Retrospective Review: Nothing Was the Same by Drake

Drake has transformed from an improbable rapper to a recognized one.

Nothing Was the Same marked a discernible shift in musical direction compared to his prior work, notably the 2011 album Take Care. Before its debut, the Toronto-based rapper intimated that this project would deviate from its predecessor both stylistically and in tempo. True to his word, the album offered a blend of pensive introspection and exultant bravado, delivered over a medley of beats that were at once moody and celebratory. Produced by his frequent collaborator Noah “40” Shebib, among others, the project was meticulously crafted. Drake didn’t merely record; he curated each track, fostering an atmosphere inviting introspection while retaining a commercial appeal that few artists balance skillfully.

The recording process was a chapter characterized by a focused commitment to creating a transformative sonic experience. Holed up in studios spanning locations as varied as Toronto and Los Angeles, Drake emerged as not just a rapper or even a singer but a multi-faceted artist with a vision to meld genres. Not content to merely rap over beats, he pushed the envelope with unique samples, vocal distortions, and finely calibrated orchestration. This wasn’t mere music-making; it was an alchemy of sound, carefully orchestrated to create a multi-textural experience that evoked many emotions.

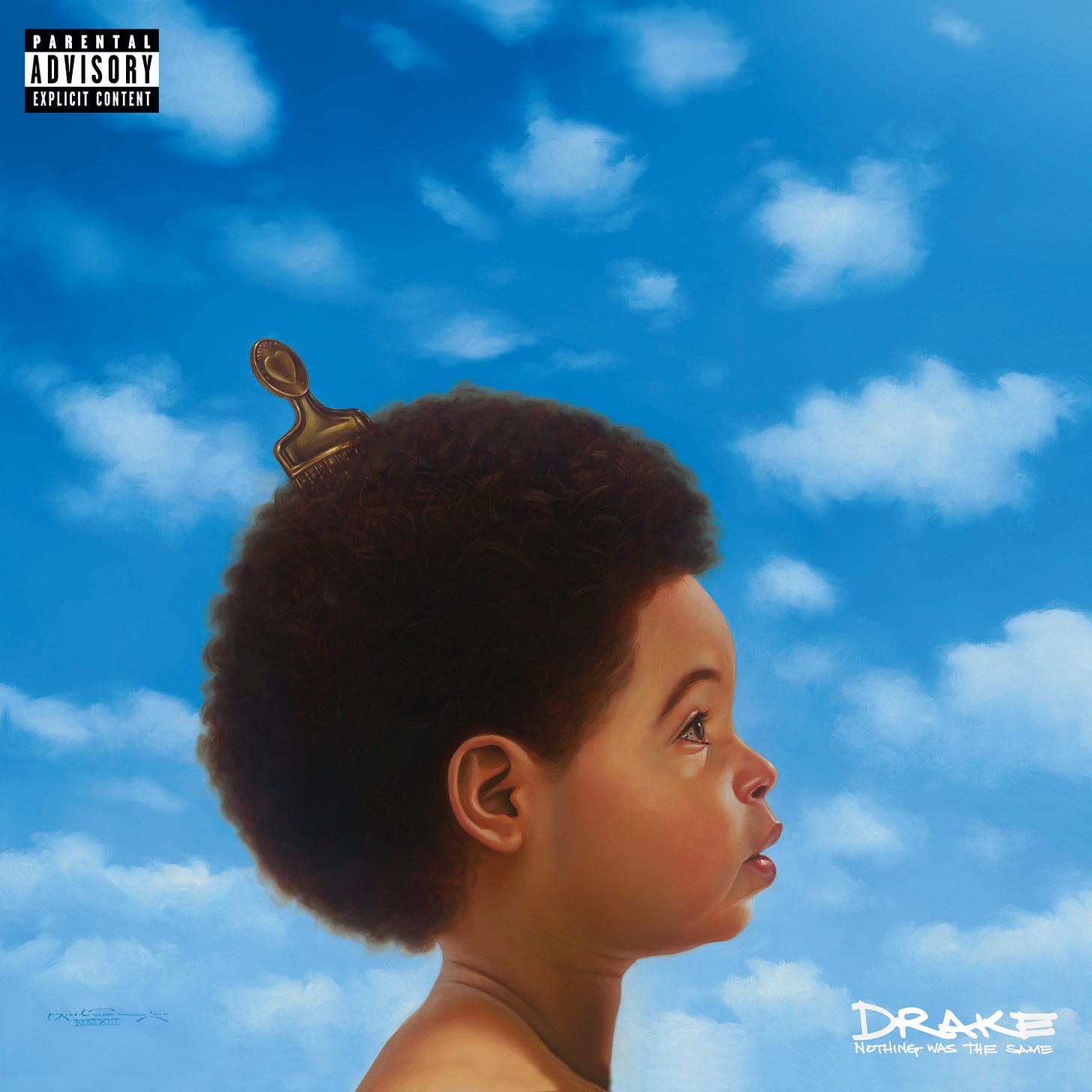

Equally notable was the album cover, a piece of visual art designed by acclaimed artist Kadir Nelson. Known for his portraits that often engage with African-American history and culture, Nelson presented two side-by-side profiles of Drake: one as the adult artist we know, the other as a younger version of himself. The duality served to magnify the thematic concerns of the album, explicitly the evolution of Drake both as an artist and as an individual. The artwork became an additional layer, another text for fans and critics to interpret and integrate into their understanding of the album.

