Revisiting the Year 1978 in R&B

Stitch these moments together and you get a year that didn’t add chapters to R&B’s saga but opened entirely new plotlines.

R&B’s 1978 diary reads like a hinge in the genre’s story—one page still stamped with the lush orchestration of disco, the next scribbled in scratchy funk guitar, Linn-drum prototypes, and a teenage Minneapolis prodigy hunched over every instrument he could find. The year’s best records converged on the dance floor, yet each offered a different way forward: Rick James set Motown on fire with hemp-scented punk-funk; Chaka Khan turned feminist affirmation into a strings-and-congas anthem; and Prince quietly redrew the rulebook on studio self-sufficiency. Even legacy acts such as the Isleys and Patti LaBelle were busy retooling their sound for bigger stages and longer nights, proving nobody was too established to evolve.

Just as important, 1978 broadened the faces—and voices—of R&B. Female-fronted bands like A Taste of Honey put slap-bass prowess in the hands of Black women, while Cheryl Lynn’s gospel-bolted belt guaranteed hard-charging disco-funk could still hit like the holiness of Sunday morning. Gloria Gaynor, meanwhile, offered dance-floor catharsis so potent it would become an enduring civil-rights soundtrack. Stitch these moments together and you get a year that didn’t add chapters to R&B’s saga but opened entirely new plotlines.

Certified Classics in 1978

One Nation Under a Groove, Funkadelic

George Clinton’s P‑Funk mothership touched down with a proposition: liberation through collective rhythm. Recorded partly on tour, the album welded Hendrix‑grade guitar distortion, gospel call‑and‑response, and Motown‑steeped bass lines into a manifesto that funk could be as cosmic as prog‑rock yet as communal as a block party. The title cut’s elastic one‑chord vamp invites listeners to chant rather than merely listen, collapsing the distance between stage and floor.

That participatory spirit proved contagious. Hip‑hop’s architects looped P‑Funk riffs so often that by the early ‘90s Clinton’s catalog functioned as a secret backbone for West‑Coast rap; Ice Cube even drafted Clinton himself for “Bop Gun,” reinforcing the intergenerational handshake. The album’s talk‑box inflections and anthem‑scale choruses also resurfaced in the G‑funk era, while neo‑soul bands like The Roots cite it as proof R&B can be fiercely political without sacrificing groove.

Beyond music, the record’s imagery—Afrofuturist cartoons, utopian slogans—helped frame Black cultural expression as forward‑looking rather than archivist. Festivals, sneaker collabs, and even tech conferences borrow its “one nation” language to signal inclusive creativity. Few albums better demonstrate how a bass line can double as a social contract.

Is It Good to Ya, Ashford & Simpson

Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson were already revered songwriters, but this LP showed they could channel marital chemistry into dance‑floor architecture. Released in mid‑1978, it pairs devotional lyrics with rhythm‑guitar chanks that were clearly informed by the previous winter’s disco boom. “It Seems to Hang On” glides on syncopated congas and a sighing string pad, illustrating how sophisticated adult R&B could still move bodies at 120 BPM. Longevity arrived through interpolation. Zhané’s “Request Line,” Yung Gravy’s “Splash Mountain,” and multiple house edits flip the original’s guitar lick or Nick & Val’s unison refrain, underscoring how pliable the compositions remain for beatmakers chasing warmth. Teddy Pendergrass quickly covered the title track, solidifying its place in the canon of songs that treat commitment as a groove, not just a lyric.

Culturally, the album offered a counter‑narrative to the era’s king‑of‑the‑nightclub archetype: here was a Black married couple singing about mature love without losing sensual spark. Their aesthetic—silk suits, gospel‑stacked harmonies—became a template for later duos from René & Angela to Kindred the Family Soul. The record’s balance of sparkle and stability keeps it echoing wherever R&B wrestles with adulthood.

C’est Chic, Chic

Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards had already sharpened a minimalist disco vocabulary, but the follow‑up perfected it. “Le Freak” opens with a clipped guitar harmonic that feels like a light switch for the whole dancefloor; “I Want Your Love” threads swirling strings through a walking‑bass ostinato, marrying orchestral sweep to street‑corner funk. The album’s sequencing is taut: every transition mimics a DJ mix long before beat‑matching ruled clubs.

