Ranking Discographies: Solange

From a forgotten teen-pop debut to a Grammy-winning meditation on Black womanhood, Solange’s catalog tells the story of an artist figuring it out in public. We’re ranking her discography.

Solange Knowles married her high school sweetheart at seventeen, had a son at eighteen, and got divorced before she could legally drink. She spent her early twenties bouncing between Houston, L.A., and Brooklyn while her older sister became the most scrutinized woman in popular music. By the time she settled in New Orleans and started recording in rural Louisiana, she’d already released three albums that nobody outside of R&B circles remembered. The fourth one changed that. She became the Knowles who made art-world darlings swoon, the one Pitchfork championed, the one who turned a TIDAL exclusive into a cultural talking point. Her catalog is thin—five projects total—but the distance between the first and last is enormous.

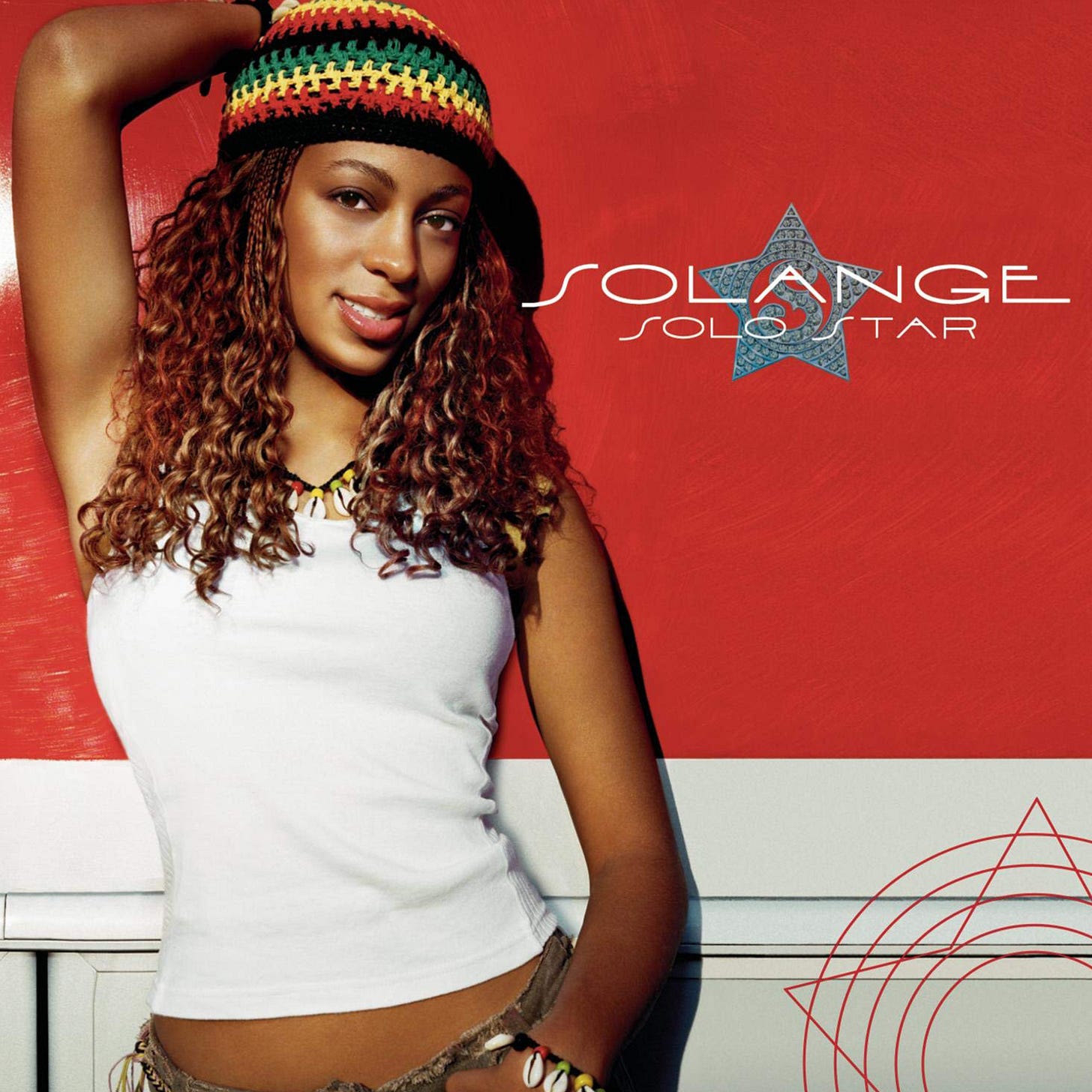

5. Solo Star (2003)

Music World Entertainment pushed this as a vehicle for the other Knowles daughter, and the label’s fingerprints are everywhere. “Crush,” produced by The Neptunes, has the brittle claps and synth stabs that Chad Hugo was putting on everything in 2003, but Solange sounds tentative against it, like she’s waiting for permission to take up space. The Missy Elliott-penned “Dance with You” borrows Missy’s hiccupping cadences without any of the personality that made those tics work. Most of the album defaults to mid-tempo R&B balladry that hits every mark of the era—the breathy verses, the key change on the final chorus, the obligatory spoken-word breakdown—without landing a single memorable hook. “Feelin’ You (Part II)” got a video, charted modestly, and vanished. The whole record feels like an assignment completed on time but without enthusiasm. She could clearly sing; she just didn’t have anything to say yet.