The lead single from his third studio album, “Started From the Bottom,” resonated sonically and culturally. The lyrical brilliance of the song lies in its raw, unabashed autobiography, encapsulated in lines like, “Boys tell stories ‘bout the man / Say I never struggled, wasn’t hungry, yeah, I doubt it.” Here, Drake confronts his skeptics head-on, challenging preconceived narratives about his rise to fame while reinforcing his genuine rags-to-riches tale. Drake’s emotional outpour allows the audience to experience the peaks and valleys of his come-up, making it relatable to many who hear echoes of their aspirations in his words.

When it comes to the song’s production, helmed by Mike Zombie and Drake, the auditory architecture carries the same ethos of stark minimalism that matches the lyrics’ unembellished storytelling. The syncopated piano loops and restrained drum patterns create a canvas that lets Drake’s vocals fill in the nuances instead of overpowering them. The track’s influence has been multi-generational, permeating pop culture and fostering a vernacular of ambition repurposed in memes, parodied in sketches, and cited in countless interviews.

The song has had a lasting impact, not merely as a popular tune but as a cultural phenomenon that challenges our notions of success and the diverse routes to achieve it. While some may argue that the song simplifies the complexity of Drake’s path to stardom, its imprint on the modern cultural psyche is irrefutable.

Drake departs from his signature rap cadences to explore the malleability of his vocal range within an R&B framework with “Hold On, We’re Going On.” The verses, tinged with a sense of yearning, are a poetic discourse on love’s complexities. Drake’s voice is vulnerable yet determined, seamlessly floating over a melody that melds electro-funk elements with soft, pulsating synth lines. These compositional choices, guided by producers Majid Jordan, Nineteen85, and Noah “40” Shebib, evoke a timeless, almost nostalgic, atmosphere, rendering the track an instant classic upon its release.

The opening track, “Tuscan Leather,” is an unapologetic showcase of the rapper’s multifaceted talent, both in terms of lyrical ingenuity and nuanced production. The song begins with an ambitious flip of a Whitney Houston sample, “I Have Nothing,” manipulated to set a haunting, contemplative mood. Produced by Noah “40” Shebib, the sonic framework does a delicate dance with Drake’s flow, transforming its nearly six-minute length multiple times. The metamorphosis in production functions almost like different scenes in a play, with each act shedding light on another facet of Drake’s life and career.

