Revisiting 2006 in Rap Music

The South had been knocking on the door for years. In 2006, it kicked the door off the hinges. Mainstream success meant compromise for most artists chasing radio play. A handful refused the bargain.

Atlanta, Houston, Miami, and New Orleans had spent the previous decade building infrastructure, developing sounds, and demanding respect from a genre that kept its capital in New York. OutKast opened the conversation with their 2003 Grammy sweep. Lil Jon turned crunk into a pop phenomenon. But 2006 marked the year when Southern dominance stopped being a trend and became the new normal. T.I. crowned himself King and made it stick, selling records at a pace that validated every boast. Young Jeezy’s The Inspiration confirmed that trap had real staying power. Rick Ross loomed from Miami with a voice and a persona that shaped the next decade of rap excess.

While snap music and ringtone rap saturated radio playlists, a parallel universe of uncompromising hip-hop continued to thrive beneath the surface. Clipse delivered Hell Hath No Fury four years late and lost none of its venom, Pharrell’s icy Neptunes production providing the perfect backdrop for the Thornton brothers’ cocaine dissertations. Ghostface Killah reconnected with the street narratives that made his name, proving that Wu-Tang’s lyrical legacy survived the clan’s commercial collapse. The Roots went darker than they’d ever gone, abandoning jazz-inflected optimism for the bleak textures of Game Theory. These albums chased permanence.

The anticipation surrounding Kingdom Come bordered on religious fervor. Shawn Carter used his hiatus to run Def Jam, sign Rihanna, and watch the genre evolve without him. His return carried impossible expectations, and the album itself divided critics and fans in ways none of his previous work had. But the commercial numbers silenced any doubts about his relevance. Nearly seven hundred thousand copies moved in the first week. JAY-Z’s presence still warped the industry around him, his guest spots commanding premium placement, his business moves drawing as much coverage as his bars. Even a flawed album failed to diminish his gravitational pull.

Dwayne Carter spent 2006 flooding the market with material that might have buried lesser talents. The Dedication 2mixtape dropped in spring and announced that Wayne had become a legitimate threat, his alien punchlines and syrupy drawl birthing an entirely new style. Peers watched with admiration and alarm as he stole every song he appeared on. The critical consensus that Wayne was the best rapper alive began crystallizing during these twelve months, setting up the commercial explosion that Tha Carter III delivered two years later. His velocity became the standard against which hungry MCs measured themselves.

James Yancey’s death in February transformed his final instrumental album from a career statement into a eulogy. The record arrived already mythologized, its chopped soul samples and off-kilter drum patterns taking on new weight with each passing month. Donuts rewrote the rules for what instrumental hip-hop accomplished, its emotional depth achieved entirely without words. Producers who came after devoted years to decoding its warmth, its melancholy, its refusal to resolve into easy feelings. Dilla’s influence had always been enormous. His absence made it permanent.

Hip Hop Is Dead arrived carrying all the contradictions its title promised. Nas attacked ringtone rap, snap music, and the general drift toward content-free party tracks with the venom of someone personally wounded by the culture’s trajectory. Critics debated whether he was right or simply aging out of relevance. The album forced a reckoning with questions the genre had been avoiding. What did authenticity mean when the most popular sounds came from regional scenes New York had ignored for years? Did lyrical complexity stand a chance in a market that rewarded hooks over bars? These debates persisted long after 2006 ended.

The year’s breakout stars and underground heroes defined the late 2000s and early 2010s in ways no one fully anticipated. Rick Ross built Maybach Music Group into a launching pad for multiple careers. Lupe Fiasco proved that lyrical ambition still had commercial potential, even if he remained the exception. The Clipse’s influence spread through a generation of rappers who heard Hell Hath No Fury and understood that minimalism and menace coexisted. T.I.’s throne-claiming swagger became the template for Atlanta MCs who followed. And Lil Wayne’s relentless 2006 output was merely prologue to the three-year run that made him the dominant figure in rap. The year produced the future.

The Breakout Rap Stars of 2006

Yung Joc

A single whistle loop conquered the summer. “It’s Goin’ Down” arrived with a production hook so simple and so infectious that resistance proved futile, its snap-music bounce saturating radio, clubs, and ringtones all season long. The song made Jasiel Robinson a star before most listeners knew his name, his ad-libs and bouncing flow secondary to that inescapable Nitti Beatz instrumental. Yung Joc came out of College Park, Georgia, part of Atlanta’s sprawling constellation of satellite cities that fed the region’s rap economy. Bad Boy South signed him after the single began circulating, Diddler recognizing the commercial potential in snap’s minimalist template. The debut album New Joc City followed the hit’s success, stacking similar productions and party-ready choruses designed for immediate consumption. Snap music’s commercial window opened and closed within eighteen months, and Yung Joc’s stardom tracked that arc precisely. The brevity of his peak didn’t diminish what he accomplished during it.

Rick Ross

Miami had waited years for a new kingpin. Trick Daddy and Pitbull carried the city’s flag through the early 2000s, but neither projected the specific brand of opulence and menace that William Roberts II would soon embody. When “Hustlin’” began flooding South Florida in early 2006, the voice alone announced something different: a baritone growl draped over The Runners trunk-slapping horns, promising cocaine and consequence in equal measure. The persona materialized fully formed. Ross presented himself as a drug lord surveying his empire, his lyrics dense with weight measurements, luxury brands, and thinly veiled threats. Whether the autobiography held up to scrutiny mattered less than the conviction he brought to every bar. The character work was immaculate, his delivery suggesting a man who had seen things he would never completely describe. Def Jam won the bidding war, and Port of Miami dropped in August to immediate commercial success. A decade later, Ross would stand among the era’s most successful artists, his Maybach Music Group imprint a launching pad for multiple careers. None of that was guaranteed in 2006, but the foundation he poured that year held every brick that followed.

