Street Rap Cannot Be the Only Passport to the Mainstream

CyHi’s push for more street rap at the center of pop reignited an old argument. When one life path becomes the benchmark, everyone else is cast as a guest in their own genre.

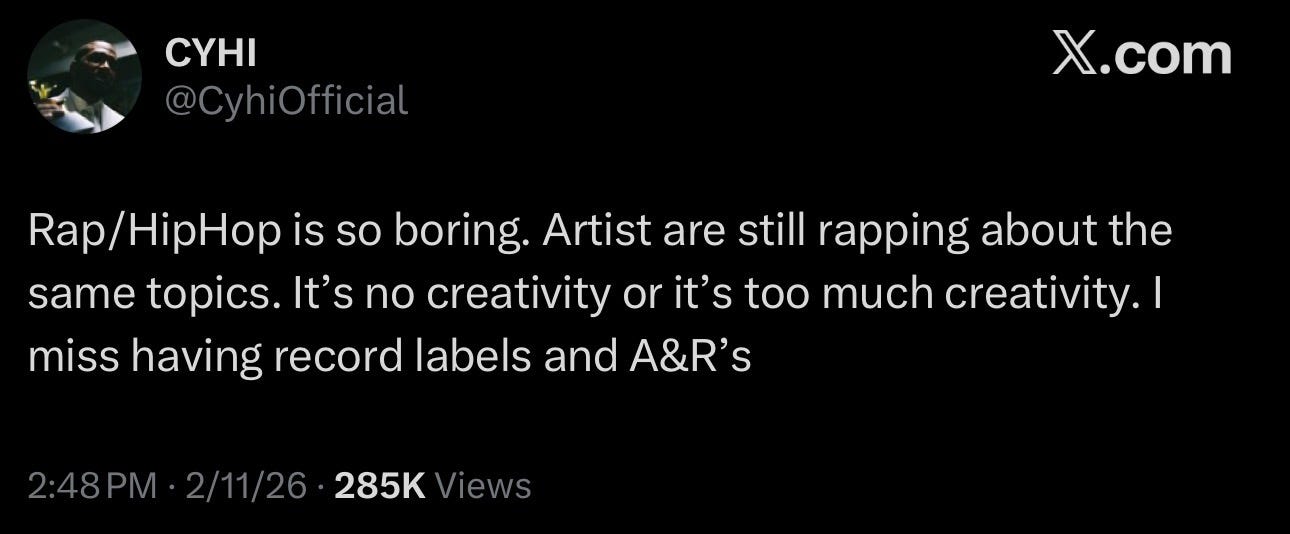

“Rap/HipHop is so boring. Artist are still rapping about the same topics. It’s no creativity or it’s too much creativity. I miss having record labels and A&R’s.” That sentence, posted on Twitter this past Wednesday by veteran rapper and songwriter CyHi, contains a contradiction so clean you could teach a logic class with it. Rap lacks creativity, or it has too much. The music is stale, or it is too unfamiliar. These cannot both be true. But they can both be felt by someone who misses a version of the genre that put him closer to the center, and CyHi, who spent more than a decade ghostwriting hooks and verses for Kanye West, Travis Scott, and a constellation of platinum-selling acts, has earned the right to feel displaced. Feeling displaced and diagnosing the problem correctly are different things, though, and the second tweet he fired off six minutes later pried the gap wide open.