Drake’s verses on the track offer a window into his psyche, reflecting fame, vulnerability, and ambition. He raps, “Yeah, Tom Ford Tuscan Leather smelling like a brick / Degenerates, but even Ellen love our sh*t.” These lines reveal the dualities Drake wrestles with: the luxury and excess represented by the Tom Ford cologne juxtaposed against his need for broad cultural acceptance, as evidenced by the mention of Ellen DeGeneres. Later, he spits, “Bench players talking like starters, I hate it.” The sentiment captures Drake’s frustration with the critiques and judgments he faces, not from fellow successful artists but those who have yet to earn their stripes in the rap game.

Yet, “Tuscan Leather” is not simply a vehicle for Drake’s musings. The song can be viewed as a sophisticated introspection into the artist’s struggle with success. Within its complex structure, the track accommodates his concerns about authenticity and the fickleness of public opinion. In the line “How much time is this ni**a spending on the intro?”, he acknowledges the risk he takes by dedicating so much time to a song that introduces the album. It’s a meta-commentary on his artistic choices, almost daring the listener to question him.

Where the song truly shines is in its marriage of form and content. The ever-changing musical backdrop, courtesy of Shebib’s artful production, dovetails seamlessly with Drake’s versatile flow and thematic shifts. As it navigates through the changing soundscapes of reversed samples and unexpected tempo adjustments, they’re also guided through the different corners of Drake’s inner world.

“Furthest Thing” emerges as a compelling duality of confession and celebration. The track navigates the nuanced territories of fame, loyalty, and emotional dissonance. In the opening lines, “Somewhere between psychotic and iconic / Somewhere between I want it and I got it,” Drake captures the paradox that defines his life. The contrast between yearning and attaining sketches complex emotional geography where satisfaction is elusive. This duality resonates even in the beat, with its laid-back piano melody and trap-influenced percussions serving as both backdrop and amplifier to Drake’s contemplations.

The song undergoes a transformative shift midway, almost like slicing its identity into fragments. The beat switches from a softer, pensive tone into a more rigid, synth-infused cadence, illustrating Drake’s transition from a state of reflection to assertiveness. The two musical segments could stand alone as independent tracks (the Jake One beat is fantastic), yet their juxtaposition adds depth to the song that a single continuous beat might not have achieved. In the same breath, Drake oscillates between vulnerability and hubris, casting each as sides of the same coin.

With “Wu-Tang Forever” it captures a dichotomy in modern rap culture. On one hand, it pays homage to the iconic rap collective Wu-Tang Clan through its sample of “It’s Yourz,” a track from the group’s seminal 1997 album. On the other, the song is not a replication of Wu-Tang’s raw, gritty approach but rather a distinct Drake offering, complete with introspective verses and smooth production. This dual essence is a classic example of how Drake maneuvers between the old and the new, exhibiting respect for hip-hop’s past while pushing its sonic parameters.

While his decision to sample Wu-Tang drew criticism for not living up to the rap collective’s hardcore reputation, it’s worth considering that Drake’s interpretation represents an evolution of the genre. He bridges two disparate worlds in rap, melding styles and eras. By sampling Wu-Tang’s music, he draws new listeners to explore the group’s influential work. Conversely, using a softer musical canvas allows Drake to impart his unique flair, solidifying his position as a transformative artist in rap music.

Produced by DJ Dahi, “Worst Behavior” detonates like an auditory firework, laced with defiant energy. The beat follows a minimalist approach, laying a foundation of distorted bass and synthetic handclaps that shatter any illusion of subtlety. The production is a purposeful paradox: its simplicity contrasts with Drake’s complex emotional landscape. It’s a stark backdrop that allows Drake’s lyrical assertiveness to remain in the spotlight.

In his verses, Drake flips through the pages of his life, juxtaposing his struggles with his current status. Take the line, “Remember? Muhf*cka? Remember?” His repetition of the word ‘remember’ doesn’t just invoke nostalgia; it confronts listeners with a ferocity that demands acknowledgment of his transformation. Another line, “Who’s hot, who not? Tell me who rock, who sell out in stores?” reflects Drake’s scrutiny of the fickleness of fame and his scrutinization within the industry while paying homage to Mase’s opening verse of “Mo’ Money, Mo’ Problems.” He asks, “Who has the cultural and commercial relevance to claim success truly?”