Its after‑effects are immeasurable. Rodgers’ right‑hand 16th‑note pattern became a core guitar study for R&B session players, while hip‑hop relied on Chic’s pocket—most famously when “Good Times” (cut months later) underpinned “Rapper’s Delight.” C’est Chic itself seeded that approach: its bass tone and open‑hi‑hat accents are audible in early ‘80s boogie, ‘90s G‑funk, and contemporary house. Electronic acts from Daft Punk to Disclosure regularly cite Rodgers’ “chord‑fragments‑as‑hooks” method as their harmonic compass.

Beyond technique, the album codified an R&B fashion ethos—elegant yet streetwise—that resurfaces whenever artists pair tuxedos with sneakers. Studio 54 lore often reduces the record to a glitter ball, but its true contribution is telegraphing that Black dance music can be luxurious and mechanically precise without contradiction.

Here, My Dear, Marvin Gaye

Cut under the weight of a divorce decree that handed royalties to an ex‑spouse, this double album should have been perfunctory. Instead, Gaye turned it into a soul opera of wounded falsettos, reggae detours, and conversational monologues that dare the listener to eavesdrop. The project trades the sociopolitical sweep of What’s Going On for forensic self‑analysis—horn charts curl around whispered admissions, and the rhythm section often drops away to leave Gaye nearly a cappella, as if confessing in real time.

The album’s later rediscovery reshaped R&B’s emotional playbook. Neo‑soul architects heard permission to be messy and deeply personal; one can trace the confessional lineage directly to Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite and even to Usher’s “Papers,” both of which echo Gaye’s willingness to map private turmoil onto groove‑centric canvases. Legal scholars still cite the record when discussing art created under court order, underscoring its singular position at the intersection of law and soul. Most important, Here, My Dear reframed vulnerability as strength within male R&B narratives. When contemporary singers bare unresolved hurt over live drums and Rhodes chords, they’re following a path Gaye bulldozed through his own heartbreak.

Bobby Caldwell (a.k.a. What You Won’t Do for Love), Bobby Caldwell

From its muted‑horn intro to the serpentine Fender Rhodes finale, this debut radiates nocturnal sophistication. Caldwell’s tenor slides between jazz phrasing and soul melisma, crafting an album that feels equally at home on quiet‑storm playlists and fusion‑club turntables. His label famously hid his face on early pressings, proving how seamlessly the music traversed R&B gatekeepers’ expectations around race. “What You Won’t Do for Love” became a standard, but the LP’s deeper cuts—“My Flame,” “Down for the Third Time”—are harmonic playgrounds for crate‑digging producers. 2Pac looped the title track for “Do for Love”; J Dilla, Common, and others mined Caldwell’s chord voicings for warm‑weather grooves, demonstrating how blue‑eyed soul chords could anchor hip‑hop’s emotional range.

Caldwell’s diction and songwriting bridged Steely Dan’s jazz‑pop with Philly soul’s warmth, paving a lane later cruised by Robin Thicke and Charlie Puth. Any time contemporary R&B melds complex chord progressions with breezy hooks, the album’s DNA flickers in the background.

Step II, Sylvester

Where Donna Summer had already fused gospel exaltation with synthesizer pulses, Sylvester took the synthesis further—literally. Recruiting electronic wizard Patrick Cowley, he layered high‑voltage synth stabs over churchy handclaps, birthing a prototype for the hi‑NRG sound that would dominate early‑’80s clubland. “Dance (Disco Heat)” and “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” stretch voice and machine until they blur, a daring statement from an openly gay, Black falsetto powerhouse in a hostile mainstream.

