Shenae “Curry” Craig Built Rooms Where Black Women Could Speak Freely

Her organizing was intimate and disciplined. She made space for truth without asking anyone to shrink.

A wicker basket sat at the entrance. Phones went in before bodies passed through. Shenae “Curry” Craig enforced that rule at S.A.F.E., the gathering she designed for Black women and professionals of color who needed a gathering stripped of surveillance. No recording, screenshots, or content captured for someone else’s timeline. Craig collected the devices herself, stacking them in that basket the way a hostess collects coats, and the gesture carried weight precisely because she did not soften it with apology. The boundary preceded the conversation. If you wanted to enter, you surrendered the instrument most likely to betray you.

Inside, women talked about salary negotiations that had gone sideways. They named supervisors who took credit. They described exhaustion without performing resilience. The privacy policy functioned on the strength of consequence removal. A corporate diversity panel invites you to speak and then circulates the footage. Craig’s model reversed that architecture. She built a container where admission required a small act of trust, and the trust paid dividends in candor. Women disclosed things they would not repeat at brunch, let alone on a podcast. The room held on the strength of someone who had decided in advance what it could not become.

Specificity defined Craig’s method across every project she assembled. A sign-in sheet at the door. A group text going out early in the morning to confirm who was bringing what. A DJ controller plugged in and levels already set because she had tested the sound an hour before anyone arrived. Craig, a Brooklyn-born event curator, journalist, and community organizer, approached gathering the way a contractor approaches framing. She measured first. She secured permits. She did not invite people into a structure she had not load-tested.

Craig’s journalism carried the same discipline. As an editor at Secret NYC, she covered restaurants, culture, and neighborhood happenings across the five boroughs with a particular gravity toward Black-owned businesses and the Caribbean diaspora she belonged to. Her bylines for Blavity, Travel Noire, and Yahoo News stitched together food criticism, lifestyle coverage, and cultural reporting with a Brooklyn-specific knowledge that could not be faked. She knew which West Indian bakeries closed on which days. She knew the subway transfers that tourists botched. Granular familiarity powered the writing; she did not parachute into neighborhoods. She walked through them carrying grocery bags.

