Singers Painting R&B in the Colors of Heart-Flutters

After “So Sick” conquered the charts, a wave of melodic R&B singers found their audience in Tokyo. These Ne-Yo disciples built careers on falsetto and heartbreak.

He may be insufferable now, but since In My Own Words, Ne-Yo rescued the melodic warmth that mainstream R&B had traded away for edge during the late ‘90s and early 2000s. After “So Sick” climbed the charts, Ne-Yo and his production partners Stargate found themselves flooded with clients chasing that same tearjerker blueprint. A few years behind them came the Ne-Yo followers. In Japan, where melodic R&B commanded devoted audiences, these imitators drew serious attention, and the music often sparked bigger excitement there than in the States. Marketed as “heartstring R&B” or “tokimeki R&B,” these artists built careers on vulnerability and pristine falsetto. Among the most prominent was Stevie Hoang, a UK-born singer with Chinese-Vietnamese heritage whose “One Last Try”—draped in fantasy-world harp arpeggios straight from the “So Sick” playbook—ignited his following. Beyond singing, Hoang also produced for UK male vocalists like Kay B, Shay, and Melico X.

Stateside, Tim Benson’s Insomniax-helmed Formula stood out, complete with a cover of Ralph Tresvant’s Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis-penned “Sensitivity.” Songwriter Lil’ Eddie, who’d placed songs with El DeBarge, traced the “So Sick” template on his debut. Razah, who inked a deal with Def Jam under Jay-Z’s watch but never landed his album domestically, instead bowed in Japan with a vocal style closer to Steve Russell’s Michael Jackson imitation (Razah doubled as a reggae singer). Atozzio’s The Imprint dropped listeners straight into heartstring territory with a harp-sweetened duet alongside Tynisha Keli. The Jackie Boyz, contributors to that same record, had written splashy hits for Flo Rida and Madonna, yet their Japan releases softened into this tokimeki mold. Their best-of compilation includes a cover of MJ’s “Human Nature.”

Stevie Hoang, This Is Me (2007)

Recorded in a London bedroom with no label support and no studio budget, This Is Me became a Japanese import phenomenon before most Americans ever heard the name. Hoang self-produced every track, sang every harmony, and uploaded the results to YouTube, where audiences in Tokyo discovered him faster than any A&R scout. The album hinges on “One Last Try,” whose harp runs and pleading falsetto positioned Hoang as the UK answer to Ne-Yo’s ballad dominance. He begs for reconciliation across three minutes of crystalline synths, his voice thin but controlled, the desperation convincing enough to forgive the occasional pitchy run. “Addicted” slows the tempo further, Hoang murmuring about obsession while a muted kick drum taps beneath him like a heartbeat. “No Games” offers the closest thing to uptempo energy here, though even its rhythm track pulses with melancholy.

What Hoang lacks in raw vocal power he compensates for with clarity of intent. Every lyric fixates on romantic suffering or romantic hope, and he means all of it. “Before You Go” finds him bargaining with a departing lover over a bed of piano chords and string pads, his voice cracking on the high notes in a way that reads as authentic rather than amateur. “If I Was the One” imagines himself as a better boyfriend than whoever currently holds the position, a premise he sells with conviction even when the writing tilts toward diary-entry simplicity. The production rarely surprises, but Hoang understood his audience wanted consistency more than experimentation. Japan rewarded that instinct with sales exceeding 65,000 copies, enough to earn him a record deal and a decade-long career built on this exact formula. — P

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

A bedroom-produced debut that found its audience across the Pacific, trading vocal fireworks for the kind of earnest pleading that made Ne-Yo’s ballads inescapable. Hoang’s limitations become assets when framed as intimacy.

Tim Benson, Formula (2009)

Chicago singer Tim Benson partnered with production duo the Insomniax for an album that wears its influences openly, including a cover of Ralph Tresvant’s “Sensitivity” that updates Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis’s new jack swing original with smoother drums and digital sheen. Benson’s tenor holds the same boyish fragility Tresvant brought to his solo debut, though without the Motown machinery behind him. “Again and Again” opens with a confession of repetitive heartbreak, Benson cycling through the same romantic mistakes and admitting as much over a mid-tempo groove. “Someone Else Will” threatens to walk away from a neglectful partner, the ultimatum tendered without bravado, his voice dipping into its lower register for the verses before climbing on the hook.