The impact is audible wherever dance music meets R&B. House producers revere the track’s octave‑leaping bass as a blueprint; LGBTQ+ pride parades still treat the chorus as a communal hymn. Reissues, remixes, and bio‑docs keep the album circulating, but its true immortality lies in how it frames queerness not as subtext but center stage, years before pop culture caught up. Moreover, Step II pushed live performance aesthetics: Sylvester’s sequined robes and gender‑fluid presentation foreshadow today’s boundary‑pushing stagecraft from Janelle Monáe to Lil Nas X. The album remains a reminder that R&B’s future is often written by those courageous enough to sing their full selves into the mix.

Essential Projects in 1978

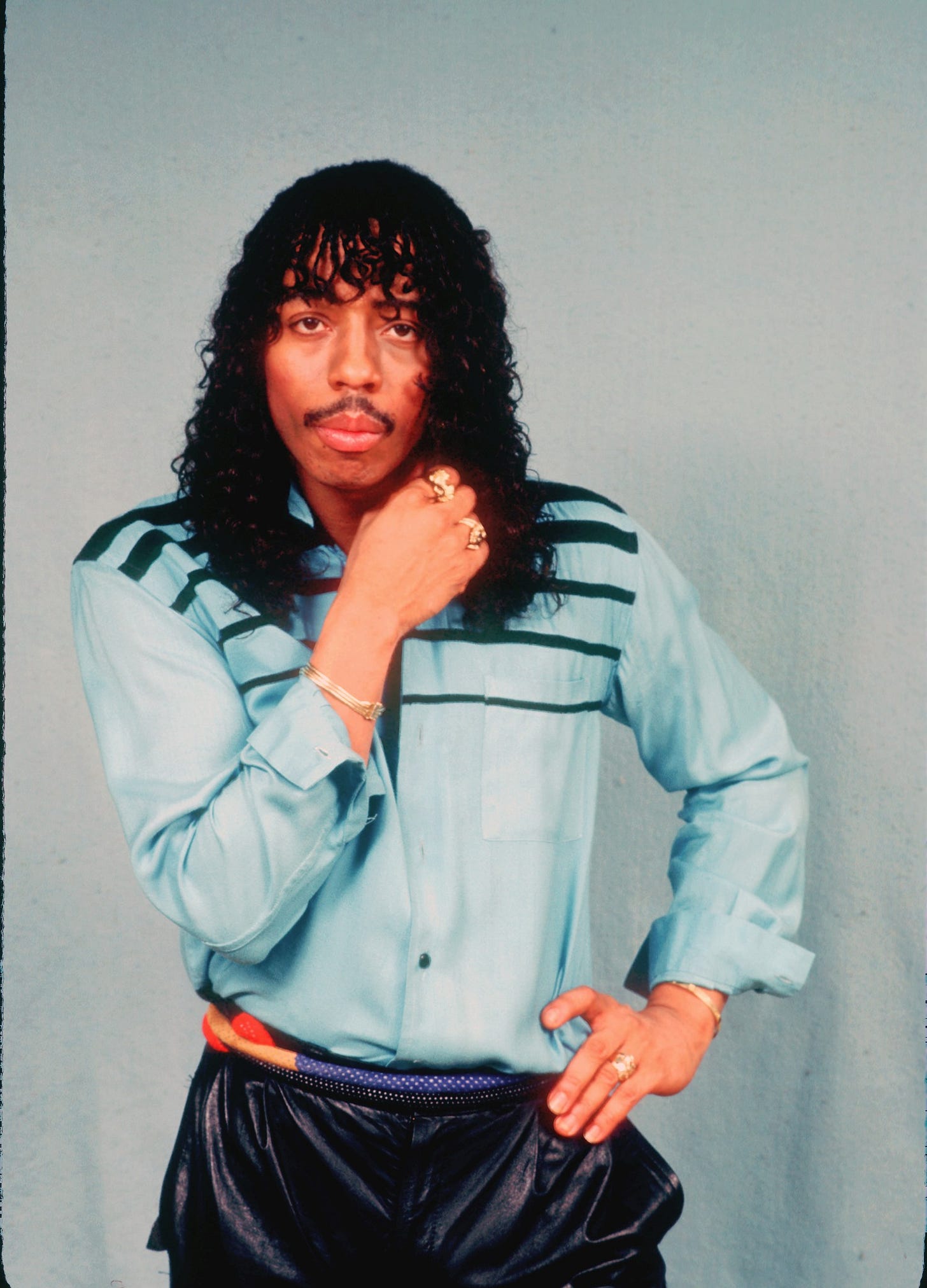

Come Get It!, Rick James

James detonated a new strain of funk the moment the clavinet hook of “You and I” hit R&B radio. His self‑coined “punk‑funk” grafted raw rock guitar distortion and street‑corner call‑and‑response onto Motown’s horn‑rich lineage, announcing that the label’s glory days could morph rather than fade. The album’s elastic bass‑lines and phased‑out synths forecast the West‑Coast G‑funk palette a decade early, and its recreational‑herb paean “Mary Jane” became a reference point for every rap act that sampled or name‑checked it—from Redman to A$AP Rocky. In an era when disco’s glitz threatened to eclipse gritty groove, Come Get It! re‑centered the conversation around bottom‑heavy syncopation and outrageous personality, ensuring funk stayed a core building block of contemporary R&B.

Tasty, Patti LaBelle

Coming off the boundary‑pushing trio Labelle, Patti’s second solo LP delivered a stylistic buffet that married New Orleans gospel muscle to Studio 54 propulsion. “Eyes in the Back of My Head” lit up disco floors with conga‑driven breaks, but deep cuts such as the Boz Scaggs–penned “You Make It Hard to Say No” showcased husky phrasings that later power‑balladeers would echo. The record also marked LaBelle’s emergence as a writer—she co‑scripted “Teach Me Tonight,” telegraphing the personal authorship that would define ’80s R&B divas. By sliding between club, cabaret, and choir without losing coherence, Tasty proved a solo artist could traverse multiple Black‑music traditions on one platter and pointed the way for eclectic statements by everyone from Whitney Houston to Jazmine Sullivan.

