September 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from Lady Wray to anaiis, here are notable releases in September that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

September 2025 arrived with the kind of restless energy that makes you pay closer attention. Genres bent and reshaped, veterans tested their boundaries, and newcomers found themselves with something to prove. Across R&B, rap, pop, and jazz, the month’s releases demonstrated how personal risk and careful craft can intersect, transforming familiar forms into fresh statements. These projects didn’t settle for routine; they embraced tension, leaned into vulnerability, and reached for spectacle without losing intimacy.

What follows is a collection that reflects that richness—records that shine in their own corners yet speak to each other in unexpected ways. You’ll find artists opening up about private struggles, others reinventing themselves on grand stages, and some pushing underground aesthetics into sharper focus. It’s not a month defined by one trend or sound, but by a refusal to coast. The best albums of September 2025 carry weight, offer joy, spark debate, and remind us why attentive listening still matters.

Olivia Dean, The Art of Loving

If you know about Olivia Dean, then you understand how quickly she’s grown. She pairs that familiar palette with diaristic songwriting as shown on Messy, but she deals with the mundane joys of new romance and the awkwardness of moving on from old love, her sweet, understated voice free of the crooner affectations that weigh down so much contemporary pop on The Art of Loving. On “Loud,” she lets her full voice soar over strings and a guitar melody reminiscent of Amy Winehouse and Adele, while “Close Up” turns intimacy into a whispered confession, accompanied by piano and horns. “A Couple Minutes” samples a 1971 guitar riff from Hot Chocolate and uses its groove to underscore the warmth of new love. “Baby Steps” embraces self‑love after a breakup, as Dean sings about being her own safe harbour and planting roses to celebrate her growth. The introductory title track frames the album as an exploration of what it means to care and be cared for, and “I’ve Seen It” promises that love is all around, concluding that it has been inside her all along, utilizing influences and writing with more detail and vulnerability. — Charlotte Rochel

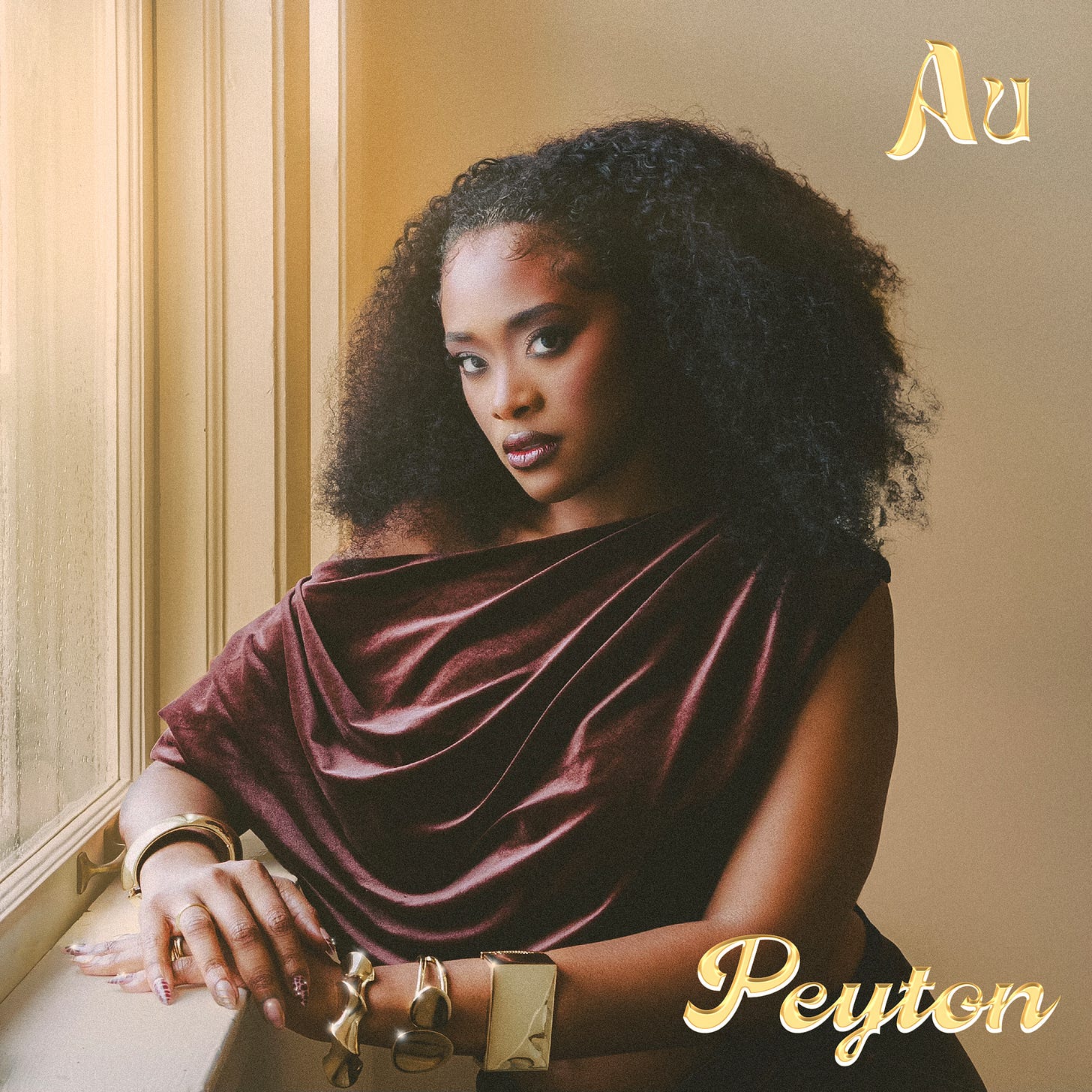

Peyton, Au

Peyton arrived in the mid-2010s with a flair for dreamy alt-soul; she began releasing full-length projects while still in her early twenties, yet often spoke about feeling constrained by the expectations of youth. Her sophomore album Au arrives after a four‑year stretch that included PSA and scattered collaborations, and she describes it as the moment she let go of self‑consciousness and fully embraced who she is as an artist. She worked closely with Shafiq Husayn and Om’Mas Keith, members of the LA collective Sa‑Ra Creative Partners, and credits them with creating a space in which she could take risks and blend lo‑fi textures with psychedelic funk. She’s wrestling with betrayal, confusion, and disappointment, yet the mood never turns sour—Au is a kind of pact with the self: even when the world tries to dull your shine, you stay luminous. Her second LP leans into spacious R&B, moments of slow burn, and dreamy instrumental touches, with guest features (Didda Joe, Brian Alexander Morgan) adding color but never distracting from Peyton’s core tone. Peyton has painted a portrait of an artist who has grown comfortable enough with herself to let her guard down and let the songs breathe. — Jill Wanassa

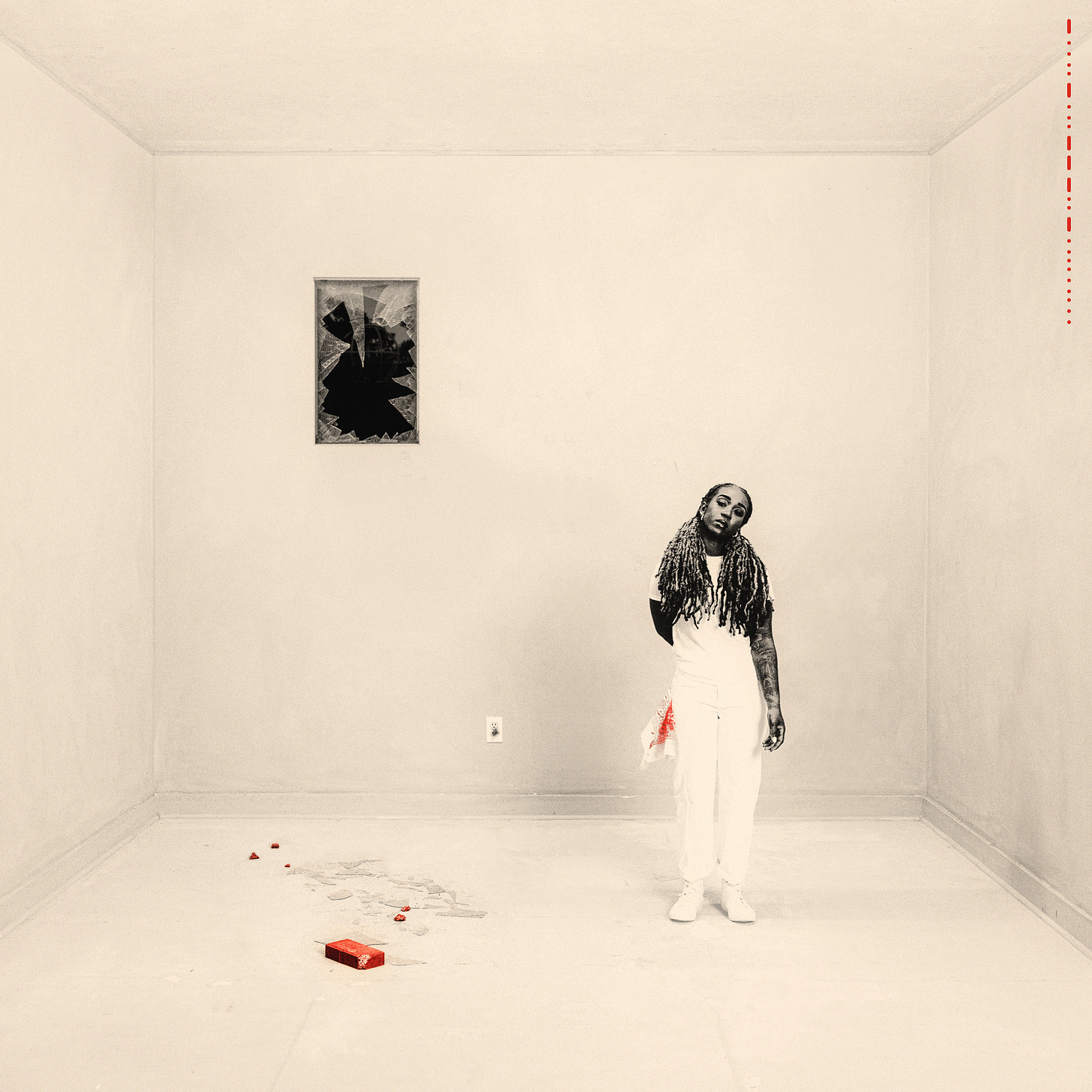

Jackie Hill Perry, Blameless

Jackie Hill Perry returned to hip‑hop after nearly a seven‑year hiatus, bringing with her the perspective of an author, spoken‑word poet, and mother. With Blameless, she built a conceptual “house” where each song occupies a room and together they form an examination of faith, the Church, and personal accountability. “The Home” invites us into that house by narrating a scene at a red house with a cracked window, knocks on the door, slips inside and wanders through rooms where greed and distraction lurk, and “Pride and Prejudice” she confronts her identity head‑on—“Indian in my blood/You can tell by the roots/Ain’t selling dream catchers/Everybody wanna be a prophet/‘Til it’s time tell the truth”—before the hook admits “Maybe I’m just relevant/Maybe I’m just arrogant/Maybe y’all need a therapist,” showing self‑examination and vulnerability. “I Ain’t Worried” finds her telling anyone who will listen that she doesn’t chase money or gossip, boasting, “Got four babies and they crazy call me Donda,” and dismissing online critics by saying, “Why you talking mess? It ain’t no flex to spin that gossip/When I spit that gospel.” Even the uplifting “Keep Your Head Up” carries depth; over bright keys, she urges weary women to look to heaven, reminding them that they are seated in heavenly places while cautioning against overthinking and self‑sabotage. Throughout Blameless, Perry knits theological reflection into conversational rhymes, blending admonition with encouragement to craft a record that feels like both a candid journal entry and a sermon in equal measure. — Murffey Zavier

