left us this morning, June 9, 2025, after a long fight with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was eighty-two. News of his passing spread with the same speed that once carried “Dance to the Music” across transistor radios, touching generations who learned to count the down-beat through his example. The grief feels personal because Stone’s records never stood at arm’s length; they invited listeners inside a utopian rehearsal for the country they hoped to inhabit. Today, that invitation sounds both fragile and durable—fragile because its creator is gone, durable because the grooves still pulse with the stubborn belief that rhythm can do what politics struggles to finish.

Stone’s optimism, like his rhythm sense, was cultivated early. His parents, K.C. and Alpha Stewart, led a Pentecostal congregation in Vallejo, California, where all five Stewart children learned harmony from hymns and discipline from Sunday schedules. Sylvester became a local prodigy, mastering guitar, bass, keyboards, and drums before most classmates finished driver’s ed. At fifteen, he cut doo-wop singles with the Viscaynes, one of the region’s few interracial vocal groups, foreshadowing the boundary crossing that would define his future. On air at KDIA under the name “Sly Stone,” he mixed Beatles singles with gospel exhortations, quietly turning the Bay Area’s most popular soul program into an informal seminar on genre fluidity. Long nights as an engineer at Autumn Records followed, where he produced early hits for the Beau Brummels and Bobby Freeman while cataloging studio tricks that would later make “Riot” hum and hiss like a restless conscience.

By late 1966, Stone wanted a band equal to his imagination, so he merged his brother Freddie’s outfit with a loose studio crew. The result was Sly and the Family Stone, which looked like the integrated classroom of a civil rights textbook and sounded like Little Richard sitting in with the James Brown horn section at a Haight-Ashbury jam. Cynthia Robinson’s trumpet cut through the fuzz guitar, Larry Graham’s newly minted slap-bass style forced drummers everywhere to recalibrate pocket depth, and everyone took turns at the microphone. This on-stage democracy wasn’t gimmickry; it was the message. Instead of sermonizing about togetherness, the Family demonstrated it in real time, a living argument that soul, rock, and psychedelia were chapters of the same American volume.

“Dance to the Music” hit national radio in early 1968 and functioned as a bright-colored calling card. Each instrumental voice introduced itself—“Cynthia On the horn!”—as if inclusion were a celebration, not a footnote. “Everyday People” arrived months later and crystallized the philosophy in three minutes: prejudice dissolves when you share a chorus. Both singles stormed the charts, but their greater achievement was cultural. By centering a mixed-gender, interracial collective, Stone rewrote what mainstream success could look like in a decade when news broadcasts still showed cities on fire. The hits kept coming—“Hot Fun in the Summertime,” “Stand!,” “I Want to Take You Higher”—while the band’s stagecraft made every festival date feel less like a concert and more like a community picnic punctuated by feedback solos.

That communal spirit reached apotheosis at Woodstock in the predawn hours of August 17, 1969. Scheduled after a string of weather delays, the Family Stone walked onstage at 3 a.m. to a mud-soaked field of half-sleeping idealists and proceeded to jolt them awake with a call-and-response that echoed well past sunrise. Stone’s refrain of “higher” sounded literal and spiritual at once, uniting spectators in a rhythmic mantra that cameras preserved for the festival film, ensuring future audiences could feel the voltage. The set helped erase whatever thin line remained between funk and rock, showing that syncopation and distorted guitars could coexist without ceding an inch of power.

Success carries its own gravity, and by the dawn of the new decade, Stone treated that gravity as subject matter. There’s a Riot Goin’ On (1971) swapped Technicolor horn passages for molasses-slow drum loops, vocals that drifted like late-night monologues, and lyrics shaded by cynicism born of assassinations, broken political promises, and personal burnout. The record bewildered executives hunting a fresh summer anthem, yet it forecast entire futures: the relaxed swing of G-funk, the collage aesthetic of indie neo-soul, even the lo-fi filters embraced by bedroom producers half a century later. “Family Affair,” its weary hit single, captured domestic love and tension with a frankness R&B had seldom risked.