For You, Prince

At barely 19, Prince produced, arranged, and played every instrument, laying the blueprint for total studio autonomy. Multitracked falsettos on “Soft and Wet” hinted at the sex‑positive hymns to come, while the layered Oberheim synth‑horns forged an icy sparkle that would soon be dubbed the “Minneapolis sound.” The obsessive overdubbing (46 vocal lines on the opener alone) became a case study for DIY auteurs, inspiring everyone from Teddy Riley to The‑Dream to treat the control room as personal playground. Though modest on arrival, the album’s one‑man‑band ethos permanently expanded expectations of what a Black pop debut could look like: genre‑fluid, technology‑driven, and fiercely self‑determined.

Raydio, Raydio

Ray Parker Jr. flipped his reputation as session ace into songwriter‑producer‑bandleader glory. “Jack and Jill” fused nursery‑rhyme narrative to a rubbery funk groove, giving DJs a mid‑tempo breather between high‑octane disco cuts and prefiguring the story‑song trend that Michael Jackson and Stevie Wonder would mainstream. Elsewhere, guitar‑talk‑box flourishes from Wah‑Wah Watson blurred boundaries between R&B and yacht‑rock, setting a template for polished, radio‑friendly soul that the ’80s Quiet Storm era leaned on heavily. The album’s slick engineering and gleaming chords revealed how studio finesse could coexist with propulsive rhythm, influencing producers who chased crossover without sacrificing groove.

Chaka, Chaka Khan

A solo bow that exploded with “I’m Every Woman,” an Ashford & Simpson masterclass in key changes, stacked harmonies, and feminist firepower. Arif Mardin’s arrangements wrapped Khan’s athletic alto in strings and Rhodes, showcasing how disco‑ready orchestration could elevate, rather than eclipse, an R&B vocal performance. The record became an instant songbook for club DJs and live bands, while its lyrical assertion of multifaceted womanhood fed directly into later empowerment anthems by Mary J. Blige and Beyoncé. Musically, the way “Love Has Fallen on Me” spliced modal jazz chords into a four‑on‑the‑floor pulse foreshadowed neo‑soul’s harmonic adventurousness.