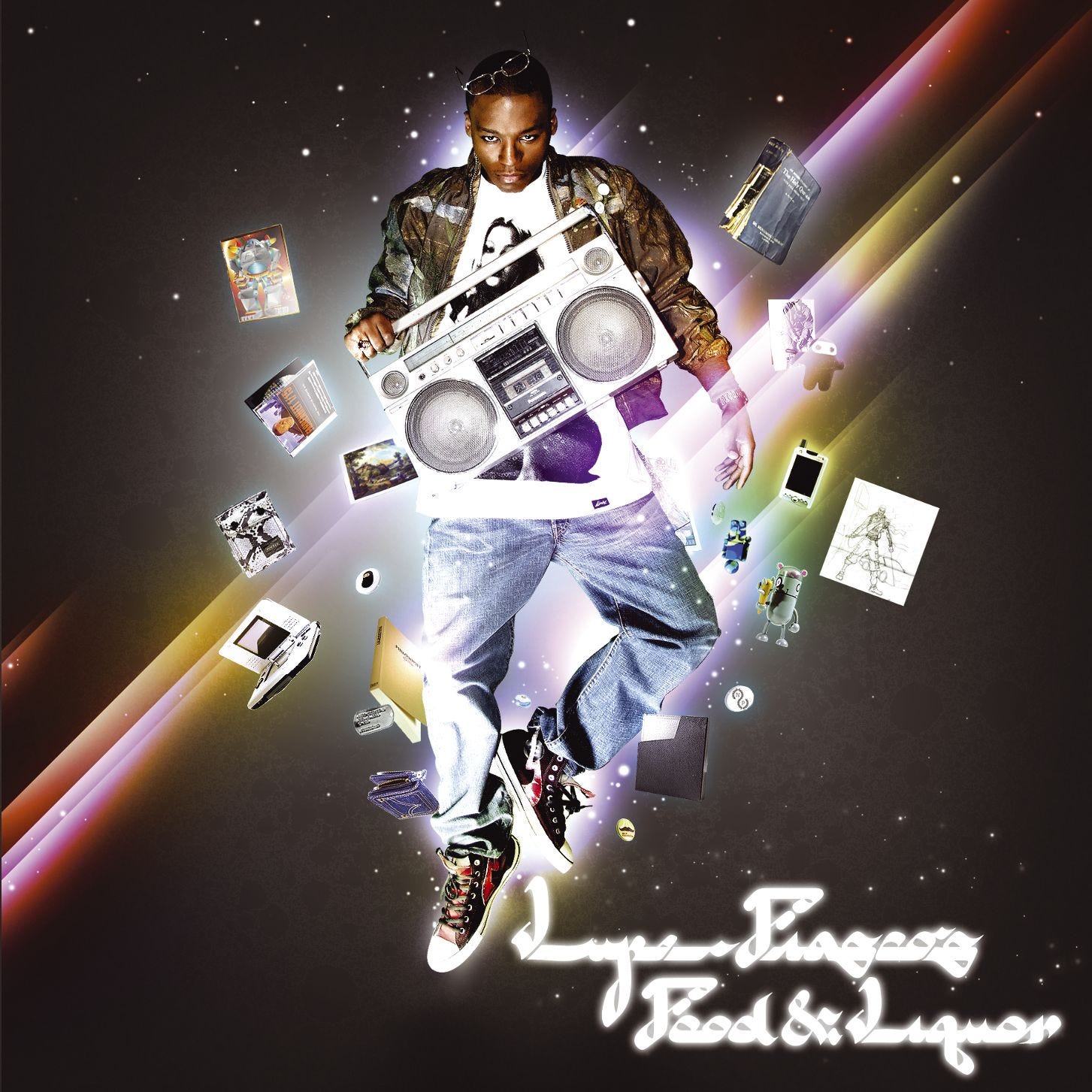

Lupe Fiasco

Kanye West’s “Touch the Sky” introduced an anomaly. Amid West’s triumphant horns and Curtis Mayfield sample, a Chicago rapper named Wasalu Jaco delivered verses stuffed with references and wordplay that required a decoder ring to unpack. The feature made clear that someone uncommonly strange had entered the mainstream conversation, a lyricist whose density bordered on sabotage. Atlantic released Food & Liquor in September after months of delays and label disputes. The album rewarded the patience. Lupe constructed songs as puzzles, hiding meaning inside nested metaphors and extended conceits that revealed new layers on each listen. A track about a toy robot became a meditation on consumerism. A love song doubled as political commentary. Nothing worked on just one level. Critical acclaim came swiftly and emphatically, the album landing on year-end lists and earning Grammy nominations. Lupe’s debut suggested that lyrical ambition still had a place in a market increasingly dominated by snap chants and street anthems. He was the exception, not the rule, but exceptions matter.

The Pinnacle Rappers of 2006

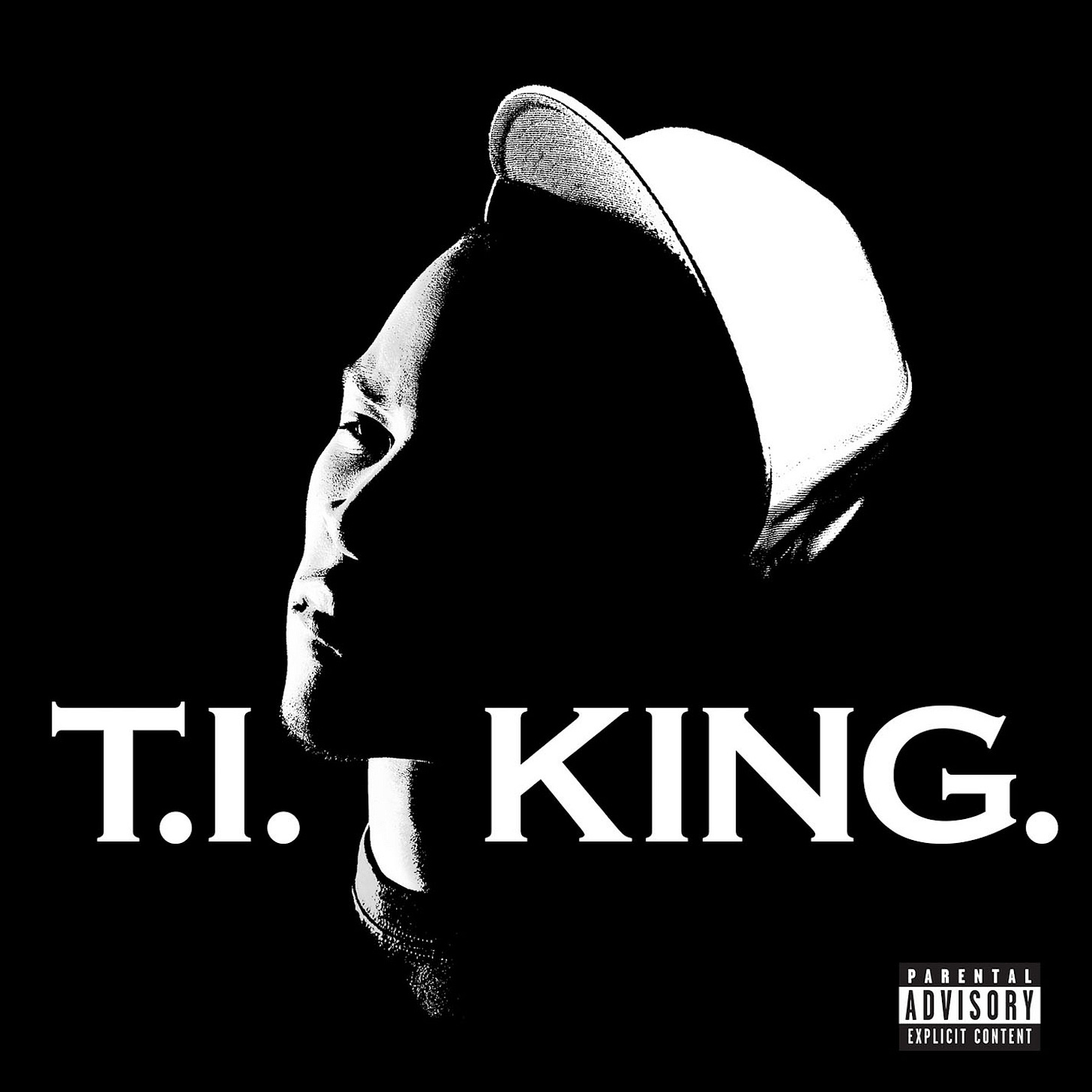

T.I.