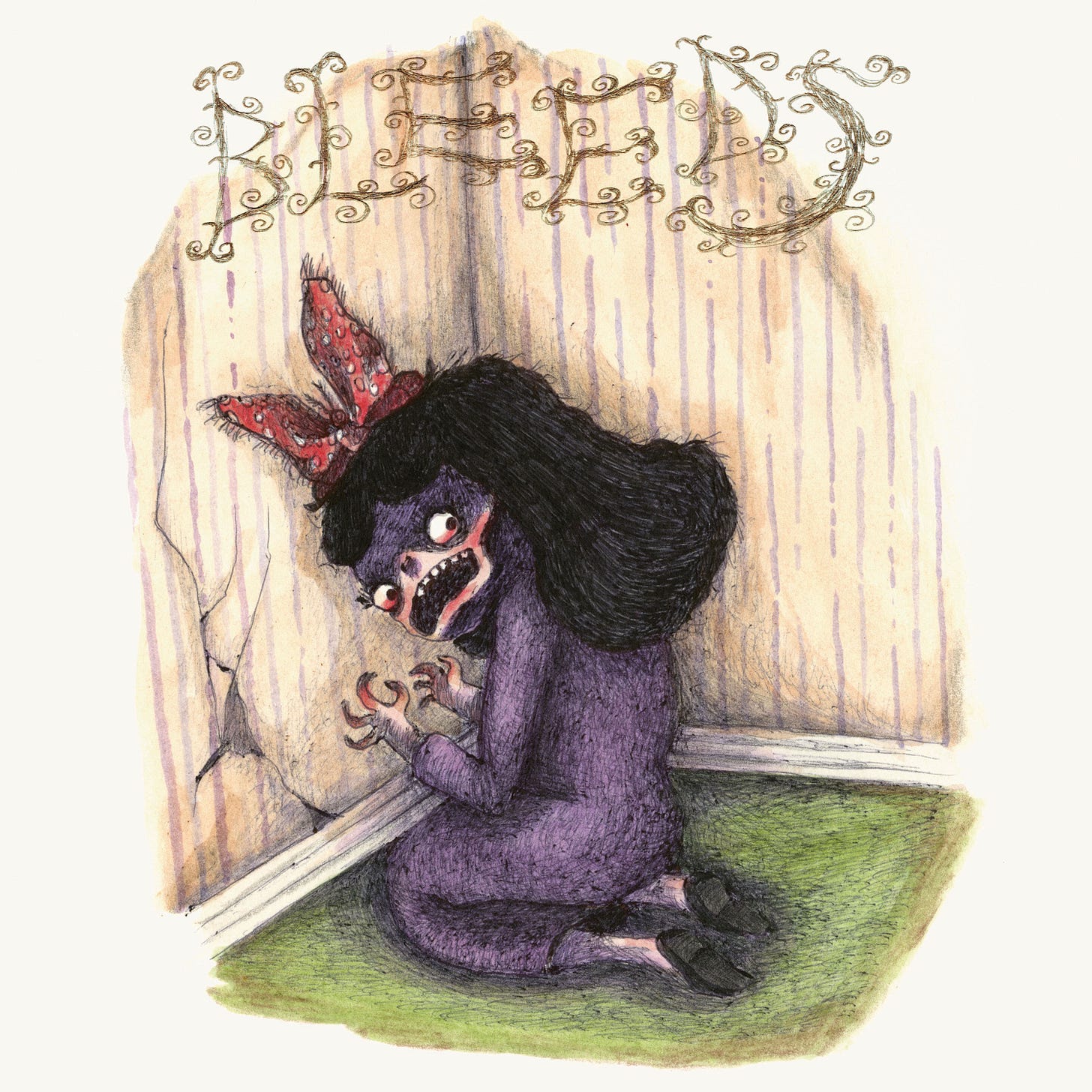

Wednesday, Bleeds

After Rat Saw God, which turned Wednesday into defining voices in what some call “countrygaze,” this new album carries the fractures that emerged behind the scenes—Karly Hartzman and MJ Lenderman parted ways romantically in 2024, yet the writing for Bleeds spans before and into that rupture, so the record holds both hindsight and unknowing. The songs paint heartbreak as betrayal, longing, resentment, moments of self-accusation, and moments of surrender. Hartzman frames landscapes of small-town violence (both physical and emotional), of characters who hurt and are hurt, of loss both intimate and communal; she makes space for rage and exhaustion, and she refuses simplification. What develops isn’t just sadness but the strange beauty of scars. Instrumentation is tense and wild. One evening, I found myself in “Carolina Murder Suicide,” tracking how a true crime tale becomes a metaphor for relational combustion; in “Bitter Everyday,” what sounded like anger transforms into recognition. Here, Wednesday’s most precise mapping yet of how to write into pain without losing your foundation. It follows that this album is not only their most explicit artistic statement to date, but potentially the one that will last. — Oliver I. Martin

Joanne Robertson, Blurrr

Joanne Robertson has balanced songwriting and visual art since her early days collaborating with Dean Blunt. Robertson’s high, fragile vocals blur words into shapes, making lyrics feel like half‑remembered conversations; on one song, she sings about a “mystery gone” then whispers a plea to take it with you, letting the silence after the line hang heavy. On Blurrr, she combines those disciplines, treating her guitar and voice like paintbrushes. The record was written between oil‑painting sessions and raising her toddler, and that domestic reality informs its tone. Her fingerpicked guitar motifs circle like waves, and she often treats chords the way Mark Rothko treated color—subtle shifts change the entire mood. In the opening track, she notes that her songs are like journeys; she compares the experience to walking alone at night, glimpsing lights in the distance. On “Exit Vendor,” bright chords hide a voice that sounds broken, and she toys with the idea that happiness and heartbreak can coexist. A later song finds her repeating a phrase about lending fate, turning the line into a mantra about sharing burdens. With blurring lyrics and stretching time, Robertson invites us to sit with the small moments that add up to meaning. — Charlotte Rochel

Iman Europe & Kaelin Ellis, Chrysalis

Having moved between rap and R&B since the mixtape Caterpillar, Iman Europe arrives here from limbo, from that in-between space where the self is being stretched by time and observation, and gives Chrysalis as both a confession and an emergence. Growth is the album’s architecture. Europe sheds old skins, stepping out of social media masks, growing wings in private while being watched in public. She digs into transformation in digital era terms—comparison, performance, solitude—and the title track opens with surrender, retreat, longing to evolve unseen; elsewhere, desire for authenticity pulses under layers of expectation. There’s tension between showing up and pulling back, between craving visibility and resigning to its exhaustion, and that tension becomes the album’s emotional backbone. The production by Kaelin Ellis tends toward atmospheric introspection, with soft synth washes, warm drum pulses, and harmonies that cradle rather than crowd. There are moments of R&B warmth, moments when she leans into grooves that could be lounge-room slow burners. Chrysalis continues Europe’s through-line of metamorphosis—and in a moment when many artists attempt vulnerability as image, she lets it be both struggle and liberation, confessional but composed. It feels like a long-awaited reemergence rather than a debut record for those who know what it is to feel both cocooned and ready to fly. — Ameenah Laquita

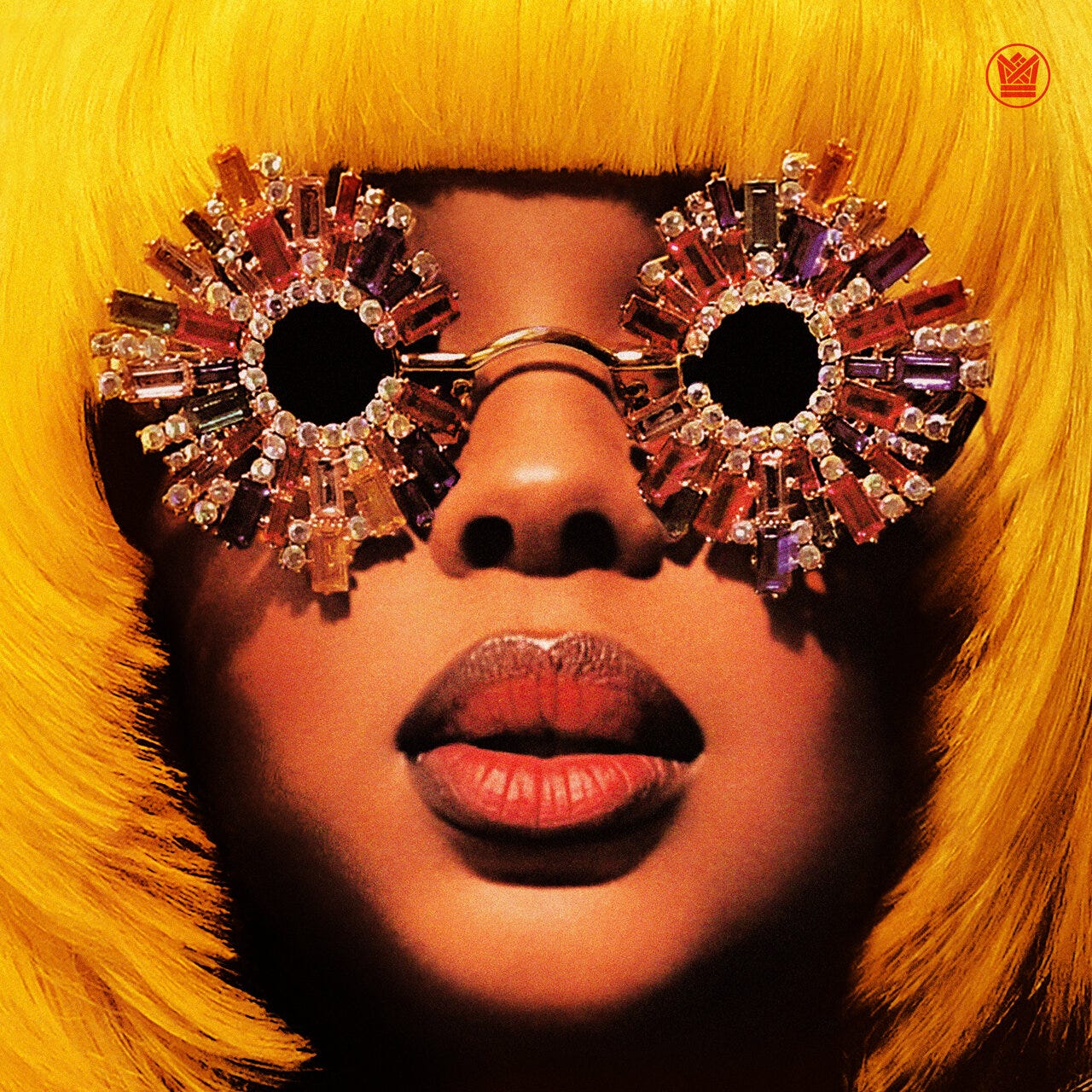

Lady Wray, Cover Girl

Lady Wray has since built a catalogue steeped in church harmonies and old‑school rhythm‑and‑blues. Cover Girl finds her easing into that role with confidence. After the introspective Piece of Me, this record is more playful and uplifting, blending 60s soul, 70s disco, 90s hip-hop, and gospel influences into one celebratory mix. The organ‑driven “My Best Step” uses hand‑claps and church keys to reaffirm loyalty and perseverance, and the album’s messages of empowerment are apparent in songs such as “Where Could I Be” and “Hard Times,” which invoke faith and resolve amid hardship. The title track revisits a childhood nickname as Wray sings about losing herself to please others and the slow process of rediscovering her own beauty. Throughout the album, she reminds women that they are worth more than society tells them, as on the retro‑soul groove “Higher,” and she ends with “Calm,” a gospel‑tinged prayer that casts burdens aside and looks toward brighter days. Lady Wray delivers an album that balances upbeat anthems with honest reflections on love and self-acceptance, drawing from her church roots and decades of experience. — Imani Raven