Love Tracks, Gloria Gaynor

Recorded while Gaynor wore a back brace after spinal surgery, the album’s sleeper B‑side “I Will Survive” emerged as a universal anthem of resilience. Its gospel‑soaked declaration over disco strings turned breakup catharsis into collective empowerment, later enshrined by the Library of Congress as culturally significant. DJs relished the track’s intro‑less groove and key‑change climax, standardizing a tension‑and‑release formula that permeated house and Hi‑NRG. Beyond club life, the song’s embrace by LGBTQ+ communities and survivors of domestic abuse signposted R&B’s capacity for social solidarity, cementing Love Tracks as a milestone where dancefloor ecstasy met lived experience.

Cheryl Lynn, Cheryl Lynn

A gospel belter fresh from The Gong Show jammed with Toto’s David Paich and a cadre of L.A. studio killers to craft a record equal parts church and roller‑rink. Opener “Got to Be Real” cracked the code for brass‑driven disco‑funk, later sampled on Father MC’s “I’ll Do 4 U,” embedded in Ultimate Breaks & Beats, and interpolated by Mariah Carey—proof of its sample‑ready chord stabs and open drum break. Deeper cuts like “Star Love” stretched vamp‑based arrangements to six‑minute workouts, offering a template for extended 12‑inch mixes. The album’s musicianship signaled a new level of instrumental slickness that would dominate early‑’80s boogie, making it required study for session players and producers chasing dance‑floor immediacy with jazz sophistication.