The production leans toward early-2000s smoothness, drum programming that avoids sharp edges, synth pads that hum rather than punch. “Reconsider” makes the case for a second chance with a melody that recalls Tresvant’s ballad phrasing, Benson’s voice light and slightly nasally as he lists reasons to stay. “Kiss From You” surrenders negotiation for pure longing, the arrangement stripped to keys and restrained percussion while he catalogs what he misses. “Meet Me Halfway” asks for compromise without demanding it, the request as tentative as the gently swinging beat beneath.

Where Formula falters is in its sameness. Benson possesses a pleasant instrument but rarely pushes into uncomfortable territory. The album presents itself as a remedy for aggressive R&B, a return to sensitivity as governing principle. That mission succeeds. Whether it lingers depends on how much you need another “Sensitivity” in your rotation. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

A devotional to Tresvant-era tenderness, produced with competence and sung with appropriate fragility. Benson believes in the love song as emotional balm, and Formula dispenses that medicine reliably if not memorably.

Lil’ Eddie, City of My Heart (2009)

Edwin Serrano bounced between labels for years before landing this debut through a Japan-first release strategy that became standard for tokimeki R&B hopefuls. His songwriting credits for El DeBarge and later Fifth Harmony suggested commercial instincts, but City of My Heart swaps hitmaking calculation for extended vulnerability. “The One That Got Away” announces his thesis across five minutes of regret, Serrano cataloging everything he should have said to a departing ex while strings swell beneath him. His voice carries a rasp that separates him from the smoother tones dominating this subgenre, a slight grit that reads as world-weariness rather than technical limitation.

“Searchin’ for Love” couples him with Mýa for a duet about parallel loneliness, both singers circling each other without quite connecting, the production warm but distant. “Statue” became the album’s cult favorite, later amplified when BTS’s RM posted about it years after release, sending streams into the millions. The song deserves the attention. Serrano sings about freezing under emotional pressure, unable to speak or move when it matters most, his falsetto controlled but clearly strained. “Grown N’ Sexy” attempts a tempo shift, aiming for club relevance with thicker drums, though Serrano sounds more comfortable in the slower material.

His Filipino-Puerto Rican heritage surfaces in the phrasing, certain syllables stretched in ways that distinguish him from the Southern-inflected vocalists dominating American R&B. “Confetti” closes the album with Che’Nelle, the two exchanging verses about post-breakup disorientation, their voices merging on a hook that imagines scattered remnants of a relationship. Serrano would eventually find bigger paydays behind the scenes, but City of My Heart captures him as a singer who meant what he sang. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

A songwriter’s album that benefits from its creator’s investment in the material, Serrano’s rasped delivery adding texture to productions that might otherwise blur together. His gift for specificity keeps the confessions from turning generic.

Razah, I Am Razah (2010)

Jamaican-born, Brooklyn-raised Martell Nelson signed to Def Jam after JAY-Z walked into a studio session unannounced and heard potential in his voice. The album that resulted never landed in America. Instead, Razah bowed in Japan with material that splits the difference between reggae smoothness and Michael Jackson phrasing, his tenor flexible enough to handle both. “Rain” pleads for emotional relief through weather metaphor, Razah begging the storm to carry him away from heartbreak, his delivery more crooned than belted. Stargate handled production on several tracks, their fingerprints visible in the polished drum programming and layered synths.

“Where Do We Go” earned attention when Rihanna, then labelmates with Razah at Def Jam, added her voice to a remix. The original version presents Razah alone, questioning a stalled relationship with genuine uncertainty, his Jamaican accent surfacing on certain vowels before retreating into American R&B convention. “Dear Dad” addresses the father he never knew, the confession direct and unguarded, Razah naming his confusion without self-pity. “Girlfriend” veers toward his reggae roots, the rhythm lighter, his phrasing more syncopated, the song about devotion rendered with Caribbean warmth.