Years of near-misses and regional respect had positioned T.I. at the threshold of mainstream dominance, and King finally kicked the door open. The Atlanta rapper's third and fourth albums had generated heat in the South, but national recognition kept slipping away at crucial moments. This year, nothing slipped. He planted his flag at the center of hip-hop's commercial axis, selling records at a pace that validated every boast he'd been making since his debut. His presence on radio and television became inescapable, his face attached to hit singles, magazine covers, and a cultural shift that would redefine what Southern rap could accomplish. Atlanta had produced stars before him, but none had claimed the throne with such explicit ambition. The year belonged to him in a way it rarely belongs to any single artist, and the decade that followed would bear his fingerprints on nearly every chart-topping Southern MC who came after.

JAY-Z

Retirement lasted three years. Shawn Carter had stepped away from recording in 2003, positioning The Black Album as a farewell gesture and pivoting toward executive responsibilities at Def Jam. The hiatus only amplified anticipation for his inevitable return, and speculation about a comeback album consumed hip-hop media throughout 2005 and into the following year. Kingdom Come arrived in November carrying impossible expectations. JAY-Z was now a businessman first and a rapper second, or so the narrative went, and skeptics wondered whether corporate duties had dulled his competitive edge. The album debuted at number one and moved nearly seven hundred thousand copies in its first week (yeah, yeah, we know), figures that silenced questions about his commercial viability even as critical reception proved more divided. What distinguished his 2006 from lesser comeback attempts was the sheer gravitational pull he still exerted. JAY-Z’s presence warped the industry around him. His guest spots commanded premium placement, his cosigns launched careers, and his business moves drew as much coverage as his bars. The rapping itself showed flashes of his peak-era brilliance alongside more relaxed, reflective passages that acknowledged his position as an elder statesman.

Lil Wayne

Nobody in 2006 worked harder or released more material. While others measured output in albums, Lil Wayne measured his in mixtapes, features, and loosies that flooded the internet with staggering regularity. The sheer volume would have buried a lesser talent under its own weight. Wayne only got sharper. Hot Boys nostalgia had defined him for years, but Tha Carter II’s late-2005 release sent aftershocks rippling across the following year as Wayne’s reputation swelled into something new. He transformed from Birdman’s protégé (they released Like Father, Like Son in the same year) into a stranger, more singular figure, an MC whose alien punchlines and syrupy drawl birthed an entirely new style. The Dedication 2 mixtape dropped in the spring and cemented his status as the most dangerous guest verse in rap. Peers watched him with a mixture of admiration and alarm. Wayne’s relentless output meant he was everywhere at once, unavoidable on radio, on the internet, on other people’s albums. The absurdist wordplay and left-field similes spread like a virus through the rap underground, younger MCs absorbing his cadence shifts and attempting his punchline density. Imitation proved the sincerest form of surrender.

Classic Rap Albums of 2006

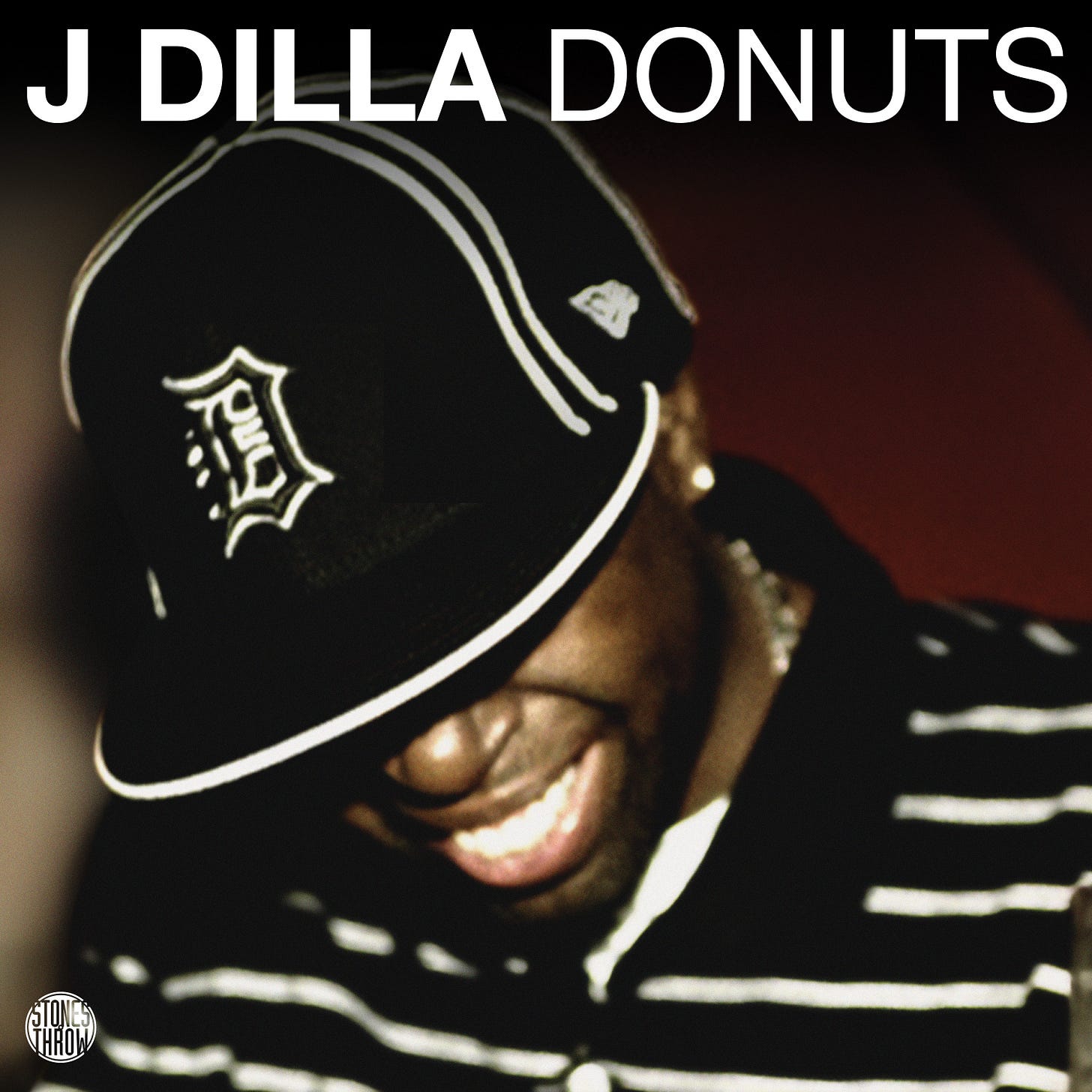

J Dilla, Donuts

For more than a decade, James Yancey operated as one of hip-hop’s most sought-after beatmakers, his fingerprints visible across records by A Tribe Called Quest, Common, De La Soul, and dozens of others. Serious rap listeners revered his production instincts, though wider fame eluded him throughout his career. In 2005, illness began consuming his final years. Yancey was hospitalized with a rare blood disease called thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, compounded by lupus. He continued making beats from his hospital bed, loading samples into his MPC and arranging them during the diminishing hours his condition allowed. The label released it on his thirty-second birthday. He died three days later. The album consists entirely of instrumentals, brief fragments assembled from soul, funk, and pop samples manipulated into something unrecognizable from their sources. Yancey simply let the samples speak, cutting them into shards that communicate something beyond their original contexts.