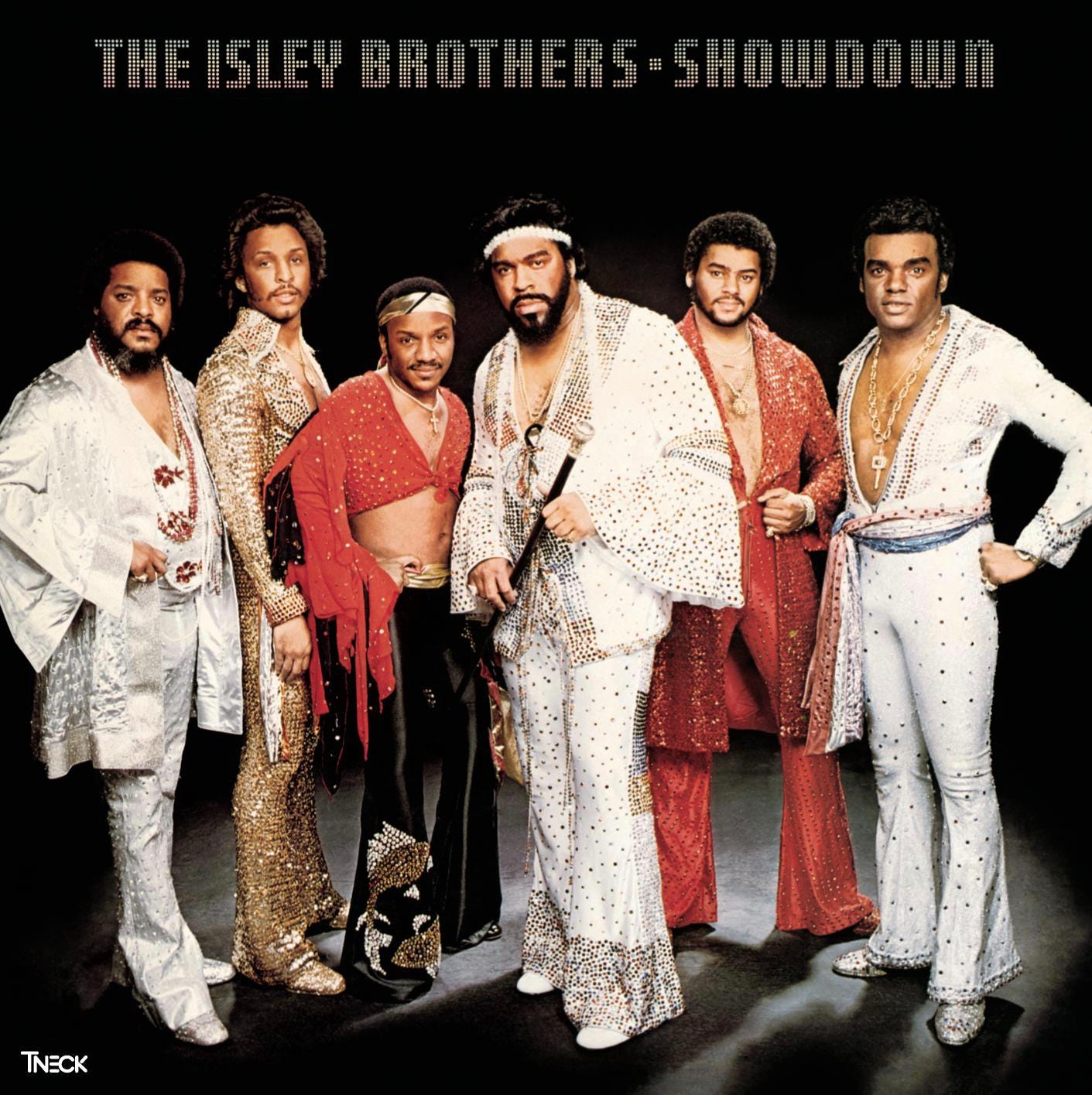

Showdown, The Isley Brothers

The 3 + 3 lineup—three singing elders, three instrument‑slinging younger siblings—hit maximum synergy here. Lead single “Take Me to the Next Phase” masqueraded as a stadium recording but was a studio concoction loaded with crowd overdubs, pioneering the “fake live” aesthetic later used by Maze and Cameo. Synth‑clavinet interplay and Ernie Isley’s fuzz guitar bridged hard funk and arena rock, while ballad “Groove With You” laid groundwork for the Quiet Storm format. The record demonstrated that a veteran act could self‑produce cutting‑edge funk, influencing generations of family‑run ensembles from DeBarge to Hanson.

A Taste of Honey, A Taste of Honey

Fronted by bassist‑vocalist Janice‑Marie Johnson and guitarist Hazel Payne, the quartet smashed gender norms with “Boogie Oogie Oogie,” whose slap‑bass intro became mandatory listening for funk hopefuls. The album’s Mizell‑brothers production layered silky string pads over syncopated wah‑wah guitar, illustrating that women instrumentalists could command both groove and spotlight. Its success opened doors for female‑led funk outfits (Klymaxx, Mary Jane Girls) and its crossover appeal showed labels that disco‑funk hybrids could dominate multiple charts simultaneously. The track’s break lived on in hip‑hop as a go‑to party sampler, cementing the LP’s cross‑generational currency.