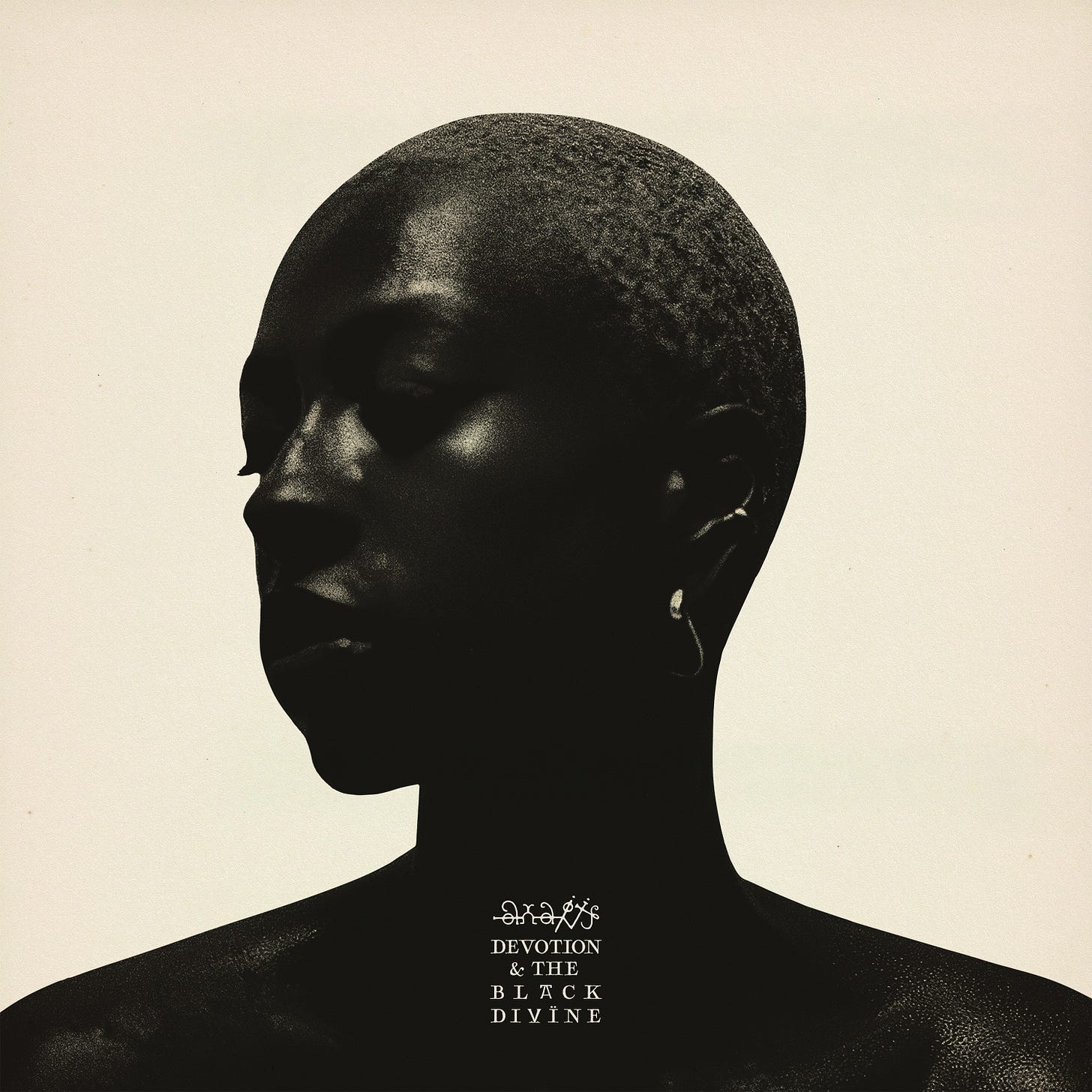

anaiis, Devotion & the Black Divine

anaiis writes from what she calls a collective consciousness, letting the album serve as a conversation between herself and the world. Recorded live to tape at London’s 5dB Studios, Devotion & the Black Divine grew out of her experiences as a new mother and her search for acceptance. The songs lean into uncertainty and grace, capturing the messiness of being human while holding on to a still center. On “Moonlight,” she sings gently over swirling chords, contemplating how hope can persist in darkness. The slow, sensual single “Deus Deus” heralded the record with its sultry soul reggae groove, hinting at the album’s spiritual core; its repeated gratitude expresses a personal prayer without ever becoming didactic. She moves between spoken‑word cadences and melismatic runs, reflecting on the weight of motherhood and the freedom that comes from surrendering control. Although the arrangements shift from sparse ballads to experimental R&B, the through‑line is her willingness to place every emotion at the core. — Ameenah Laquita

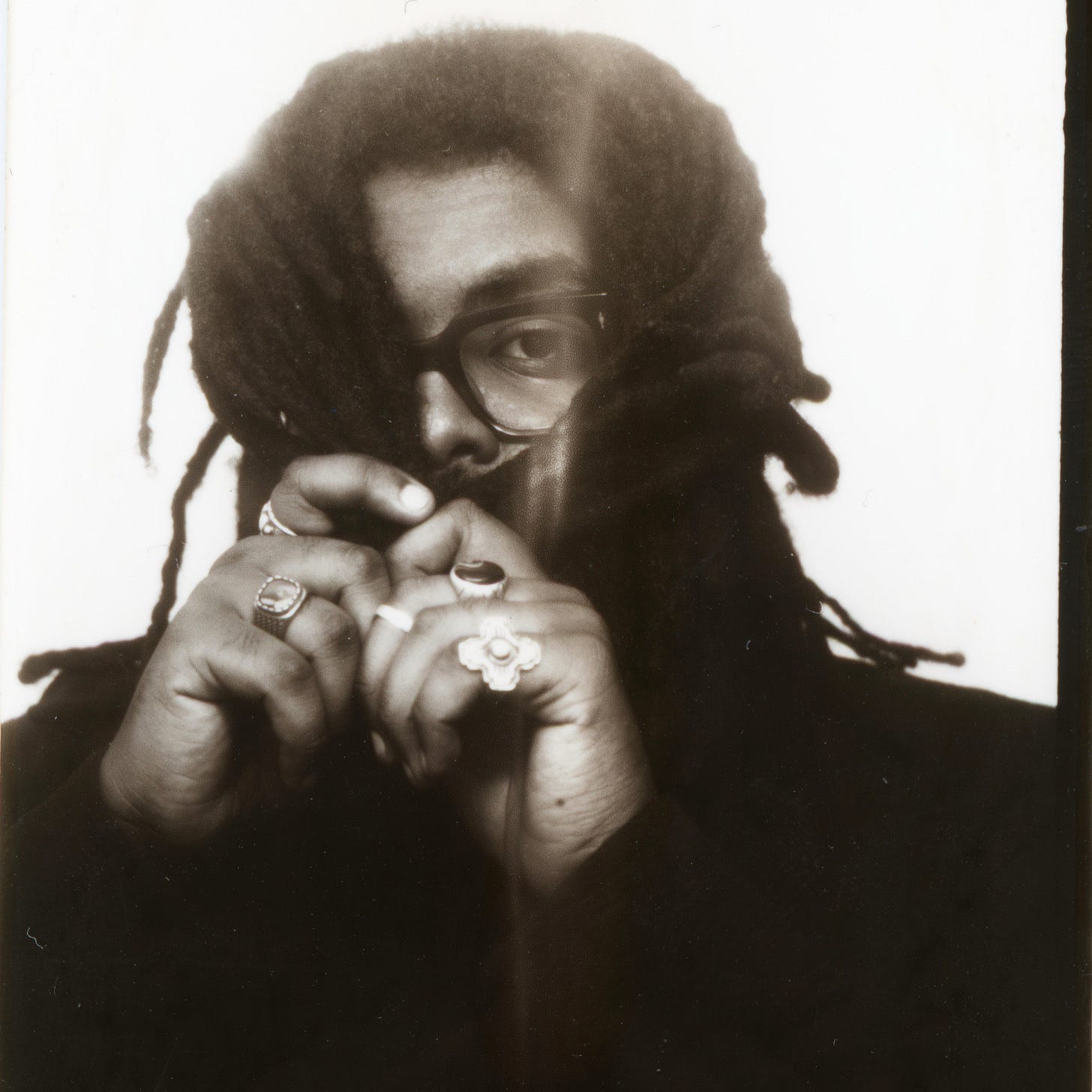

Kojey Radical, Don’t Look Down

Having made a splash with Reason to Smile, Kojey Radical now takes more inward turns; this follow-up is less about gloss, more about fissures. He began with reflections: spoken-word prologues, reckoning with grief (“How many homies didn’t make it?”), parenthood, identity, public image. He’s still the poet-rapper, but here the narration is more continuous, more panoramic. If you’re a fan of Radical, you know he leans into sample-rich textures, jazz inflections, symphonic soul touches—songs aren’t just beats plus verse but atmospheres you step into. There aren’t obvious radio hits, but each track feels necessary, revealing parts of the emotional scaffold, with pressure, doubt, and the longing for honesty. This breadth is evident in the music (featuring Ghetts, Bawo, MNEK, Dende, and James Vickery), which draws on golden-age hip-hop, disco, grime, indie, jazz, and ska to create a shifting sonic landscape. In interviews, he explains that he wants to be transparent about his flaws so fans can trust him, as he struggles with pride, pressure, ambition, and exhaustion. Within UK rap/progressive hip-hop, Don’t Look Down stakes a claim for patience: for letting songs marinate; for letting any music fan slow down and sit with discomfort. It’s one of those albums that rewards absorption, repeated plays, and is perhaps one of his strongest works yet. — Randy