The production techniques on Donuts emphasize disruption and surprise over smoothness. Yancey chops vocal phrases mid-word, flips samples backward, stacks unlikely combinations, and lets beats dissolve before they settle into predictable patterns. They blur individual tracks together, creating a continuous suite rather than a collection of discrete songs, with drums punching through at unexpected moments and melodies flickering into view only to vanish within seconds. The whole record feels like a fever dream assembled by someone racing against a clock only he could see. Donuts transformed instrumental hip-hop’s possibilities and permanently altered how producers approached sampling. The album acquired near-sacred standing almost immediately, cited by beatmakers across multiple generations as a reference point for adventurous, affecting production. Yancey’s final statement proved that hip-hop instrumentals could carry the weight of a dying man’s last message to the world, and that pure sound, shorn of words, could convey profound grief and defiant joy simultaneously.

T.I., King

As the self-proclaimed King of South, Clifford Harris had spent years circling the perimeter of mainstream rap stardom. His 2001 debut I’m Serious stalled commercially despite its regional pedigree, and his follow-up Trap Muzik performed well enough in 2003 to keep him afloat without catapulting him into the upper tier occupied by 50 Cent and Ludacris. By 2004’s Urban Legend, the Atlanta rapper had sharpened his formula considerably, landing a pair of substantial radio singles and strengthening his grip on the Dirty South market. Still, a ceiling persisted. T.I. remained a respected regional heavyweight who hadn’t yet cracked the national conversation the way his ambitions demanded. King shattered that barrier entirely. Released in the same week as ATL, its title spelling out the rapper’s intentions without apology. T.I. positioned himself as trap music’s regent at a moment when the subgenre was spreading from Atlanta’s strip malls and parking lots into the wider American consciousness. The record turned an underground Southern style into a dominant commercial force, proving that coke-rap could move units at pop scale without diluting its street-level origins.

The production across King balances menace with accessibility in ways few trap albums had managed before. DJ Toomp contributes several tracks built on ominous synthesizer swells and clattering 808 percussion, giving T.I. room to toggle between boastful declarations and more reflective street narratives. Various producers from DJ Toomp, Mannie Fresh, and Just Blaze supply beats that lean closer to traditional boom-bap, allowing the rapper to demonstrate his technical versatility outside his home region’s sonic template. Throughout, T.I. raps with clipped authority, his delivery bending syllables around triplet patterns that would later become trap’s rhythmic default. His fourth LP confirmed T.I. as a genuine commercial juggernaut and helped establish Atlanta’s permanent position at hip-hop’s commercial center. The album’s success paved a route for a generation of trap-indebted Southern rappers who would dominate the following decade’s charts. Few records have so cleanly marked both a personal and regional breakthrough, and fewer still have aged as gracefully while retaining their original street credibility.

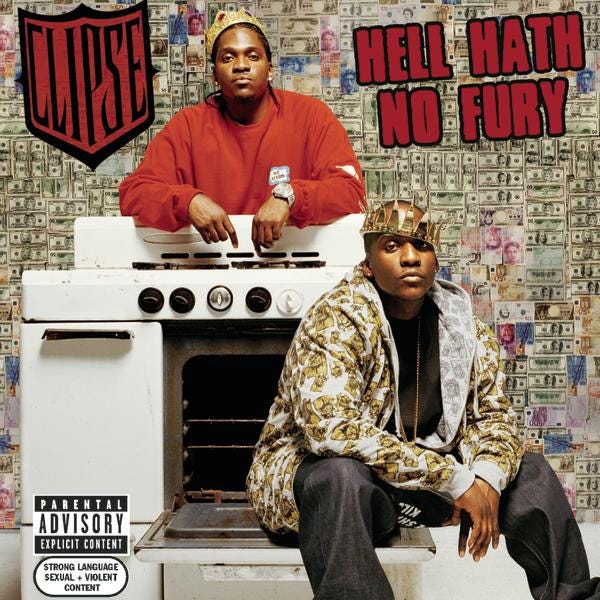

Clipse, Hell Hath No Fury

Pusha T and Malice had already proven themselves capable of crafting a classic with 2002’s Lord Willin’, a record that merged Virginia Beach’s gritty cocaine narratives with Neptunes production at its commercial peak. The album went gold and spawned recognizable singles, but label dysfunction at Jive Records (at the time of this writing, it has been revived) stranded the brothers in contractual limbo for nearly four years, during which mixtapes circulated (the second volume of We Got It 4 Cheap is immaculate) and frustration mounted. When clearance finally came to release a sophomore effort, the duo had accumulated enough resentment to fuel something considerably darker than their debut. Hell Hath No Fury surfaced in November 2006 as an unrelentingly bleak dispatch from the Virginia coke trade. The Clipse intensified the drug-dealing subject matter that defined their earlier work while stripping away any remaining traces of commercial compromise. Every verse drips with cold-eyed specificity about the mechanics of the crack business, delivered in Pusha T’s sneering baritone and Malice’s more measured, morally conflicted tone.

Without Chad Hugo, Pharrell constructed beats that abandoned the bouncy radio-friendly sound that had characterized much of their earlier production. Instead, the Neptunes (still credited in the liner notes) delivered skeletal arrangements dominated by grinding synthesizers, stuttering percussion, and vast stretches of negative space. The sparse instrumentation forced attention onto the brothers’ wordplay, their internal rhyme schemes and multisyllabic constructions occupying the foreground rather than competing with melodic hooks. Nothing on the album chases crossover appeal. The pair seemed intent on punishing anyone expecting a retread of Lord Willin’s more accessible moments. The second album’s uncompromising approach to coke rap laid groundwork for a subsequent wave of street-oriented rappers who prioritized lyrical density over mainstream palatability. It remains among the most celebrated underground records of its era, a document of artistic stubbornness that refused to soften its edges despite years of industry interference.

Essential Rap Albums of 2006

Lupe Fiasco, Food & Liquor

Chicago had produced rap stars before Lupe Fiasco, but none quite like him. Kanye West opened doors for introspective Midwestern MCs who favored backpacks over bandanas, and Lupe walked through carrying a skateboard and a notebook full of dense, knotted verses. His guest appearance on West’s “Touch the Sky” announced a lyricist whose complexity bordered on opacity, a rapper more interested in stacking metaphors than chasing radio spins. Rather than coast on that early buzz, Lupe constructed an album that rewarded sustained concentration. He built songs around singular conceits and rode them to their logical ends, layering extended metaphors that only fully registered on second or third listen. His flow never settled into predictable cadences, shifting rhythms mid-bar and burying punchlines inside nested clauses. He matched those eclectic backdrops with subject matter that ranged from skateboard culture to Middle Eastern politics, refusing to confine himself to any single lane. Chicago gained another distinct talent, and a generation of technically ambitious rappers who valued wordplay over hooks would trace their lineage back to Food & Liquor. Lupe’s example taught younger MCs that accessibility and complexity need not be mutually exclusive.

Ghostface Killah, Fishscale

While Wu-Tang’s commercial standing crumbled during the early 2000s, Dennis Coles kept releasing solo records that maintained critical respect even as sales dwindled. Most of his clanmates struggled to recapture their mid-nineties footing. Ghost never stopped working. On Fishscale, he reconnected with the cocaine narratives that defined his earliest material while sharpening his storytelling considerably. Drug tales unfolded with cinematic specificity, packed with brand names, dollar amounts, and geographic details that lent his fiction the weight of documentary. Ghost’s slang stayed impenetrable to casual ears, a private language of nicknames and references that repaid close listening. MF DOOM, J Dilla, and Pete Rock all handled beats, chopping soul samples and pitching them in ways that recalled peak-era RZA yet never merely imitated him. Ghost’s voice cut across every track with gruff authority, toggling from hushed menace to frantic enthusiasm within single verses, giving the varied textures a commanding center of gravity. In a ringtone-dominated market, Fishscale made the argument for golden-age aesthetics with brutal conviction, keeping traditional East Coast lyricism alive during a period when Southern styles commanded mainstream attention.