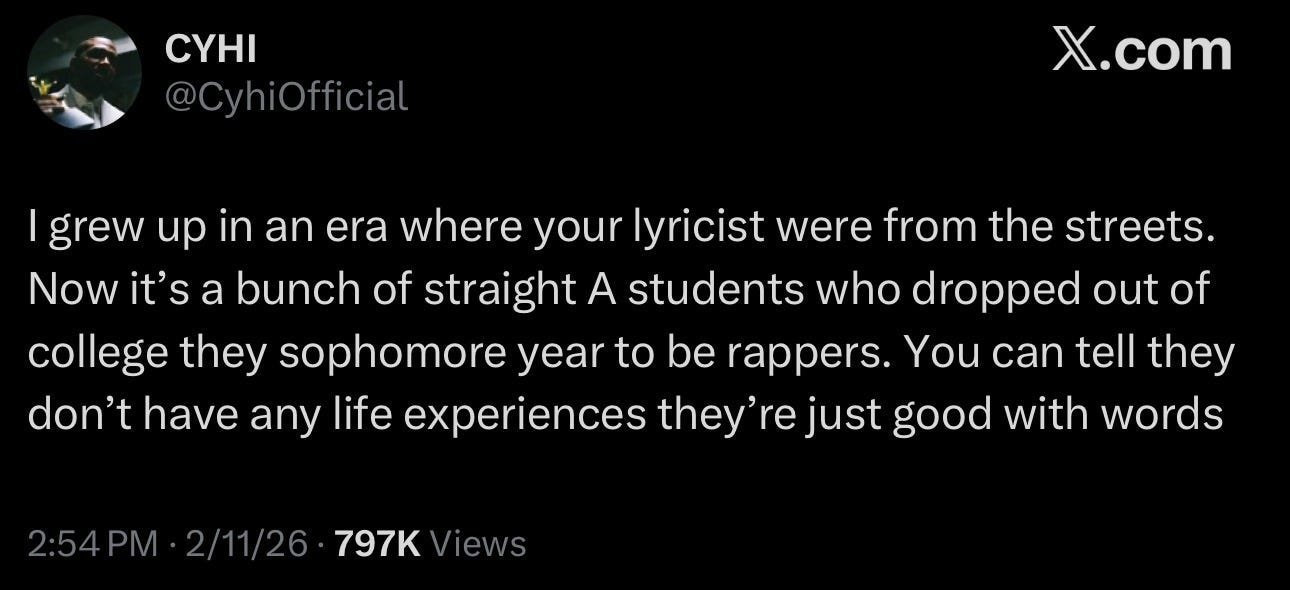

“I grew up in an era where your lyricist were from the streets,” he wrote. “Now it’s a bunch of straight A students who dropped out of college they sophomore year to be rappers. You can tell they don’t have any life experiences they’re just good with words.” Seven hundred ninety-seven thousand people viewed that one. The phrase “life experiences” is doing enormous labor in the sentence, and it deserves to be pulled apart before it hardens into common sense. CyHi is drawing a border. Rappers whose biographies pass a specific credentialing test land on one side, people who grew up adjacent to or inside of street economies, who carry scars that register as legible to a particular ear. Everybody else gets filed on the other, rebranded as tourists. Good with words, sure. Talented, maybe. But counterfeit where it counts, because their transcripts were too clean and their childhoods too cushioned to generate the raw material that makes rap feel like rap.

Born Cydel Charles Young in Stone Mountain, Georgia, raised Baptist by strict parents who barred hip-hop from the house until he was twelve, CyHi carries a Grammy-nominated songwriting résumé thick enough to paper a hallway. His solo material ranges from his Royal Flush series to Black Hystori to his long-awaited debut record, No Dope on Sundays. He holds credits on nearly every track from Kanye West’s Yeezus, contributed to My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and The Life of Pablo, co-wrote Travis Scott’s “Sicko Mode,” and penned songs across the Vultures sessions as recently as 2024. In 2021, he survived an assassination attempt on an Atlanta highway, his car flipped and shot up and left wrapped around a tree. None of this is trivia. CyHi has paid real costs, inside and outside the booth, and those costs give weight to his frustration. Weight and precision are different currencies, though, and his tweets buckle under the load of their own assumptions.

Start with the gate itself. “Life experiences,” as CyHi uses the phrase, narrows to a very particular slice of Black American biography. Proximity to drug economies, violence, incarceration, the daily friction of living without a safety net. These are real conditions that produce real art. Nobody with any sense disputes that. The trouble arrives when that slice becomes the only biography that qualifies a rapper to be taken seriously, because at that point rap stops functioning as a creative field and starts running like a passport office. You need the right paperwork. The stamp has to come from the right ZIP code, the right set of traumas, the right relationship to the criminal justice system. Anyone whose suffering took a different shape—debt, caretaking for sick parents, navigating a campus where they were one of seven Black students in the department, grinding a warehouse night shift to keep an apartment they could barely afford—gets filed under “just good with words.” Their life, under this frame, does not count as life.

Hip-hop has always had writers who arrived through different doors, including writers who came from rough neighborhoods and still went to college, still read books, still carried report cards home. Kanye West, CyHi’s own primary employer and champion for over a decade, built an entire mythology around being the college dropout in a room full of street rappers. OutKast came out of Atlanta’s Eastside and Southwest, attended the same performing arts magnet school, and spent two decades bending the music past anything “street” or “college” could contain. CyHi himself listed JAY-Z, Nas, T.I., OutKast, Jadakiss, Trick Daddy, and Juvenile as his favorites in a follow-up tweet. That roster includes men who sold drugs and men who earned degrees, men who grew up in Marcy Projects and men who grew up in Queensbridge, men whose streets looked nothing alike. The category “street” already stretches past its own borders if you take CyHi’s own pantheon seriously.

Benny the Butcher ran a nearly identical argument in October 2025, ranting on Instagram Live that “weird Twitter nerds” had snatched the culture from the streets. The grievance traveled well in certain corners. It mapped onto a real anxiety, that the people who decide which rappers get playlisted, which albums get reviewed favorably, which artists get booked at festivals, are increasingly people who never had to worry about making rent on the first. But the grievance also dodged the question underneath itself. If “the streets” once controlled hip-hop, who inside that arrangement decided which street stories got funded? Who picked which version of Blackness was presentable enough to sell a million records? The answer, every single time, was a label executive, an A&R, a white-owned distribution company, a radio programmer. Exactly the apparatus CyHi is nostalgic for.

That longing is worth pressing on. “I miss having record labels and A&R’s” reads like a sentence about quality control, and there is a version of that desire that makes sense. Someone who listens to two hundred demos and picks the ten that can carry an album. A professional who tells a young artist to rewrite a second verse, who invests in development instead of throwing content at an algorithm and praying. CyHi is old enough to remember when that filtering existed, and he benefited from it directly; West’s recording camps, which functioned like songwriting boot camps, are exactly the kind of intensive A&R environment that barely exists anymore.