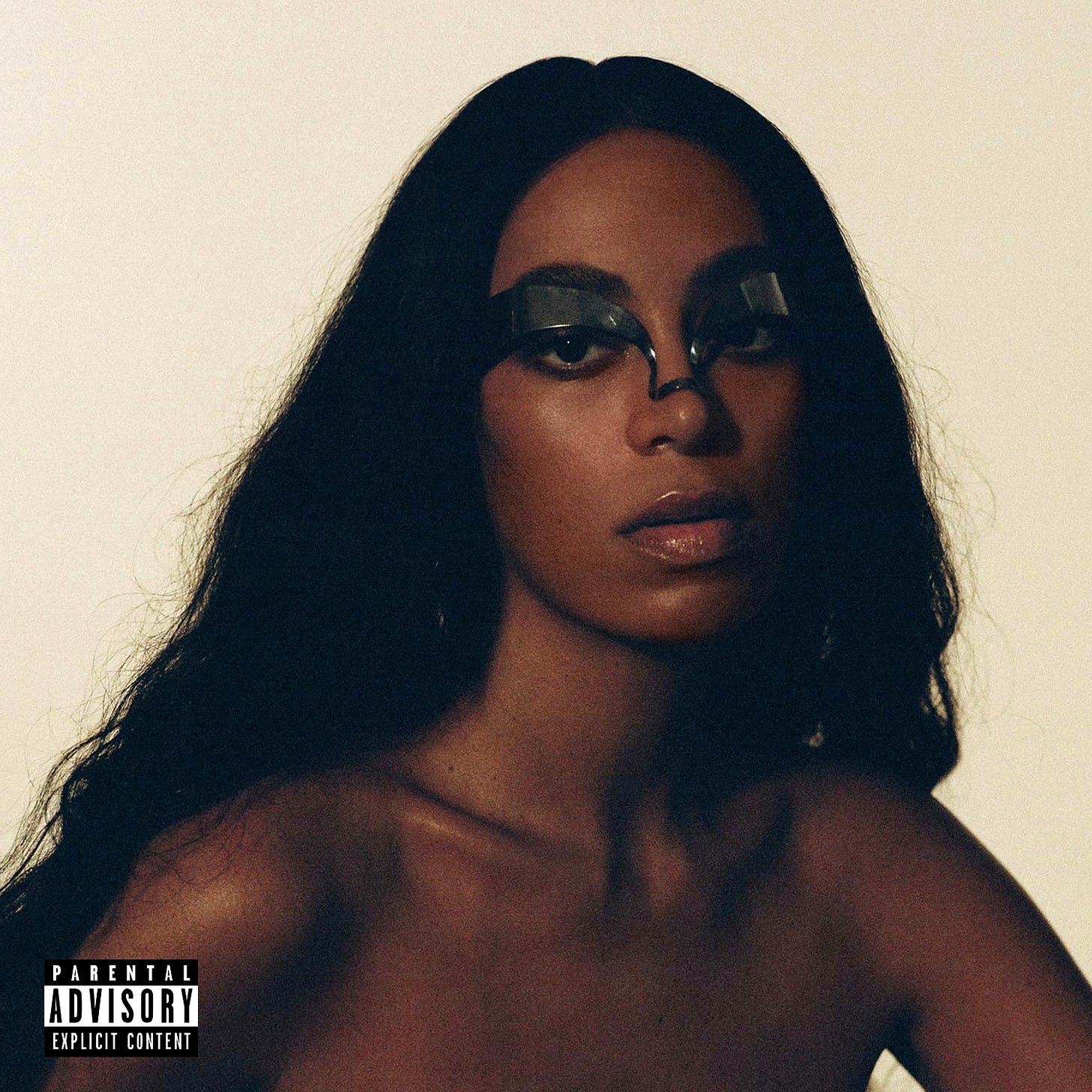

4. When I Get Home (2019)

A love letter to Houston that requires you to already love Houston. The runtime says thirty-nine minutes, but the actual songs are buried under interludes, ambient drones, and spoken-word passages that sometimes work (the Debbie Cameron sample on “Dreams”) and sometimes feel like filler dressed up as intention. Playboi Carti shows up on “Almeda” and does exactly what you’d expect: sparse ad-libs, a hook he barely commits to, gone before the three-minute mark. Gucci Mane and Scarface appear as local totems more than collaborators. The album’s most successful stretch is “Sound of Rain” into “Almeda,” where the chopped-and-screwed aesthetic actually pays off and the vocal loops accrue weight through repetition. The title track, split across four interludes, never coheres into a full idea. “My Skin My Logo” with Tyler, The Creator and Pharrell has three of the most charismatic voices in contemporary music trading bars, and it still feels undercooked. The commitment to abstraction is admirable; the results are inconsistent. Some of this is genuinely hypnotic. Some of it is texture pretending to be substance.