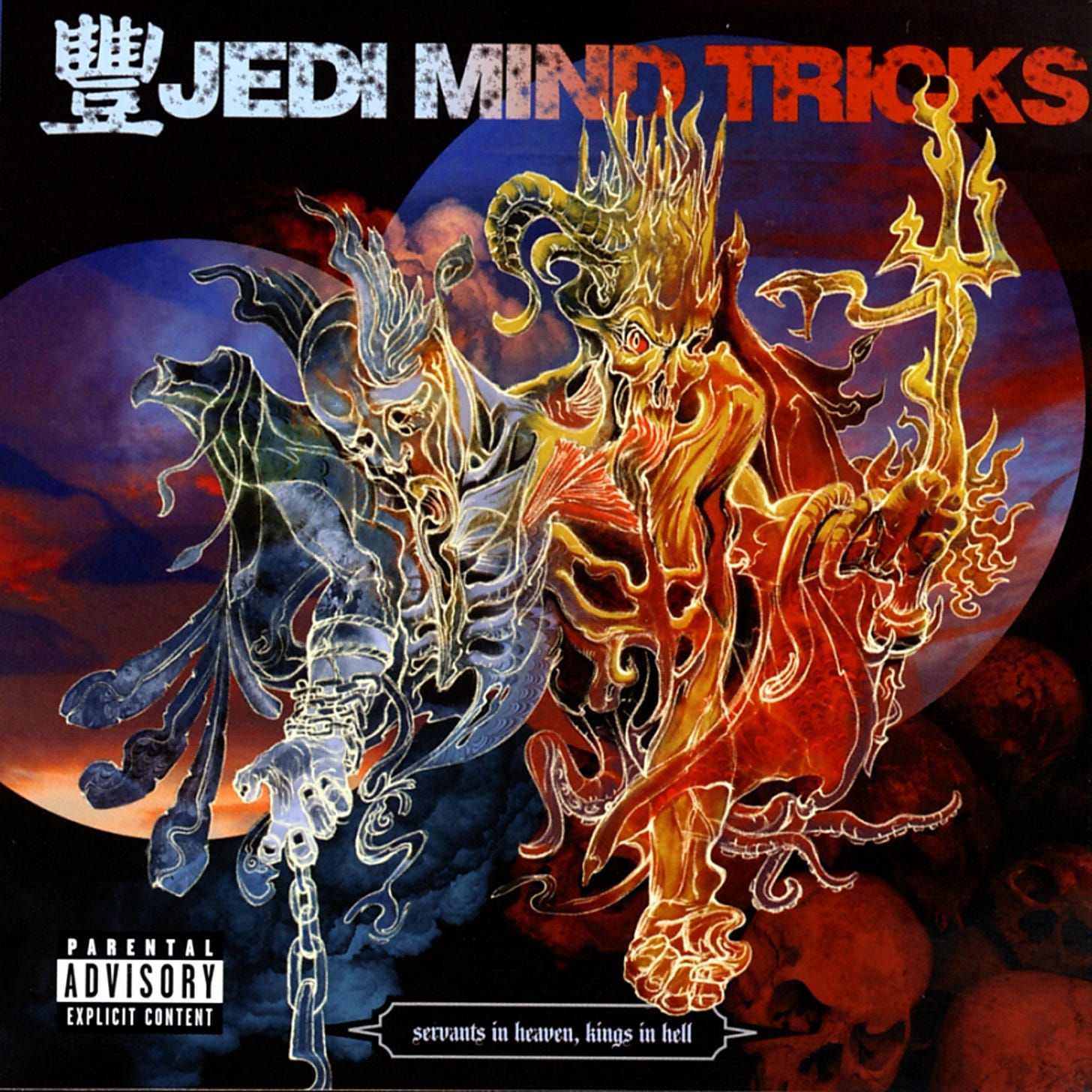

Jedi Mind Tricks, Servants in Heaven, Kings in Hell

For nearly a decade, Vinnie Paz and producer Stoupe the Enemy of Mankind had cultivated a devoted Philadelphia following on independent releases that trafficked in conspiracy theories, theological fury, and relentless lyrical aggression. Their fanbase grew via word of mouth and internet message boards instead of radio play or magazine coverage. Their most focused and accessible work sacrificed nothing of that core identity. Paz delivered his paranoid street scriptures with renewed ferocity, his gravel-voiced flow hammering syllables into submission. Guest appearances from GZA, Percee P, and Sean Price added variety while preserving the album’s oppressive atmosphere. Servants in Heaven, Kings in Hell put a long-standing underground theory beyond dispute. Major label support and mainstream cosigns were unnecessary for reaching substantial audiences, and the album brought Jedi Mind Tricks to their commercial peak while validating the independent distribution model that sustained them.

The Roots, Game Theory

Something had darkened inside The Roots. After more than a decade of defying categorization with live instrumentation and elastic song structures, the Philadelphia collective abandoned much of their earlier musical complexity for Game Theory, opting for sparse textures and grim lyrical content instead. Black Thought addressed systemic violence, political corruption, and personal trauma with unsparing directness, dropping the playful wordplay that sometimes lightened previous efforts. His writing carried new urgency, each verse pressing closer to raw anguish. Questlove built drum patterns that emphasized tension over groove, threading distorted guitars, dissonant keyboards, and unsettling silences into the arrangements. The album solidified The Roots’ reputation as hip-hop’s most restlessly ambitious band. By engaging with despair and dread while sidestepping exploitation and sensationalism, Game Theory influenced the next wave of artists who sought to push the genre toward more challenging emotional ground.