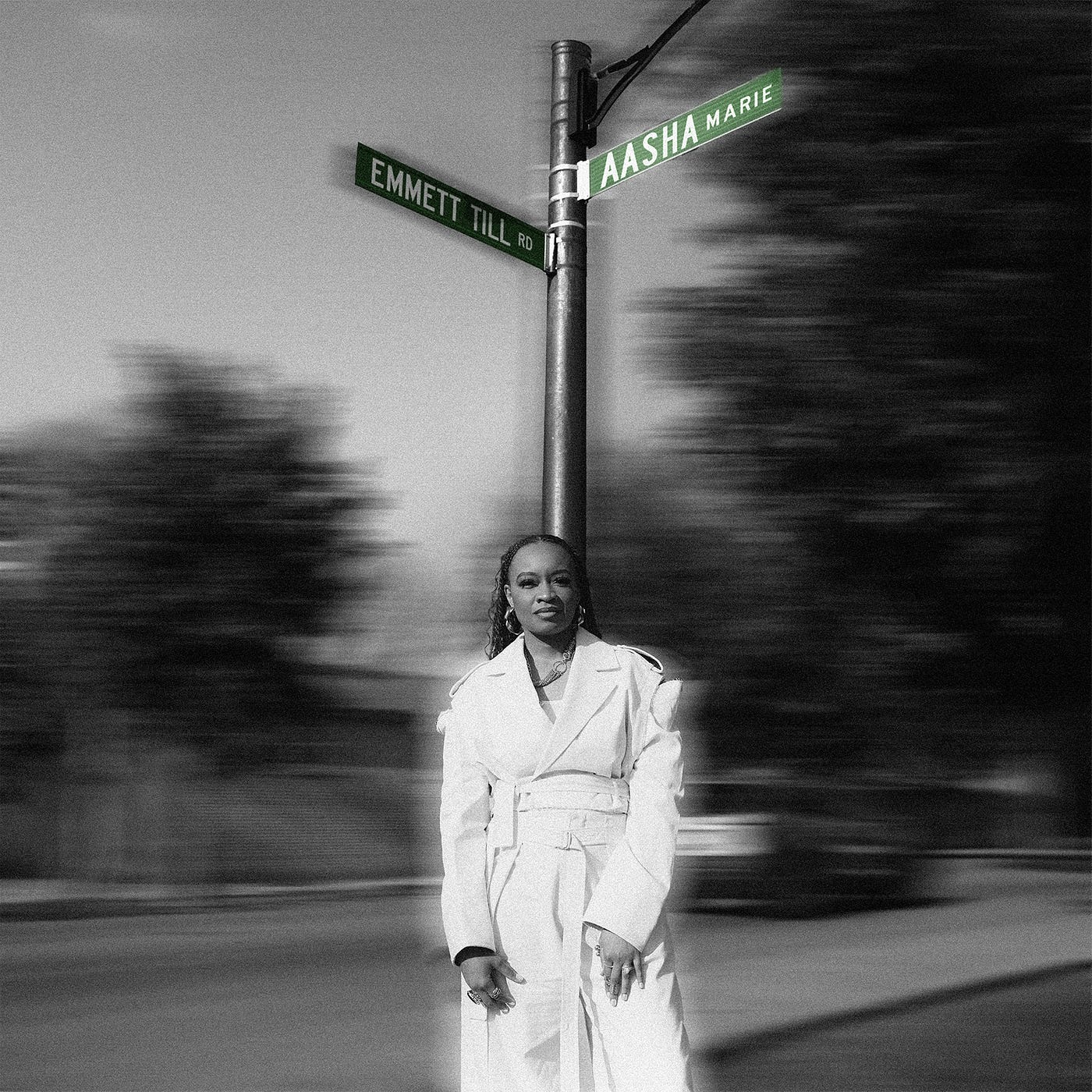

Aasha Marie, Emmett Till Road

Where some artists use debut albums as calling cards, Aasha Marie has written hers as a saga. Emmett Till Road is sprawling by design, a double-disc project that carries twenty-seven songs without apology, each one another stone on the path she’s charting between South Florida upbringing, Chicago grounding, and the spiritual inheritance of Black American history. By invoking Emmett Till, she makes it clear from the start that her music will carry generational weight: this is not just her autobiography, but an offering to the collective memory of those who did not live to tell their own stories. Marie alternates between urgency and meditation—portraits of friends lost, neighborhoods scarred, and romances that flare amid the fire. Church imagery filters through repeatedly, a reminder of the faith she wrestles with and still clings to; it’s not decoration but the backbone of her storytelling. The record ranges from classic boom-bap loops, blues-inflected guitar, gospel-tinged piano, and crisp contemporary drum patterns, which firmly root it in the present. This ensures that the length feels purposeful (like a full-length film), mixing in interludes that bind the narrative and keep us entertained. Emmett Till Road functions as a torch, an album that affirms Aasha Marie’s commitment to using her art as an archive, a form of resistance, and an invitation. As lengthy as it is, she has chosen to stretch her canvas, and it’s something demanding but advantageous, a document you live with rather than skim. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Gary Bartz & NTU: The Eternal Tenure of Sound: Damage Control

Gary Bartz has been a standard‑bearer in jazz since his days with Art Blakey, and he has spent his eighties demonstrating that experimentation doesn’t stop with age. After a dozen years away from the studio, he returned by cashing out his retirement savings and taking a sabbatical from his teaching post to fund the first instalment of a trilogy. Recorded at the North Hollywood home studio of his godson and producer Om’Mas Keith, the album sees the NEA Jazz Master, now in his mid‑80s, assemble a cross‑generational band featuring pianist Barney McCall, drummer Kassa Overall, and guests such as Kamasi Washington, Terrace Martin, Nile Rodgers, and Theo Croker. He reimagines R&B and soul tunes that he often sings in the shower, including Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Fantasy,” Curtis Mayfield’s “The Makings of You,” Midnight Star’s “Slow Jam,” and DeBarge’s “Love Me in a Special Way.” Each cover is a springboard for improvisation rather than a faithful reprise: “Fantasy” opens with shimmering keyboards and harp while Bartz’s alto sax dances around a melody before he shares a gentle vocal refrain with Rita Satch. “One Hundred Ways,” associated with Quincy Jones, grooves as guitars weave counter‑lines around his searching phrases, and in a tribute to his mentor McCoy Tyner, he turns “In Search of My Heart/Love Surrounds Us Everywhere” into a ten‑minute funk workout where horns trade solos over a churning rhythm section. Bartz uses it as an opportunity to connect with a younger generation of musicians and listeners, proving that an 84‑year‑old saxophonist can still find new stories inside old songs. — Nehemiah

Geese, Getting Killed

Brooklyn band Geese built their reputation on youthful experiments—first with the raw indie rock of Projector, then the psychedelic alt‑country of 3D Country—and frontman Cameron Winter even released a solo record. Getting Killed reflects that restless spirit. Recorded over a blistering ten‑day session with producer Kenny Beats, the record toggles between manic punk energy and moments of surprising tenderness. The opening song jolts listeners with careening guitars and a lyric about waking up on an island of men, hinting at the album’s fascination with masculinity and isolation. On the title track, Winter sings about violence like it’s an absurd joke, his deadpan delivery contrasting with the band’s convulsive groove. Songs often change direction mid‑section, whether it’s an off‑kilter funk riff dissolves into a free‑jazz breakdown, then snaps back into a tight rock hook. “Trinidad” builds from a twitchy guitar line into a shout‑along chorus that recalls high‑school punk shows, and then later on, “Bow Down” slows to a crawl as Winter croons about surrendering to forces bigger than himself. The most explicit statement comes on “Taxes,” where he confesses that he should “burn in hell” for dodging obligations; the track’s hallucinatory video features moshing and feels like an exorcism. Geese haven’t settled on a single style, and that refusal becomes the record’s strength. — Charlotte Rochel

Elmiene, Heat the Streets

The ambition and voice of Elmiene have been growing. Following a string of EPs that teased intimacy and promise, Heat the Streets delivers. It’s the story of love, loss, longing, and the pain of being unable to connect when distance or silence gets in the way. The project details his disorientation after a breakup, introducing the themes of vulnerability and longing that run throughout it. Rather than chasing fleeting trends, he highlights timeless values and moves from tender ballads to funk‑driven grooves. His gentle tenor and poetic lyrics transform each song into an intimate confession, and the interludes offer a welcome respite. There’s a confessional quality, wherein moments of heartbreak (“Useless (Without You)”) but also celebration (“Sunny”), a sense that vulnerability is your only weapon. A mixtape like this refuses to gloss over grief, which remains raw yet rich. When someone steps beyond hype and creates works you come back to for comfort or catharsis, Elmiene feels like the promise realized. — Jamila W.

Ayoni, ISOLA

Ayoni has always been the kind of artist who writes with the clarity of someone searching for her own reflection in real time. Building up her repertoire of loosies and featured on Noname’s Sundial, ISOLA is where that process transforms into a cohesive body of work. The title carries dual weight because it’s a nod to her Barbadian roots, an island identity that shapes her worldview, and it’s also an exploration of isolation, the way distance can magnify pain and foster transformation. She tells stories of heartbreak, anger, renewal, and self-discovery—songs that read like journal entries but are polished into resonant anthems. Tracks such as “It Is What It Is” and “Bitter in Love” walk directly into the grief of betrayal without posturing, while “Trace of Your Love” and “Vision” open the lens wider, asking what it means to hold on when love dissolves. She executive-produced the album herself, and that sense of authorship shows in the way motifs recur and melodies return as lessons. It’s a declaration of presence, proof that Ayoni’s pen and voice are strong enough to build universes without overstatement. It arrives as a debut that sounds like a marker planted in the ground, pointing toward even larger visions still to come. — Brandon O’Sullivan

James Vickery, JAMES.

Having built up through EPs and collaborations, James Vickery opens this album in a space without compromise—it’s earned through refusal to shrink. Everything from ballads that sting to funk-inflected pop that makes you want to move, and songs that sit somewhere in between, trying on moods, shedding them, finding something honest. Vickery does what he does well, writing about self-reflection, love in its best and worst forms, joy, and the burdens of feeling deeply. He draws from the warm textures of soul and funk, clean guitar lines, keys that slide in softly, rhythm that tugs without overwhelming, and vocal layering that yields richness. On “All In,” he plays with bravado in the verses before admitting in the chorus, “I’m all in, I’m not going anywhere,” a wholesome promise that softens the swagger. The track’s upbeat groove reflects his love of classic R&B and early 2000s pop, and it highlights his versatile falsetto. Even the sultry “Hotel Lobby,” set over a bossa‑nova rhythm, uses its steamy scenario to explore self‑acceptance and vulnerability rather than braggadocio. This isn’t music pretending it isn’t afraid or uncertain—instead, it’s a documentation of all that in real time. JAMES. is a continuation and an evolution, showing how far he’s come in forging a personal voice in UK R&B, arriving just when the genre needs another record that’s comforting and brave. — Imani Raven

Joy Crookes, Juniper

After her 2021 debut, Skin, earned her award nominations and viral success, South London artist Joy Crookes disappeared from the spotlight. Illness and mental health struggles delayed her follow‑up, and the four‑year gap looms large over her second album, Juniper. This record is steeped in exhaustion and defiance: on the opener “Brave,” she admits, “I’m so sick, I’m so tired, I can’t keep losing my mind,” and later in “Mathematics,” she bluntly confesses that she’s “pretty fucking miserable.” Rather than wallowing, Crookes uses these lines as entry points to songs about co-dependency, intergenerational trauma, and self-worth. “House With a Pool” examines abusive relationships with an unsentimental gaze, while “Carmen” skewers impossible beauty standards and ends with her still glowering resentfully at a so‑called perfect figure: “Why am I working double for just half of what you got?” Crookes sets these stories to a sonic palette that draws on retro-soul—electric pianos, warm bass lines, and Philadelphia-style strings—and infuses it with echoes of trip-hop and dub-reggae. The staccato piano riff in “Carmen” nods to Elton John’s “Bennie and the Jets,” and “Pass the Salt” is driven by a drum loop sampled from Serge Gainsbourg’s “Requiem pour un Con” and punctuated by a brief, explosive verse from Vince Staples. The arrangements mirror this ambivalence: hazy synths shimmer at the edges, drums swing between live‑sounding grooves and woozy loops, and her voice slips from smoky jazz phrasing to conversational raps. Juniper doesn’t chase anthems; instead, it presents a series of snapshots from a young woman wrestling with depression, identity, and the pressures of fame, finding solace in humour and melody even when the subject matter is heavy. — Tai Lawson

Reggie Becton, The Last Great American Summer

Reggie Becton steps into sunlit territory here, long known for moonlit confessionals, heartbreak laments, and the “sad-boy” R&B undercurrents. This album marks a coming into oneself as much as coming out of sorrow, and you can feel both past and present in every note. The Last Great American Summer frames identity, age, growth, mortality, Freedom over Fear, and Passion (“fire”) as necessary fuel. His struggle is with what it means to reach 30, what it entails to live by one’s own terms, and what it means to be authentic rather than cutting corners. “Die Young” isn’t about early death, but about choosing urgency over complacency. “Purple Rain OG” invokes legacy, homage, and nostalgia even as it pushes forward. The album refashions his sound, and there are duets (Tiara Thomas on “Simple”) that add tenderness, as well as features (D Smoke on “Fake”) that bring a bruising edge. Despite the cinematic texture, the music avoids overcoating. It keeps rough edges, so the presence remains natural. A more rooted sense of purpose can be detected in this collection than in Becton’s earlier works. As R&B evolves, nuance can sometimes be lost, but The Last Great American Summer retains nuance while expanding. Despite its comfort and warmth, this album also feels like stepping out into daylight you weren’t expecting. — Jamila W.