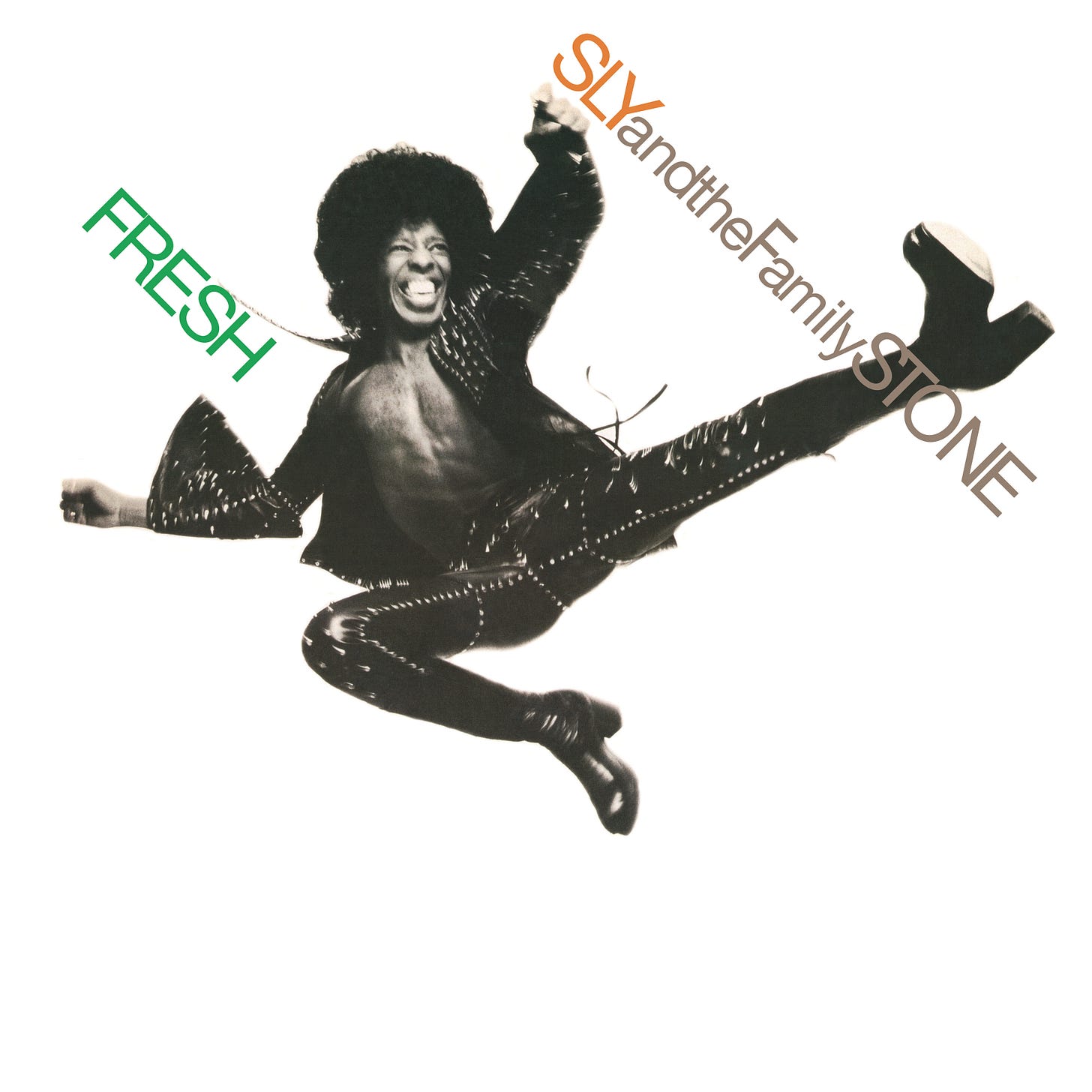

Stone’s restlessness resurfaced on Fresh (1973). Here, Graham’s bass and Andy Newmark’s drums stitched tight lattices that rappers would mine when the sampler replaced the rhythm section. Stone’s own vocal phrasing—gliding between croon and spoken commentary—anticipated the half-sung cadences of modern hip-hop. Yet commercial victories failed to quiet private storms. Drug use escalated, band camaraderie frayed, and managers struggled to coax Stone onto airplanes, let alone onto stages. By the mid-1970s, the original Family Stone splintered, and its architect began a long, erratic retreat punctuated by under-promoted solo releases, cameo appearances on projects by George Clinton and Jesse Johnson, and fleeting concert cameos that felt more cautionary than triumphant.

While Stone vanished from marquees, he remained omnipresent in the record collections of future architects. Prince borrowed the ethic of playing nearly every instrument on a track; Michael Jackson lifted rhythmic accents; Public Enemy looped “Sing a Simple Song” like a warning siren; D’Angelo treated “In Time” as a harmonic blueprint. Each homage testified to Stone’s unnoticed longevity: even absent from public view, he shaped the vocabulary of Black pop, and by extension, global pop. Sampling law inadvertently extended his influence—every clearance request forced younger producers to study master tapes, turning legal paperwork into musicology.

Recognition eventually reached the man himself. The 1993 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony brought Stone onstage for what became the shortest speech in induction history—he whispered, “See you soon,” then disappeared—but it reminded viewers that the myth was flesh and blood. A 2006 Grammy tribute drew him out again, blond mohawk peeking beneath a tall hat, just long enough to lead “I Want to Take You Higher” before vanishing into the wings. Two years of homelessness followed, painfully documented in court depositions during a royalties lawsuit he later won. Yet resilience surfaced once more with the 2023 memoir Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin), a plain-spoken chronicle that balanced regret with flashes of mischievous wit and emphasized hard-earned sobriety.

Stone spent his final months surrounded by family, tinkering with keyboards between medical appointments, curious about new plugins young relatives installed on a laptop by his bed. Visitors describe him pausing mid-chord to recount stories—how Cynthia Robinson’s trumpet line on “Stand!” emerged in one spontaneous take, or how he once disguised himself in a trench coat to watch a nonexistent “Sly Stone impersonator” play Oakland so he could gauge whether the myth outweighed the man. If time dulled his singing voice, it never touched the sense of wonder that music might still save dinner-table arguments, if only someone pressed play at the right moment.

Now the turntables spin without him. Yet each slap-bass flourish in a bedroom beat, every festival bill that treats racial and gender parity as baseline, and every choir of strangers shouting “higher” at a club night where “Thank You” drops near closing time, confirms that Stone’s central hypothesis endures: everyday people, given the right groove, can form a better union. As fans mourn, the records keep offering instructions—sing together, move together, stay together. In that sense, the curtain never falls. Sylvester Stewart exits, but Sly Stone remains, encoded in the DNA of any musician who believes rhythm and fellowship belong in the same sentence.

We will miss you, Sly Stone. Watch the Sly Lives! (Aka the Burden of Black Genius) Documentary, if you haven’t.

beautiful write up! Sly lives! <3

Together with Bob Dylan he turned me into a „Real Music“ Lover.

I saw the Woodstock Movie 1975 in the local Cinema and he changed my whole Outlook on Music.

2007 I saw him in Montreux!

One of the greatest Innovators in Music, with his profound Influence on Prince has left us.