The MJ comparisons came inevitably. Razah’s falsetto retains traces of Jackson’s breathier moments, and his mid-range recall the young Michael of Off the Wall more than the theatrical presence of Thriller. “Higher” reaches for spiritual uplift, the production swelling into gospel territory while Razah promises transcendence. He writes all his own material, a distinction he emphasized in interviews, insisting the emotions captured here belonged to him personally. The album stalled commercially in every market that released it, but Razah succeeded in capturing a specific vocal identity that blended his Jamaican heritage with American soul training. — B.O.

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

A Def Jam signing stranded by label politics, Razah filters his Caribbean roots through MJ-inflected phrasing, the combination distinctive even when the songwriting settles for convention. His voice earns the comparisons it invites.

Atozzio, The Imprint (2011)

Atozzio Towns spent years placing songs with Chris Brown, Mario, and Jay Sean before stepping to the microphone himself. His debut begins with “Reasons,” a duet alongside Tynisha Keli that drapes harp arpeggios over their tangled excuses for why a relationship keeps failing. The pairing establishes The Imprint as heartstring bait, two voices orbiting blame and attraction simultaneously, neither willing to walk away despite the evidence. “I Quit” follows with Atozzio alone, announcing surrender to romantic pursuit, his voice fuller than the brittle tenors common in this lane, a baritone warmth that grounds the vulnerability.

His songwriting background emerges in the craft of these confessions. “Without You” features the Jackie Boyz swapping verses about codependency, the three voices weaving around each other while the production stays minimal. “Where Do We Go (From Here)” pairs Atozzio with Jordyn Taylor for another relationship autopsy, both singers asking questions neither can answer. “Memory” brings Christina Milian aboard for the album’s most commercially polished moment, her recognizable tone floating over synth washes while Atozzio anchors the verses.

What distinguishes The Imprint from its genre neighbors is Atozzio’s willingness to document failure specifically. “Conceited” addresses a partner too self-absorbed to notice his devotion, the accusation voiced without cruelty. “Wrong” examines his own mistakes with equal honesty. The production, handled partly by Rodney Jerkins, stays clean and unhurried, prioritizing vocal clarity over rhythmic complexity. Towns would later attribute the album’s emotional directness to personal experience, describing each song as a chapter from his own romantic history. Whether literally true or strategically framed, the specificity registers. — P

Rating: ★★★½☆ (3.5/5)

A songwriter’s transition to performer that benefits from insider knowledge of what makes confession stick. Atozzio’s voice supplies enough weight to sell the vulnerability his pen provides.