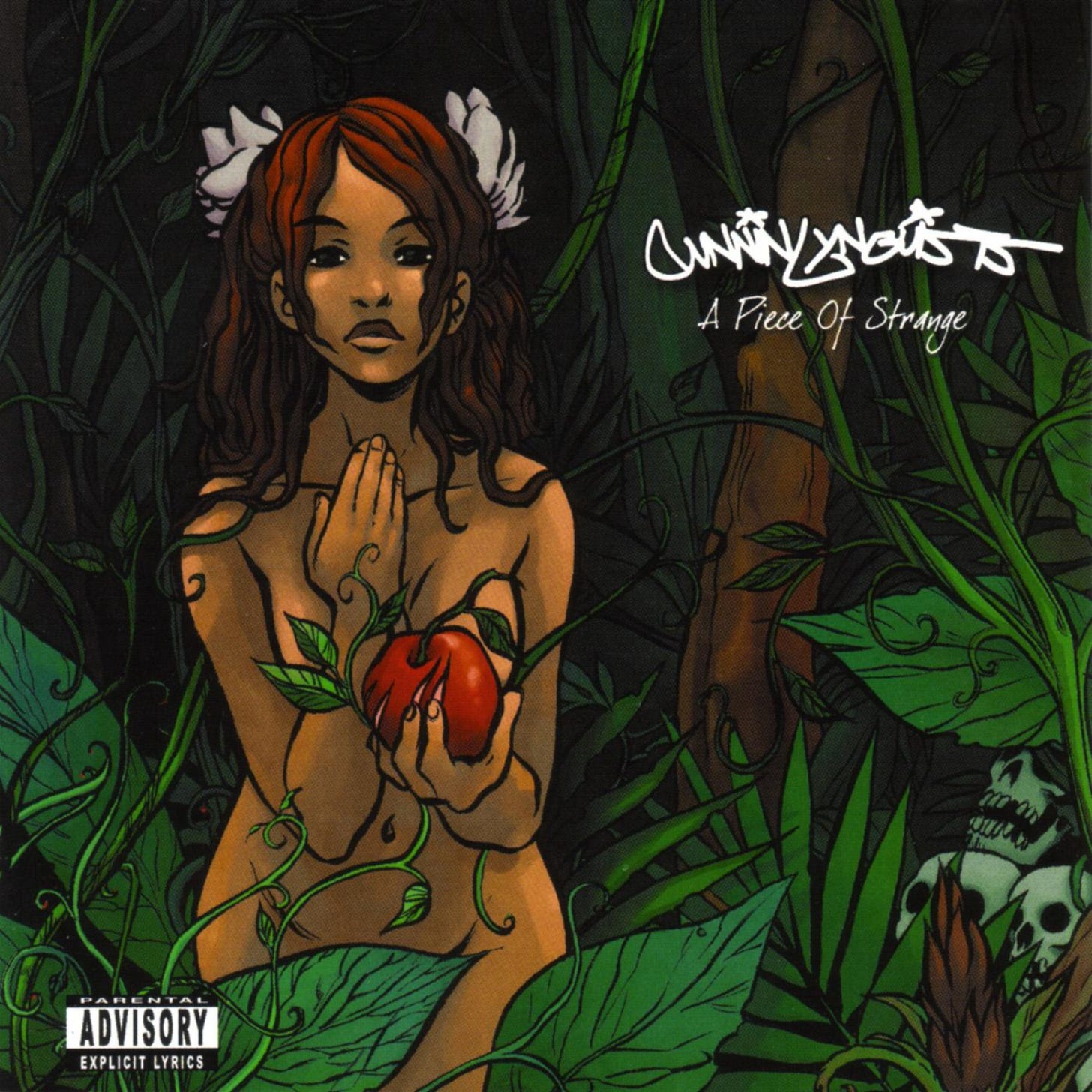

CunninLynguists, A Piece of Strange

Few hip-hop concept albums from any era achieve the narrative cohesion of A Piece of Strange. Every track connects to what precedes and follows it, threaded together by recurring characters and interlocking themes about faith, doubt, temptation, and redemption. The listening experience resists shuffling or cherry-picking singles entirely. That ambition came from an unlikely source. The Kentucky trio of Deacon the Villain, Kno, and Natti lacked the regional cachet that might have drawn notice, hailing from a state with no existing hip-hop scene and no clear stylistic identity to claim. Their previous records earned praise from underground publications but failed to penetrate wider consciousness. Kno assembled soundscapes from Southern soul, gospel, and psychedelic rock that enhanced the album’s conceptual weight. His beats refused to separate from their lyrical content, functioning as narrative instruments instead of mere backdrops. A cult following that endured across later releases grew from this album, and A Piece of Strange laid the blueprint for hip-hop concept records that prioritized thematic coherence over hit potential.