Pinnacle Singers/Groups of 1978

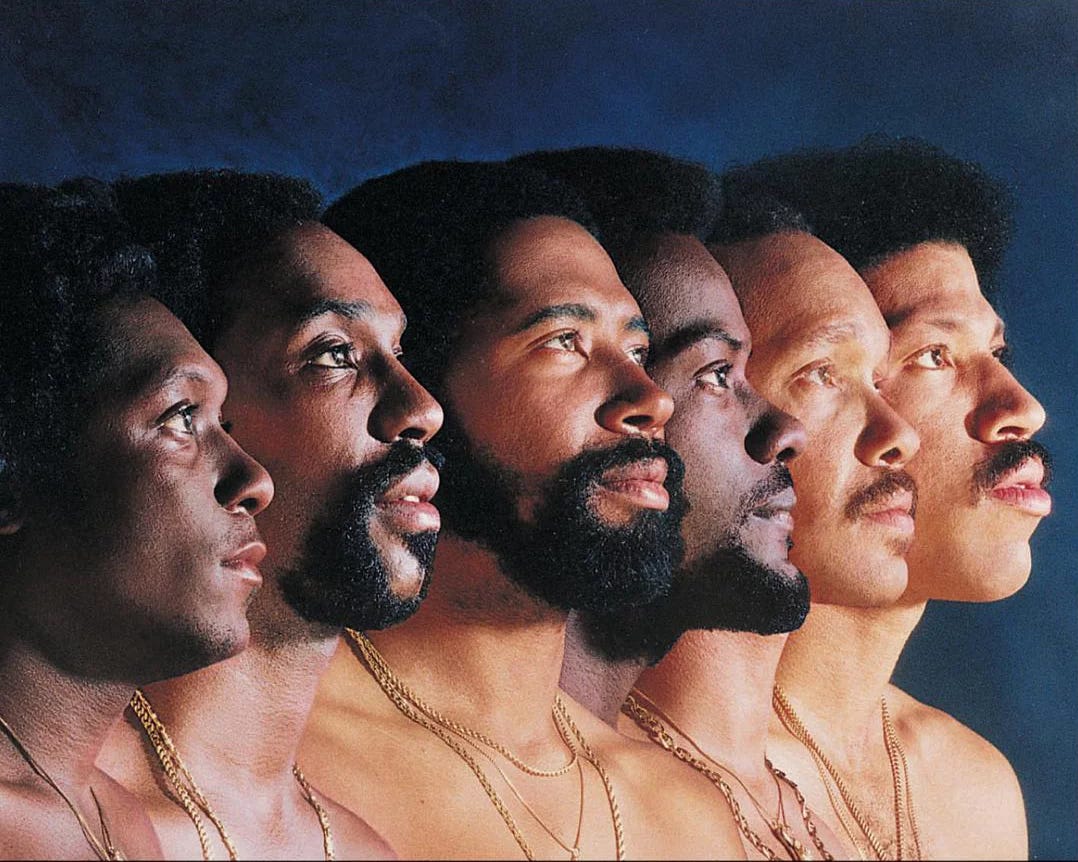

Earth, Wind & Fire

By the time the calendar flipped to ‘78, Maurice White’s super‑band was already a touring juggernaut, but “September” was the moment they cemented total pop‑soul hegemony. The single shot to No. 1 on the Hot Soul chart and crashed the pop Top 10, all while being tacked onto a Greatest Hits package—proof they could move new units without even cutting a full new LP. Stadium shows, a horn‑driven revue few could rival, and that impossibly buoyant groove kept them at the absolute peak of the R&B pyramid.

Donna Summer

Disco’s queen spent 1978 doing something no other R&B‑leaning artist managed that year: simultaneously topping the Hot 100 and the Billboard 200. On the chart week of Nov. 11, 1978, she held the No. 1 single (“MacArthur Park”) and No. 1 album (Live and More), following a summer where “Last Dance” (released Jul. 2, 1978) bagged her first Grammy. It was the pure definition of apex status—awards season validation, double‑platinum sales, and club ubiquity all colliding at once.

The Commodores

Lionel Richie was still in‑band, and Natural High proved the group could balance arena‑funk with Lionel’s emerging pop‑ballad instincts. “Three Times a Lady” went No. 1 on the pop and R&B charts, while the album itself ruled the R&B LP chart for eight weeks. Commercial saturation plus a monster crossover slow jam put the Tuskegee crew at their commercial summit.

Breakout Stars in 1978

Rick James

Come Get It! dropped, and the lead single “You and I” lit the fuse on his self‑branded “punk‑funk.” The gold plaque came fast, Motown suddenly had a new rogue superstar, and radio programmers realised they had to leave space between ballads for leather‑clad, synth‑bass‑driven anthems. A debut that instantly redrew the funk playbook.

Chic

Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards had chart pedigree already. However, “Le Freak” was the explosion that took them from hip producers to headline‑stealing artists. The single was a smash hit on the Hot 100 and R&B charts, sold millions, and fired C’est Chic into the mainstream. In one fell swoop, Chic turned the rhythm‑guitar scratch and octave‑leaping bass line into lingua franca for every band chasing a dance‑floor hit.

Cheryl Lynn

A total unknown until Columbia slipped “Got to Be Real” to DJs in August 1978. By year’s end, the single had reached No. 1 on the soul chart and cracked the pop Top 20, powered by Lynn’s gospel‑honed belt and Ray Parker Jr.’s slinky guitar. One song—and a self‑titled debut LP—was enough to earmark her as the next vocal powerhouse the majors would bank on.