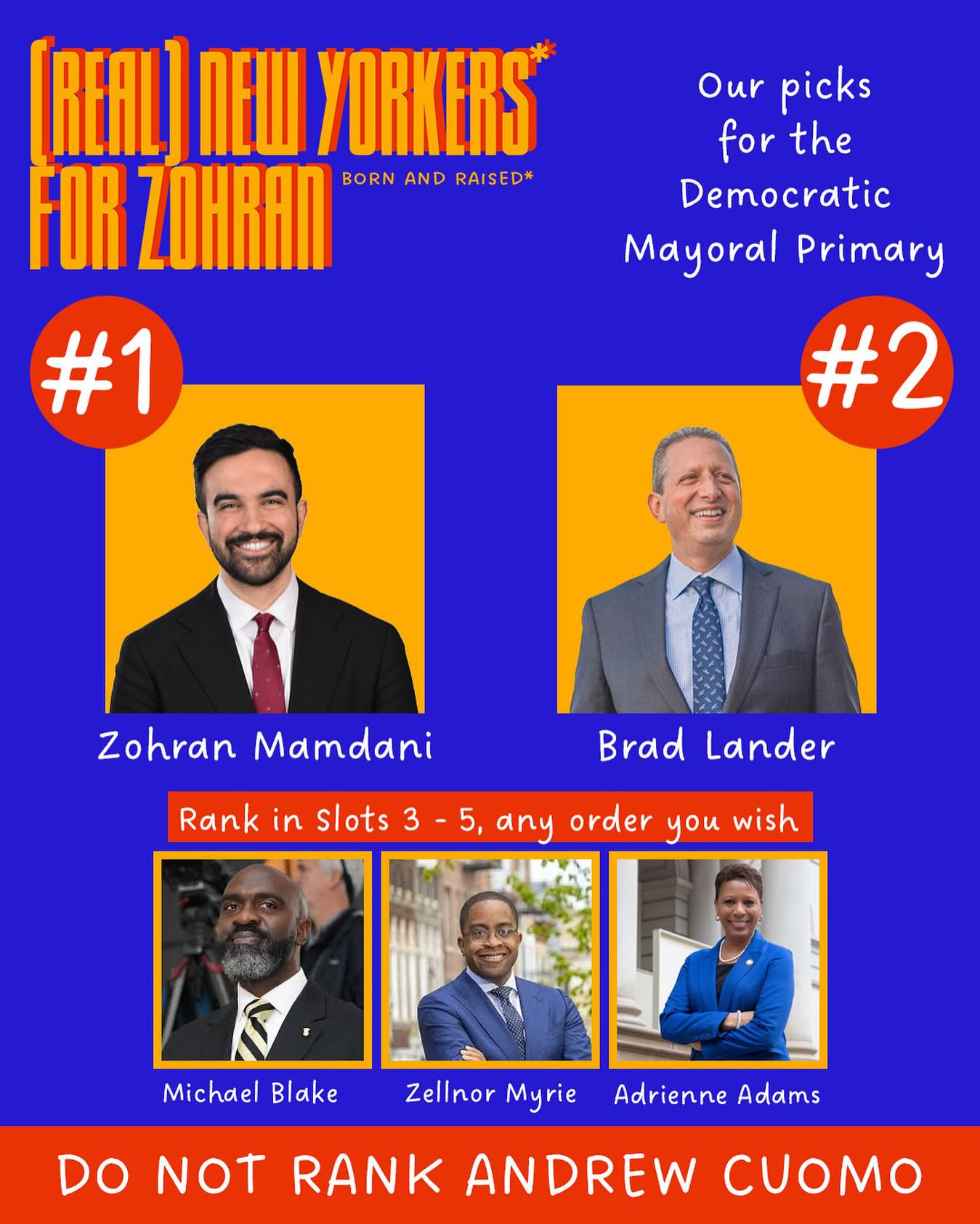

Political organizing through We Grew Here (which helped Zohran Kwame Mandani secure the mayoral win) extended that local intelligence to door-knocking, canvassing for candidates with roots planted deep enough to recognize which intersections people called by unofficial names. She spoke to voters the way you speak to someone you might see at the laundromat later. Clipboard tucked under her arm. Lanyard swinging from her neck. She trained volunteers not on messaging but on listening. Her requirement was direct. If you canvassed with her, you knocked and then you shut your mouth until the person on the other side of the door finished talking. The method was slow and it was effective, grounded in the assumption that the voter already knew what they needed. Craig’s contribution was showing up at their stoop and asking.

The same instinct powered Don’t Call Me Baby, the women’s sports and culture platform she founded alongside Sharine Taylor, a Toronto-based editorial strategist. The project was built on a stubborn premise. Women athletes deserved coverage that did not shrink their lives to box scores and postgame interviews. Craig attended New York Liberty games at Barclays Center with a credential around her neck and a phone aimed at the crowd as often as the court, capturing the community that orbited the franchise. She covered WNBA culture as civic infrastructure, treating ticket holders and tailgaters with the same attention other outlets reserved for star players. The platform’s mission committed to chronicling women athletes beyond the game, advocating for women and girls in sports via storytelling that respected their full lives.

Don’t Call Me Baby functioned on the same asperity Craig brought to every room she assembled. She curated contributors. She set content standards. She decided what the platform would not publish as firmly as she decided what it would. Taylor handled operations and editorial strategy from Toronto. Craig handled community from Brooklyn, pressing her network of writers, DJs, and cultural workers into service around a shared conviction that women’s athletics warranted sustained, serious attention rather than seasonal curiosity.

In November 2022, her body interrupted that momentum. Days before her thirty-first birthday, Craig discovered a lump in her left breast during a shower. Her family history sharpened the terror. Two of her mother’s sisters had battled breast cancer. One of them died in Jamaica. Craig scheduled a biopsy for November 9, the day after her birthday. The results confirmed stage 2 breast cancer.

Treatment stacked on top of her existing life like paperwork on a desk that was already full. Chemotherapy sessions at Memorial Sloan Kettering. Radiation. A double mastectomy followed by reconstructive surgery with tissue expanders that required weekly saline fills. Fertility preservation through egg retrieval and freezing, a procedure necessitated by her age and the chemotherapy’s threat to her reproductive capacity. Craig endured months of aggressive treatment while calculating which assignments she could still file and which events she could still attend between infusion days. The fatigue was physical and total. She described the post-surgical period as a dark passage where her body no longer felt like her own, a disorientation compounded by hair loss and the altered silhouette she confronted each morning.

She beat the initial diagnosis. She rang the bell at Sloan Kettering. She resumed writing. She picked up DJ gigs. She went back to covering Liberty games. Katherine Polanco, her best friend of twelve years, had organized the first GoFundMe to offset medical bills that insurance declined to cover. Craig returned to the structures she had raised, thinner and slower but present.

March 2025 brought the cancer back. Metastatic breast cancer. The disease had migrated to her bones. At thirty-four, Craig confronted a diagnosis that oncologists classify as lifelong, managed rather than defeated. The pain became daily and severe. The fatigue compressed her schedule into shrinking windows of capacity. Many days confined her to her bedroom. She could not work. Her cousin Samantha Riddell organized a second fundraiser to cover groceries, bills, and a trip to Jamaica that Craig had been planning for years, a visit to ailing family that the first diagnosis had postponed and the second threatened to cancel entirely.

Even through that contraction, Craig’s infrastructure held. Don’t Call Me Baby continued publishing. The standards she had codified for the platform did not depend on her physical presence at every event. She had trained collaborators and established guardrails before her health forced delegation. Taylor kept the Toronto side running. Contributors filed stories shaped by the parameters Craig had hammered into place during healthier years. The rooms she constructed did not require her body in the doorway to remain functional. They required her rules, and those rules survived her absence; she had written them down and enforced them long enough for other people to internalize them.

Persistence is what distinguishes Craig’s legacy from the softer tribute language that so often follows Black women who organize. She did not offer comfort without structure. She erected walls and enforced what passed through the door. She did not amplify voices. She collected phones so that a whisper could carry its full weight. The distinction matters. Craig understood that safety is architectural. You cannot wish it into existence. You install it through policy, repetition, and the willingness to tell someone at the door that their device stays in the basket or they stay in the hallway.

Those rules outlast her. The S.A.F.E. model circulates among Black women professionals who attended her gatherings and replicated the phone policy in their own organizations. Don’t Call Me Baby publishes at dontcallmebaby.club, its voice carrying the standards Craig established with Taylor before the first diagnosis altered her calendar. The credential lanyard, the group text, the sign-in sheet, the tested sound levels. These are not memories. They are protocols, maintained by people who absorbed them from a woman who understood that a room without rules is a room where someone eventually gets harmed.

Shenae “Curry” Craig died on Thursday, February 12, 2026. Thank you for what you have contributed. She will forever be missed.