Parcels, LOVED

More than a return, this feels like a reconnection. After more than a decade together, Parcels took a six-month break in 2023, with each member pausing to explore and breathe. When they regrouped, LOVED originated—not just as another electropop record, but a deeply personal journey collated across continents. It’s about the strain and sweetness of love lost, love gained, love you thought you didn’t deserve. They hang somewhere between tenderness and longing, often knowingly aware of their contradictions. There are warm disco-funk grooves, multi-part harmonies that feel communal (you hear the band quite literally leaning in toward each other), and a rawness in the instrumentation (more live gear, more space, less polish in places) which only amplifies the emotional stakes. LOVED is a project that honors Parcels’ early glitter and dancefloor energy, while allowing weight, reflection, and a clearer sense of self to seep in. It crafts a space where joy isn’t cheap and nostalgia doesn’t mean stagnation. — Charlotte Rochel

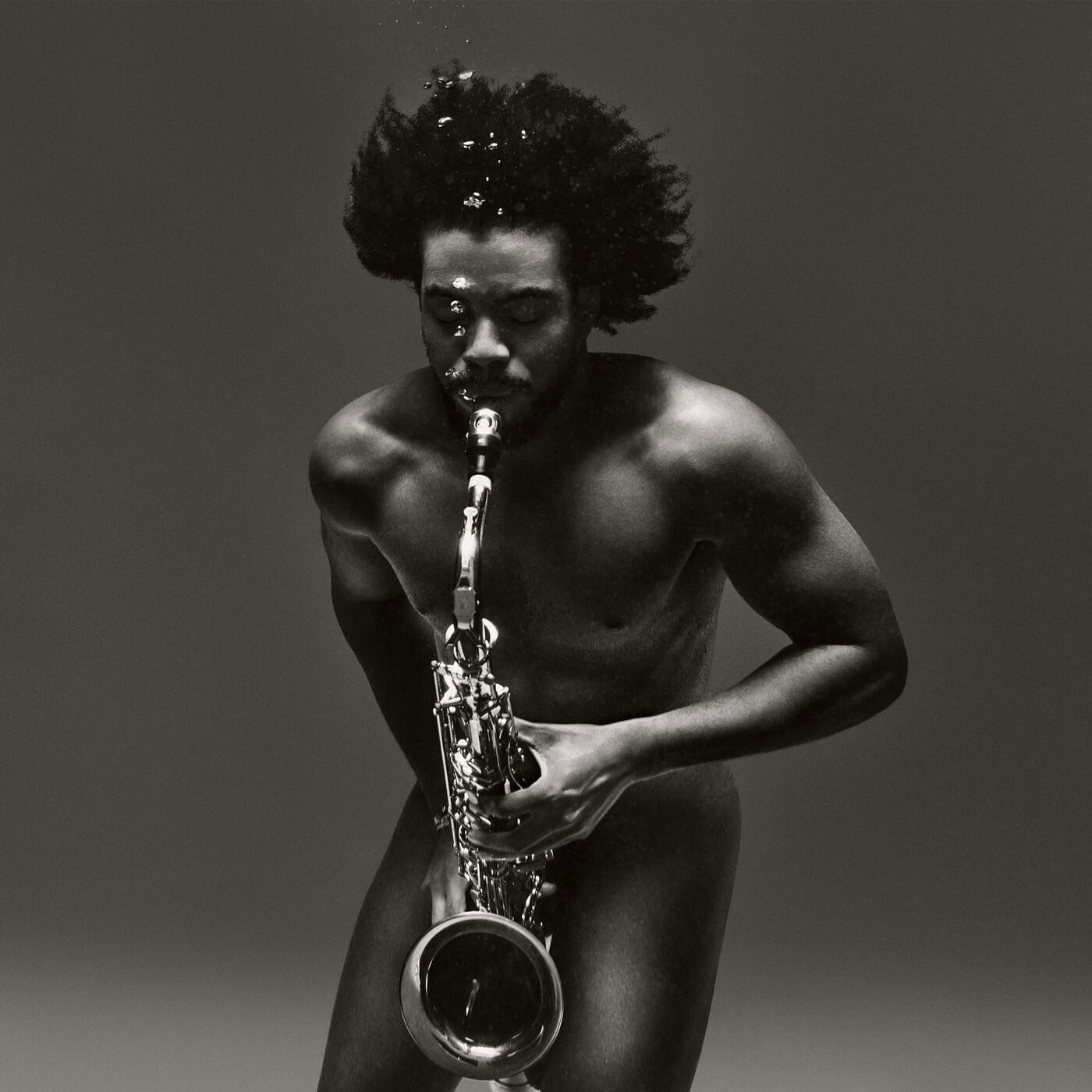

Venna, MALIK

Growing out of two EPs, Venna made his name as a saxophonist and producer moving between jazz and UK rap. MALIK feels like the moment when all the fragments of his sound—his saxophone roots, his love of soul, rap, bossa nova—finally align into something expansive and resonant. Born Malik Venner, he took his middle name from his mother’s wish that he grow into a leader, and now this release is a coming‑of‑age project and an invitation to “let go, be present and submit to sensory experiences.” The record opens up conversations about identity, legacy, and belonging; named by his mother long before the album existed, MALIK becomes a becoming. Jorja Smith, MIKE, Smino, and Leon Thomas help voice their surroundings, add layers of testimony, even when the instrumental moments speak most. There are warm acoustic guitars, percussive textures that appear intermittently, live horns paired with electronic elements, and moments of softness that shift into urgency without losing the thread. As a debut, it stands not just as an arrival, but also as a letting in of fragility, a witnessing of someone building, risking, holding both light and shadow. It belongs among the essential albums of this year, which are redefining what “modern jazz/fusion/cross-genre soul” can be. — LeMarcus

Zara Larsson, Midnight Sun

Swedish pop star Zara Larsson has chased pop stardom since her early teens, releasing platinum singles and the high‑concept album Venus in 2024. Midnight Sun charts a simpler course by stripping away elaborate narratives to deliver 10 tracks of lean, starry‑eyed scandipop. Coming in at just over half an hour, it finds Larsson trusting her instincts and reuniting with longtime collaborator MNEK, whose work across the album seems to have reignited her confidence. “Pretty Ugly” revolves around a gang‑vocal hook that refuses to leave your head and surges forward on bright piano chords. The title track swells with glittering hooks and club beats, creating an atmosphere of euphoria and endless daylight. “Crush” and “Eurosummer” fuse festival‑ready choruses with tight, intelligent writing, while “Saturn’s Return” bathes Larsson’s voice in waves of synthesizer until the song feels like an astral projection. The album may be short, but its focus allows each song to stand on its own as an invitation to dance or shout along; Larsson is honing in on what she does best, delivering unabashedly joyous pop built to ignite dancefloors and festival crowds. In returning to simplicity, she reminds us why she became a star in the first place. — Oliver I. Martin

Joviale, Mount Crystal

Joviale’s debut full‑length is less an album than a theatrical production. Growing up as a theatre kid in North London, she conceived Mount Crystal as a play before deciding to make it a record, and that narrative ambition gives the songs a cinematic sweep. Working with producers John Carroll Kirby and Jkarri, she spins a metaphysical climb through desire, danger, and desperation, drawing inspiration from Prince’s Under the Cherry Moon and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks. “The Mountain” warns, “careful not to slip and fall, you are not invincible,” setting an ominous tone that later erupts into the sinister funk of “HARK!” where she shouts, “Not even them mountains can stop you! Not even them angels can help you!” amid record scratches and guitar solos. Her improvisational spirit surfaces on “Moonshine,” a jam session where she riffs “I’m easy breezy/Sweeter than a kiwi,” while eating the fruit and channels Prince muses like Sheila E., Vanity, and Chaka Khan. Toward the end, “Blu!” offers a gentler duet between her cadence and Jkarri’s sweet‑toned synths, and “Wishing” concludes with the exchange “We have come a long way” and the answer “I go where I need to go,” leaving the narrative open‑ended. — Jill Wanassa