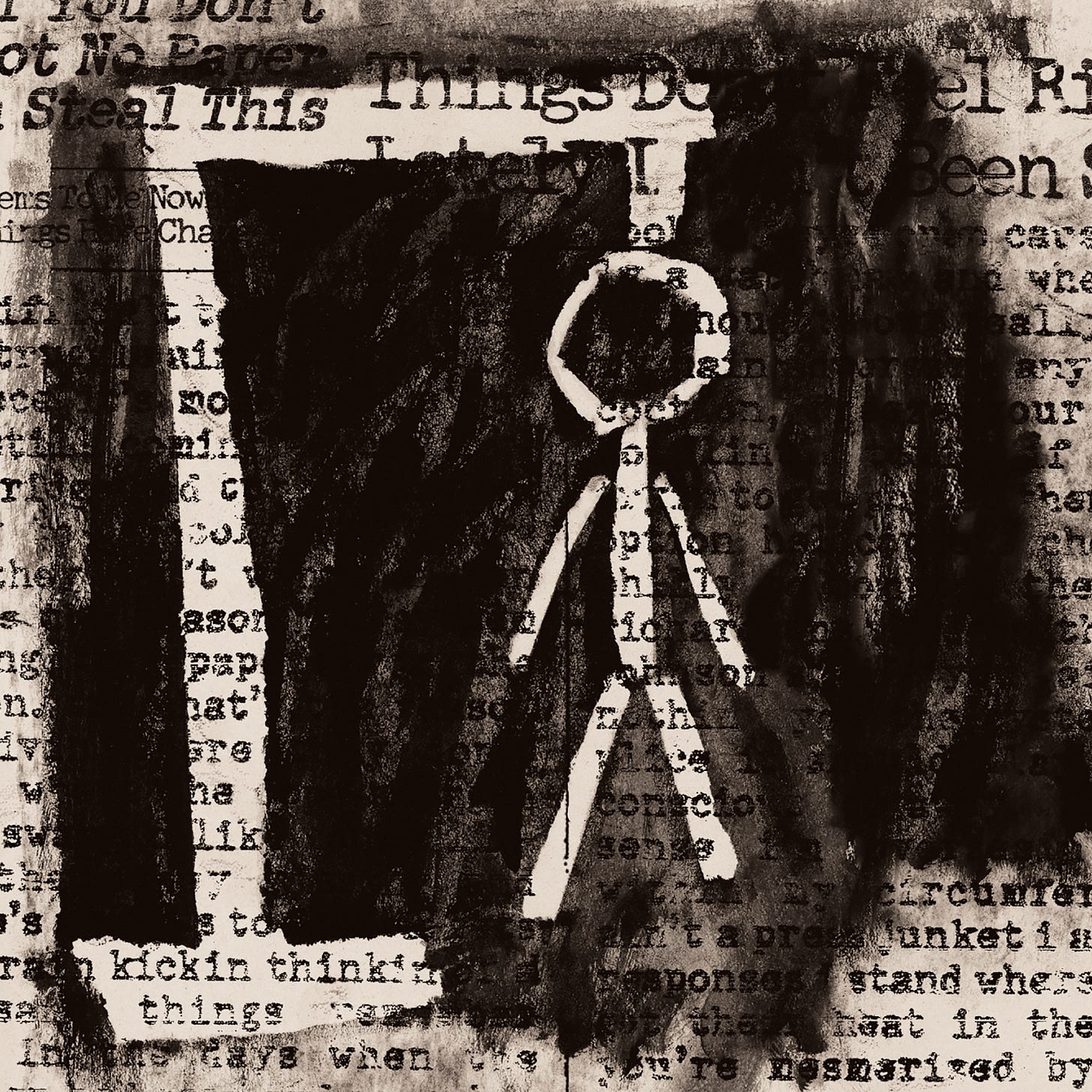

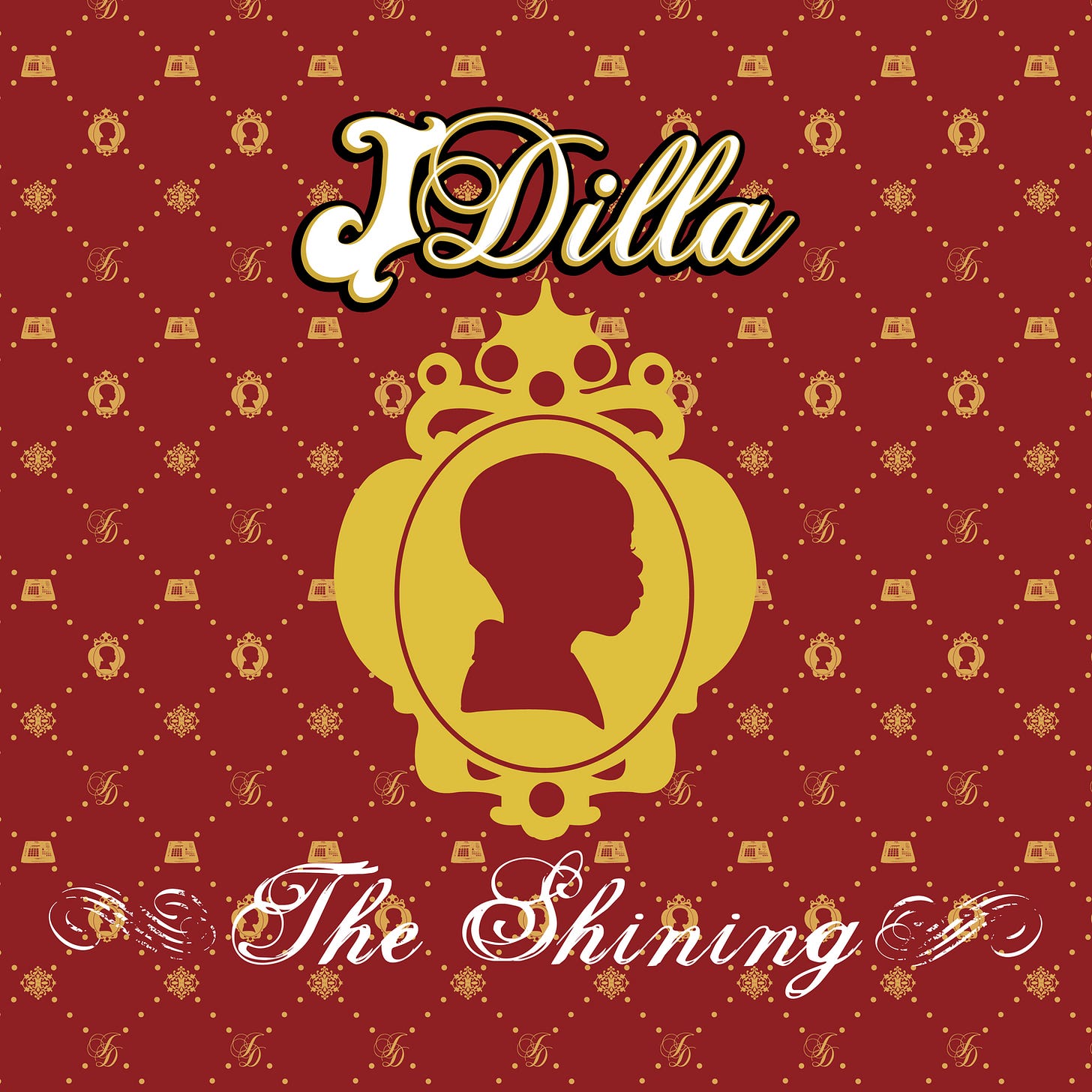

J Dilla, The Shining

James Yancey’s death left unfinished material scattered across hard drives and recording sessions. Donuts had been completed in time for him to witness its release, but other projects remained in various states of incompletion. The Shining compiled tracks Dilla had been assembling for a proper follow-up to his vocal debut, supplemented with verses he’d recorded over the years. Here was a different Dilla than the one memorialized in instrumental work. He rapped extensively, his voice relaxed and conversational over beats that favored warmth over experimentation. Common, Busta Rhymes, Pharoahe Monch, and D’Angelo filled out songs that Dilla might have completed differently given more time. Accessible soul sampling and smooth grooves replaced the disruptive chops that characterized his final instrumental work. Dilla the singer and rapper surfaced on several tracks, his thin voice surprisingly effective against the plush backings he constructed. Work that might otherwise have stayed in vaults found an audience, and the album complicated tidy accounts of Dilla’s legacy by revealing an MC who might have pursued vocal albums had his health permitted.