But the wistfulness skips over what that filtering actually filtered. Labels in the ‘90s and 2000s did not simply improve quality. They bankrolled stereotypes that were legible to money. They pushed forward a very specific kind of “street” narrative, one scrubbed clean enough for suburban consumption, violent enough to titillate, Black enough to authenticate the product without threatening the buyer. Nuance got sanded off. Artists who could write about their block and their bookshelf in the same verse got steered toward the block, because the block sold. What CyHi remembers as curation was also a sorting mechanism that shrank the range of Black life that rap was permitted to depict.

The present is no less coercive; it just distributes the coercion differently. Playlist pipelines prioritize engagement metrics over craft, and platform incentives push artists toward provocation and brevity. Clip culture squeezes a three-minute song down to its most extractable fifteen seconds. Outrage reply chains generate more impressions than patient criticism, and stan warfare—the organized, quasi-political mobilization of fan bases to inflate or destroy an artist’s reputation—has replaced the old-school A&R phone call as the primary mechanism of gatekeeping. The gates did not disappear. They multiplied, shrank, and scattered across a thousand feeds.

Within hours of the “straight A students” post, large portions of the reaction calcified into a guessing game about which specific rapper CyHi was targeting. The internet assigned suspects, cross-referenced perceived slights, and treated the whole thread as veiled ammunition in somebody else’s beef. Whether he was dissing anyone in particular is beside the point, and answering that question only services the machinery that prevents hip-hop from holding a structural conversation for longer than ten minutes. The reflex to collapse every opinion into a proxy war between fan camps is a symptom of the same malady CyHi claims to be diagnosing. A culture so fragmented and so addicted to conflict that nobody can sit with an argument long enough to decide whether it holds up.

A later tweet attempted to narrow the claim, insisting he wanted “more street rappers be lyrical” and that he did not believe “just extreme street rap or extreme College rap is all hip hop has to offer.” Fair enough. But even the narrowed version still pressures rap toward a binary that has never accurately described who makes the music. “Street” and “college” are caricatures, and between them lies the actual territory where most people in this country live. Working, borrowing, repaying, arguing with landlords, driving kids to school before a shift, trying to write at two in the morning with the lights off because the electric bill is overdue. That catalog of daily pressure counts as life no less than a corner or a trap house or a cell block. Rap has room for all of it, and always has. Slick Rick spun fairy tales. De La Soul sampled Steely Dan. Biz Markie crooned about a girl who broke his heart at a party. Hip-hop’s earliest commercial era included party-starters and college-educated poets and comedians alongside hustlers and brawlers. The supposed golden age was already more varied than the wistfulness permits.

When CyHi says “you can tell they don’t have any life experiences,” he is making an aesthetic judgment and disguising it as a biographical one. He can hear that something is missing from certain rappers’ music, a grain, a tension, a specific gravity, and he attributes that absence to their résumé instead of to their writing. The error is serious, because it immunizes street-identified artists from the same scrutiny. If background alone certifies quality, then a rapper with the right credentials can coast on cliché indefinitely, and plenty do. Topic repetition is a craft problem that cuts across every background in the music. The boredom CyHi is reacting to is real, but its origins are structural—algorithmic incentives, collapsed attention spans, a distribution model that prizes volume over labor—not autobiographical. Blaming the “straight A students” locates the sickness in the wrong body.

What happens when one personal history becomes the only accepted visa into mainstream credibility is that the field stops expanding. Artists who might otherwise bring unfamiliar textures into hip-hop learn to perform a background they do not have, because that performance is the price of admission. Artists who genuinely lived through the conditions CyHi valorizes, meanwhile, watch their stories get flattened into branding. “Street” shrinks to a marketing tag, a shorthand for danger and scarcity that can be printed on a hoodie and sold at Coachella. The range contracts from both ends. And the culture that once housed Ms. Lauryn Hill and Scarface and Missy Elliott and Ghostface and A Tribe Called Quest and Three 6 Mafia in the same decade starts operating like a border checkpoint, stamping some passports and turning others away.

Nobody disputes that CyHi is a talented, accomplished writer who has shaped records that millions of people carry in their pockets. His displeasure about the current state of rap circulates widely among working artists, and not all of it is misplaced. Wanting more lyricism from rappers with street backgrounds is a reasonable ask. Wanting stronger A&R infrastructure and more developed artist pipelines is a reasonable ask. But packaging those desires inside a frame that treats education as a disqualifier and “good with words” as an insult, a frame that swaps craft standards for background checks, only tightens the belt on a genre that needs a longer runway. If CyHi and the growing chorus of artists who share his displeasure—Benny the Butcher among them—believe rap deserves better, they have the pen game and the industry knowledge to demonstrate what better looks like. Write the records. Fund the writers’ rooms. Mentor the artists whose résumés do not fit the template. The grievance, at this point, is on file. The work is what will shift the weight.