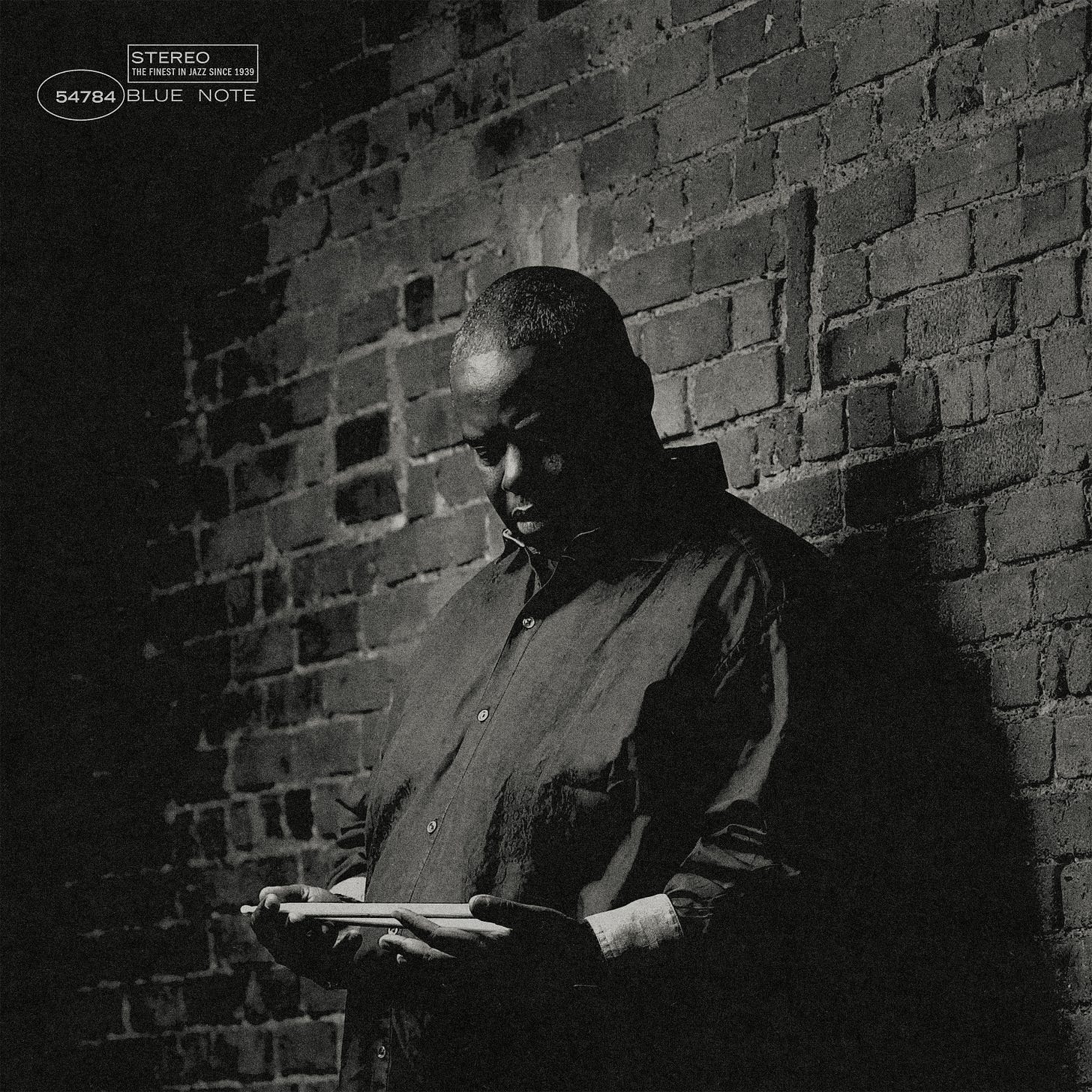

Johnathan Blake, My Life Matters

Commissioned by The Jazz Gallery Fellowship Series, Johnathan Blake returns to recording after years of building respect among jazz insiders, utilizing drumming, composition, and suite-writing to speak to heritage and urgency. His new work confronts what invisibility and injustice do to one’s sense of self by paying homage to ancestors, to familial values, to protests still unfinished. “Last Breath” channels the memory of Eric Garner, and “Can You Hear Me?” pulses with the voices of those whose voices have been stifled. Risk shows up in blending narrative interludes with intense instrumental suites; some passages might feel confrontational for listeners expecting smooth jazz, but these tensions are essential. A core group—Dayna Stephens (sax/EWI), Fabian Almazan (keys/electronics), Dezron Douglas (bass), Jalen Baker (vibes)—answers Blake’s call with both fire and space, and guests like Bilal and DJ Jahi Sundance punctuate moments with vocal humanity and sampled sound. The suite weaves between grief and hope, tragedy and resilience without settling fully into either, which makes it more alive. Among his catalog, this feels like one of the boldest statements: it doesn’t repeat but extends what he’s built, speaking not only for his life but for lives too often minimized. — Reginald Marcel

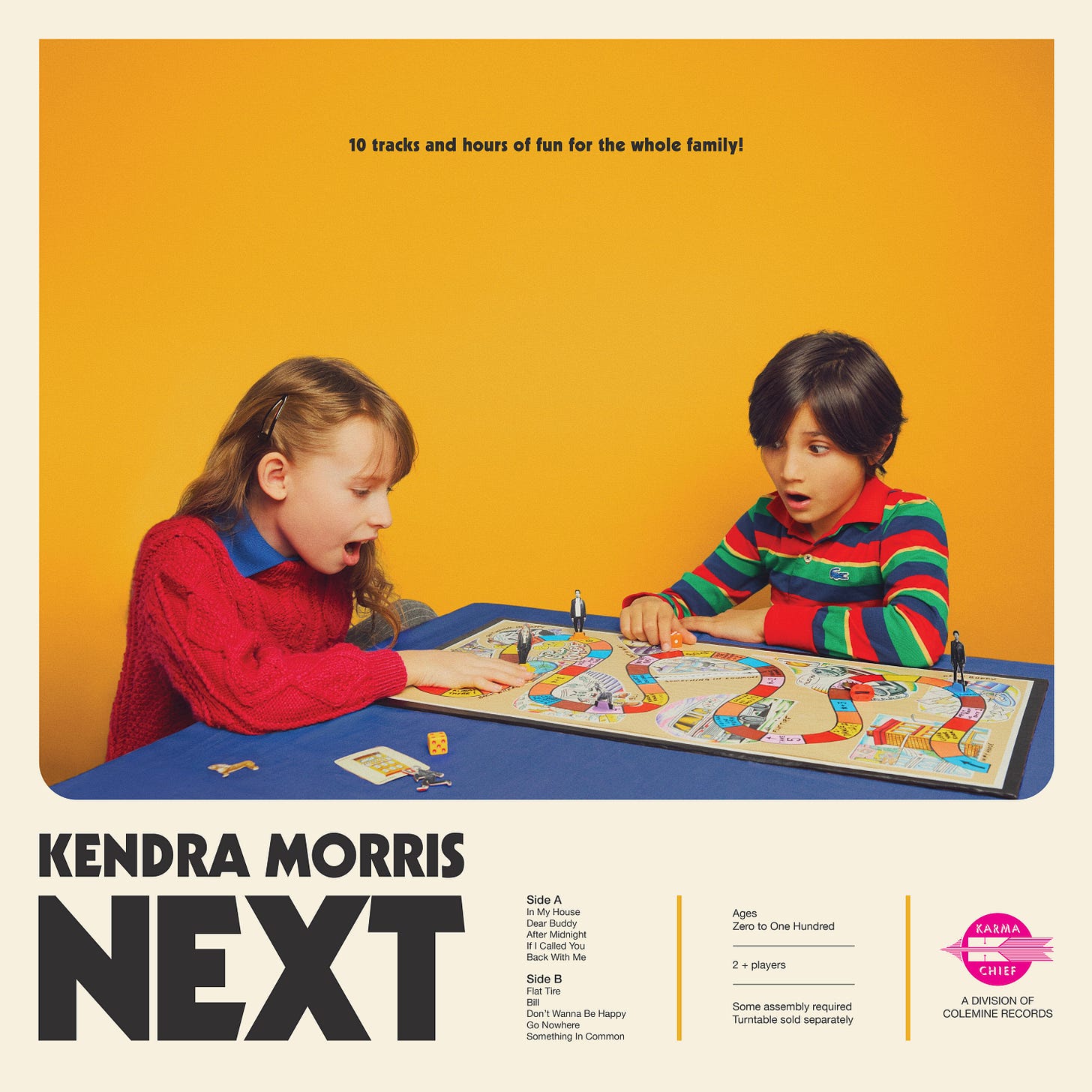

Kendra Morris, Next

After years of making cinematic soul records, singer‑songwriter Kendra Morris took a step back and built Next from the ground up, co‑producing it with Leroi Conroy and recording parts of it at Portage Studios in Colorado and in her own Brooklyn apartment. She wrote demos at her desk with a guitar, drum loops, and a Casio keyboard, and plays guitar throughout the finished album. Hence, this approach results in a more intimate, handheld feel compared to the widescreen polish of her previous work. “If I Called You” started as a slow guitar sketch before Morris and guitarist Jimmy James turned it into a breezy track reminiscent of Prince’s late‑70s work, complete with a Paisley Park‑style solo. “Flat Tire” links Kingston and Bushwick by pairing Ray Jacildo’s organ and piano with Morris’s AM‑radio‑ready voice, creating a lo‑fi reggae bounce. “Bill” is a playful ode to a recurring figure who pops up in different guises, and the delicate “Dear Buddy” functions as an open letter to her young daughter, its tender poetry and fragile strength forming the emotional core of the album. Even upbeat joints, including “In My House,” invite head‑nods while revealing shades of self‑reflection, and “After Midnight” and “Something In Common” explore raw convictions and compromise. — Imani Raven

Cécile McLorin Salvant, Oh Snap

Years of rigorous training, deep inquiry into jazz traditions, and a restless curiosity set Salvant up for this newest project, one that widens her instrumentation, her references, and her confidence. Over four years, she shaped these songs, starting solo sketches before bringing in her band and collaborators, so the album moves between intimacy and expansiveness. There’s marveling in language, in form, in what a voice can do when bent, stretched, when connected with unexpected textures. “I Am a Volcano” blends otherworldly vocals with electronics, while “Take This Stone” (with guest voices) leans toward folk harmony, and the cover verse of “Brick House” is deployed less as nostalgia. Arrangement choices surprise: synthetic elements, vocoder or house pulses, a cappella moments, swinging jazz runs, stark folk sounds. The voice is always centered but transformed, and the record never lets the formal experiment overshadow the emotional core. In comparison with her previous work, which already pushed boundaries, Oh Snap feels more expansive in its risk, yet grounded in craft, so the oddness feels generative. For those who follow jazz not only as a tradition but also as a renewal, this is Salvant in full motion—remaking what is possible, inviting admiration and challenge. — Harry Brown

Maruja, Pain to Power

Manchester four‑piece Maruja built their reputation on live shows that feel like rituals—saxophonist Joe Carroll parting the crowd like Moses and singer‑guitarist Harry Wilkinson doing push‑ups before launching into a song. The loose, jam‑like structures sometimes leave songs feeling more like fragments than statements, but when the band’s instincts click, Pain to Power conveys a visceral urgency that few debut records manage. Their style fuses post‑punk, free jazz and hip‑hop, drawing on UK scenes from Squid to the London jazz vanguard and MCs like Lee Scott and Little Simz. At its best the record catches lightning in a bottle. “Break the Tension” starts as a grinding industrial stomp before Carroll’s saxophone erupts into belching and fluttering runs, the band piling spectral backing vocals and racing percussion until the music feels like a single organism in full revolt. Opener “Bloodsport” is even more intense: Wilkinson raps over rim‑shot drums and thick bass strings, barking, “Shame so strong wanna wash away with blood… Blood calls blood, will we ever bleed enough?” as his voice shifts from spoken word to raw‑throated screams. Political anger courses through the record; the ten‑minute “Look Down on Us” targets late‑stage capitalism with grotesque images of CEOs “picking bones through their teeth” and “blood dripping down to the claws on their feet,” and Wilkinson rolls his Rs like Zack de la Rocha. Even the quieter moments namely “Trenches,” he sings about “leather lungs blackened,” turning weariness into poetry. — Phil

Saigon & Buckwild, Paint the World Black

After decades in the game, Saigon returns with Buckwild to carve out space for reflection, rage, and endurance. The collaboration feels preordained. Saigon’s lyricism is steeped in struggle, history, and aspiration, matched with Buckwild’s rugged, sample-rich palettes. There are sermons and street reports, tales of the personal and political intertwined; songs about legacy, about what’s owed, what survives. He alternates between social commentary and personal letters. “Write Back (Hear Me Now)” samples a familiar tune as he pleads for understanding, while “Well Wishes” fuses gospel and boom‑bap to express his hope that those who turned on him find peace It’s not minimalist in the sound, but it holds space where the energy comes through the shadows as much as through the light. He speaks to youth on “Whose 4 da Young?” offering words of wisdom, then pleads with God on “My Child” not to let his son grow up in a broken world. In his discography, this album togs Saigon’s earlier era—his battle-rap roots, his underground respect—with maturity: a man older, weathered, still urgent. For those who want hip-hop that doesn’t run from the weight of the world, Paint the World Black seems to answer and challenge. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Sol.ChYld, ReBirth.Theory