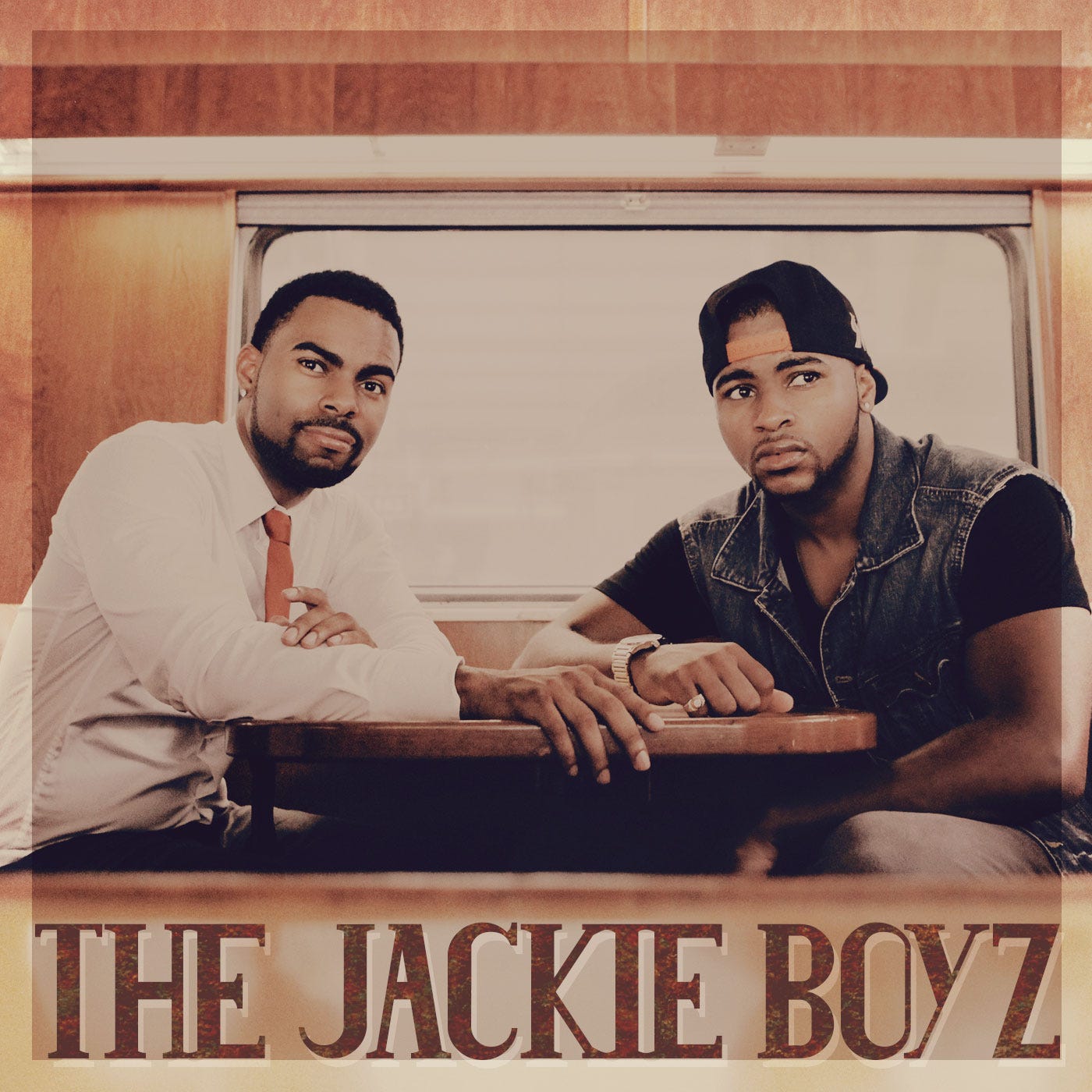

The Jackie Boyz, The Jackie Boyz (2015)

Brothers Carlos and Steven Battey started as street performers on Savannah’s River Street before becoming the songwriting team behind Madonna’s “Revolver” and Flo Rida’s “Sugar.” Their own debut album pivots away from those club-ready assignments toward the tokimeki R&B sound Japanese audiences craved. “Love and Beyond” launches the record with layered harmonies promising eternal devotion, the Batteys’ voices blending the way sibling pairs often do, blood relation audible in the matched vibrato. “Cross Country” maps a long-distance relationship through travel metaphors, the production Boyz II Men-smooth, the sentiment earnest enough to withstand the familiar imagery.

They cover Boyz II Men’s “Step On Up” as direct tribute, their voices lighter than the original quartet but harmonically tight. “Now That I’m Here” places them present for a partner who’d given up on their arrival, the lyric dwelling on the relief of finally showing up. “She’s Not Perfect” acknowledges flaws and loves anyway, the specificity of imperfection left vague but the acceptance genuine. “Paid My Dues” chronicles the hustle that preceded any success, the brothers alternating verses about struggle without self-congratulation.

Their compilation later added a cover of Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature,” the Batteys treating Toto’s melody with reverence, their harmonies tracing Steve Porcaro’s original chord voicings while their phrasing nods toward Jackson’s featherlight delivery. The original material on Love and Beyond rarely reaches that cover’s elegance, but the album demonstrates singers capable of inhabiting romantic material without irony or distance. They believed in love songs when they wrote for others. They believed in them for themselves too. — P

Rating: ★★★☆☆ (3/5)

A songwriting duo’s compilation outing as performers, the Battey brothers applying their harmony training to material softer than the hits they built for others. Their “Human Nature” cover alone justifies the detour.