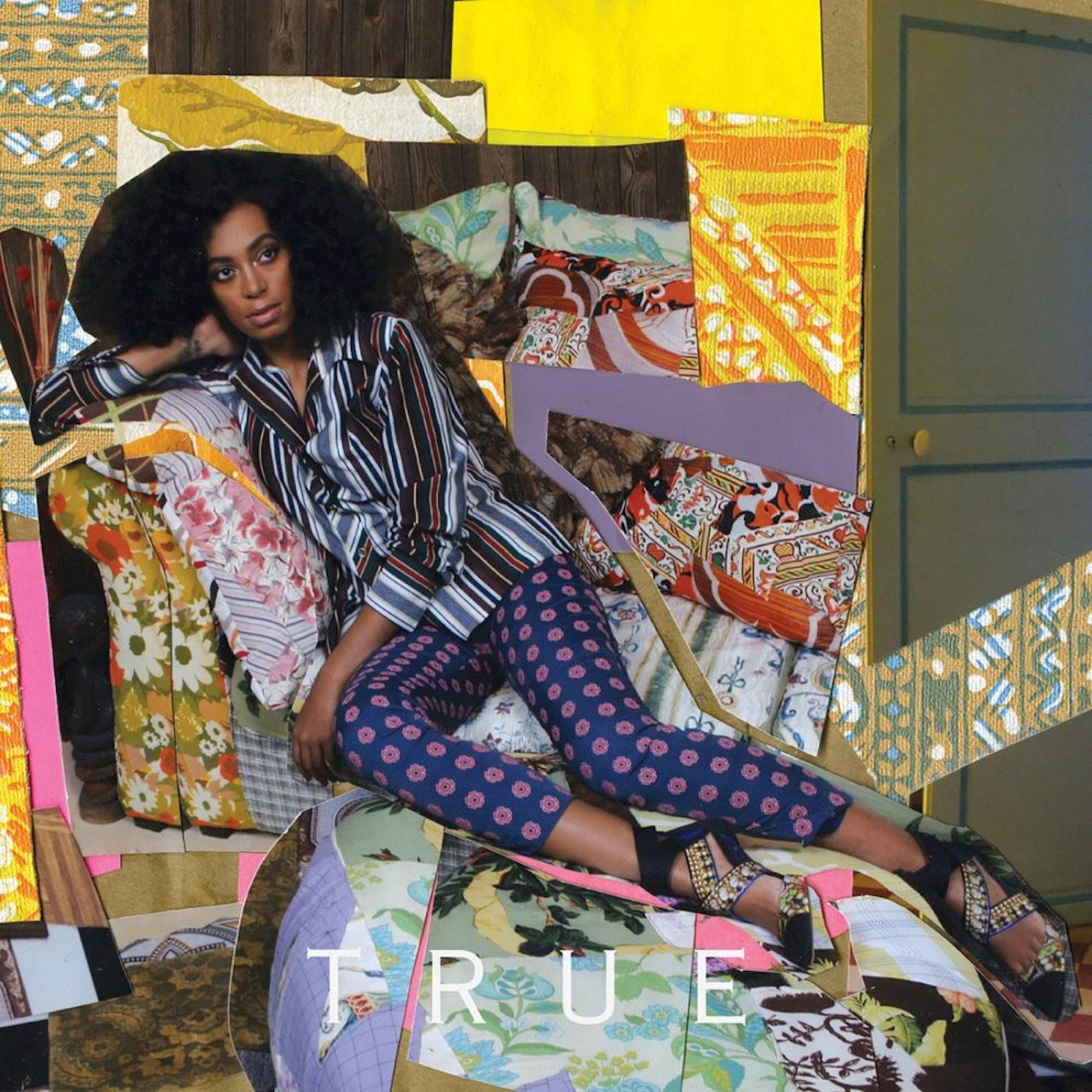

3. True EP (2012)

I bet you weren’t there for this one. The EP that signaled the turn. Solange linked with Blood Orange’s Dev Hynes for most of these seven songs, and his influence—new wave synths, post-punk drum patterns, melodies that favor repetition over resolution—suited her voice better than anything she’d recorded before. “Losing You” became the obvious single after the Melina Matsoukas-directed video (shot in Cape Town) went viral on music blogs. The song’s hook is simple (“I’m losing you”) repeated over cowbells and handclaps, but the simplicity is the point. “Locked in Closets” is murkier, weirder, a Hynes production that sounds like it could’ve landed on a Chairlift record. “Some Things Never Seem to Fucking Work” is the bluntest lyric she’d written to that point, a plainspoken accounting of romantic failure without any of the melismatic flourishes that R&B singers typically use to telegraph emotion. The whole EP runs thirty minutes and doesn’t waste a second. It sold modestly, but everyone who heard it started paying attention.