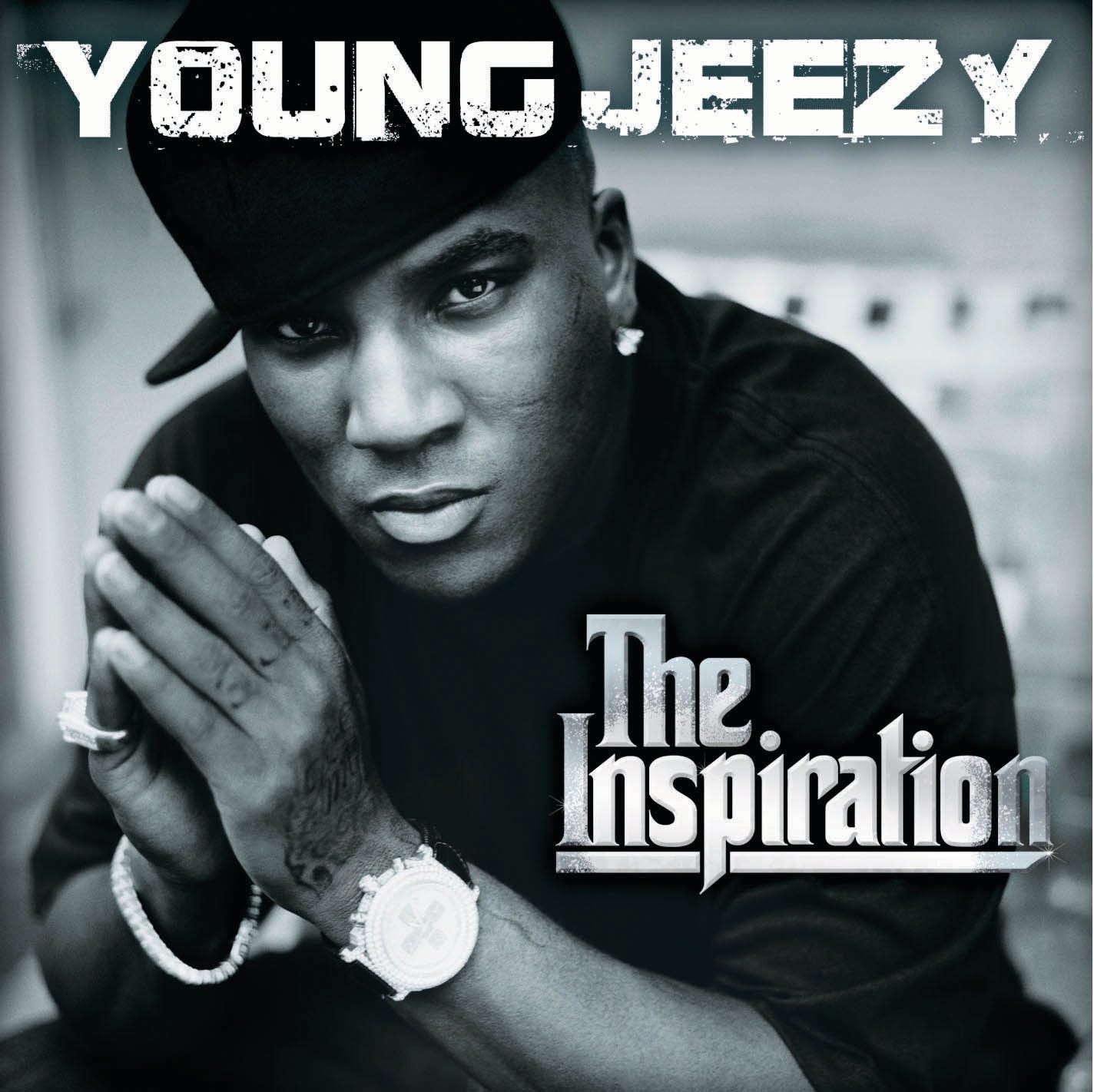

Young Jeezy, The Inspiration

One-album wonders littered Southern rap history. Young Jeezy had signaled trap music’s commercial viability with his 2005 debut, but durability was unproven, and skeptics waited to see whether he could sustain momentum beyond a single formula. He chose consolidation over reinvention. Jeezy committed further to the street anthems and motivational hustler tales that powered his breakthrough, tightening the songwriting around hooks designed for maximum impact. His ad-libs grew more pronounced. His beats hit harder. Shawty Redd and DJ Toomp returned to supply production that maintained ominous synthesizer beds and booming 808 patterns while incorporating more prominent melodies, expanding Jeezy’s sonic territory while staying true to his core sound. Trap’s dominance over mainstream rap for the decade that followed owed a debt to this album. The Inspiration confirmed Jeezy as a permanent fixture rather than a passing novelty, and its commercial success validated a regional style that would eventually conquer global pop.

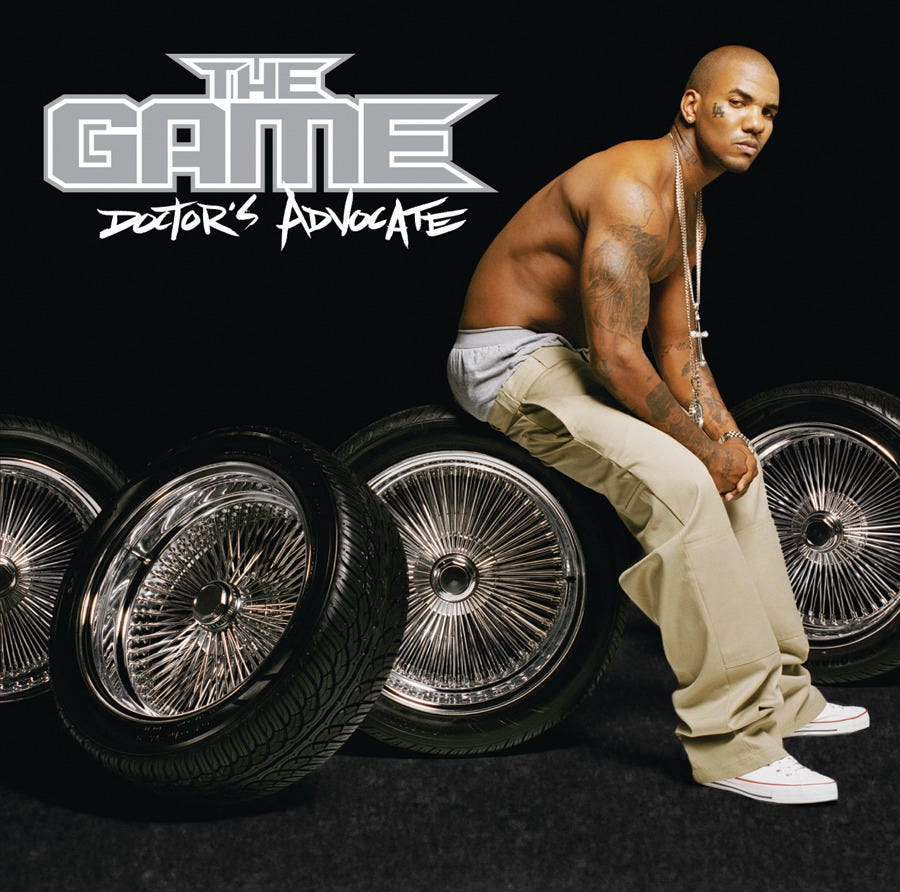

The Game, Doctor’s Advocate

50 Cent’s blessing and Dr. Dre’s production had guaranteed Jayceon Taylor’s debut commercial success but complicated assessments of his individual talent. When Game’s relationship with G-Unit collapsed in spectacular public fashion, many predicted his career would follow. Without Dre and 50’s support, could he survive? He assembled an album without a single Dre beat. will.i.am, Kanye West, Hi-Tek, and Scott Storch occupied the vacuum, and the resulting record made clear that Game could command attention on sheer rapping ability rather than high-profile affiliations. Newfound confidence saturated the writing. Game addressed the G-Unit fallout directly on several tracks, channeling real anger into memorable disses. His flows had grown more varied, his punchlines sharper, his West Coast nostalgia and name-dropping now carried by technical improvement instead of borrowed credibility. Doctor’s Advocate served as proof of concept for a beleaguered West Coast, keeping a regional tradition commercially viable during a fallow period for California hip-hop and a market dominated by Southern sounds.

Tame One, Spazmatic

Production duo Xing N Fox assembled an album of deliberately unhinged beats for a rapper whose reputation hinged on unhinged delivery. The pairing made perverse sense. Tame One had spent the late nineties as half of the Artifacts, crafting dense rhyme schemes over boom-bap templates, and the years since had scattered his output across compilations and guest spots. Spazmatic announced itself as intentionally difficult. Xing N Fox built tracks from pounding, magnified drums that refused conventional melodic sweetening, creating soundscapes that resembled early electro filtered through damaged equipment. The production techniques recalled rap’s founding era but pushed further into abstraction. Tame matched that sonic aggression with writing that veered between stoner humor, dense internal rhyming, and unexpected emotional transparency. His pinched, instantly recognizable delivery sliced across the varied production with consistent personality, referencing obscure cartoons, breakfast cereals, and drug paraphernalia with equal enthusiasm. The underground was growing increasingly serious, and Spazmatic refused to follow suit. The record preserved Tame One’s name and gave fans an album where fun and lyrical craft coexisted, grinning at every turn.

Plan B, Who Needs Actions When You Got Words

Ben Drew operated completely outside American hip-hop circuits. The East London artist assembled a sound from UK garage, grime, and acoustic soul traditions that owed little to the Southern and East Coast styles dominating American charts. His accent alone guaranteed minimal stateside penetration. What distinguished him from peers in the UK scene was unguarded vulnerability. Drew wrote about council estate life, failed relationships, and working-class frustration with observational precision, avoiding both glorification and condescension. His writing placed audiences inside cramped flats and dodgy pubs with novelistic detail. He toggled between sparse acoustic settings and grimier electronic beats, singing as often as he rapped. His instrument carried real melodic ability that separated him from MCs who merely approximated singing. Who Needs Actions When You Got Words carved space for a distinctly English approach to rap, one that owed nothing to American templates. Subsequent UK artists would expand considerably on the methods Drew pioneered here.