Sol.ChYld has always treated hip‑hop as a diary and megaphone. Hailing from Camden, New Jersey, she built her reputation on songs that pair jazz‑inflected beats with frank reflections on identity, love and the weight of living in modern America. Her 2022 record, Eyes Toward the Sun, and singles like “NBC,” which took aim at racial and economic inequality, showcased her gift for blending social commentary into her catchy sing-songy style. With ReBirth.Theory, she steps deeper into her own story. She acknowledges the pressure to “fake the funk” and promises she won’t water down her message even when that honesty costs her opportunities. She returns to family history, speaking over a mournful piano about elders who paved the way and the responsibility she feels to honor them; the hook reassures younger listeners that learning from pain is part of the journey. At some point, Sol finds her trading verses with Wiseboy Jeremy, each verse wrestling with doubt and faith; a gospel‑tinged chorus turns the song into a mantra. Moments of levity appear too, where she remembers childhood summers and neighborhood block parties, letting nostalgia breathe between bars. Without sacrificing the political edge that drew fans in the first place, ReBirth.Theory feels like a letter to her younger self and a call to everyone grappling with growth, aka the only way forward is through self‑knowledge and community. — Harry Brown

CARRTOONS, Space Cadet

Ben Carr’s music career from posting bite‑sized beat videos to leading a full band has culminated in an album that feels like a personal manifesto. As CARRTOONS, he once played every instrument himself but, for Space Cadet, he sought out dream collaborators and let each song guide the personnel. The record’s theme stems from his habit of “drifting off” and the paranoia and envy that can surface when you live online, so he locked himself away, slowed down his process and focused on things that matter rather than the instant feedback loop. Songs flit between slippery funk and slow‑motion soul, with Carr musing about jealousy in a relationship but ultimately promising to let go. On “Thursday Disco,” guest singer Haile Supreme coos over liquid bass and swirling Rhodes while Carr’s groove evokes old‑school dance floors. “Green Eyed” addresses the sting of watching a partner’s social media feed; a buttery guitar lick and stacked harmonies turn it into a confession disguised as a jam. By inviting a cadre of friends and heroes (including Phonte, Wiki, Topaz Jones, etc.) and allowing each song to speak, Space Cadet reads less like a beat tape and more like a shared diary, where funk grooves and candid lyrics coexist and jealousy gives way to joy. — Imani Raven

cktrl, Spirit

From Lewisham rehearsals on sax and clarinet to fashion-house commissions and a string of acclaimed EPs, Bradley Miller’s path to cktrl has treated melody as ritual and community practice. Spirit takes shape as a full-length that treats communion literally: breath, bow, and pulse moving as one, with prelude singles “Balance” and “Rush” sketching a throughline of tenderness and lift. Across the record, he folds clarinet and reeds into chamber-like strings, lets hand percussion and soft electronics carry the air between phrases, and privileges space so notes feel spoken rather than stacked. The guiding idea lands in a line he’s shared—“Our spirit is our light”—and the writing honors that credo by favoring clarity over spectacle, intimacy over display. Years of scene-building in South London, the poise of yield, and a widening circle of collaborators who understand that jazz, neo-classical language, and ambient drift can coexist without canceling each other out. As a debut album statement, Spirit reads like an artist stepping forward without noise, inviting us to breathe with him and leave a little lighter than we arrived. — Imani Raven

Halima, Sweet Tooth

Halima steps into her full debut here after the promise of her EPs, pulling together years of hidden sketches into something that pulses precisely. It’s an odyssey through desire, regret, long nights, and stolen moments—what started in fragments becomes a coherent map of self-reckoning. The record shifts between shimmering R&B and club-ready Afro-pop, with spectral ballads (“Laundromat”, “November Like u”) giving way to polished, urgent tracks such as “Cocoa Body” and “Sweet Tooth.” Production by Mikey Freedom Hart, among others, gives lush textures, bittersweet harmonies, and a dynamic undercurrent of sensuality. Sweet Tooth feels like a full-throated emergence that she’s arrived, but that she’s also understood what she wants to say and how she wants it to sound. She threads these vignettes together with a mantra—“sweetness on my terms”—that runs through her writing, using sweetness not as naïveté but as a choice, insisting that vulnerability and strength can coexist. It’s for anyone who loves albums with pulse and vulnerability, feeling like flipping through a photo album of nights out and mornings after, each song offering a different angle on the pleasure and pain that come with learning to set your own boundaries. — Ameenah Laquita

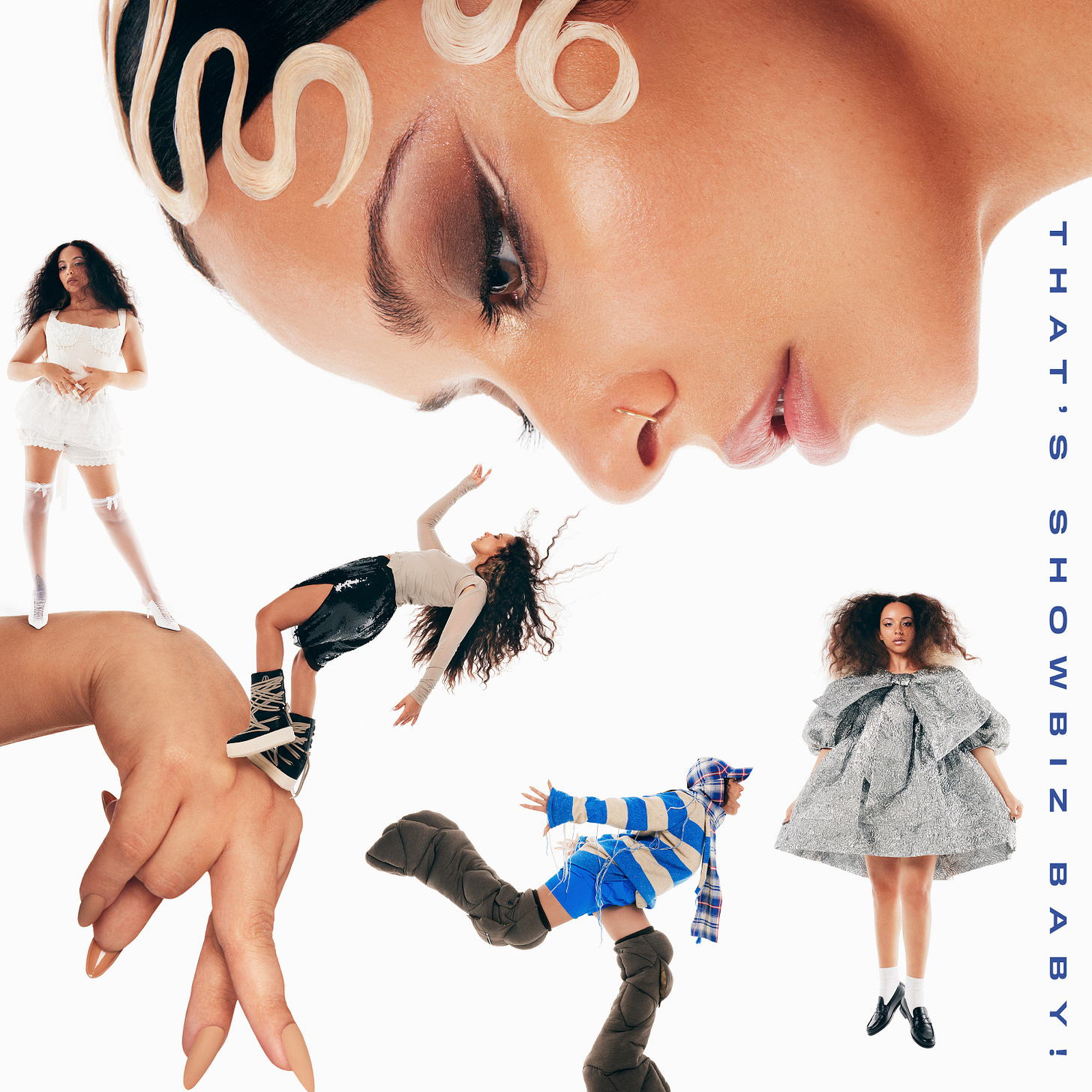

JADE, That’s Showbiz Baby!

Having spent a decade topping charts with the pop group Little Mix, Jade Thirlwall—now performing simply as JADE—steps into the solo spotlight with an album that gleefully dismantles the machinery that once propelled her. She has spoken about the speed‑dating approach she took in early sessions, rushing to find collaborators because she feared people would forget her after Little Mix, and that anxiety becomes part of the record’s narrative as she rewrites her relationship with fame. That’s Showbiz Baby! is a pop album steeped in the sounds of her youth—Euro‑dance, disco, synth‑pop—but its real strength lies in its songwriting. “Angel of My Dreams” handles fame as a double‑edged sword, interpolating Sandie Shaw’s “Puppet on a String” and turning the puppet motif back on industry figures (“selling my soul to a psycho”). Her humor is front and center on “FUFN (Fuck You for Now),” which chronicles a drunken fight and the burnout of a grind‑heavy pop career, and “Plastic Box,” a synth‑pop confession about projecting toxicity onto a partner. What ties the album together is JADE’s refusal to shy away from messy emotions—she plays with campy humour and dance‑floor exuberance, yet repeatedly returns to questions of autonomy, fame’s cost and bodily honesty. — Charlotte Rochel

Rochelle Jordan, Through the Wall

Rochelle Jordan has been quietly redefining club‑ready R&B for more than a decade. After her 2014 album 1021 and the adventurous Play With the Changes, she returns with a project that treats the dance floor as a sanctuary rather than a trend. Jordan describes Through the Wall as a dedication to God and to herself – an album born of breaking through psychological and professional barriers and celebrating the artist she has become. The songs are steeped in the deep grooves of Chicago house and New York ballroom and coloured by her Canadian and UK roots. “Crave” rides a rich, pulsing bass line and invites listeners to get lost in its hypnotic swing, while mid‑tempo numbers include “Never Enough,” “Get It Off,” and “Bite the Bait” recall the seductive pull of ‘90s R&B. She pays homage to UK garage on Close 2 Me, whose bassline demands a loud soundsystem and thick smoke. On “Ladida,” Jordan flips from airy singing to a swaggering rap over a shuffle beat, accompanied by a playful vocal tic that conjures memories of Crystal Waters and basement raves. She sounds empowered, writing a love letter to freedom and asserting her individuality over industry fads by crafting a dance record that moves both body and spirit. — Tabia N. Mullings

Ho99o9, Tomorrow We Escape

On Tomorrow We Escape, Ho99o9 their most personal statement yet. Over the past decade, theOGM and Yeti Bones have mutated hip‑hop, punk and industrial noise into a form of engineered chaos. The opener “I Miss Home” featuring MoRuf sets the tone with a dense, industrial backdrop and vulnerable lyricism, while “Upside Down” uses frenetic keys, warped guitars and danceable basslines to balance assault and introspection. “Incline,” produced by Sitek and featuring Nova Twins, Pink Siifu and Yung Skrrt, bursts with chaotic energy, and “Target Practice” snarls at critics with “Give a fuck where you at/Give a fuck where you from.” “Tapeworm” pairs Greg Puciato’s vocals with searing riffs, “Immortal” floats Chelsea Wolfe’s voice over creaky guitars in what might be the duo’s most emotional track, and the finale “Godflesh” explodes with double‑bass drumming and punk‑speed riffing before glitching into the chant “Born dead. God’s flesh.” Long‑time fans get the adrenaline rush they expect, but there are moments of vulnerability and personality. By uniting cathartic screams with quiet admissions, Tomorrow We Escape illustrates that even the most confrontational music can house introspection. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Amie Blu, When All Is Said and Done