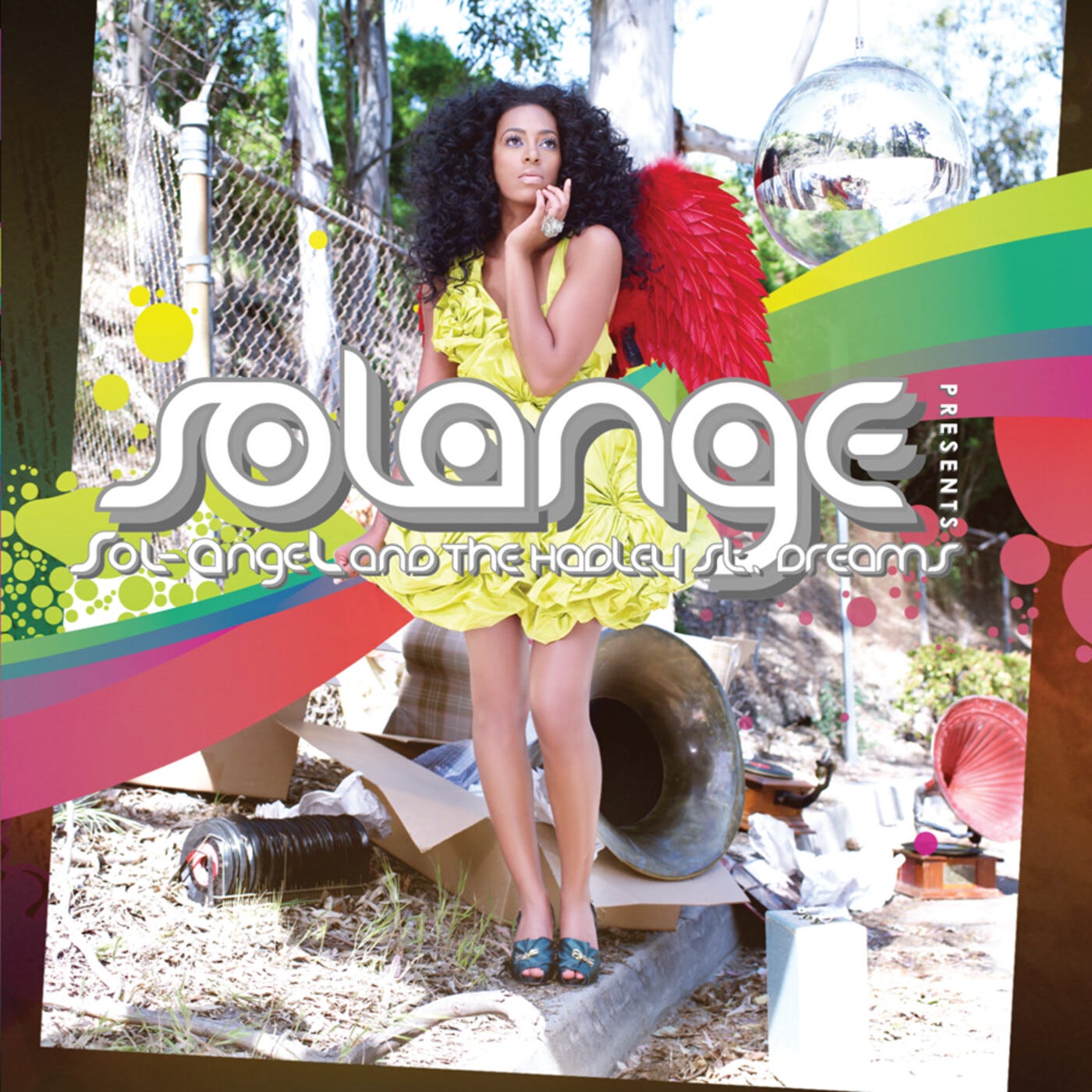

2. Sol-Angel and the Hadley St. Dreams (2008)

The record that proved she wasn’t a fluke and wasn’t chasing her sister’s lane. Solange moved to L.A., assembled a production team that included Cee-Lo Green, the Neptunes, and Mark Ronson, and made a retro-soul album that never stooped to pastiche. “I Decided” opens with a horn fanfare that could’ve come off a 1968 Motown single, but the groove underneath is slippery and syncopated in a way that keeps it from feeling like a museum piece. “T.O.N.Y.” personifies a luxury car as a lover—a gimmick that should be corny but works because she commits to the bit without winking. “Sandcastle Disco” has a bassline lifted from the Bee Gees’ “Love You Inside Out” and makes it work as a summer jam. The album’s best song might be “I Told You So,” a breakup track where she sounds genuinely wounded rather than performatively sad, her voice cracking on the bridge in a way that feels accidental and real. The established her as someone with taste and range. Without this album, nobody would’ve taken A Seat at the Table seriously.

1. A Seat at the Table (2016)

Speaking of, this is the album that turned Solange into a name that didn’t require a “Beyoncé’s sister” qualifier. She recorded most of it in New Iberia, Louisiana, a small town an hour west of New Orleans, and the isolation shows—this is a quiet, interior record even when the subject matter is explicitly political. “Cranes in the Sky” took nine years to finish; she first wrote it in 2008 and kept returning to it, tweaking the production and the lyrics, until it finally felt