In “From Time,” the Canadian rapper delves into the complex realities of love, fame, and identity. His lines are tinged with vulnerability, revealing raw emotions that often remain hidden behind the façade of celebrity. Take, for example, the line “The one that I needed was Courtney from Hooters on Peachtree,” where Drake looks back on a past relationship with a sense of irony and introspection. Musically, the song benefits from its minimalistic production. Chilly Gonzales’ piano keys float above a restrained drum machine, allowing the lyrics to breathe. Jhené Aiko’s vocal contributions, elegant yet haunting, act as a foil to Drake’s introspective bars, complicating the song’s emotional textures.

“The Language” executes a sonic tableau that encapsulates self-assured swagger and contemplative vulnerability. The production, helmed by frequent collaborators Boi-1da, Vinylz, and Allen Ritter, provides a minimalist yet punchy framework. The bed of stuttering hi-hats and deep bass reverberates through the speakers, creating a sonic canvas that perfectly complements Drake’s musings on his place within the music industry and broader culture. The production sometimes swells to fill the empty spaces between his words as if punctuating his sentiments.

Yet, there’s room for contrasting viewpoints; one might argue that the track is less about lyrical intricacy and more about mood-setting, emblematizing a vibe more than a treatise. Whatever stance one takes, it’s clear that “The Language” exhibits a complex yet approachable work that adds texture to the ever-evolving narrative of one of contemporary music’s most influential figures.

One standout track, “Too Much,” features British musician Sampha, whose soulful crooning imbues the song with an emotional weight. Drake’s lyrics confront the complications of fame and the disconnect it brings with the people closest to him. Lines like “Don’t run from it, like H-Town in the summertime, I keep it 100” confront the disorientation of success, referencing Houston’s notorious heat as a metaphor for complex realities. The production, a blend of introspective keys and laid-back percussion, aligns perfectly with Drake’s vulnerability.

Transitioning from “Too Much,” we encounter “Pound Cake/Paris Morton Music 2,” a two-part epic featuring JAY-Z. What makes this song remarkable is its bravado balanced with introspection. JAY-Z flaunts his success while offering commentary on the unpredictability of the music industry. For instance, when JAY-Z says, “Cake, cake-cake, cake-cake, cake, 500 million, I got a pound cake,” he’s discussing the dual nature of wealth—its allure and its emptiness. The production switches between two different beats, a technique that aligns well with the song’s thematic duality, enriching the listening experience.

Then comes “All Me,” a collaboration with 2 Chainz and Big Sean that, by contrast, dives headlong into the opulence and swagger associated with rap culture. Each artist presents their unique perspective on fame and fortune. Drake’s lines like “I touched down in ’86, knew I was the man by the age of 6” reveal a predestined sense of greatness. Meanwhile, he adds levity with inherently humorous yet clever lines, such as “I’m on a roll like Cottonelle, I was made for all of this sh*t.” The production, handled by Key Wane with additional work from Noah “40” Shebib, features a pulsating beat and vibrant synths, creating a triumphant atmosphere.

In a music industry awash with momentary sensations and short-lived phenomena, Nothing Was the Same established itself as a standout moment for Drake. The album presented a portrait of an artist who was fully aware of his powers but still questioned the limits of his potential. It encapsulated a phase of his career marked by transformation and introspective contemplation, contrasted with a confidence that often borders on audacity.

While the album received its share of criticism, its significance in Drake’s discography and the larger hip-hop canon remains open to discussion, leaving ample room for different perspectives. Whether viewed as a masterpiece or a transitional project, its impact and artistry are beyond question, fostering enduring conversations about the fluidity of identity, the complexities of fame, and the ceaseless pursuit of artistic evolution.