Amie Blu came up in London’s DIY scene with a voice that could sound both world‑weary and playful. Since the last year’s EP under the 0207 Def Jam banner, she’s ready to spread those wings. Her debut album channels those qualities into a candid portrait of depression and healing. The song titles alone hint at the heavy mood and Blu treats the record like a confessional letter. Early on, she sings about feeling stuck, using bright guitar chords and gospel‑tinted vocals to mask lyrics about drowning in self‑pity; the contrast is deliberate, as she enjoys placing upbeat surfaces over darker sentiments. Riding on a country‑soul shuffle she addresses a lover directly, insisting that she won’t let their affection go to waste and admitting she’s been afraid to speak her mind. The plea “take me as I am,” tucked into a sparse piano ballad, finds her acknowledging her flaws and asking for unconditional acceptance. On “Shadow,” she layers bubbly synths over a melody about feeling invisible; the song was powerful enough to earn a co‑sign from SZA. Another highlight comes when she writes from her cat’s perspective, turning a simple acoustic arrangement into a metaphor for fragility and prompting fans to show photos of their own pets during shows. Blu says she wrote the album with friends to make honesty easier, and that process shows, beginning with self‑loathing and ending with an anthem about finding a way forward. — Charlotte Rochel

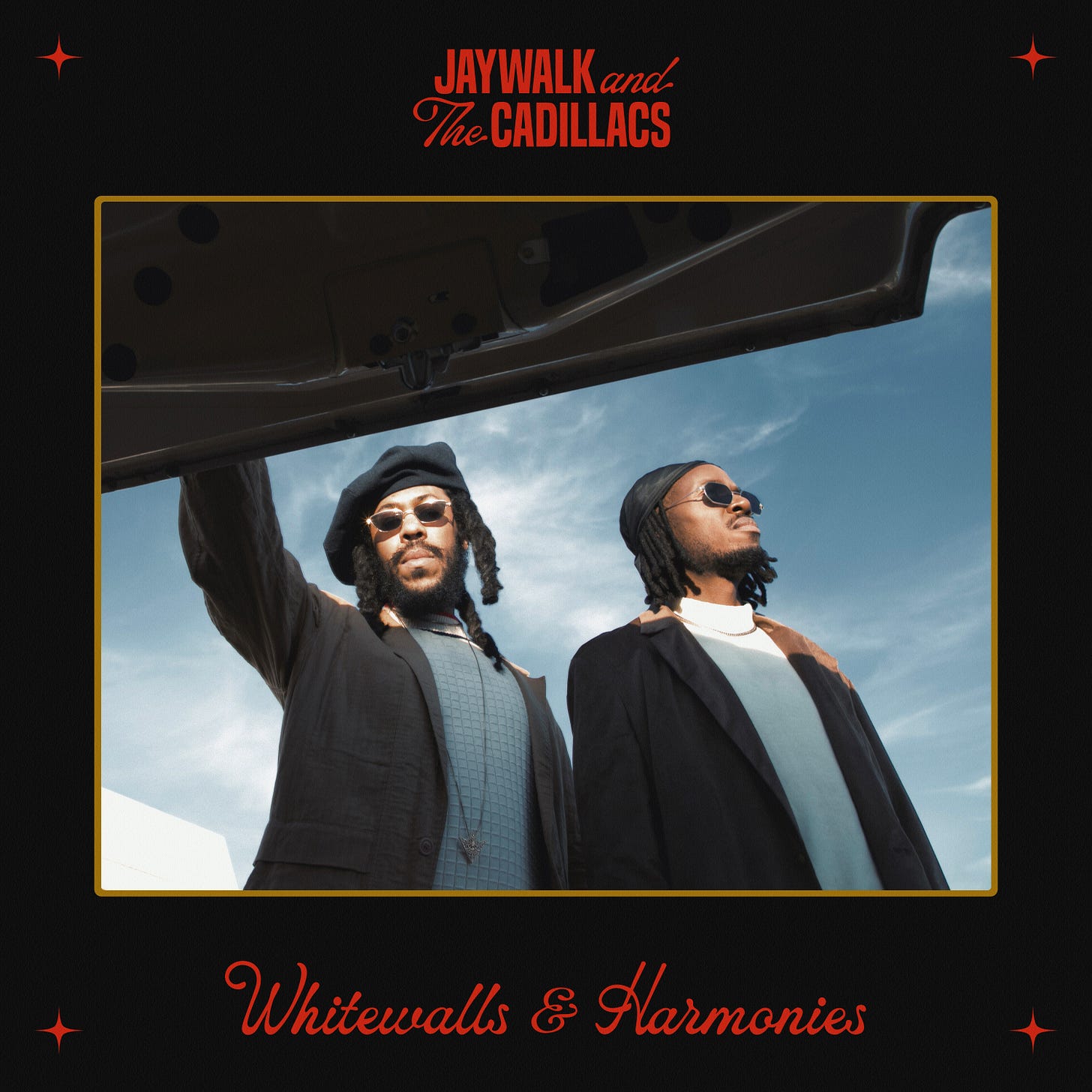

Jaywalk and the Cadillacs, Whitewalls & Harmonies

Ash Walker has spent years blending dub, jazz and hip‑hop in his solo work, while Illa J carries the legacy of his brother J Dilla as both rapper and producer. Together as Jaywalk and the Cadillacs, they’ve crafted a debut album that reflects jam sessions in London, Iceland and on the road. The record opens with a slow‑burning love song where Illa J croons over Walker’s electric piano, asking if his devotion will be returned; the groove is thick with analog warmth. From there, he duo shifts into head‑nodding neo‑soul and downtempo jazz, inviting artists such as Harleighblu and Ke Turner to trade verses about hangovers, temptation and inner conflict. Turner’s nimble bars on “Danger” with shimmering Rhodes and a hook about feeling priceless even when circumstances threaten to dull one’s shine; the track hints at the album’s title with a metaphor about whitewall tires rolling through troubled streets. The record peaks again when Frank Nitt appears to recount a dream sequence that flips from anxiety to hope and back, only to reprise as a meditative piano piece featuring classical pianist Belle Chen. The musicianship throughout the album feels loose but never sloppy. Whitewalls & Harmonies celebrates the idea that hip‑hop and Neo-soul can be expansive without abandoning its roots, fusing live instrumentation and lyricism into a vivid soundscape. — Harry Brown

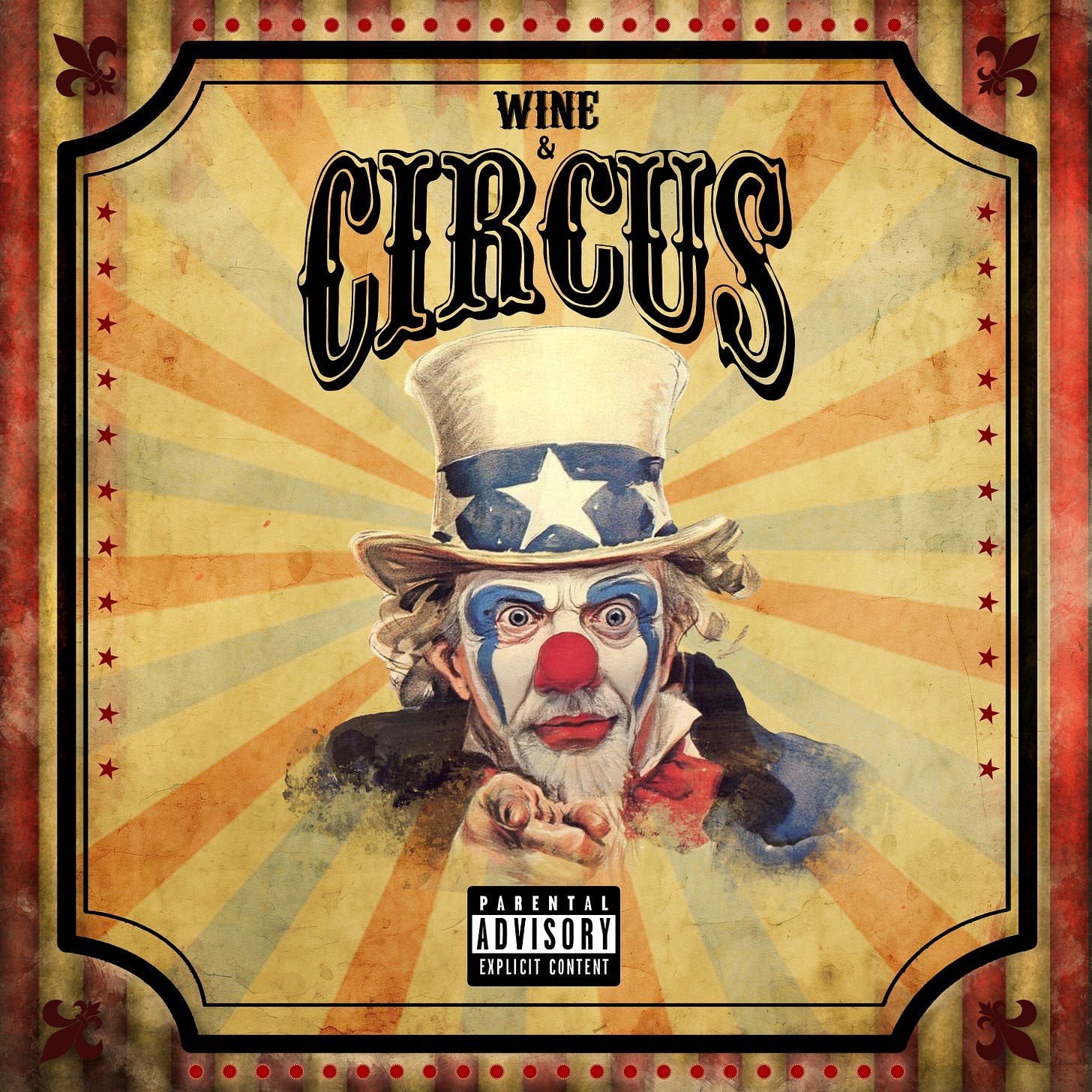

Locksmith & The Heatmakerz, Wine & Circus

With years of craftsmanly lyricism and viral freestyles under his belt, Locksmith partners with The Heatmakerz to build Wine & Circus around urgency: the extravaganza of modern life, the noise of politics, and the duel between public performance and private conviction. The album holds tension between spectacle (“circus”) and indulgence (“wine”), asking what happens when activism becomes entertainment, when truth is filtered through expectation. “Culture” (featuring Styles P) pulls no punches about power structures, “Under Pressure” questions complicity, and “Closed Caption” exposes what’s said and unsaid in media and life. Emotional stakes are high when honesty overrules comfort, calling out hypocrisy over silence, and the weariness under resistance. There is a vibrant pulsation in the Heatmakerz’ samples, ranging from soul to vintage cuts, piano, and boom-bap drums, so Locksmith’s cadence carries the whole track—his flow shifts from quiet anger to razor-sharp delivery, spitting bars that weigh both assertion and doubt. Angel Hill adds a softer counter-voice, Joell Ortiz lends weight on “Closed Caption,” and Mysonne adds reflective counterpoints. It’s lean, but rich in variation, featuring political critique, personal reflection, poetic lines, and no filler. Wine & Circus is a reminder that lyricism still matters, that rap can bite and heal, that collaboration between a strong MC and a storied production duo can still produce anger, beauty, and clarity together. “You hit the nail’s head: What if, instead of Sexyy Red, it was sexy to be well‑read?” asks Bay Area wordsmith. — Phil