complete. The song’s central image—trying to drink away, sex away, work away the feeling—is simple enough, but her delivery sells it, the repetition of “away” becoming a kind of exhausted hymn. “Don’t Touch My Hair” pairs her with Sampha and makes a direct statement about Black bodily autonomy without ever sounding like a lecture. “Mad” brings Lil Wayne in for a verse about justified Black anger, and he delivers one of his most focused performances in years. The interludes—her mother and father discussing their experiences with racism, Master P talking about Black ownership—give the album a documentary quality without disrupting the flow. “F.U.B.U.” states its thesis in the title and the hook: “Some shit is just for us.” The whole record operates at a low simmer, never chasing a radio hit, never oversinging, trusting that it will lean in. It sold well, won a Grammy, and finally gave her an audience that matched her ambition.

You had to be there when "True" came out. I remember the video but most importantly she had her natural hair out! For the girls who were on the internet and who were just starting to also wear their hair out, it was huge! And it's true, that EP clearly said "I'm not just her sister, I'm different but I'm just as good." I listen to it so often, "Losing You" in particular reminds me of my first year living solo as a young adult.

I love When I Get Home. Its spaciness and looseness make it feel so free. Not a lot of lyrics on that album haha but a very great album to listen to and let your imagination run free. When words fail, the instrumentation and the vocals can take you where you need to go.